data-animation-override>

“Published in New Zealand Classic Car Issue No. 214”

Gerard recalls the time when he was seduced by a luridly-coloured Torana XU-1

Ringwood Shopping Mall car park — a bland outer suburb of Melbourne — and it’s April 1992. I’m striding back towards my rental hack when, out of the corner of my eye, I see it. The sight hauls me up in my tracks, heart thumping, as I soak up the beauty of its curvaceous purposeful lines and, approaching slowly, I admire its wonderful gaudiness.

The lurid, orange-coloured LC Torana GTR XU-1 time warps me back to my boyhood when I hung over fences at Pukekohe and passionately watched my heroes do battle.

A proper inspection of the Torana at Ringwood is curtailed by the immediacy of weighty shopping, and a none too wildly car enthused partner. However, that ‘spiritual encounter’ galvanised something within me. Yes, it was late — I was 37 at the time — but not too late. I wanted one of those beasts and the chance to drive it like I stole it — it was time to finally fulfil my boyhood dreams despite being on the fringes of middle age.

Back in New Zealand, the bank account predictably didn’t offer much optimism to support my new resolution. Financial constraints, however, were not going to deter me as I tottered on the brink of a male midlife crisis. A swap advert in Trade & Exchange netted the perfect catch — a genuine Dolly Yellow 1970 Torana GTR XU-1, which I promptly exchanged for my bland 1982 Skyline coupe.

Jason, the XU-1’s previous owner, had sunk a disproportionate amount of funds into the car but had run out of enthusiasm or cash, or both. At any rate he needed a more suitable (read comfortable) machine for courting young women. He’d been happy to take over my quick but soft, cruise-control-style Skyline.

Aussie muscle

I have a deep abiding love for Aussie muscle cars of the ’60s and early ’70s — Monaros, GTHOs and Chargers — but none more so than for the XU-1. This probably stems from a David and Goliath mind-set — with the Torana being the more complete racing package in terms of power-to-weight, braking, fuel consumption and tyre wear. The opposition Falcons and Chargers ran heavier, bigger engines which, while faster at the outset, suffered quicker tyre and brake wear and more fuel stops.

We should all endeavour to realise at least one of our childhood dreams; especially essential for an obsessed petrol-head Kiwi. Deny this and the legacy of regret could last a lifetime.

Anyway, with the previously mentioned car exchange done, I drove my piece of motoring legend home in a euphoric state — largely oblivious to the Torana’s less than perfect state of health.

In the cold light of the following day, I’d realise that a few problems needed immediate attention — namely the brakes, valve gear and a horribly cobbled-up exhaust system. As well, the Torana’s triple carburettors were well out of sync.

But with the XU-1 safely ensconced in my garage, I broke out the Johnnie Walker and celebrated the realisation of a boyhood fantasy. It was the real deal — an absolutely original car with matching engine and chassis numbers. True, it was a bit rough around the edges but it was all there. On the plus side the engine and drivetrain were in rude health having just been refurbished, but the old bodywork wasn’t quite so sharp. The ordeals and torments in store occurred to me only briefly through the ensuing alcohol haze.

It was 1992, and I’d just purchased a 22-year-old much-thrashed classic in need of work. Never mind, the moment was exquisite.

Vanishing point

Enter one Doug Bremner — mechanic to legendary Torana XU-1 racer of the early ’70s; Ralph Emson. Emson was a long-time racer, at one stage in partnership with four-times NZ Saloon Car Champion, Paul Fahey. They ran an outfit called P&R Motors in the 1960s.

At the time of my XU-1 purchase, Emson was running a business in Takanini tacked onto a motorcycle shop I frequented. Ralph’s advice to me was to get in touch with Doug — “He knows XU-1s like no-one else.”

Doug, no mean steerer himself, had been a past NZ hill climb champion several times in his flat-six Corvair-powered VW Beetle in the ’60s and ’70s. He agreed to do some work on my car. It was a nice feeling having the Torana magician on the case.

The initial plan, once the machine was roadworthy, was a fast blast to Wellington. Up over the Desert Road, through the Rangitikei hill country and down along the Foxton straights to the capital city — a nostalgic revisiting of many childhood journeys in early Holdens.

Unfortunately, as a kid, I’d seen too many of those American road movies (bad acting but great muscle car action) and fancied myself in the lead role.

Characters such as Barry Newman played in his doom-laden quest in Vanishing Point. In that movie, Newman set out from San Francisco in his white 1970 Dodge Challenger only to become quickly embroiled in a desperado vendetta with the cops, and anyone else who got in his way. His efforts to evade capture and the continued destruction of vehicles cast Newman as a somewhat dubious hero.

