Donn Anderson recalls waiting patiently 60 years ago to take a photo of a famous racing driver — and he wasn’t disappointed

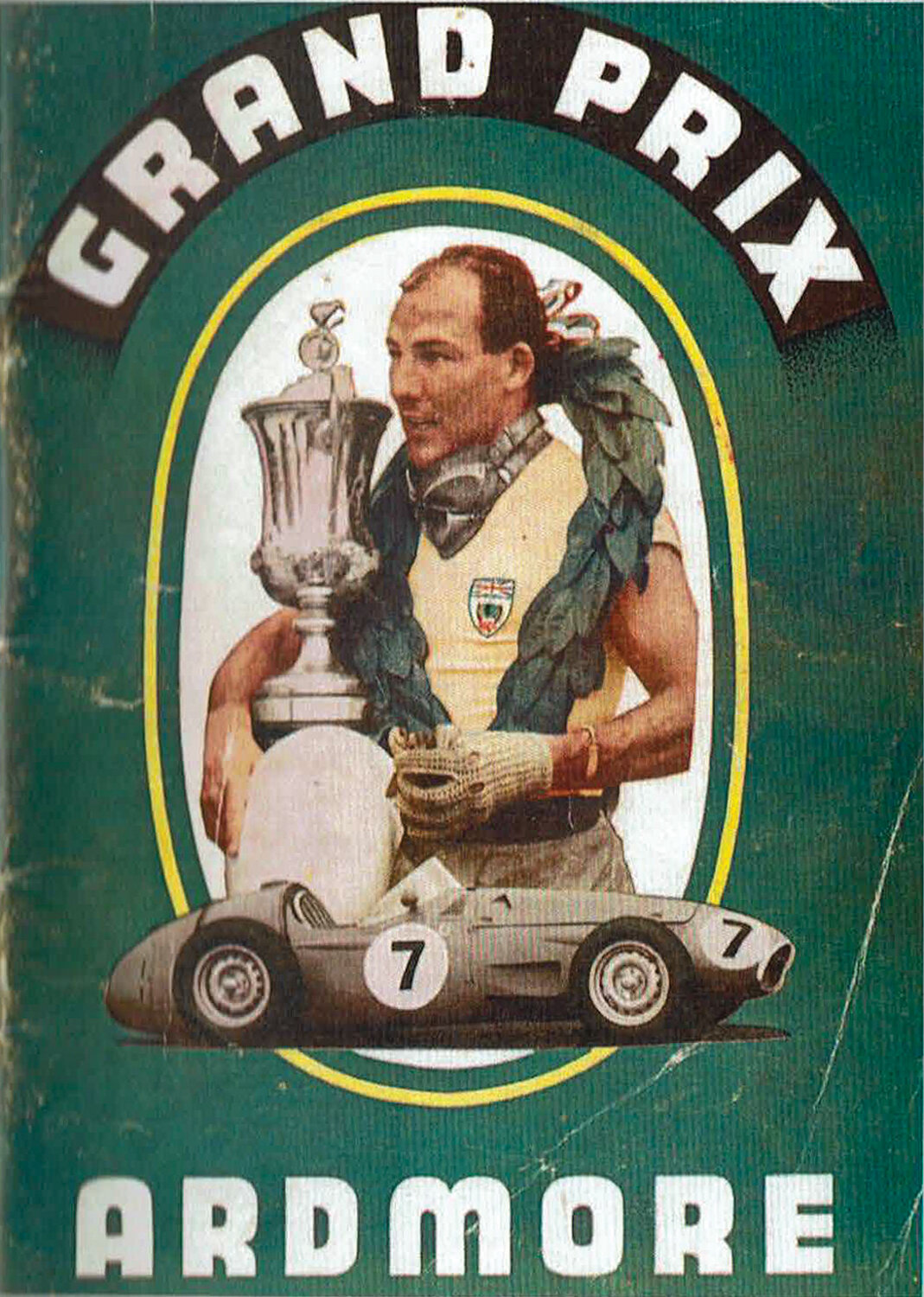

Stirling and the Maserati 250F graced the cover of the 1957 NZGP programme, although the great master was absent that year

