data-animation-override>

“From sheep fence to replica 1920s speedster, this Chevrolet is a moving tribute to the man who was probably America’s most unfortunate motor-industry pioneer”

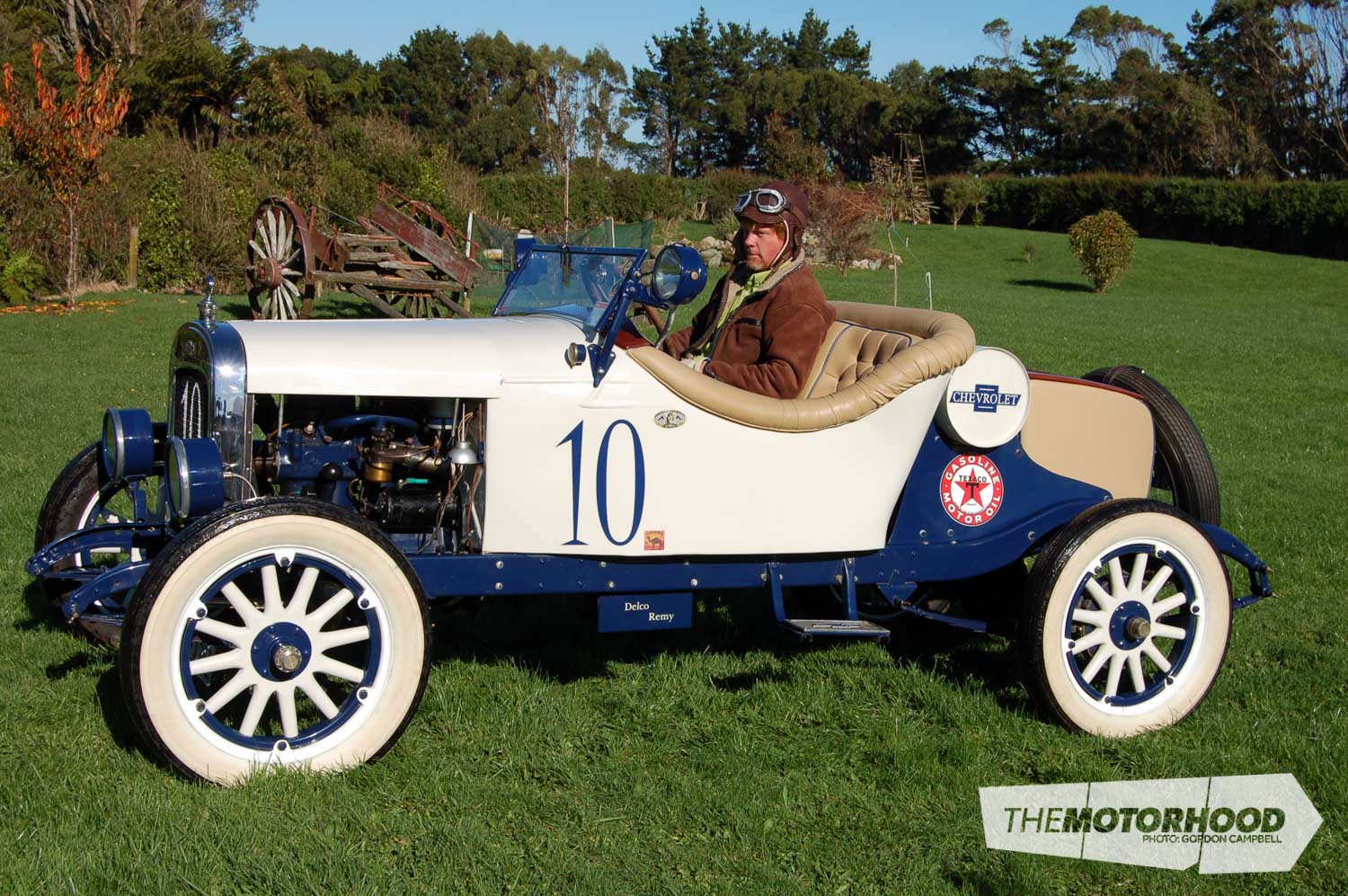

When Nigel Fraser visited one of his father’s friends in Waitara, near New Plymouth, he spotted an old chassis propped up in a fence to stop sheep escaping. With several vintage Chevrolet restorations behind him, Nigel recognized the make and approximate year of the chassis, and had to have it. He’d immediately seen the basis for the open-wheel speedster he had long wanted to build.

