data-animation-override>

“Published in New Zealand Classic Car Issue No. 181”

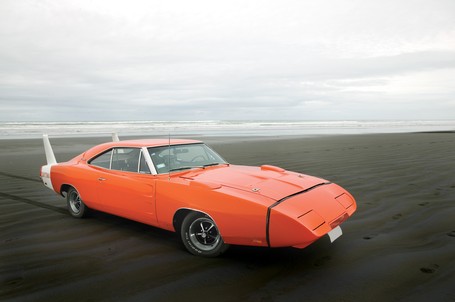

Any Daytona is a special car in its own right, but this EV2 Hemi Orange car has its own unique chapter in the Daytona history pages.

Words: Bruce Simpson Photos: Jared Clark

Motor sport had enjoyed phenomenal growth in the United States, driven by the burgeoning baby boomers’ insatiable desire for speed. NASCAR, ruled with an ironclad grip by founder Bill France, ran on the dirt tracks, which were circle tracks, and its organisers were busy constructing more high banked super-speedways fuelled by ever increasing television coverage that had dramatically enlarged the stock car fan base from its Dixieland home, with nationwide coverage boosting popularity of what was just once a good ol’ boys affair. GM had pulled its divisions out of sanctioned motor sport in 1963, leaving Ford and Chrysler locked in a deadly battle for supremacy.

Win at all costs

The hoary old dictum, ‘win on Sunday, sell on Monday’, took on a whole new meaning — victory at the premier Grand National race, the Daytona 500 brought hordes of eager punters onto showroom floors seeking a piece of the action. Even though ma mightn’t let pa go the whole hog, and option the hottest big-block V8s, happy buyers basked in the pride of ownership that rubbed off from the NASCAR race-winner of the day.

Automotive aerodynamics was still a brave new world in the ’60s

Consequentially, the factories adopted a ‘win at all costs’ strategy, so without factory backing victory became nigh on impossible. The factories dished out their race cars and racing equipment through two leading race car builders, and potential Ford or Chrysler teams had to deal with one or the other. Holman-Moody, based in Charlotte, North Carolina, distributed the Ford racing iron, and Nichels Engineering in Highland Indiana was Mopar’s race car outlet. The full weight of both corporations’ engineering divisions backed the race teams to the hilt.

With millions of dollars of potential sales at stake, competition was intense, and the winners’ parade on victory lane see-sawed back and forth as the decade wound out.

Street Hemi

Then 1966 heralded the introduction of Mopar’s legendary 426 Street Hemi, finally homologated for NASCAR after two years of wrangling with Bill France. When the dust settled, Chrysler had racked up 18 victories for Dodge and 16 for Plymouth, easily beating Ford’s 10 and Mercury’s two. The next year was even better for the Pentastar brigade, with Richard Petty gaining his crown as King of Stock Car racing by clocking up 27 of Plymouth’s 31 victories — a record unbroken to this day — with Dodge picking up six wins and Ford 10, while Mercury sat on zero.

Then 1968 brought an end to the temporary Mopar reign, with Ford a clear victor with 21 wins, plus six for Mercury whilst Dodge only garnered five, and Plymouth took 16. Something had to be done, especially from Dodge’s point of view. Its new ’68 Charger won accolades for styling, but on the super-speedways the recessed grille acted like an air scoop, trapping air, and causing 567kg of front lift at 180mph — making the car extremely hard to handle. A front spoiler knocked lift back to around 227kg, improving the handling, but it caused unwanted additional drag. Compounding Dodge’s problem was the rear window’s near vertical angle, combined with the fastback rear pillars. This created a tunnel effect, causing lift at high speeds.

Dodge knew the Hemi produced more power, but the Fords and Mercurys were faster and that meant only one possible solution: the Charger had to be able to slip through the air stream more easily.

Dressed for combat

Automotive aerodynamics was still a brave new world in the ’60s. Cars were supposed to make power by brute force alone. Like its rivals, Chrysler had a military and an aerospace division to soak up dollars provided by lucrative federal contacts from Uncle Sam, and initially five aerodynamicists were recruited from these. They found that very little work had ever been done in relation to automobile aerodynamics. There was a total absence of engineering or scientific papers to refer to, and they literally had a blank slate to which to apply their knowledge.

