data-animation-override>

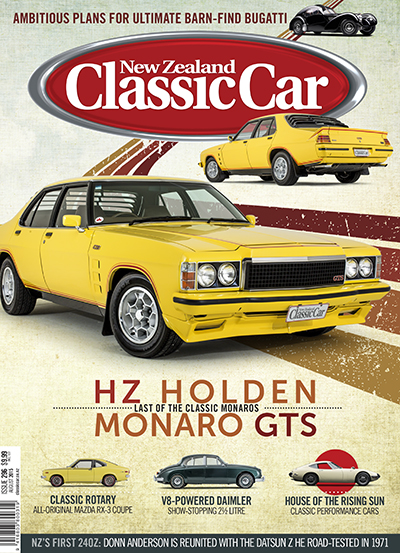

“Donn is reunited with the actual Datsun 240Z he road-tested more than four decades ago”

Cover of the November 1971 edition of Motorman, shot at Ardmore airport

Ken Brough agrees, the longer you keep a car the less likely you are to sell it — and moments after he told me that he would have to cut off his right arm rather than sell his Datsun 240Z, the Te Awamutu enthusiast revealed a profile of the 240Z tattooed on his right arm.

You need to be a rabid follower of a particular car to have its outline emblazoned on your body, but Ken’s that sort of bloke. In-between designing helpful machines for farmers, and racing speedway, Brough just loves spending time with his Datsun — a car he’s now owned for 18 years. And it is a rather special 240Z, as the message inscribed on the number plate surround indicates. The car still carries the original silver on black plates with the registration FV4253, matching the car that graced the cover of Motorman magazine in November 1971.

It is rare to see a vehicle you drove 44 years ago, but Ken was more than happy to drive to Auckland to reunite me with the memorable machine. What’s more, this was the first 240Z to arrive in New Zealand. Registered on August 11, 1971, by the local Nissan Datsun distributor, it was used for promotional purposes and driven by the company’s managing director, Keith Broadbent. Two examples of the brilliant Datsun actually landed here in the initial shipment and Ken, being Ken, was keen to track down the other car. He spotted FT2185 for sale three years ago with an asking price around $20,000. It went to a Christchurch dealer with 93,000 genuine miles on the clock (149,669km), and four months later was on-sold to Malaysia for $30,000.

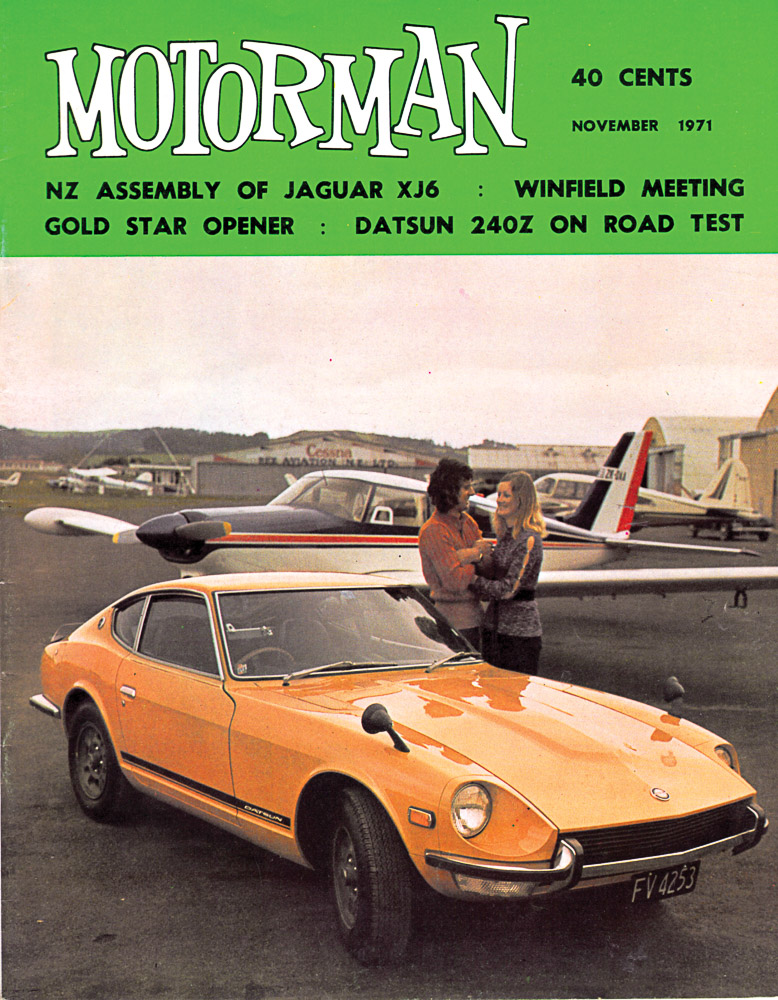

The Motorman 240Z — now painted red — in exactly the same spot at Ardmore airport in 2015

Something you love

One of the joys of owning classic cars is that they usually do not depreciate. When Brough bought FV4253 from a Wellington owner in 1997 it cost him $7000, and today he reckons its value is well north of $30,000. Not that he is likely to ever part with the car — you just don’t sell something you love.

