Popping two motors into a car is not only complicated, it doesn’t always end well.

Donn Anderson recalls early attempts, including John Cooper’s ill-fated original Twini Mini built 58 years ago

For a boost in performance, better traction, and perhaps improved handling to some, two motors seems an obvious solution. It would also eliminate the need to develop a larger engine replacement from scratch, but would that outweigh the not inconsiderable technical difficulties?

The idea of using a pair of engines dates back at least 86 years to the Alfa Romeo Bimotor single-seater racing car that was officially timed at 335km/h, or 208mph. Taking a lengthened Alfa P3 chassis, the Italians fitted two supercharged straight-eight 2.9-litre and 3.2-litre engines, one in front of the cockpit and the other behind the cockpit.

Both engines sent power to a mid-mounted differential with twin driveshafts then turning only the rear wheels. It avoided the complication of driving the steering wheels but it missed out on the four-wheel drive or traction benefits, and the car was said to be a beast to drive — thirsty, with a habit of eating tyres. Little wonder Alfa only made one example. The 1935 racer rests quietly in a museum today.

The world’s first dual-engine 4WD car to go into production was a limited run of Citroen 2CV Safari models launched in 1958. Intended for farmers and as a workhorse in French North African colonies, the Safari still accommodated four passengers and had a boot-mounted engine driving the rear wheels supplementing the identical front-located 425cc twin-cylinder, air-cooled motor powering the front wheels.

Both engines operated totally independently, and there were two fuel tanks, one underneath the driver’s seat. The small Citroen had uprated suspension, a strengthened chassis, single clutch and a floor-mounted gear lever linking the two engines, and larger carburettors to help overcome the modest power. Using the conventional front-drive setup, the 2CV had a top speed of 56km/h, increasing to 100km/h when both motors were in use. And, of course, if one motor failed, the 2CV would still operate — handy if you were stuck out in the desert.

Drum brakes were mounted inboard to reduce water and mud intrusion, and the dampers were horizontally positioned instead of vertically to limit damage from obstacles. The four-speed manual gearbox was linked by a single clutch pedal. Owners liked the idea that the Sahara could be powered by both engines for maximum traction or by either the front or rear engine for improved fuel economy.

Citroen made the Sahara for a short period, with a lone final example built i 1971. Of the 694 produced, only around 30 are still running , and they are seriously prized. A ‘barn find’ example sold in Paris in 2016 for a record price of NZ$283,000. The 2CV Safari was extremely competent in snow or rough desert territory, but was needlessly complicated and a convoluted way to add two more driven wheels.

Yet others could see merit in dual power units, and the idea caught the attention of Mini designer Alec Issigonis, and George Harriman, the chairman of the British Motor Corporation. In spite of difficulties synchronising both engine and gear changes, in 1963 the two BMC executives conceived a military version of the Mini Moke using two 1.1-litre A-Series engines. The rear engine was located behind the second row of seats using the existing sub-frame to mount it. With its impressive 120km/h top speed, the prototype Moke seemed to have good potential, but after trialling the open vehicle the US Army failed to place an order due to worries about the lack of ground clearance on the small 10-inch diameter wheels.

THEN THERE WAS THE TWINI-MINI

Meanwhile, with encouragement from Australian world champion driver Jack Brabham and a young New Zealander called Bruce McLaren, John Cooper was inspired to turn the standard Mini into a pocket rocket. And so the Mini Cooper arrived in September 1961, two years after the launch of the original 848cc Mini.

Short body overhang, a wide track, a low centre of gravity, low weight, and front drive soon made the Mini a sporting favourite. Yet John Cooper thought there might be more potential and, on a visit to the Austin plant at Longbridge in 1964, he drove the experimental four-wheel-drive Mini Moke with an engine at either end. Two engines instead of one seems like a good idea until something goes wrong, a message that proved painfully true for Mr Cooper.

He raced back to his garage in southwest London with a vision of popping a motor into the back of a Mini where the rear seat is usually located. Over the next six weeks, Cooper became obsessed with the project, with parts scattered across the workshop.