Road warrior

Doug’s verdict on the XU1 was a heartening thumbs up. Having repaired the aforementioned ills, plus the driver’s door window cog — a part which proved elusive to find — Doug pronounced the car in good shape and in very original condition, with the exception of a few body panels. The carburettors were retuned and Doug suggested that reconditioning the triple side-draught Strombergs would be a good idea. Unwisely, I elected to postpone acting upon Doug’s wisdom in this area.

Fortified in the belief all was well, I rumbled out of Auckland in the depths of winter 1992, Wellington-bound. However, there is nothing quite like a lengthy run to discover shortfalls in a freshly acquired car that would be undetectable on a sunny Sunday afternoon run. While the sun shone I hammered away in good humour, revelling in the XU-1’s rocket-like acceleration and mowing down entire queues of slower traffic. The Desert Road proved to be an exhilarating ride as I enacted outlaw-on-the-run fantasies and indulged myself fully in the pure pleasure of the machine.

As Hunter S Thompson, the great creator of gonzo journalism, wrote in his cult classic book, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas — “Here indeed was a machine eminently suitable for highway work.”

South of Waiouru, ominous dark clouds signalled a change in the weather and my euphoric mood. Single-speed (slow) wipers and a poor demisting system did not equate with the awesome power at the disposal of my right foot. I gained a renewed appreciation of modern automobile technology.

Yes, I was having difficulty seeing where I was going! Oddly, I don’t ever recall my celluloid heroes having to put up these types of setbacks. Another nagging irritation was the need to strain against the fixed location seat belts to flick the dash wiper switch on and off in the drizzle. It was clearly time to stop and take stock — and indulge in a few recollections.

Winning at the mountain

It was known as Standard Production racing, but there was very little that was standard about these vehicles. As modifications were not allowed for machinery competing in the all-important Bathurst races between 1968 and 1972, an era of factory-built race cars was spawned. The performance limited edition specials built by Ford, GM and Chrysler’s Australian subsidiaries have since become legends. Each corporation endeavoured to outdo the others in their efforts to produce a road-legal machine capable of winning the annual duel at Mount Panorama.

It wasn’t long before a similar category was set up to race these cars in New Zealand, with many of the leading drivers and car companies importing Aussie muscle cars to do battle on Kiwi race tracks.

Race fans had a fierce loyalty to their favourite marque — be it Holden’s Monar

o GTS or Torana GTR XU-1, Ford’s various GT Falcons and Chrysler’s Pacer and Charger R/Ts.

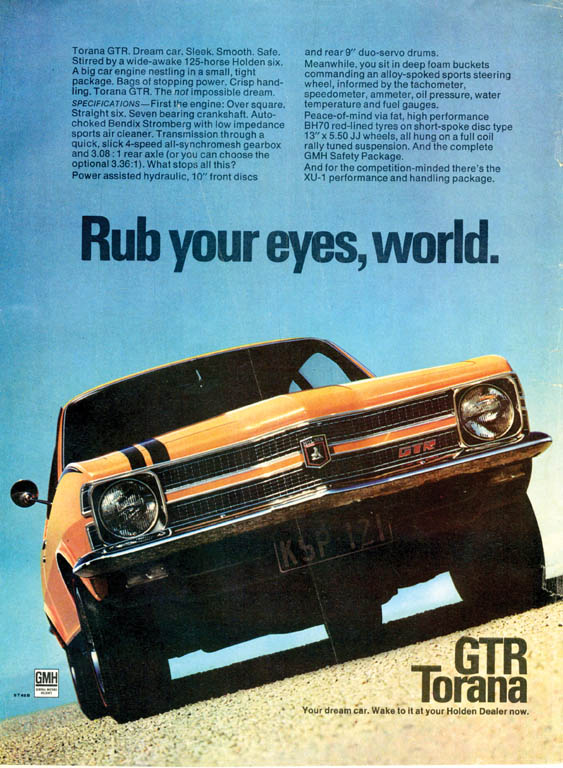

The era was a visual symphony — lurid, electric colour schemes with plenty of blacked out panels, stripes and badges. The interiors were always coal-black. The flavour was very much that of the pony car movement that had been initiated by the Mustang — but now transplanted to Australasia.

To a young boy of 15 in the Pukekohe paddock, these cars reeked of charisma, power and excitement. Remember the pit scene as a kid at a big race meeting?

We’re in a line of traffic still waiting to park in some perimeter paddock, the circuit seems miles away and I’m aching to be there. The sweet aroma of high octane racing fuel is intoxicating, the excitement is running in my veins and tingling up my spine. Somewhere in the distance there’s the urgent crescendo of racing engines being tweaked. The cacophony of raucous fours, the howling sixes and magic V8 thunder draws me like a magnet.

I am beside myself with anticipation as we enter the arena, a kaleidoscope of vivid colour and aural assaults. Everything seems larger than life, mechanics and crews cluster around name drivers in earnest consultation. I hover, trance-like, soaking it all in. The saloons have the greatest visual impact in their gaudy colours, brash sign-writing and huge tyres.