Ken had long been keen on Datsuns, owning a 1200 coupé which he described as bulletproof. In the late ’70s he bought a 160J SSS that he ran for seven years. By the time Ken acquired the 240Z it had already racked up 23 owners, 10 of which were dealers, the car having spent time in both North and South Islands. Originally painted in Safari Gold, the 240Z had since been resprayed red, the gearbox had failed, and the original 2393cc L24 engine had been replaced by a longer-stroke 280Z power unit. This removes some of the car’s originality, but there’s naught to be done when you are the 24th owner.

Today, FV4253 is very much a ‘survivor’ car in unrestored condition. Apart from rebuilding the front suspension, Brough has done nothing to the Datsun, although he says he intends to eventually get around to more work. Yes, the car has ground to a halt occasionally and the shocks are on the way out, but nothing major has happened during his tenure and, until a year ago, it was Ken’s daily driver.

FV4253 is an early right-hand-driver with a low chassis number of 920, and currently has covered about 130,000 miles (209,215km) from new, although you can never be sure with so many owners.

Rising values of the 240Z are aligned to the brilliant design, and the lack of right-hand-drive examples worldwide. Ninety per cent of the 168,584 240Zs made between 1969 and 1973 went to the United States. In addition to the 148,115 sold in the USA, 11,198 went to Canada, and a further 5303 left-hookers found their way into European markets. Australia was the biggest recipient of right-hand-drive 240Zs (2358) and while the car found a ready market in Britain, only 1929 were sold there.

Nissan Motor Distributors estimates a mere 30 or so new 240Zs were imported into New Zealand. The model was only available with an overseas funds deposit, and the initial price of $5052 in 1971 rose to $6208 the following year. In Japan the 240Z was known as the Fairlady Z but, remarkably, only 420 were produced for the home market, so the total number of HS30s (the code name for right-hand-drive 240Z/Fairlady Z) is less than 5000 units.

Ken Brough with his much-loved 240Z and a poster-sized blow-up of the Motorman cover from 44 years ago

Enduring quality

Was this the car that made European and North American car makers finally realize the Japanese had arrived?

When I road-tested FV4253 in the early ’70s it was a crowd-stopper wherever it went, and Ken Brough says it still is today, attracting favourable reactions from other motorists, particularly from younger people.

From day one, not only was the 240Z a stunning looker, it was also a respectable performer. A top speed of 203kph (126mph) and zero to 100kph in eight seconds is good enough now, but in 1971 it was well ahead of the play.