However, apparently, Cooper was not the first to try two engines in a Mini. British race car builder Paul Emery had run a front-driven Formula 3 open wheeler and in 1962 adapted a Mini to accommodate two power units. However, he had gear linkage problems and abandoned the project, saying the car had good traction — “But that’s about all,” said Emery, the man who likely put together the first Twini Mini.

Undeterred, Cooper was deadly serious about his Mini. The front power train was a 1,088cc Group 3 Formula Junior pushrod engine with twin SU carburettors developing 82bhp, while the rear motor was also an Austin/Morris A-Series unit, bored out to 1,212cc and turning out 96hp. So that meant the Twini Mini developed 178bhp, or a similar power-to-weight ratio as a Ferrari Berlinetta.

Steel channel sections under the doors and reinforced sub-frames gave extra torsional strength, and there were two gearboxes with matching ratios, and a pair of closely mounted and linked gear levers. The levers were linked by a sliding rod to allow synchronised changes. Years later Cooper said, “The steering arms were bolted to the rear sub-frame and virtually became another wishbone.” He did not envisage problems synchronising the two ends “since nature acted as a differential”.

There was a problem of time lag between the front and rear carburettor openings, solved by a solid link between the carbs. Venting fumes from the rear engine was a challenge, while noise levels were understandably high.

PLANS FOR LIMITED RUN OF TWINI MINIS

Not only did the car have two ignition switches, but there were also two fuel pumps, two oil pressure gauges and, of course, two rev counters. An excited Cooper wanted the British Motor Corporation to make 1,000 Twini Minis so the model could be homologated for motorsport.

The Mini was great in the snow and gravel and had possibilities as a formidable rally car. A problem arose when one of the engines went off-song, dramatically changing the handling. Sir John Whitmore, a famed champion Mini racer, tested the prototype at Brand Hatch, finding the car neutral through corners provided both engines were in tune.

Full steam ahead, then. John drove the mighty Mini whenever he could and, in May 1964 was heading south on a dual carriageway highway to Surrey, where he was to dine with racing driver Roy Salvadori. Something went wrong, and the car rolled several times. Cooper suffered cracked ribs, amnesia, and severe concussion. The crash almost cost him his life.

The car was so badly wrecked it was impossible to find the cause, but a front engine malfunction, a seized rear engine, or a jammed gearbox were cited as likely failures. John Cooper thought the ball joint in one of the steering arms had seized, but the accident abruptly killed off the Twini project.

Several replicas have been made, and the one built in 2002 in Jay Leno’s remarkable collection is a newer generation BMW Mini R50 with two of the standard 1.6-litre, single overhead Chrysler Tritec engines. The newer technology made it an easier conversion than the original classic Mini, with shifting by cable instead of mechanical linkages.

Several Twini Mini replicas have differing layouts. One has a modified boot to accept the rear engine turned around and mounted backwards. Positioning is critical as the driveshafts have to sit relative to the wheels and everything else. This replica uses the standard interconnected Hydrolastic suspension, unlike the John Cooper car with its older-design rubber cone independent suspension. It also boasts a single ignition key with both ignition systems live.

Downton Engineering in England produced some brilliant competition Minis and also put together a Twini with a pair of 998cc engines. This car ran in the 1963 Targa Florio but had numerous problems with overheating and gear changes that sometimes failed to synchronise. Cooling for the rear engine was often troublesome and some of the replicas have tried different mechanical layouts, including a shaft linkage.