Kiwi Toranas

I see a name driver’s XU-1 Torana and choke up with passion and yearning — the beauty of its menacing presence. The black vinyl cavern-like interior where my hero fights his noble battles from the gladiator’s seat, protected by a roll-cage, full seat harness, fire extinguisher. All reminders of the perils of his pursuit.

My favourite local XU-1 driver was the redoubtable Richard ‘Paddy’ Brocklehurst. His LC XU-1 was bedecked in the classic yellow and black just like mine. The date was early 1971.

Other leading local XU-1 punters of the time were, Jimmy Palmer, Kerry Grant, Ralph Emson, Roy Harrington and Merv Neill, to name but a few. Pukekohe, with its long back straight, was a track that favoured V8 power and didn’t help the six-cylinder XU1 despite its handling and braking advantages.

At the March 14, 1971, Saloon Championship meeting, Brocklehurst was right on form claiming pole position with a time of 1.20.2s, just shaving out the Robbie Francevic’s big McMillan Ford-sponsored Falcon GTHO which closed 1.20.4s. Jim Richards was third fastest in his Monaro GTS at 1.21.2s.

Other leading contenders included Frank Radisch (father Paul Radisch) in a Monaro GTS and Spinner Black in a GTHO. Behind the four V8s were the three other XU-1s of Ralph Emson, Roy Harrington and John Murphy.

In the race Brocklehurst led bravely in his XU-1 and gallantly fought off the four V8s breathing down his neck for several laps. I watched transfixed, willing him on as he was overwhelmed on the long back straight. However, he swept back into the lead under braking. Francevic was forced to brake earlier, to slow his heavy car for the tight hairpin bend at the end of the straight. Eventually, on this occasion, Robbie got ahead and just held on until the chequered flag, but it was a close thing with Brocklehurst harrying him all the way.

The other three XU-1s filled sixth, seventh and eighth positions behind the V8s of Richards, Radisch and Black. Brocklehurst’s drive had been a superb effort and has remained etched into my memory to this day.

The Torana XU-1s greatest moment was, of course, Peter Brock’s epic win with his LJ 202-powered car, over Allan Moffat’s Phase 3 GTHO at Bathurst in 1972. Brock went on to a glorious victory, the first of an unprecedented nine wins, but it remained the XU-1’s only success in the Great Race.

Back to reality

Having broken my journey to recall my favourite Torana memories, I was brought back to reality by the thought that the critical factor with an engine running two or more carburettors is that they should all open and close in close synchronisation.

When they don’t you — or, more correctly, me — are going to engage in some strife, especially when you’re 645km from home base. Yes, the beast’s triple Strombergs chose this moment to decide that the carburettor reconditioning Doug had advised was now required! A tuning shop in Wellington quickly reset the jets, and I set forth with everything crossed for the return journey.

Around the middle of the North Island, once again on the Desert Road, the Strombergs relapsed. Then the steering wheel worked loose! It’s a nasty experience when you have to keep going, when some carbs are opening and others are closing at the same time and all the while you’re trying to hold the wheel in place. I made it back to Auckland with the sense that the expedition had not been a complete success, and I resolved to prepare more thoroughly for my next XU-1 adventure.

A complete body restoration was, I felt, in order, so I embarked on the hazardous business of finding someone skilled enough to do a quality job. Throughout the winter of 1994, the ongoing saga with the panelbeater continued, like a scene from the movie Groundhog Day. There were various hold-ups and explanations to justify lack of progress, but every time I turned up at the shop, the Yellow Streak was always languishing in a dark corner.

The long awaited Xmas excursion was looking dubious, though the Torana was finally completed in the nick of time, at the cost of a stroke-inducing budget blow-out.

The last thrash

Financially I was going down the gurgler, strapped for cash and with a broken relationship, I borrowed a wad of bucks ($600) from the old man then pointed the ‘Yella Terra’ out of town.

Another Hunter S Thompson quote; “You can only stay on the throttle for so long.”

I entered the true spirit of the classic machine on this journey. Sensing my time was nearly up with the XU-1, I headed out for the big thrash and covered as much twisting blacktop as I could.

The bone-jarring race suspension and uncomfortable vinyl bucket seats of this early spec XU-1 were aspects that always appealed rather than detracted from the car’s allure. Later versions had slightly softer suspension but with this baby, hitting any reasonable-size bump thumped your head into the roof. You really knew you were driving a race car.

Its handling, regarded as good in its day, would now be seen as abysmal and it had a tendency to sledge and drift in corners. I found this very reassuring, whereas today’s sporty cars stick like glue and then break away without any warning.

All went well until I got to Wellington. What is it about this town? I’d just arrived and the beast developed an electrical fault that seemed to be beyond the resources of local auto electricians to diagnose. The prospects of getting the engine running on all six cleanly were not looking good.

