data-animation-override>

“We’re tripping back to the Swinging Sixties with this svelte, sexy fastback coupé — the only one of its kind in New Zealand ”

Founded in 1897 by Thomas Harrington Ltd (1897–1966) and based in Brighton, UK, the main business of this coach-building company was in the construction of coach bodies on chassis provided by manufacturers such as Commer and Bedford. As the company grew, it relocated to Old Shoreham Road in Hove, close to Brighton. In 1930, a purpose-built factory — Sackville Works — was constructed, occupying 2.8 hectares. A decade later, the business employed over 600 workers.

Following wartime work manufacturing air-frame components, the company became experienced with light alloys. By the ’50s, Harrington was also getting the hang of glass-fibre work as well. They applied these newly found skills to produce specialized vehicles such as Black Marias, RAF crew buses, and Green Goddesses.

However, while such work would always be the company’s bread-and-butter business, during the early ’60s, Harrington also branched out into car modification — first with the Harrington Alpines then, a little later, with the Dove GTR4. Today, it is best known for its fastback coupé conversions of Sunbeam’s open-top Alpine sports car.

Alpine coupé

The tie-in with Sunbeam was natural for Harrington, as it had been a Rootes agent since the ’30s — car sales operating separately from the coach-building side of the business. The first converted Alpine, styled by Ron Humphries — who had also designed the Cavalier coach — featured a neatly constructed fibreglass top complete with a fixed rear window. A new rear bulkhead was also fabricated to allow the mounting of the rear part of the new roof and the fitting of a suitably shortened boot lid. The changes made during the conversion were permanent; returning a Harrington Alpine back to standard Alpine trim was not a practical option.