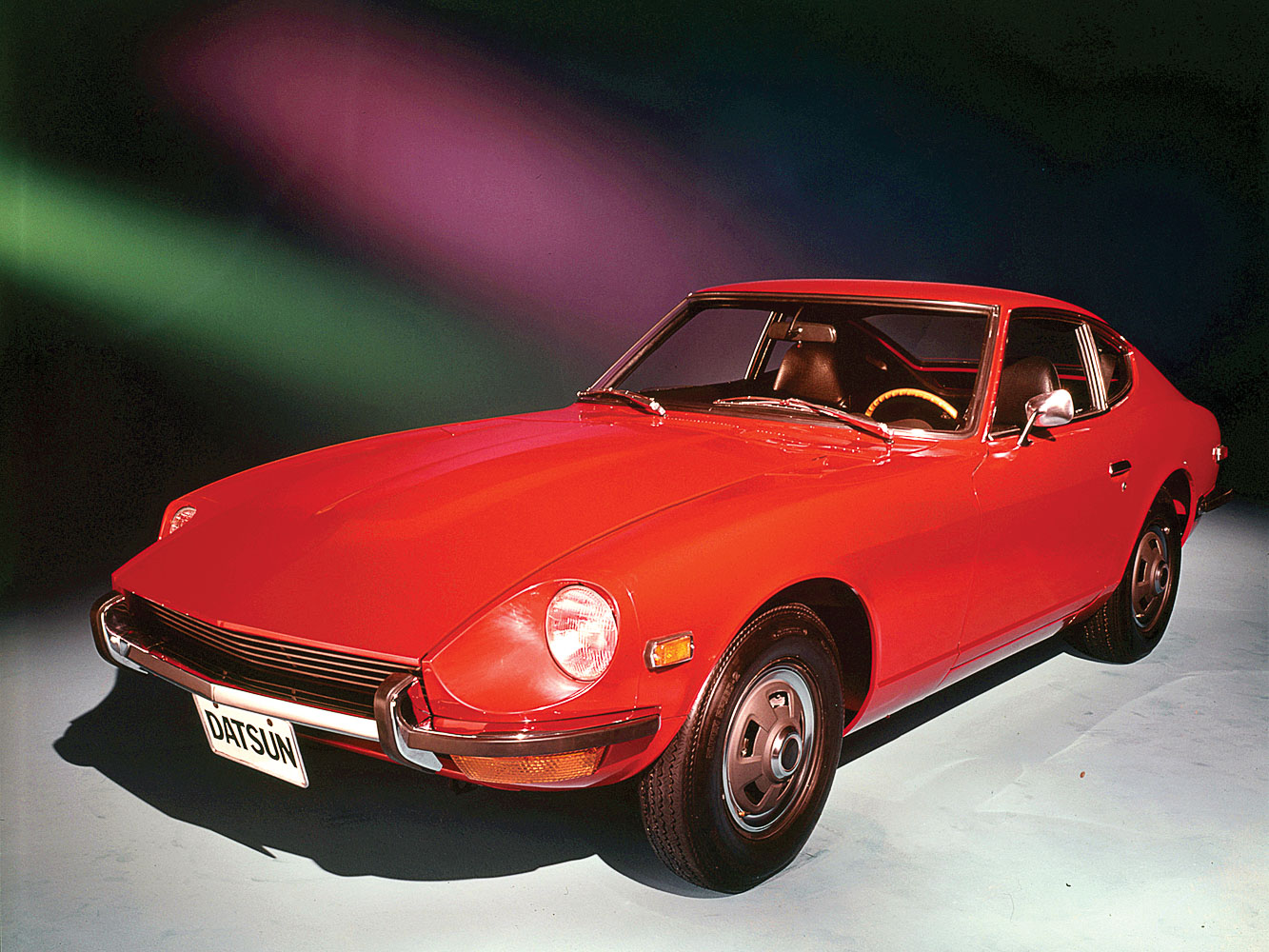

The thing about the 240Z, and its facelifted 260Z successor, is the enduring quality of the design. Cast an eye over the styling and this car still looks good. Austrian Albrecht von Goertz, who penned the BMW 507, was involved in styling exercises and helped shape the car that exuded inspiration from the E-Type Jaguar, Porsche 911, Aston Martin DBS, Ferrari 275 GTB and Mustang fastback. Goertz was not involved with the final design, however, that being credited to Fumio Yoshida.

Ironically, top management at parent company Nissan regarded the projected sales of 3000 240Zs a month by the project team as “wildly optimistic”, and initially decided to build the model in the company’s Shatia Koki facility, an old pre-war wooden factory in which car bodies were still moved around on dollies. The shiny suits were soon surprised by the sensational reaction to the car in North America.

Smooth, uncluttered lines of the 240Z. Steel wheels and hubcaps gave a hint to the car’s inexpensive price tag

Wow factor

Late in 1967, the four-door Datsun 1600 sedan went into local assembly in New Zealand and it was, without doubt, the best Japanese car you could buy at the time, and a clear indication Nissan meant business. But of course, the 1600 could not match the wow factor of the soon-to-be-released 240Z.

Unveiled at the Tokyo Motor Show in 1969, the car went on sale in the United States in mid-1970, and more than a year later there was still a six-month waiting list. Nissan was shipping 2500 240Zs to the States each month, while the maker put actual demand at around 4000 cars.