Chrysler used two wind tunnels, the Wichita State University tunnel — which required the use of 3:8-scale clay model cars — and the Lockheed tunnel in Atlanta, Georgia. The Lockheed tunnel could take full-sized cars but could only be accessed through a 4.2-metre hole in the ceiling, designed to take scale model aircraft. Since the cars were 5.5 metres long a special cradle had to be made to lower them in at a 45-degree angle.

Aerodynamicist John Pointer solved the aerodynamics problem by stitching the flush grille from a ’68 Dodge Coronet into the Charger’s nose, and created a plug rear window to smooth out the buttressed C-pillar section. This upgrade was introduced to the motoring press in 1968 as the ’69 Charger 500, duly named for the 500 units Dodge would have to produce to homologate the model for racing. It actually only produced around 392 examples, but this didn’t stop them racing.

Producing this model on normal assembly lines was not a viable option, so Dodge gave the job to Detroit firm Creative Industries, which undertook custom work for GM, Ford, and Chrysler on a regular basis. Unfortunately for Mopar fans, Ford hadn’t been exactly sitting on its corporate hindquarters while the Charger 500 was race readied, and Holman-Moody partner, Ralph Moody, had significantly improved the already slippery Ford Torino and Mercury Cyclone by designing a lower nose and flush grille, further enhancing their aerodynamics.

Christened the Torino Talladega (after the new Talladega super-speedway being constructed in Alabama) and Cyclone Spoiler II, these ‘aero’ cars would do battle with the Mopars at the biggest stock car race of the year — the 1969 Daytona 500. The race was tightly fought and it all came down to the last lap, where LeeRoy Yarbrough’s Talladega nosed past Charlie Glotzbach’s Charger 500 to take the race by less than a car length. Even though the Ford was running a better choice of racing rubber than the Dodge, Special Vehicle Group’s head stock car engineer, Larry Rathgeb, realised the Charger 500 simply wasn’t good enough to take the Fords out of contention. It was back to the drawing board, and fast.

Charger Daytona

Chrysler was determined to be in the winner’s circle, ace driver Charlie Glotzbach duly noted, “It wanted to be number one and it didn’t care what it took to do it!” A new model, the Charger Daytona, had been planned for 1970, and this was unceremoniously shifted forward to 1969 for the grand opening of the Talladega Speedway on September 8 — months away. No doubt this was planned in order to upstage Ford’s use of the Talladega name. Five hundred cars had to be built for retail customers by then, and the model had to be introduced to the press by April 1969. At that point only hand drawings existed, two remarkably similar but unrelated concepts by John Pointer and Bob Marcell.

At the meeting that would kick start the creation of Mopar’s ‘winged warriors’, Plymouth’s management was noticeably absent. When pressed for reasons for the no-show, Plymouth’s Jim Stickler replied that since Plymouth had Richard Petty it didn’t need engineering’s help to win, a comment that would no doubt come back to haunt him since Petty, disappointed by the lack of a suitable Plymouth ‘aero’ car to compete with the Blue Oval boys, was poised to defect to Ford for a one year contract to drive a Talladega!

Initially the new car would be Dodge’s baby.

Green light

The next step was gaining approval from above from vice president and general manager of Dodge, Bob McCurry. Larry Rathgeb and Dodge product planner Dale Reeker fronted up with the drawings. “God it looks awful, will it win races?” said McCurry. Upon hearing the affirmative he gave the project the nod, adding, “If anyone gets in your way, just let me know and I

’ll keep the path clear for you.”

With the green light given, the race to develop the Daytona was on. Normal model development programmes went by the wayside, and the team was split into three groups. John Pointer, now a test engineer, was to co-ordinate the practical testing at Chrysler’s Chelsea Proving Ground’s high-speed five-mile banked oval track. The Aerodynamics Group, all six of them, were to undertake wind tunnel testing, and product planner Dale Reeker was to oversee Creative Industries’ efforts to build sufficient Daytonas to homologate the model for competition.

The primary goal of the Daytona programme was to come up with eight kilometre per hour, or a five mile per hour, increase per lap on the super-speedways. For the 426 Race Hemi to achieve that by itself, a 63kW (85hp) increase would be required over the 447plus kilowatts (600-plus ponies) it already cranked out, and this was simply unfeasible. Therefore the team decided to reduce aerodynamic drag by 15 per cent to obtain the same results.