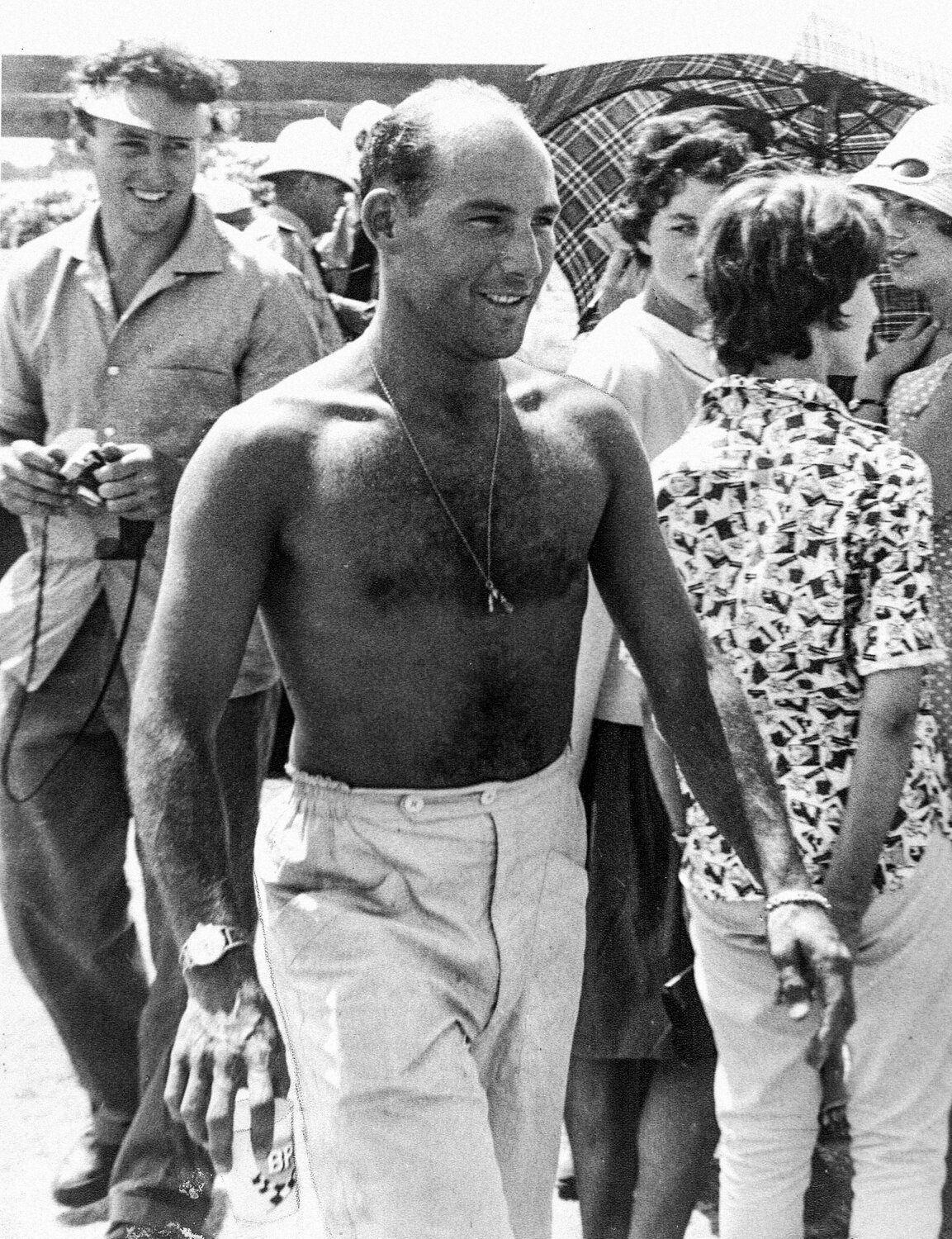

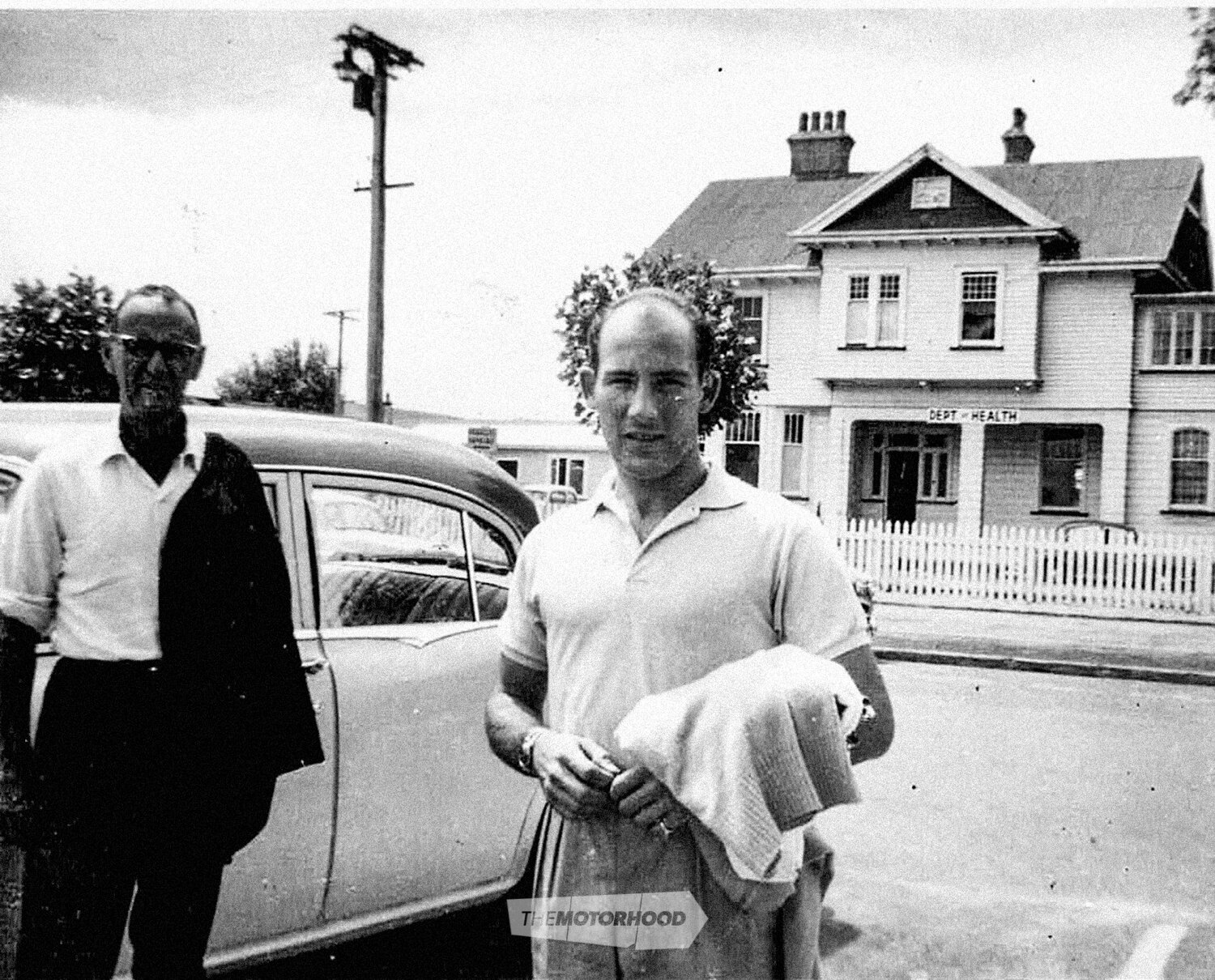

Standing on the pavement outside the old DeBretts Hotel in Rotorua on a warm January day 60 years ago, a relatively shy 13-year-old boy waited, box Brownie camera in hand, for a legendary Englishman to arrive from a leisurely swim — hotel reception had confirmed that Stirling Moss would return in a few minutes. When he did, he was happy to pause while the young lad took his photo, brushing aside agitated comments from his minder to the contrary.

Putting together a schoolboy motoring magazine gave me no sense of entitlement, but Moss was more than willing to interrupt his leisure for an unimportant photo opportunity that would have had zero consequences for his career. Stirling is that sort of chap.

The year before, I had written to him at his London address and promptly received a welcoming reply from the late Ken Gregory, who enjoyed a 16-year partnership managing Moss. Gregory apologetically explained that Moss was out of the country racing and could not immediately answer my letter — but he extended best wishes for my budding publishing venture. At the time, Stirling was receiving more than 10,000 letters a year from fans young and old, and he said he felt that if people bothered to write to him for an autograph or photo then they should get one — if possible, by return of post. My first-time occasion with the great man was clearly nothing if not normal.