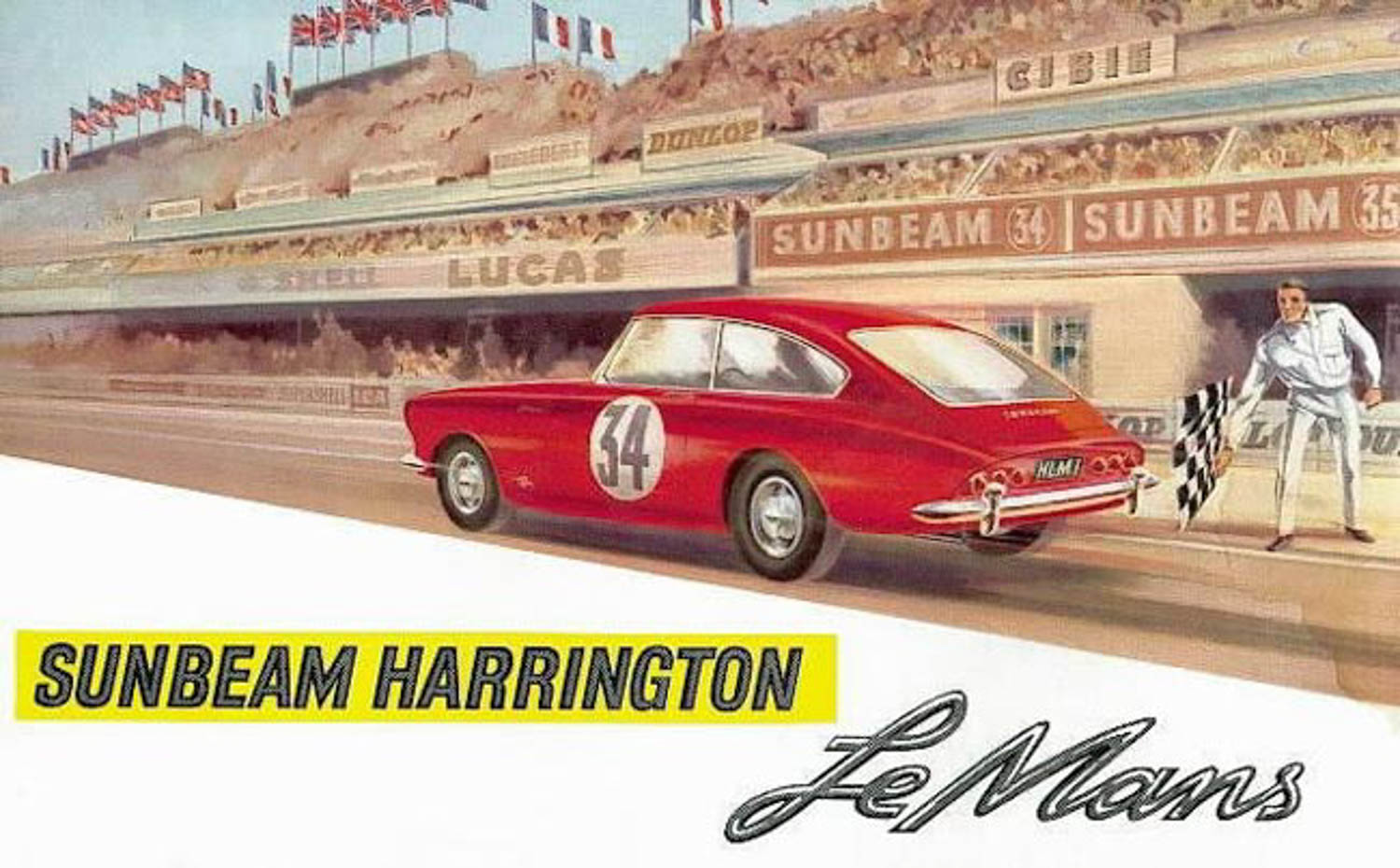

At the time Harrington approached it to discuss taking initial work with the Alpine further, Rootes was looking at getting into motorsport, and was already considering a closed-body Alpine in order to compete at Le Mans. The subsequent Harrington Alpine coupés were entered at Le Mans in 1961, 1962, and 1963 — famously, the Harrington Alpine registered as 3000 RW placed 16th overall and won the Index of Thermal Efficiency award. A Harrington-modified Alpine also competed at the Sebring 12 Hour Race in 1962 and 1963.

Following its success at Le Mans in 1961, Harrington soon got stuck into converting more Alpines, adding a new model — the Harrington Le Mans. For this model, Harrington cut off the production Alpine’s trademark rear fins to create a new look. While the earlier and later Harrington Alpines were essentially special-order cars, the Le Mans models were sold as completed cars in selected Rootes showrooms around the UK — although around half of Le Mans production was destined for sale in the US. All Harrington-modified Alpines came with a full Rootes new-car warranty.

In 1961, the Rootes Group acquired a stake in Harrington — still, at that time, very much a family business. Many believe Harrington became part of the Rootes empire, but this is incorrect — Rootes took its share of the coach-builder indirectly via Robins & Day, a company owned by the Rootes family, but privately and outside the Rootes Group.

This arrangement should have led to further work for Harrington, but the future for Rootes was looking gloomy, and the coachbuilder was also heading for troubling times. By the mid ’60s, Harrington Alpine production had ceased. The final Sunbeam to be converted by Harrington would be the one and only Harrington Tiger, built in January 1965.

The last of the Harrington family, Geoffrey, resigned in 1965, with the car-sales segment of the business now a part of the Robins & Day Group — incidentally, this company still trades in the UK as a chain of Peugeot dealers.

Towards the end of 1965, Harrington announced it would cease its coach-building activities in 1966 — the final product being a Grenadier coach. Following this, the Sackville Works was closed up and, sadly, much of the company’s archive material was destroyed during the closing-down period.

The Harrington name would continue in motor sales, following the Rootes empire to Renault, and then as a BMW agent until the 1980s.

John Barley, an Auckland-based insurance broker, purchased his first Sunbeam Alpine — a Series II car — when he was only 19. Subsequently, that car was sold, and it wasn’t until many years later — now married to Suzanne and self-employed — that the idea of owning another Alpine came up. After looking around, John and Suzanne eventually settled upon a Series V Alpine, bought in 1999 for $3K.

Pictured: John Barley

Now a member of the Sunbeam Car Club, John soon found himself making new friends and learning lots more about Sunbeams.

Indeed, he took up the role of Auckland club captain for nine years until 2009, serving the following three years as the club’s national president.

From a fellow club member, Ross Somervell (who sadly passed away in December 2013), John was able to borrow a copy of Chris McGovern’s excellent book, Alpine: The Classic Sunbeam. Within that book’s pages, John came across photographs of the fastback coupé Alpine that Harrington had built for the 24 Hours of Le Mans race. The Harrington Alpine that came 16th in 1961 was driven by Peter Harper and Peter Proctor. A second, more standard-looking, Harrington-modified car, driven by Peter Jopp and Paddy Hopkirk, was a DNF in the same race.