A ‘mule’ was constructed for track testing, and the aerodynamicists set to work with 3:8-scale models at Wichita State, with full-sized data from Lockheed backing up their findings.

Finally a sloping nose cone measuring 462mm (18 inches) was chosen over a 231mm (nine-inch) rival, giving lower drag, better directional stability, and most importantly for the street models, providing a workable housing for the headlights. The rear wing kept the aerodynamicists busy in the wind tunnels, and initial studies showed the effects tapered off with a wing size over 15 to 17 inches.

John, who emigrated to nz from England, brought the daytona with him

The problem was that in order to open the Daytona’s boot the wing had to be 23 inches high, and the wind tunnel crew came up with the clever solution of using streamlined vertical supports, and an inverted Clark Y Airfoil, which pulled the car down rather than lifting it up. With the major problems sorted the project was moving at a fast clip, but then the all-powerful styling department, which had been left out in the cold up to this point, decided to muscle in. One leading stylist was determined to carve up the Daytona’s nose, and was met with a blunt refusal from the team. Throwing a tantrum in front of Dodge boss Bob McCurry, he was bluntly told by the chief, “I don’t give a sh*t what it looks like. It goes fast. If you can’t help, get out of the way.”

Daytona launch

The Daytona was officially previewed to the automotive press on April 13, 1969, but the motor-noters were actually shown a Charger 500 with a hastily constructed fibreglass nose and rear wing, while the mule was being used for track testing. After this, the final testing programme began in earnest to ensure the Daytona was ready for its September race date. The mule — which hadn’t been driven over 193kph (120mph) — was retired, a fully-fledged race car was built, and two top Chrysler Grand National race drivers were chosen for track testing. Charlie Glotzbach and Buddy Baker — both race winners in ’68 with numerous top-10 placings in Chargers — were selected, because as Larry Rathgreb succinctly stated, “They weren’t afraid to go fast!”

They ran the Daytona hard at Chrysler’s Chelsea Proving grounds, with its six-lane track that had maximum banking of 31 degrees. The Daytona was tested alongside a Ray Nichel’s Charger 500, and its first outings produced a 194mph top speed — only just faster than its Charger 500 sibling. Disappointing for some, but after the deed George Wallace, from the Special Vehicle Group, confessed that the Daytona was running a smaller carburettor than normal to restrict performance. Interest was running high over Dodge’s new winged cars, and light aeroplanes flying over Chelsea during testing were deemed to be full of Ford engineers, hence the subterfuge. A week after the first tests Glotzbach was lapping at 204mph and was raving about the balanced handling, stating he could drive at 180mph with one hand.

The final race package was an aerodynamic masterpiece, a rounded 18-inch nose, and a five-inch-wide 51-inch-long front spoiler reposed 13-inch back of the car’s leading edge at a 45-degree angle to the road. Front downforce was more than 90.7kg. The A-pillars featured streamlined wind deflectors. Out back the wild rear wing measured 58-inches across the car, was 7.5-inches wide, 23-inches high and could be adjusted from minus 10 degrees to plus two degrees. With a surface area of 0.28 square metres, or three square foot, it created 272kg of downforce. The drag coefficient was only 0.29.

Aerodynamicists Gary Romberg and Bob Marcell presented a paper titled The Aerodynamic Development of the Charger Daytona for Stock Car Competition to the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE), and Bob Marcell wryly noted, “Typically when you do an SAE paper you get about 25 people in the room to hear about it. Gary and I, when we did ours, we had 500 people in the room! It might have been a record — and the first two rows were aerodynamics people from Ford and GM!”

Racing debut

As Talladega loomed closer, testing continued unabated, and the car was driven at speeds no one had thought possible only a few years previously. Buddy Baker had a close shave whilst running at speed on the five-mile banked oval. “I came off the damn corner over there, running about 235mph and I looked up — and here is the biggest deer you’ve ever seen in your life, right on the back straightaway. I made a couple of little turns on the wheel, but whew! When I went by that son of a gun he just kind of bowed up in the back and that’s how I missed him. I was glad to see there was no fur on the windshield. And I don’t know who had the biggest eyes when I went by, me or him!”