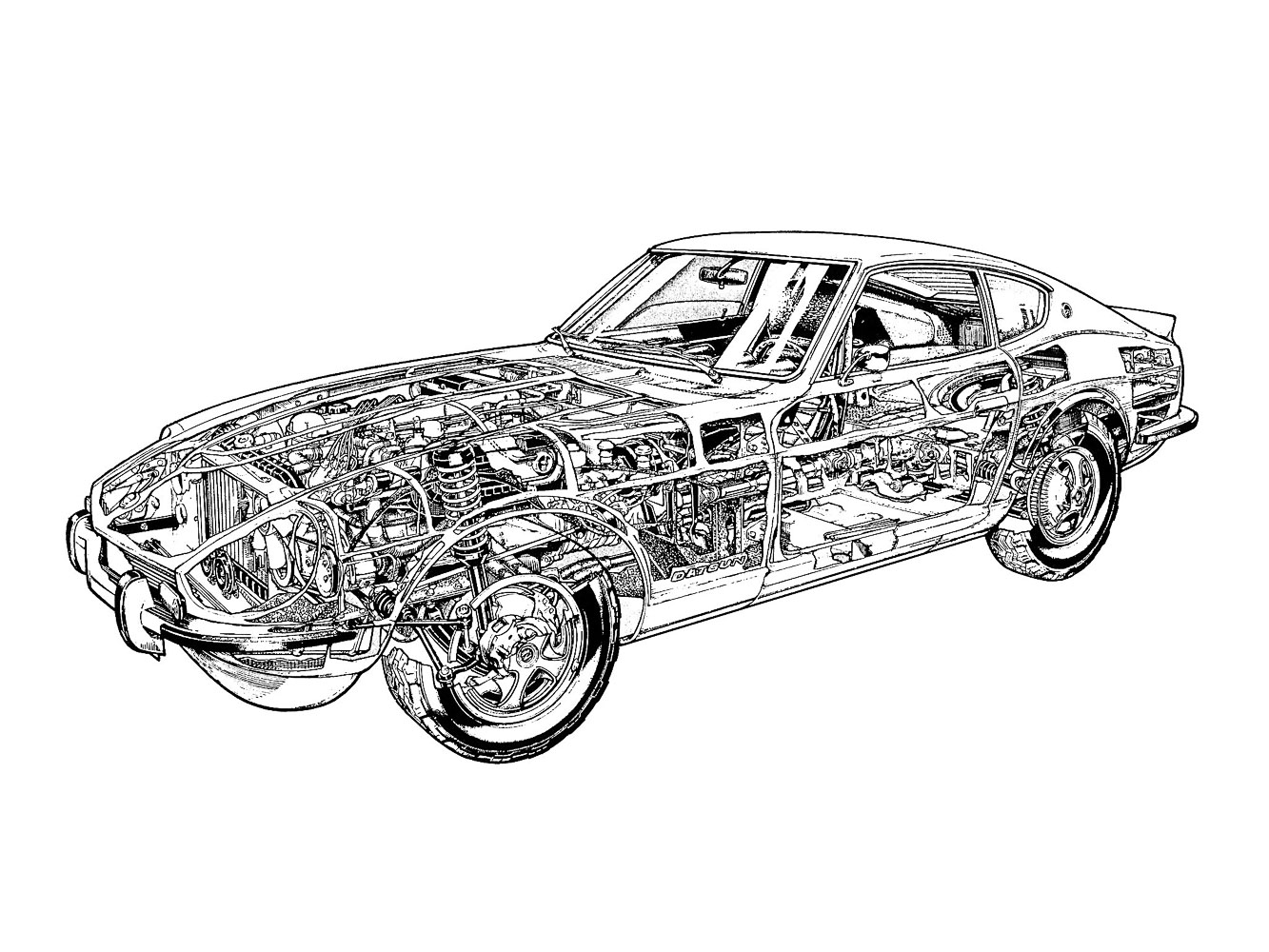

A low frontal area and clean, well-proportioned lines were the key to this Datsun. Perhaps the car looks slightly nose-heavy with the long front-hinged bonnet and short tail, but weight distribution is better than it appears since the engine is mounted well back. Just over half the dry weight rests over the front wheels.

Superb profile of the 240Z, with lines that have not dated

Boasting good proportions between the body and greenhouse, plus overall styling that is almost impossible to dislike, the 240Z was always destined to be a winner. Of course the car was built down to a price, evidenced by the standard fitment of steel wheels with hubcaps, and a seam line between the sugar-scoop headlight surround and front guard. Many examples, like the Brough car, were refitted with alloy wheels.

Both the 240Z and 260Z used Nissan’s proven single overhead cam straight-six-cylinder engine. In the 240Z the 2393cc motor produced 113kW (151bhp) at 5600rpm and 198Nm of torque at 4400rpm, and the twin Hitachi (SU-type) carburettors spark a level of simplicity owners such as Ken like. Nissan lengthened the stroke for the 260Z, increasing capacity to 2565cc while power and torque went up to 123kW (165bhp) and 213Nm respectively.

In 1970, Road & Track magazine said the car “set new standards in performance and elegance for medium-priced two-seat GT cars.” British writer Roger Bell reckoned the 240Z was what the short-lived MGC should have been, but never was. The car also filled the gap left by the ending of the Austin-Healey 3000.