John instantly fell in love and, along with Suzanne, decided he just had to own one.

Sydney Sunbeam

He began to look up and talk to overseas Harrington owners, determined to learn more about these rare sports cars and see if he could find one for sale — not an easy task, bearing in mind that only a very small number of these bespoke Alpines were ever built.

However, John’s perseverance paid off when he contacted the owner of a Harrington Le Mans in Australia. During their chat, John found out that the car was for sale — the asking price being $30K. Alas, this was out of John’s budget, so his search continued.

Then, out of the blue, a few weeks later, the Australian Harrington owner got back in touch with John and confirmed his car had been sold to a chap who already owned a tired and unrestored Le Mans. Apparently, the car was parked up in this person’s backyard somewhere in Sydney — but, with his contact details to hand, John was soon on the phone to Australia. He says the man was rather rude and didn’t appear to have any desire to sell, finishing their conversation by remarking that if John was still interested, he’d call back a week later. Sure enough, the following week — just before that year’s Easter weekend — John found himself talking to the Harrington owner again. He was now told that the car would be viewable in Sydney over the weekend, and this would be John’s one and only chance to check it out and make an offer on it.

After discussing it with Suzanne, John bought two air tickets to Sydney, and the couple flew off to check out the Harrington.

When they eventually stood in front of the car, they knew that a lot of work would be required on the Le Mans. A mishmash of all sorts of colours, and with a badly bent and damaged front-end, the Harrington looked tired and neglected. However, John’s dream to own one of these special cars remained strong. When the owner asked him what he thought it was worth, John came up with the figure of $5K. The owner was expecting $10K, a sum John believed was too high taking into consideration the car’s sad condition. After further negotiations, a price of $6K was agreed upon and — exactly a year after they had acquired their SV Alpine — John and Suzanne became the proud owners of a rather dilapidated Harrington Le Mans.

Show-car origins

The Harrington was subsequently shipped to New Zealand through one of John’s clients. The rebuild of the car began eight years ago — and, as John admits, it’s still a work in progress.

First, the car was stripped back to a bare shell. During this process, John discovered its original ownership papers. Interestingly, this particular Le Mans proved to have been one of four cars sent to the US as show cars — the words ‘Show Car’ still visible on the rear bulkhead when the car’s trim was removed. At that time, the Harrington was a LHD car finished in Carnival Red and wearing a set of wire wheels — and the first owner was Lloyd George III of Beverly Hills.

As the car’s nose was so badly bent out of shape, a new nose — up to the middle of the front wheel arches — from a standard Sunbeam Alpine was welded into place.

During the restoration process, John put the car on steel disc wheels — having no desire to repeat the problems he’d experienced with the wire wheels on his Alpine II — and he replaced the original red paint with a coat of Aston Martin green.

The car’s fibreglass panels were refinished by an experienced boat-builder, while new carpets and trim items were also sorted. John had the original seats reupholstered, but, due to the simple fact he is a tall bloke — well over 1.8 metres — he found the driving position was just too high and cramped for him. Luckily, a panelbeater friend had a solution, fitting a set of seats from a Toyota MR2. These allowed John a much more comfortable driving position, although, as yet, these donor seats have not been reupholstered to match the rest of the car’s interior.