The drivers had the Daytona dialled in on the Chelsea track, with Charlie Glotzbach clocking an incredible 243mph! As quick as the Daytona was on Chrysler’s banked oval, the real test was on NASCAR’s high-speed tracks, none of which were as smooth or half as long. The car was taken to Daytona International Speedway in Florida for a final shakedown, and then ran at the opening of Talladega, with Richard Brickhouse taking the chequered flag in the #99 Daytona. The victory was diminished somewhat, as a driver’s strike had prompted many of the leading teams to boycott the race in a protest over the newly laid track’s condition, plus Bill France’s unwillingness to come to the party by improving benefits for drivers.

Although winning the race, the Daytona suffered excess tyre wear, chewing through a set of racing rubber every five laps. Some of this could be attributed to the poor state of the Talladega track, which was subsequently relaid, but it appeared that the winged Mopar’s development was a little beyond the cutting edge of tyre technology, a situation that wouldn’t be resolved until the 1970 race season. The next race for the Daytonas was the National 500, at Charlotte Motor Speedway in North Carolina. The Dodges dominated at the start of the race, until their left rear tyres started to come apart.

Ford’s Torino Talladega, piloted by Donnie Allison, took the victory. The last race of the 1969 season was the Texas 500, at Texas International Speedway, a smooth newly-built two-mile banked race track. This time the Daytona was victorious, with Bobby Isaac taking the win. The 1969 NASCAR Grand National season was over, and Ford was still in the lead with 26 victories, while Mercury had four, and the Mopar camp had Dodge at a much improved 22, with Plymouth trailing badly on two. All this changed with the start of the 1970 season. Plymouth wasn’t looking happily at its abrupt demotion from the winner’s circle, and the tyre companies were belatedly catching up with Mopar’s winged warriors.

Richard Petty and the Daytona

Very few racing drivers can claim to be so valuable that major manufacturers custom-build cars for them, but the King of Stock Car racing, Richard Petty, definitely qualifies

for such an accolade. Plymouth, devastated by his one year defection to Ford, was desperate to get Petty back in the Mopar fold. “Will you come back with Chrysler if we build you a wing car?” Plymouth’s head honchos coyly asked, to which the King replied, “Let me see what you’ve got.” Petty Enterprises also took control of the Chrysler race car programme from Nichels Engineering as part of the deal. The final phase of Chrysler’s winged car programme was then put into place, and the Plymouth Road Runner Superbird duly joined the Dodge Daytona on the high banked ovals. Between them they carved the 1970 NASCAR season up like a turkey at Christmas.

Peter Hamilton won the Daytona 500 in a Superbird, while David Pearson was second in a Talladega, with three Daytonas hot on his heels. At the season’s finale, Bobby Isaac, driving the K&K #71 Daytona, was Grand National Champion on points, and on March 24, 1970, Buddy Baker went into the record books as the first ‘official’ stock car driver to clock the double ton, piloting the #88 Chrysler Engineering Daytona around Talladega at 200.447mph. A vintage year for Mopar performance, with the final NASCAR tally at Dodge with 17 wins, Plymouth 22, and Ford trailing on only six, Mercury four. The winged cars had proven their mettle, a task made easier perhaps by the fact that the ’70 Fords and Mercurys weren’t as slippery as their ’69 predecessors, so the Ford brass let the top teams run in the ’69 cars.

Banning the aero cars

Bill France pulled the plug forever on the aero cars in 1971, signing the death knell of an era with draconian new rules. “Special cars, including the Mercury Cyclone Spoiler, Ford Talladega, Dodge Daytona, Dodge Charger 500, and Plymouth Superbird shall be limited to an engine size of 305 cubic inches” (4998cc). That was the end of the ‘aero’ 429s and 426s. The all new ’71 wing cars, which were undergoing scale model wind tunnel testing, were swiftly canned, and both Ford and Chrysler pulled factory support from the race teams. Race factory budgets were slashed — something that NASCAR boss Bill France had long desired.