Three or four days after my brief Rotorua meeting, Moss was at Ardmore smashing records and winning the sixth local Grand Prix (GP) in the Rob Walker Cooper Climax.

Stirling Moss, the greatest racing driver never to win the Formula 1 (F1) World Championship, will be 90 years old this September. The five-time visitor to New Zealand never looked like slowing down until he suffered a chest infection while on holiday in Singapore in 2016. After 134 days in hospital, the slow recovery prompted Moss finally to retire from public life early last year.

Injuries and illness are nothing new for the Englishman. Driving an offset-cockpit HWM Alta in the 1950 Formula 2 Naples GP, Moss was about to take the lead when his car was hit by a backmarker who had lost control.

“I was catapulted off and hit a tree, breaking my kneecap on the bottom of the dash and knocking out my front teeth on the top of it,” said Stirling.

Back in London, Moss’ father put his dentistry skills to use, fitting false front teeth to the young Stirling, which he still has today.

In Argentina for the GP in 1958, Moss was horsing around with his first wife Katie when she accidentally poked him in an eye, taking 4mm off the cornea, forcing him to race with a patch over the painful injury. Against all odds, and with an underpowered car compared with the opposition, Moss fought his way to victory that day — the first World Championship success for a Cooper and the first to be won by a private entrant.