Hunting and gathering

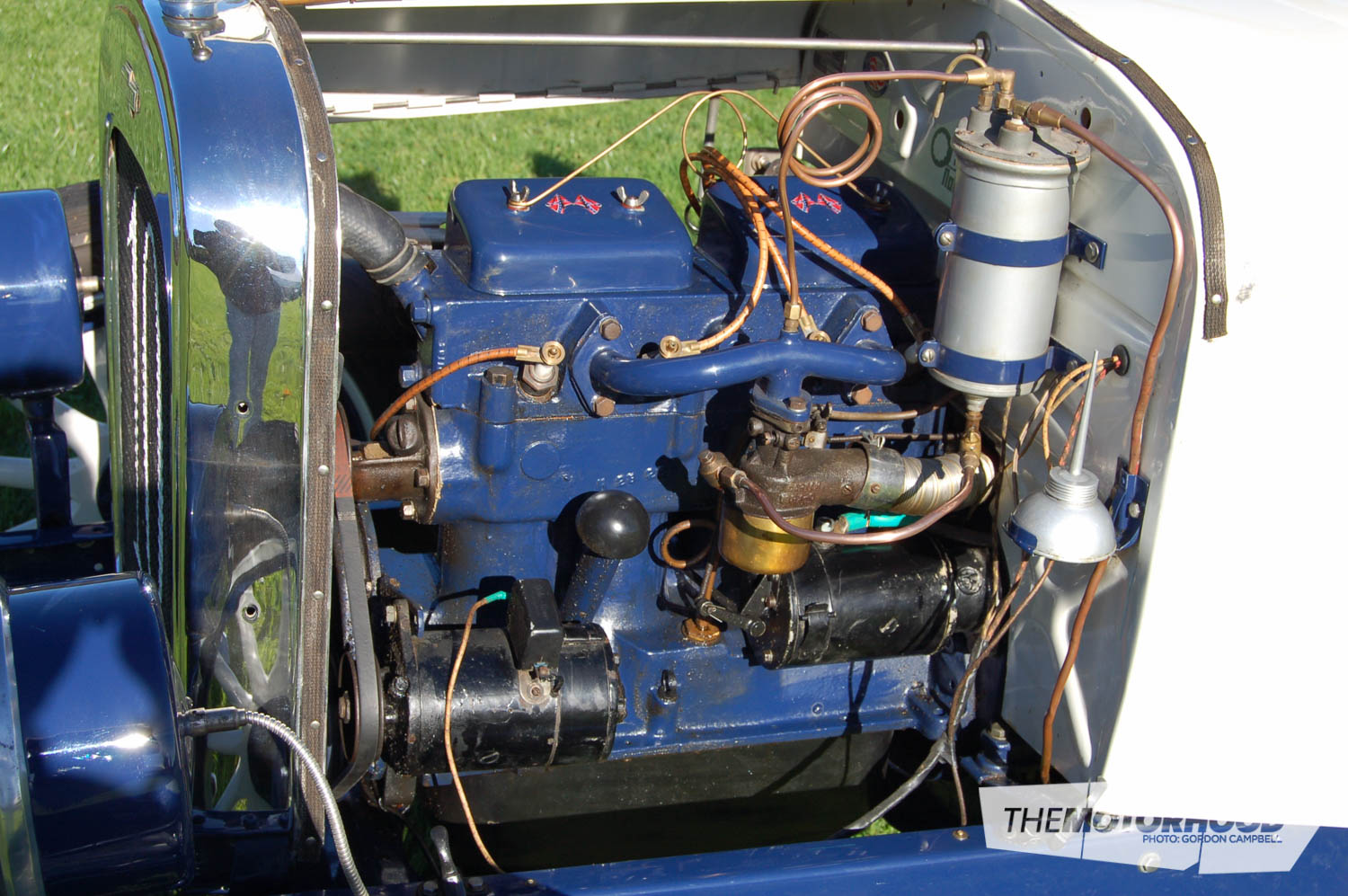