Engine talk

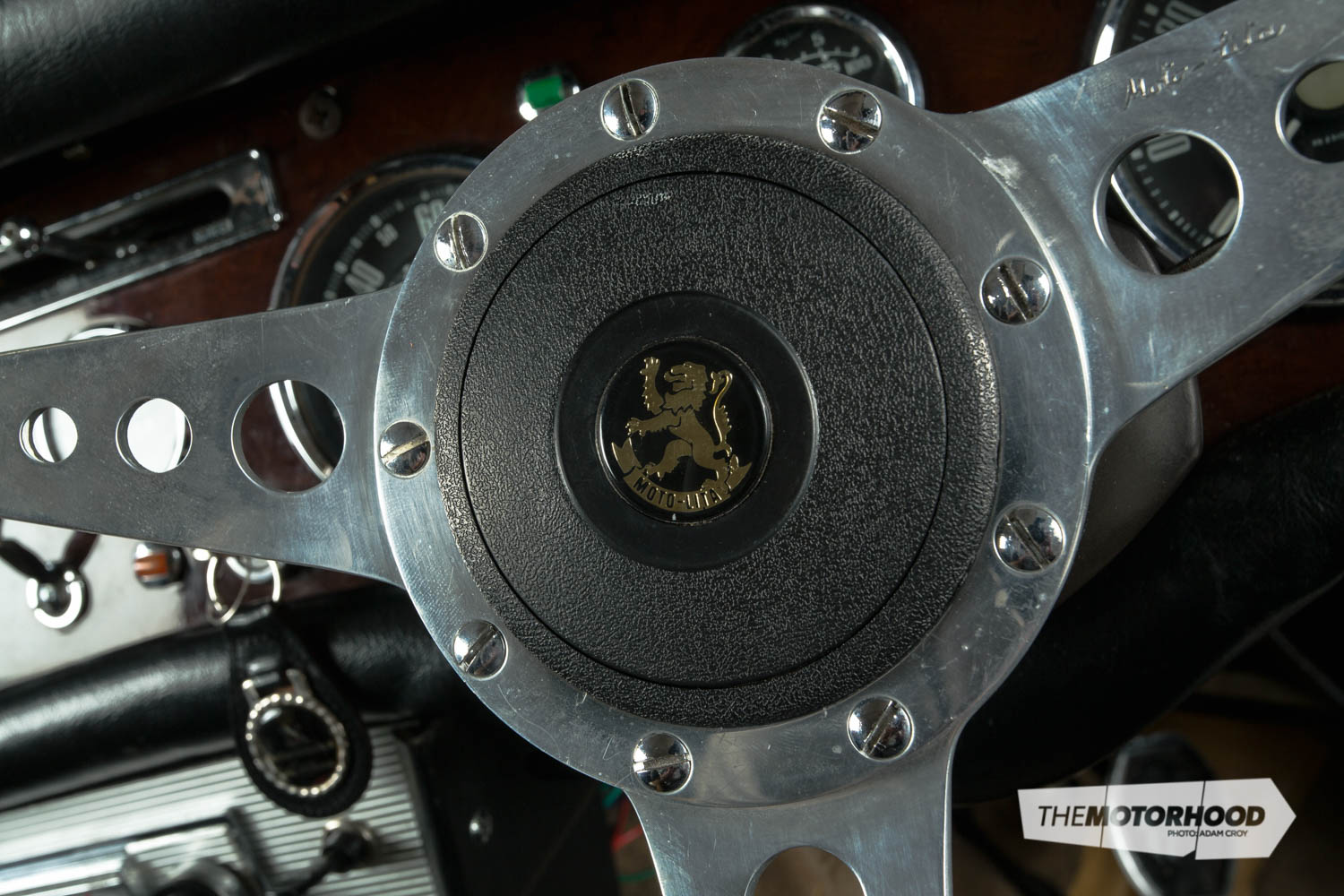

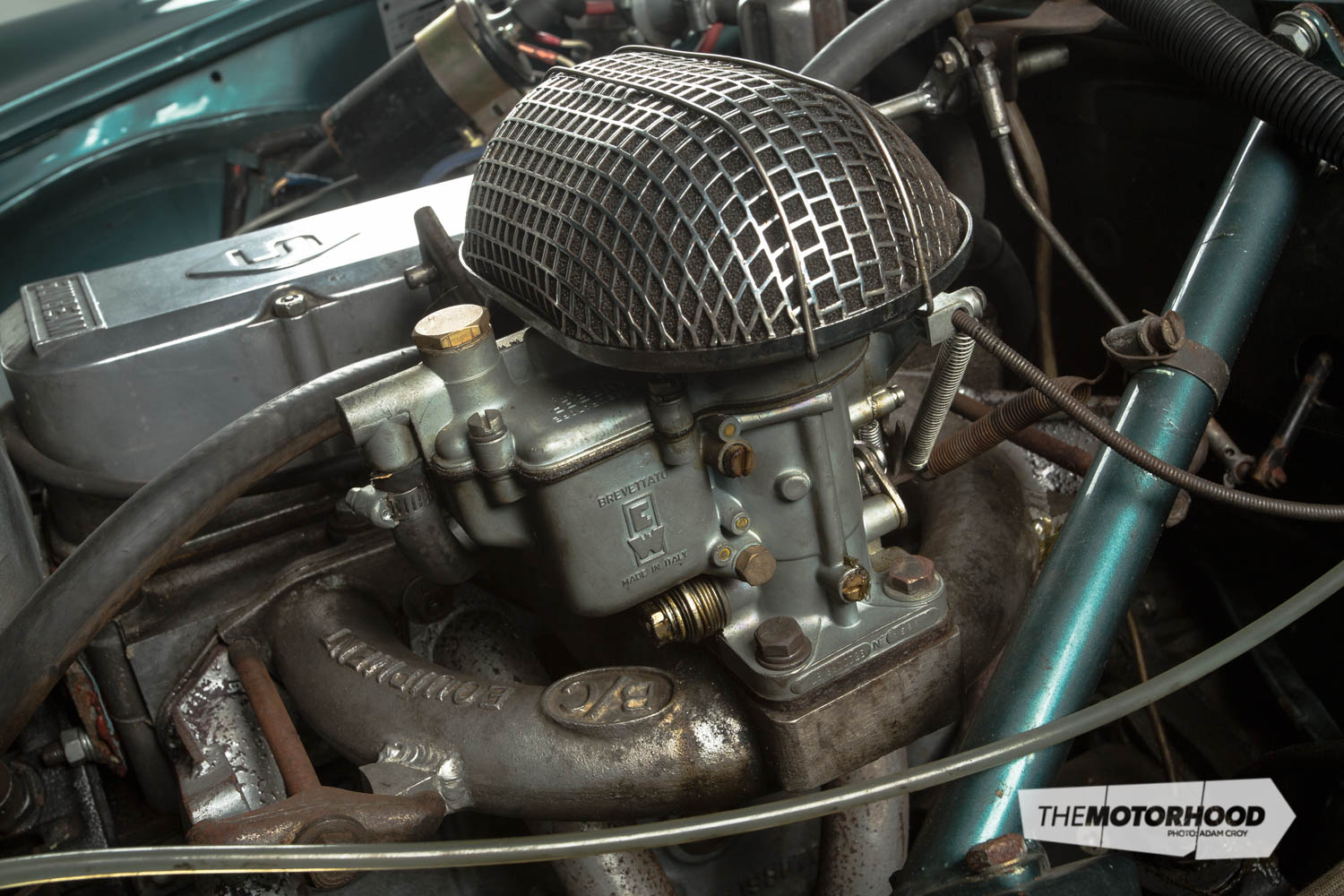

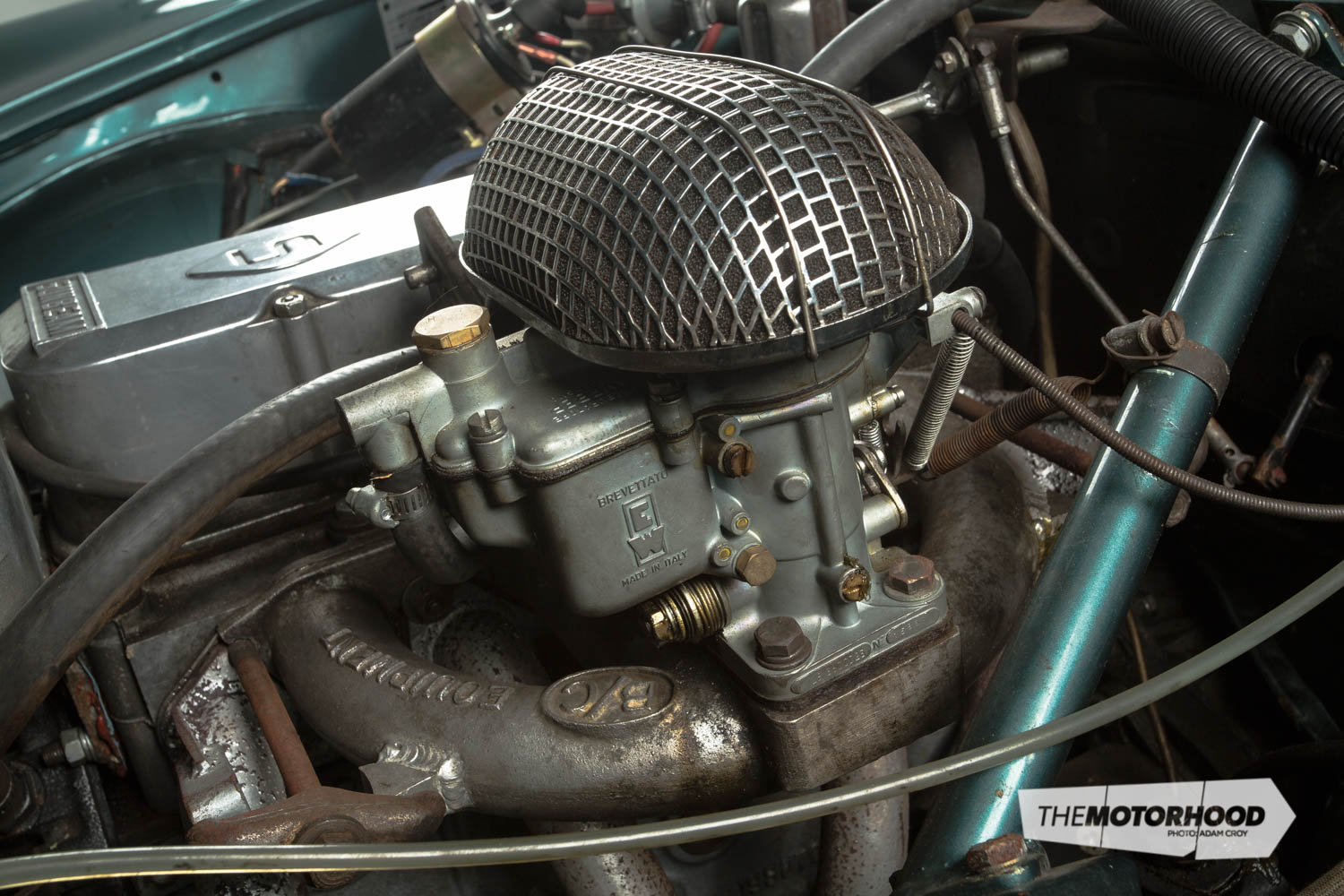

Back in the ’60s, Harrington-converted Alpines were available with a series of engine-tuning options — all carried out by George Hartwell Ltd of Bournemouth, UK. The Le Mans cars were more of a production line car than previous, or later, Harrington Alpines and, as such, had a more standard specification. This included Stage II engine tuning — which entailed the engine being ported and polished and the fitment of modified carburettors. A stronger clutch was balanced together with the crankshaft and camshaft for a power output of 78kW (104bhp). Further up the tuning chart, lightened flywheels, compression increases, and twin side-draught Weber carburettors were also available.