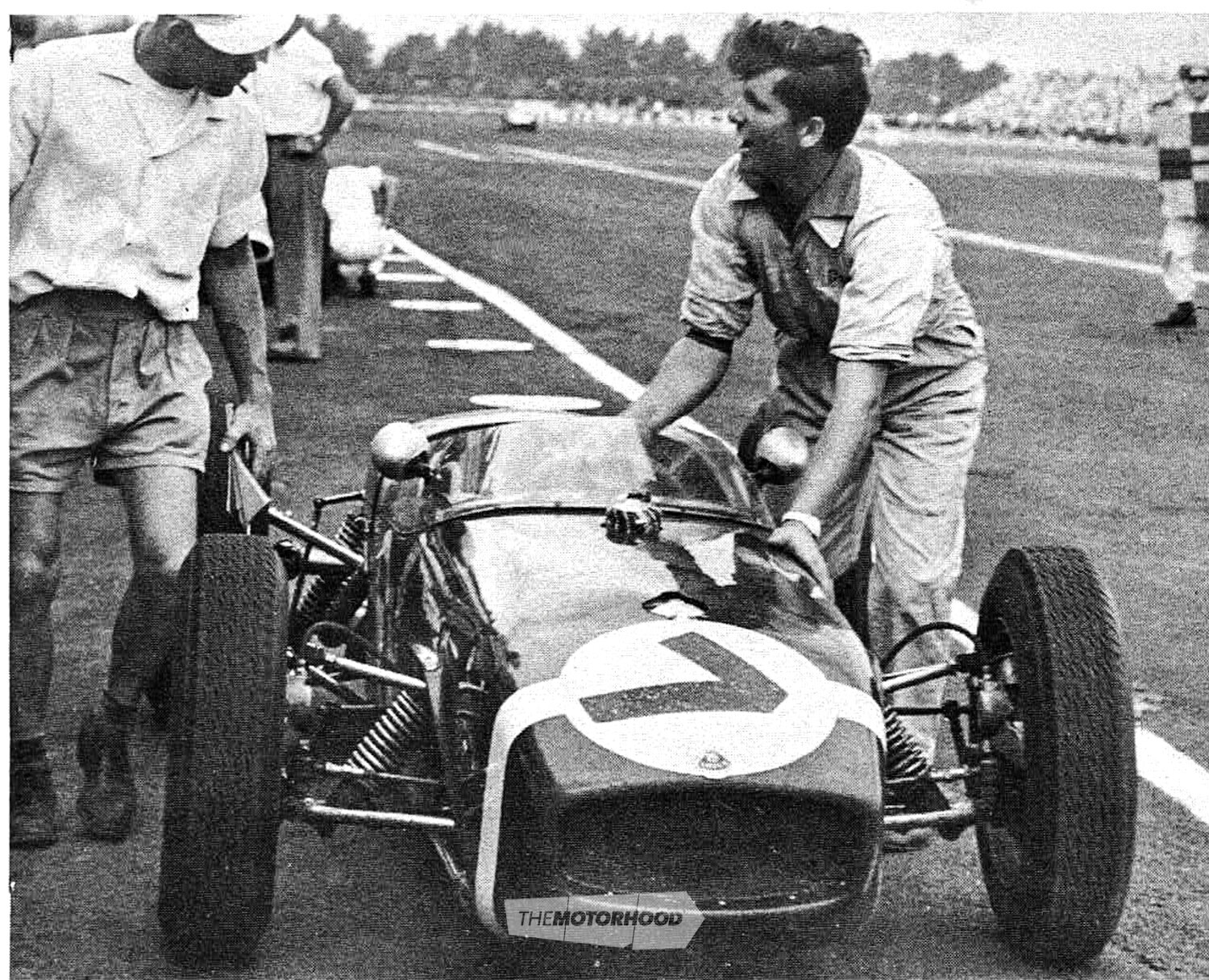

A mechanic pushes the stranded Moss Lotus into the Ardmore pits. Stirling had been leading the 1961 NZGP in the Rob Walker car when the transmission failed

Seemingly indestructible

Stirling is seemingly indestructible. He survived two appalling accidents — at Spa in 1960 for the Belgian GP and then on Easter Monday at Goodwood in 1962. Even his home has proved dangerous for him in semi-retirement. His long-time Mayfair flat in London is packed with gadgets, including probably the only carbon-fibre lift in the world, built by mechanics of the Williams F1 team. However, the gadgets do not always work as they should.

In 2010, Moss fell three floors down the lift shaft in his flat when the lift door opened and the lift was still one floor higher. As the door opened, Moss put one foot into the empty space and fell, breaking both ankles and suffering other injuries in the horrific accident. His daughter, who was with him, peered into the darkness below and thought he was dead.

“If they took an X-ray of my whole body, with all its plates, pins, and Rawlplugs, it would look like something from an art collection,” he later quipped.

Yet the master has never lost his love of cars. Just five days after the lift accident, Moss asked a friend to bid US$1.7M for a 1962 Porsche RS11 Spyder at a Florida auction to give him “something to look forward to when he recovered”. By the late ’90s, Stirling owned an interesting collection of cars, including a Lola sports racing car, a Lotus 23, an Elva-BMW, a Shelby Mustang, and an Alfa Romeo TZ1.

At the Brooklands Museum in 1998, Moss enthusiastically inspected the MG EX 181 in which he had set a record-breaking 254.91mph (410.23kph) at the Bonneville Salt Flats 41 years earlier. The mid-engined EX 181 was fitted with a 1.5-litre BMC B-Series engine modified with twin-overhead camshaft, unlike the production pushrod motor, and a Shorrock supercharger that elevated power output to 290bhp (216kW) at 7300rpm. Running on small 15-inch diameter wheels,and sporting a single disc brake mounted inboard and acting on the rear wheels only, the experimental MG took almost 5km to slow down from its maximum speed.

Stirling remembered the record attempt as “possibly the most frightening experience that I have had”. He said that doing 290kph in the Vanwall F1 single-seater did not feel all that fast in comparison with doing the same speed in the enclosed cockpit of the MG, with its fully reclined driving position. Moss reasoned that it was not that the car was unstable or dangerous but its high sensitivity and the necessity to do everything with it so gently and delicately.

Writing in his 1961 book A Turn at the Wheel, Moss said, “You thought of what could go wrong — fire or total seizure, which might slant the thing sideways and then turn it over. You could not just bale out if trouble developed.”

It was an experience he was happy not to repeat.