Detail shots of 240Z showing dashboard and rear load area

With good ground clearance and a lack of underside projections, the 240Z also proved a success in both racing and rallying. Edgar Hermann and Shekhar Mehta finished first and second with a pair of 240Zs in the gruelling 1971 East African Safari Rally.

Mehta was a brilliant Ugandan-born Kenyan rally driver who competed in New Zealand rallies on three occasions. He won the 1973 Safari in a 240Z, and became the only man to win this famous event on five occasions. Mehta suffered a near-fatal accident in Egypt while driving for Peugeot, and he also rallied for Audi and Lancia. He rallied a Datsun 160J Violet in New Zealand, but is best remembered for his international successes with the 240Z. Sadly, he died in London in 2006 at the age of 61, partly as a result of injuries received in the rally accident many years earlier.

The 240Z’s straight-six motor

1970s road test

My Motorman magazine story headlined the car as being “delectable”, and the article went on to note the 240Z was unique because it was both better and dearer than the average production sports car, yet cheaper than a classic high-performance two-seater. It exemplified the fact that, in 1971, for the first time the Japanese motor industry was now setting the standard.

While the 240Z engine felt under stressed, the five-speed manual gearbox version I tested was not particularly flexible, especially around town. The gear change was positive but needed a heavy hand and was sometimes a little obstructive, while the drivetrain was a shade clunky — a characteristic Brough confirms is still there today.

A sticky throttle also made it difficult to execute really smooth changes, but a second example offered proved much better. The gear ratios were well chosen to make best use of the short-stroke motor which many Nissan enthusiasts preferred over the 260Z power unit. Fifth gear is essentially an overdrive, ideally reserved for the open road.

Acceleration runs were a piece of cake, with rapid starts achieved by dropping the clutch at around 4000rpm. The motor still sounded sweet as a nut when revved to 7000rpm, and the car felt in its element on the open road. Despite hard driving over 300km, the test example averaged 10.8 litres/100km (26mpg).

Classic 240Z style

When accelerating or braking hard a fair amount of fore and aft pitching was induced, and the slow-speed ride bordered on harshness. Over 110kph the Datsun also revealed occasional signs of wind deflection and float, while overseas testers reported minor instability at speeds over 160kph

.

The 240Z came up trumps over our favourite 20km of twisting sealed road, with the independent rear suspension doing an impressive job while cornering on poor surfaces. It had the ability to better the handling of comparable MGB and TR6 sports cars, while falling short of an Alfa Romeo. There was only slight understeer, low body angles, and the 14-inch 4.5J-inch-wide drilled rims shod with Japanese Dunlop SP tyres gave good grip.

My 1971 road test commended the car’s reasonably positive steering and good lock, although the unassisted rack and pinion set-up was heavy, especially at parking speeds. Steering power assistance was a rare luxury in those days. While the disc/drum arrangement was power assisted, pedal pressures remained high, but the brakes had good feel and performed well from high speed.

The 240Z was also a successful rally car

On rural roads in 1971 the 240Z was an effortless high performer, and a class ahead of the tired-looking Transport Department Holden which trailed me for 15km!

Good features abounded, like popping the hatchback door to find luggage straps, two compartments behind the seats to accommodate the tools, a trouble-shooting light on a lead, and lift-out ash tray that gave access to the fuses. Like other Japanese cars, there were no complaints about build quality. The 240Z was also admired for the fact that it was strictly a two-seater, although when the model was replaced by the 260Z in 1974 a longer-wheelbase 2+2 became an option. In 1978 production of the 260Z ceased, and it was replaced by the bigger, fatter and heavier 280ZX that lacked the appeal of the earlier models.

The 240Z engendered new respect for Japanese car-making skills. It was, indeed, a landmark car, a turning point and, in later years, it became one of the first oriental cars to achieve bona-fide classic status. No longer would cars from the Land of the Rising Sun simply be regarded as cheap economical runabouts.

In 1997, Pierre’s Z Shop in Hawthorne, California, began producing ‘new’ restored 240Zs for $25,000 as part of a factory-authorized programme. Cars were treated to a bare-metal restoration using all-new parts and offered with a full one year, 120,000-mile warranty.

When I asked Ken Brough if he had a copy of Motorman with the 1971 road test, he produced no fewer than five of them. Then out of his car came a large poster-size blow-up of the magazine’s cover. He had researched the cover shot taken at Ardmore airport in south Auckland, and returned years later with his car to reshoot the photo in the identical location. That’s enthusiasm for you — but the 240Z is that sort of car.