The mighty 186 ran beautifully on the run south, gutsy and crisp, but now I was in the capital it was banging and missing as effectively as one of John Banks’ political tirades.

Once again, I had strayed from the script and got away from the golden race track memories of my boyhood. While I pondered life’s evil reversals with the hood raised, a young petrol-head offered to check the Torana’s HT leads. Rather matter-of-factly, he stated that one was no good. “Replace it and you’re away mate!” So much for the experts.

Spirits lifted — and the mill blasting beautifully — I hammered through the Rimutakas and down into the Wairarapa, lights ablaze. Driven on by a demented urge to keep covering ground fast after the frustrations of the capital, I wound down to make a pit-stop in Woodville.

In a contemplative mood I supped on a large, cold one in the aptly named Railway Hotel, a fine old colonial edifice. My mind was drifting, as I reflected on the yellow machine lurking outside in the sunlight. My thoughts recalled the legendary American driver, Dean Moriarty, hero of ultimate be

atnik writer Jack Kerouac’s classic ’50s escapade, On the Road. Momentarily, I entertained wild delusions of being a kindred soul with the famed paranoid non-stop, cross-country desperado driver. Yeah, wouldn’t it be great to jump in a car and drive at insane speeds for days on end, with no particular destination?

“You can only stay on the throttle for so long,” repeats in my head. Damn right! I had a few more days out on the edge before this show is done.

Relentless

The rocket-ship was running like magic and felt as if I were driving relentlessly anywhere that it’d take me. Windows down, mirror shades on, the hot summer air rushing in and the backcountry sucked into the slipstream. I was having dangerous delusions of my superb ‘steerer’ skills.

Out of Bulls, on the road to Wanganui, looming up fast in my rear view I spotted a twin-cam FX-GT Corolla. I was definitely holding him up through the twisties and as we come onto a long downhill straight, the FX hung alongside me for a few moments. But there’s no substitute for capacity. A delicious moment, as I observed the rapidly diminishing Corolla.

The beast, as a young nephew of mine aptly named the XU-1, always drew attention wherever we went — some unwanted.

More often though, the car drew cult-like admiration from young Holden worshippers — those not born when the XU-1 first turned a wheel in anger. At the other end of the spectrum were the veteran enthusiasts.

There were a few more vignettes to play before the curtain finally came down on this heroic chapter. As my personal life continued to unravel, word of my odd and crazily irresponsible antics started to leak out. A run to Port Waikato with a crate of DB in the boot saw an ill-advised speed attempt. Just south of Tuakau on the Port Waikato road, dropping down a hill the road runs straight as a die across the valley floor for several kilometres. With my two young nephews in the machine, a genuine 172kph (107mph) was registered on the speedo with the team roaring encouragement. The telegraph poles were screaming by like a picket fence and keeping the bouncing, yawing machine tracking straight was a grim business. Bloody stupid really.

Another brain-disengaged blast was a ride out to Auckland’s wild West Coast beaches. The Scenic Drive run through the Waitakeres was the ultimate challenge in the twilight days of this era. I was lucky not to rearrange myself — or anyone else for that matter — on that run.

The final parting

With my life changing, I no longer had a garage so caring for a rebuilt classic car was becoming a problem. The writing was on the wall, and it was time to pass the beast on to the next foolish dreamer. Life has such weird twists — I’d thought that the XU-1 would be with me for years, but now it felt right to flick it on. Anyway, I couldn’t bear to watch it deteriorate.

This action also safely side-stepped any thoughts about testing long-harboured delusions of being a heroic racing driver. The classic saloon category was thus spared from my awesome domination and uncanny car control. It also allowed me to avoid the harsh probability that I would probably be hopelessly inept as a race driver. Yes, fantasy is a lot safer than reality — but much less fun.

Anyway, 1995 was the end of my road with this thoroughbred. A procession of car fairs and adverts finally dredged up the right person — another passionate young man under the watchful tutelage of his classic racing father. It was a deeply moving experience seeing the XU-1 heading off to a good home, destined to return to the race track for which it had originally been created.

I was left with the wonderful memories. Out on the open road, gunning that superb engine, front end rearing under fierce acceleration as I’m slammed back in the seat. A cursory eye on the tacho, straight arms gripping the thin-rimmed steering wheel. Poised to snatch another cog via the stubby shifter. Lashed down low in the vinyl bucket seat, ready to hurl the beast through the next sequence of curves. Petrol-head heaven!

Owning the XU-1 gave me a licence to revisit wild boyhood dreams. It had been time to go out and play, as I’d wanted to do when I was 15. All things have a beginning and an end, but the legacy of my journey with the Yella Terra will remain with me forever.

Words: Gerard Richards Photos: Terry Marshall/Gerard Richards