NASCAR, which France had built from scratch, was very much his kingdom, and he didn’t appreciate the overt control the factories had developed over the cars and drivers. So he simply legislated them out of existence, or so he thought. One race team decided to build a 305ci Daytona, and Chrysler (probably out of spite) decided to fund it. Mario Rossi’s red and gold Daytona had been a top contender with Bobby Allison at the wheel in 1969 and ’70, and they got engine builder Keith Black to construct a 305 Hemi, which was nicknamed the ‘lunchbox’ as in — ‘hey man, someone left their lunchbox under your hood.’ It would wind out to 10,000rpm, as opposed to the big Hemis, which went to around 7000. The only aero car on the starting grid at the 1971 Daytona 500, it must have given Bill France nightmares when Dick Brooks assumed the lead, and held it for 18 laps before colliding with Pete Hamilton and losing a lap. He finished in seventh place, and it was the last time a winged Mopar ran in a Grand National race.

Record breaking

The Daytona hadn’t finished with the record books, though. In September 1971 Bobby Isaac and his top-rated crew chief, Harry Hyde, hauled the #71 K&K Daytona to Bonneville Salt Flats as Hyde had a hankering to break the stock-bodied car world land speed records as sanctioned by the United States Auto Club (USAC).

The condition of the salt that year meant that rather than the 10-mile circle that’s the track of choice at Bonneville, they used a 10-mile oval — that suited Isaac, who was one of the greatest dirt-track racers of all time. He wouldn’t button off at the end of the straights at 205mph, hanging the tail out instead, just as he would on a dirt-track. USAC’s chief steward, Joe Petrali, told him he had never seen any driver dirt-track it around Bonneville before, to which Bobby Isaacs replied, “Maybe I ought to get credit for going 200mph sideways!”

All up the #71 Dodge broke 28 records, some of which still stand. Isaacs ran a one-mile run of 216.946mph, a one-kilometre run of 217.368mph, a 100-mile run of 194.290mph, and a standing start 10-mile run of 182.174mph.

Harry Hyde had built a strong 426 Race Hemi, but he gave the rear wing the principal credit for the speeds obtained, stating that the downforce the wing generated held the car onto the salt pan. Hyde, whose illustrious career with NASCAR racers lasted well into the ’90s, was interviewed just before his death in 1996, and had nothing but praise for the Daytonas. “There is no telling how fast they would have run,” he said; ” 280mph would not have been out of the question with the tyres we have today. But it really just is a guess, as they were almost the perfect race car. They had really low drag numbers, and we all know how important low drag numbers have become.”

The road cars

By speeding up the Daytona development programme Chrysler just squeaked in using the 500-car quota, which was changed for 1970, making Plymouth produce a number of Superbirds equal to half the franchise dealers in the United States, which was a lot greater. Dodge still had its work cut out, as all the 500 cars required had to be in the dealers’ showrooms by September 1, 1969, to enable the Daytona to run at Talladega two weeks later. Creative Industries leased a disused assembly plant in East Detroit, and R/T Chargers were shipped there from Chrysler’s Hamtramck plant to be converted into Daytonas.

The operation was tightly wound, with a schedule that had no margin for error, but Creative Industries handled the task with aplomb. In addition it had to make the aerodynamic kits for all the racers who chose to convert their Charger 500s into Daytonas, to save valuable time. The production ‘street’ cars came standard with Chrysler’s 375-horse 440 Magnum (280kW from 7210cc), with the 425hp 426 Hemi (317kW, 6981cc) optional, both available either with Chrysler’s 727 TorqueFlite automatic or the A833 New Process four-speed manual. While most Charger options could be had, air conditioning was off the list, as it would cause major engine cooling problems at low speeds.

It was priced at an incredibly low US$3993 for a 440 Daytona (a standard R/T 440 Charger was $3592). Dodge lost around $1500 per car sold to the public, but that wasn’t an issue, and 1200 orders in three weeks ensured the car would race as planned. Actual production numbers, as for many Chrysler products of that era, are hard to verify, mainly due to poor record-keeping at the time. However, a general consensus is that between 503 and 505 Daytonas were produced for the US market, with Hemi 426 figures ranging from 32 to 70. This doesn’t take into account the converted Charger 500 race cars, or approximately 50 Daytonas that were supposedly exported to Canada. It is believed around 350 Daytonas exist today.