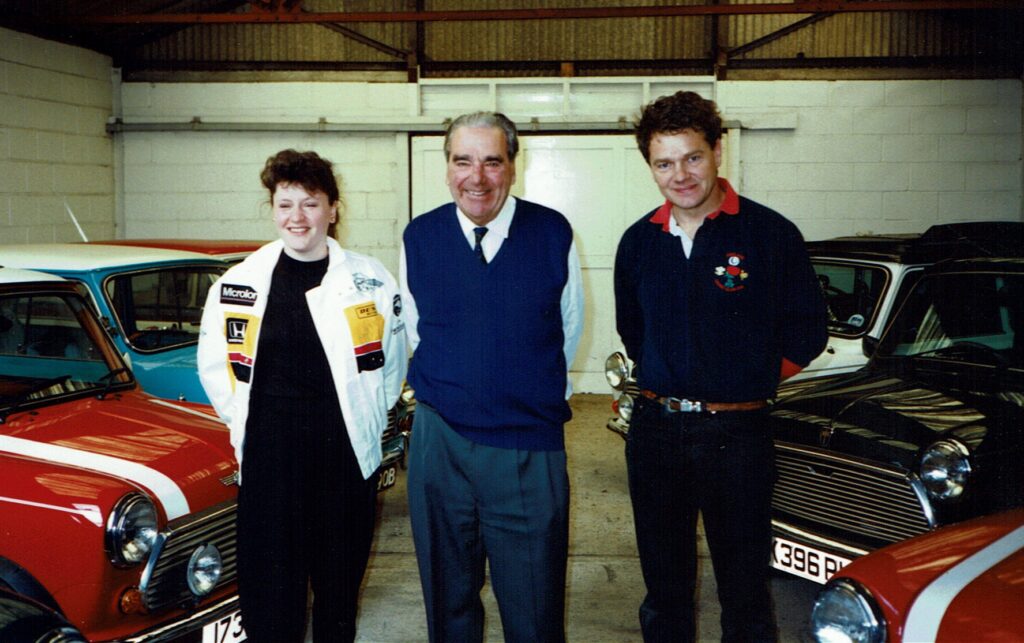

While the John Cooper Twini no longer exists, the original two-engined Moke has been preserved. Twenty-nine years after the Twini project was abandoned, I was with Bruce McLaren’s daughter Amanda at the Cooper family’s garage in West Sussex where John and his son Michael showed us around a stunning array of classic Mini Coopers — all simply front-driven with a single engine.

The twin-engine Mini philosophy from the sixties failed, yet it did not mark the end of trying power at both ends. In 2005 Jeep built the Hurricane concept with two 5.7-litre 330bhp semi V8s that provided so much traction the vehicle could spin 360 degrees on a sealed surface like a crab turning. The Saab 93 Monstret in 1959 had two three-cylinder, two-stroke engines, both located up front, but handled poorly at speed and the factory only made one example.

NEW PLYMOUTH MORRIS 1300

Retired New Plymouth mechanic Albert Gordge spent more than four years converting a 1972 Morris 1300 into a twin-engined, four-wheel drive car, making a new rear sub-chassis for the rear engine sourced from another 1300. To make way for the rear A-series BMC motor, the original petrol tank was removed, and a new 38-litre tank was installed in the back seat to feed both motors.

Albert spent much of his time lying on his back on his garage creeper, working beneath the car, and it took him a month just to sort the two gear linkages. The Morris, which runs well, has no vibration, is completely legal and certified, boasts a combined clutch, and has two keys and two chokes. A one-time stock car champion, Gordge said the Morris, which retains its Hydrolastic interconnected suspension, was an engineering exercise and a challenge.

Nobuhiro “Monster” Tajima, who turns 72 next month, caused a stir in 1995 with his wild twin-engined Suzuki Escudo (an early Vitara) rally car that employed a pair of turbocharged motors, two multi-plate clutches, and two straight-cut, transversely mounted gearboxes. An electromagnetic-controlled disc clutch centre differential drives two limited slip differentials to all four wheels. The Japanese driver became a hillclimb legend in New Zealand, regularly winning the annual Race to the Sky hillclimb near Queenstown.

SUPERCHARGED LANCIA TREVI TWINI

To help develop a four-wheel drive system for Lancia rally cars, the Trevi Bimotore saloon in 1984 had a supercharged four-cylinder engine driving the front wheels and a second front sub-frame placed in the rear, complete with another engine and gearbox. It had two gearboxes linked mechanically and the engines used a drive-by-wire system, delaying power to the rear axle to reduce oversteer. The Trevi’s rear doors were welded up and extra cooling was required for the rear engine, but while fast the overweight Lancia still had overheating dramas.