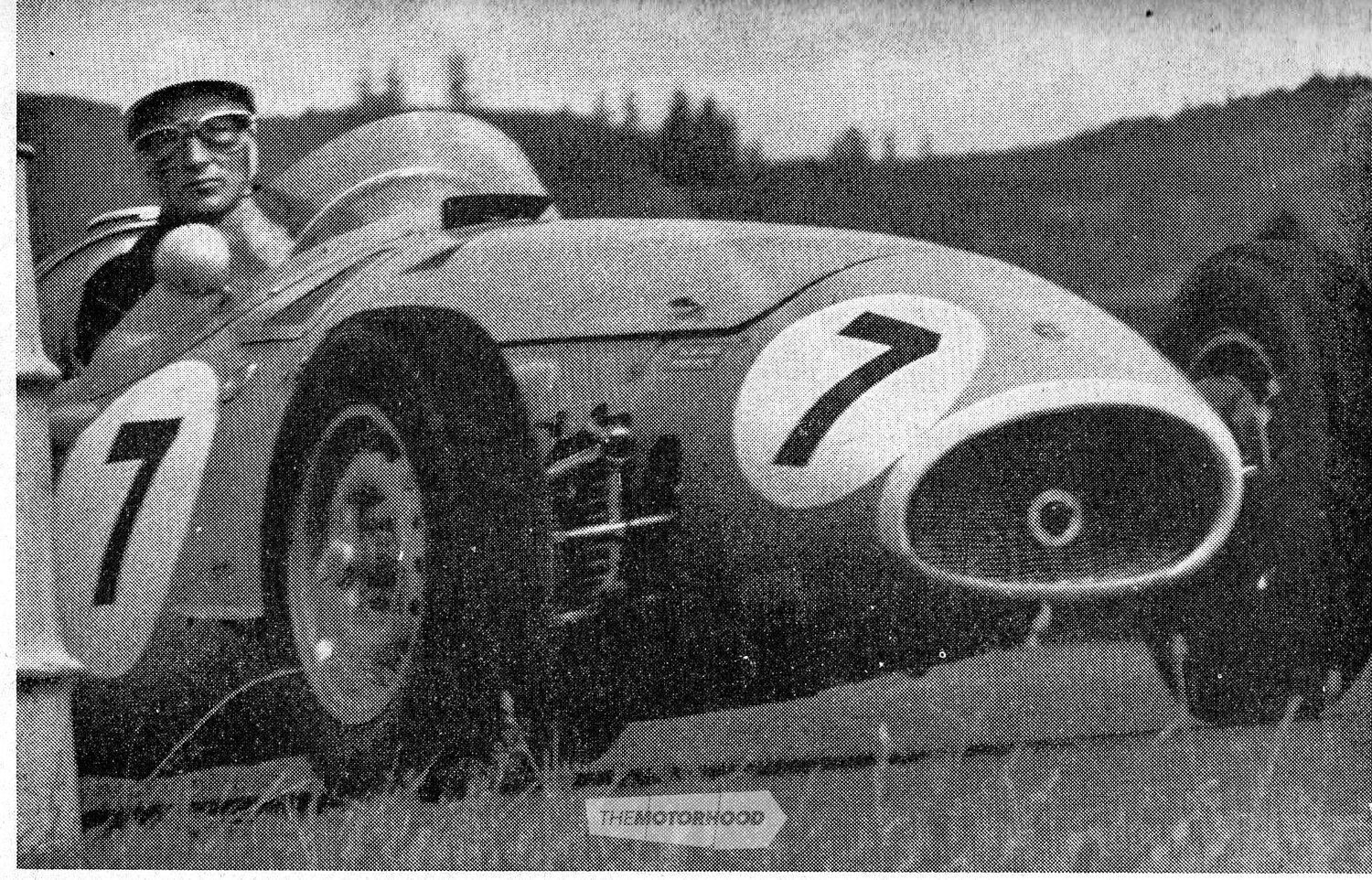

Moss in the Maserati 250F en route to victory in the 1956 NZGP at Ardmore

A fit and happy Stirling Moss in the pits for the 1962 Lady Wigram Trophy race at Wigram in Christchurch. He won the race in his Lotus 21 Climax (photo: Robin Curtis)

The New Zealand Grands Prix

As a 10-year-old, I had seen the master win the 1956 New Zealand Grand Prix (NZGP) in his Maserati 250F, a feat he repeated in a Cooper Climax on his next visit to our shores three years later. Then, in 1962, there was that simply amazing drive in the pouring rain when Moss outclassed the field to win the final GP to be held at Ardmore. Seventeen years later, at the age of 50, he was back to team up with Denny Hulme in a Volkswagen Golf GTI, finishing second in the 1979 Benson and Hedges production saloon event at Pukekohe.