John’s Daytona

Our featured Dodge Daytona is owned by 48-year-old Air New Zealand aircraft engineer, John Houlihan, who also proudly possesses a 440-6bbl six-speed Plymouth Superbird. John, who emigrated to New Zealand from England, brought both cars with him, to the boundless delight of Kiwi enthusiasts, and is a member of the American Muscle Car Club. Any Daytona is a special car in its own right, but John’s EV2 Hemi Orange winged warrior has its own unique chapter in the Daytona history pages.

The car was purchased on February 18, 1970, by the California Liquid Gas Corporation, known most as Cal Gas. With a 440 four-speed manual and a Dana 354:1 rear, the Daytona was converted to a mobile clean air dual-fuel showroom. CNG was the main fuel, but rather than switching back to petrol, the Daytona automatically sourced an LPG tank for back-up fuel. The Cal Gas technicians removed the petrol tank, re-located the spare tyre, and fitted the LPG tank in its place. Most of the boot space was taken up by the CNG tank, and an Impco CA 425 mixer replaced the 4bb

l carburettor.

When the CNG line pressure dropped to 50 to 70psi, an electronic lock-off shut the CNG and automatically opened another lock-off valve to let LPG flow to the converter. Passing the stringent 1974 California emission laws when built, the Cal Gas Daytona was sold in 1973, having outlived its usefulness as a promotional vehicle. Painted blue, the Daytona was bought by Brian Thornburg from a used car yard in Corning, Arkansas, for his daughter to drive. She didn’t like the manual gearbox so it was removed, and a TorqueFlite automatic was fitted. All the Cal Gas equipment was removed at this time also.

Chequered history

The car was involved in an accident in 1977, trashing the nose cone and a guard, and was parked until 1979, before being shipped to a body shop in Bloomfield, Missouri. There the Daytona sat, abandoned outside the body shop, rusting away, with a seized motor. Word eventually got out to the winged car clubs about this neglected example, and Californian Ken Finwall bought the car, sight unseen, for the princely sum of $3000, in August 1984 and shipped it to Rancho Palos Verdes, CA. The Daytona was then substantially restored and returned to its original Hemi Orange colour and four-speed manual gearbox. Ken was offered the original transmission and propane conversion gear by Scott Dorris, of Greenville Missouri, but foolishly declined to purchase them.

There the story may have ended but for John Houlihan’s desire to own a winged Mopar. Flying to California from Middlesex, England, in November 2000 to purchase a Superbird, John was somewhat less than impressed to find the car had been sold out from under him while he was in transit, and he promptly returned to England. Scanning Hemmings Motor News he spied a Daytona for sale in California in August 2001, and this time the vendor was happy to hold the car until John flew in. Shortly thereafter he was the new owner of the Cal Gas Daytona.

He added the Plymouth Superbird to his stable just before moving from Middlesex to rural South Auckland in July 2003, and has been trying, albeit unsuccessfully, to contact Scott Doris to see if he can reunite the Cal Gas equipment with the car. In the meantime John can take pleasure from owning two of the most desirable and formidable American muscle cars — both built for only one purpose; to conquer all that came before them.

1969 Dodge Daytona – Street Specs

Engine: 440ci Magnum

Capacity: 7210cc

Comp. Ration: 9.7:1

Power: 280kW (375bhp) at 4600rpm

Torque: 650Nm (480lb/ft) at 3200rpm

Transmission: TorqueFlite three-stage automatic (std) A833 New Process four-speed manual Std Chrysler 8 3/4 3.23:1 (Positraction optional) Track-Pak Dana 9 3/4 354:1(Std with 426 manual)

Brakes: Drum, optional front Kelsey-Hayes discs

Front suspension: Torsion bars

Rear suspension: Asymmetrical leaf springs

Steering: Recirculating ball, Opt PAS

Wheels/Tyres: 14 by six-inch JJ, FR70x14 Redline 15 by seven-inch road wheels optional

Dimensions

O/all length: 5808mm (226.5 inches)

Width: 1962mm (76.5 inches)

Height: 1359mm (53 inches)

Wheelbase: 3000mm (117 inches)

Weight: 1650kg Track, F/R: 1531/1518mm (59.7/59.2 inches)

Performance

Standing 1/4: 440 automatic, 3.23:1 rear 14.48 at 94.83mph (152.6kph)

Economy: 21l/100km (11.3mpg, US) (440ci)

Price when new: 440 auto US$3993