The engine in John’s Le Mans is still the original 1592cc ported-and-polished four-banger, although it now gulps fuel through a single twin-choke downdraught Weber carburettor — a simpler set-up than the original twin Zeniths, and a good deal less expensive than a pair of twin-choke side-draught Webers.

Following a rebuild of the car’s engine, gearbox, and suspension, John finally reached the point when he could return the Harrington to the road — although this would prove troublesome, with the engine having to be removed and refitted no less than three times before everything was working correctly.

The motor was pulled out three times to get things working correctly, but, with everything squared away, John and Suzanne were soon able to enjoy driving around in the Le Mans. One interesting tweak involved recalibrating the car’s original speedometer — Auckland Speedometer Services altering the gauge so that when it reads 70mph the car’s actual speed is 70kph — very clever.

The only example of a Harrington Alpine currently in New Zealand — like the Dove GTR4A featured in issue 283 of New Zealand Classic Car magazine (also a Harrington-built car) — John’s Sunbeam is a genuinely rare and special classic.

1963 Sunbeam Harrington Le Mans

- Engine: In-line four

- Capacity: 1592cc

- Bore/stroke: 79×76.2mm

- Valves: OHV

- Comp. ratio: 9.5:1

- Max power: 78kW at 6000rpm

- Max torque: 142Nm at 4500rpm

- Fuel system: Weber downdraught carburettor

- Transmission: Four-speed manual, OD

- Suspension F/R: Independent by coil springs and shock absorbers; beam axle and leaf springs

- Steering: Recirculating ball

- Brakes F/R: Disc; drum

Dimensions:

- Overall length: 3942mm

- Width: 1537mm

- Height: 1346mm

- Wheelbase: 2184mm

- Kerb weight: 990kg

Performance:

- Max speed: 170kph

- 0–96.5kph: 12.2 seconds

- Standing quarter-mile: 19.3 seconds

- Economy: 11.3 litres/100km (25mpg)

Production: 1961–1963 — 250