Fast forward to 1987, and, in what was pretty much a low-key event for such a great man, Fleet Card flew him from London to man its stand at the 1987 Auckland Motor Show. How fortunate for me that the New Zealand Car magazine stand was right next door and, as editor of the publication, I had generous time to talk about the old days with the maestro. Few people chatting to him at that show would have realized that Stirling was the first to win his home country’s GP at Aintree in 1955, and was the victor in 16 F1 World Championship GP races between 1951 and 1966. Then, there was that brilliant 1961 Monaco GP, when, in an outclassed Lotus 18, he beat three of the all-conquering works Ferraris. While Moss never won the World Championship, he was, nonetheless, runner-up on four occasions and third a further three times.

Moss drove in 85 different classes, and won 212 of the 529 races that he entered. Perhaps his greatest success was winning the 1955 Mille Miglia for Mercedes, which he described as “the only race that really frightened me”. Stirling recalled that the fearsome eight-cylinder space-frame-chassised, alloy-bodied Mercedes 300 SLR that he mastered in that lengthy and gruelling Italian road race with navigator Denis Jenkinson was “the greatest racing car of all time and indescribably robust. The 300 SLR had perfect balance, and even when you had to brake harshly, it never lost directional stability and remained extremely precise to steer”. He is too modest to admit that this was maybe the most epic drive ever.

Brake-pedal failure

The actual Mercedes 300 SL Gullwing road car that Moss drove during preparation for the 1955 Mille Miglia was recommissioned after 30 years in storage and reappeared about 10 years ago with just 56,000 miles on the clock. A development of the 1951 300 SL racer, 1440 Gullwings were built by Mercedes between 1954 and 1957, and wealthy buyers could choose between five different rear-axle ratios.

Jenks and Moss teamed up again in a 4.5-litre Maserati for the 1957 Mille Miglia, running at speeds of up to 290kph on public roads within 3km of the Brescia start. Soon after, with an approaching corner, Stirling went for brakes only to find nothing there — the pedal had snapped with not even a stub.

“I just could not believe that the pedal had broken off — there was just a gap between the accelerator and the clutch,” he said.

Stirling Moss after winning the 1959 GP at Ardmore in a Cooper Climax, with a young Bruce McLaren and Jack Brabham on his right and a jovial Frank ‘Buzz’ Perkins in white shirt and tie to his left. Perkins was secretary of the New Zealand Grand Prix Association and a great promoter

It was then simply a matter of turning around and motoring slowly back to the start, where the Maserati mechanics were astonished to see Moss brandishing the brake pedal. For this pair of Englishmen, the Mille Miglia lasted less than four minutes and just 12km.

Driving his own Maserati 250F, Moss turned in the fastest lap during practice on a soaking-wet Circuit Bremgarten for the 1954 Swiss GP, amazing the Mercedes team with its superior cars. As a result, Mercedes signed him for the following year. Years later, he rated that practice lap as perhaps the best and most significant performance of his entire career.

In 1951, Enzo Ferrari himself phoned Stirling and asked if he would drive one of his cars in the Bari GP. Moss readily agreed and flew to the venue, where he saw his car in the Ferrari garage and climbed into the cockpit. A mechanic asked him what he was doing and when Moss replied, the Italian answered that the car was for Piero Taruffi. Ferrari had apparently changed his mind without bothering to tell Moss, so, unsurprisingly, a decade passed before Moss would contemplate joining the Italian team.

Moss was scheduled to drive for Ferrari in 1962, and Enzo even consented to painting the car Rob Walker blue or green with a Union Jack on the side and having it maintained in Britain. These plans came to a grinding halt following Stirling’s serious accident at Goodwood.

Keen traveller

A long-time keen traveller, Stirling favours Australia and the US, and also has fond memories of his New Zealand visits. On 2 January 1959, Katie and Stirling flew into Auckland from Los Angeles to be greeted at the airport by hundreds of people and given a tremendous reception.

Again writing in his 1961 book, he said, “The New Zealand public are fantastically enthusiastic and it was estimated that one in three of the Auckland population attended the race [the Ardmore GP]. People had camped out all night, and at 6am on race day the queues stretched for five miles. Our next few days were very full, as we were taken to see the sights as well as make personal appearances at cinemas and press conferences, at the request of the promoting club.”