In Florida, Warren Mosler began offering his modified Cadillac Eldorado TwinStar with a pair of front and mid-mounted Northstar V8s. The Mosler had a shared throttle linkage, and the two engines worked independently of each other, with two transmissions shifting at different times. The Cadillac’s wheelbase was extended so the full regular interior dimensions and trim could be maintained.

Two Spanish brothers created the Seat Ibiza Bimotor in 1986, joining two front sections of the car together, hidden under the bodywork, and the car was successful in rallying. In 1987 Volkswagen built a special Golf for the Pikes Peak hillclimb in the US. The VW had an aluminium monocoque with Kevlar body and two modified 1.8-litre turbo GTi engines, but was too heavy and had insufficient power. Created by German Roland Mayer, the Audi TT Bimoto of 2007 had its second 1.8 turbocharged motor where the rear seat was usually positioned.

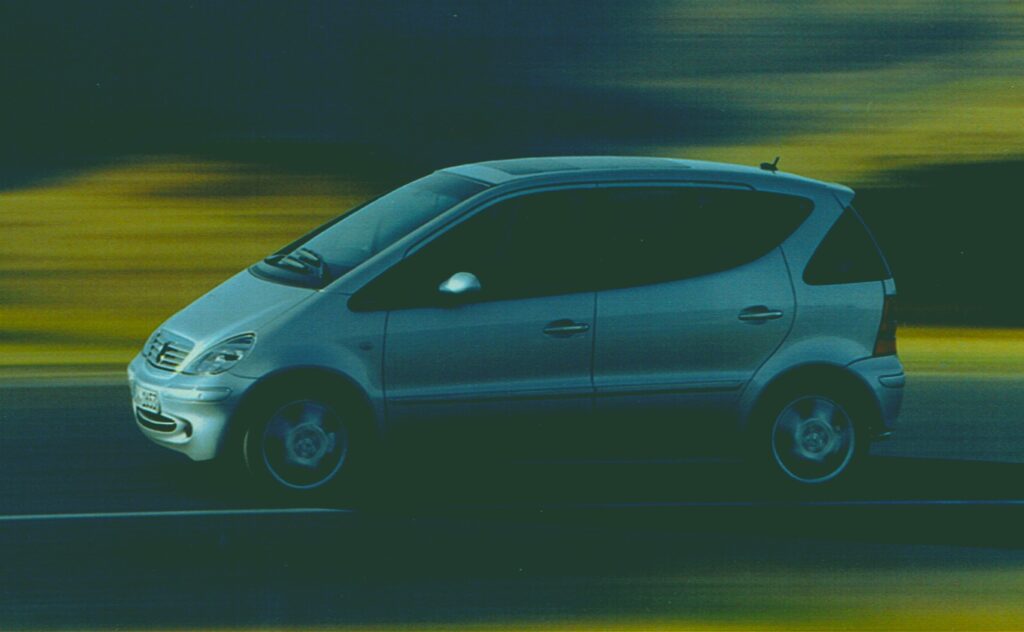

Mercedes added an engine underneath the boot floor of the small ‘A’ Class, taking advantage of the car’s sandwich floor design. The second engine slotted neatly between the rear wheels so the hatchback still had boot space. An automatic clutch synchronised the two engines electronically, and the 1.9-litre engine powering the rear axle could be switched off to revert to front drive. One of the four made by Mercedes was gifted to Mika Hakkinen after he won the 1998 Formula 1 championship in a McLaren-Mercedes.

Mechanical complexity and costs outweigh the traction benefits and reduction in payload area, so historically, ‘twinis’ made no sense as a drivetrain for production cars, but times are, of course, changing. Electric motors have altered and simplified the implementation of multi-power units, and modern metal like Tesla and Porsche Taycan have 4WD with separate drive units which means today ‘twinis’ are alive and well. Some designs have also been touted with fully independent power units attached to each of the four wheels, which can also turn through 360 degrees, giving the vehicle unrivalled manoeuvrability.