Moss was delighted to see that the old Maserati 250F that had taken him to victory at Ardmore three years earlier was again doing well in the hands of local driver Ross Jensen. When a half-shaft failed in Stirling’s Cooper Climax during the preliminary race, chief rival Jack Brabham promptly offered a half-shaft from the spare Cooper that he had trackside.

“Jack’s gesture sums it up best: sportsmanship is helping out a competitor when you realize that by helping him out he has a very good chance of beating you,” said Stirling.

Indeed, Moss went on to win the NZGP from Brabham and Bruce McLaren.

The photo that a young Donn Anderson took with his box Brownie camera at Rotorua in 1959 on his first, nervous meeting with the great man

Sportsmanship

Stirling practised what he preached, as evidenced by the Portuguese GP incident in 1958 when he backed Mike Hawthorn’s statement to officials that he had pushed his stalled Ferrari on the pavement and not the track.

“Technically, the stewards were right in that he had committed a breach of the rules, but morally they were wrong,” said Stirling.

As a result, Hawthorn kept his second place and beat Moss to the World Championship title for the year by just one point.

“I backed Mike on a point of principle, and that it cost me the championship was one of life’s little ironies,” he said.

Badly injured when a wheel came off his Lotus during practice for the 1960 Belgian GP, Moss missed three races yet came back at the end of the season to win the US GP at Riverside. Then, on Easter Monday at Goodwood, a high-speed crash put him in a coma for a month and effectively ended his career. To this day, he has never found a definite, watertight reason for the accident.

Moss had almost superhuman abilities, and is surely the most outstanding British racing driver of them all — and certainly what a great racer should be. A true sportsman and a hero, he once said that a racing driver needs to speak the language of a car and get to know what it is saying. As one critic said, Moss drives a car with the delicacy of a surgeon.

Sometimes accused of being a car-breaker simply because of his pace even when comfortably leading a race, his philosophy was, “I would rather lose a race driving fast enough to win it, than win one driving slow enough to lose it.”

He has always been an Anglophile, and once said, “It’s better to lose honourably in a British car than win in a foreign one.”

England is his home, and he considers London the centre of the world. Moving into semi-retirement — although he is not a person who sits still for long — he invested in London property to provide an income. Compared with today, racing drivers earned miniscule sums in the ’50s and ’60s, when Moss was at his peak. In 1960, his annual income was equivalent to a mere $74K, leaving him just $16K after expenses and tax. As he said in later years, all he had to sell was his name or his time. Zipping about London on his motor scooter, he even squeezed in a garage opening on his wedding day to Susie.

The only time that Stirling has lent his name to a car was in June 2016, when Lister produced its Knobbly Stirling Moss, a replica of the 1958 Lister that is believed to be the only magnesium-bodied car in the world. Only 10 were built — each with a price tag of £1M — to celebrate the 60th anniversary of Lister’s first racing sports car.

Moss reckons that he probably had more mechanical failures than any other racing driver, including seven instances of wheels falling off, eight brake failures, two sheared steering columns, and too many suspension failures to remember. Apart from Mercedes — which seemed bullet-proof — he once said that every time he sat in a racing car there was a good chance some part of it would break.

Not for a moment would I expect Moss to remember me, but, as sure as day follows night, I would instantly recognize this man with a name that has long been a generic term for a racing driver. His mother wanted to name him Hamish, but he is thankful that his father came up with Stirling, which he thinks sounds so much better. When bumping into him while I checked into The Goodwood Hotel in 2008, he was as friendly as usual. Next morning, for the annual Festival of Speed, he appeared bright and chirpy with his third wife, Susie, proudly wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with the words: “Who do you think you are — Stirling Moss?”

In 2009, Moss celebrated his 80th birthday at Goodwood, where Lord March appropriately arranged three cars for him to drive: a Mercedes W196, a Lotus 18, and an Aston Martin DBR3. We will have to wait until this September to see what Stirling and the motor sport fraternity have in mind for his 90th.

Moss prepares to do a demonstration run in the famous British-built front-engined Vanwall F1 car

Stirling with the MG EX 181 record-breaking car at the Brooklands Museum in Surrey, England, 1998 — 41 years after he drove it on the Bonneville Salt Flats in the US in what was, he said, a frightening experience