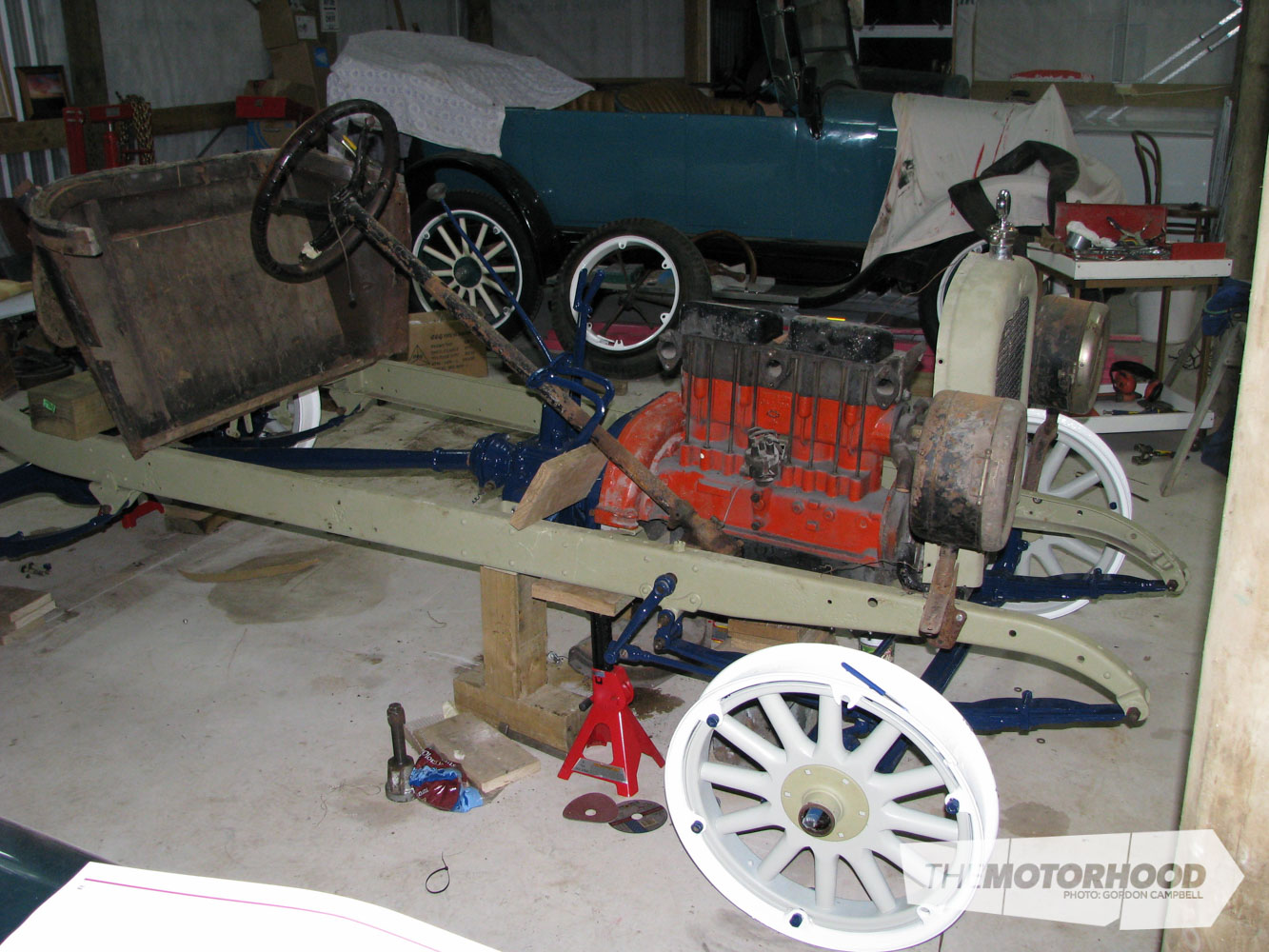

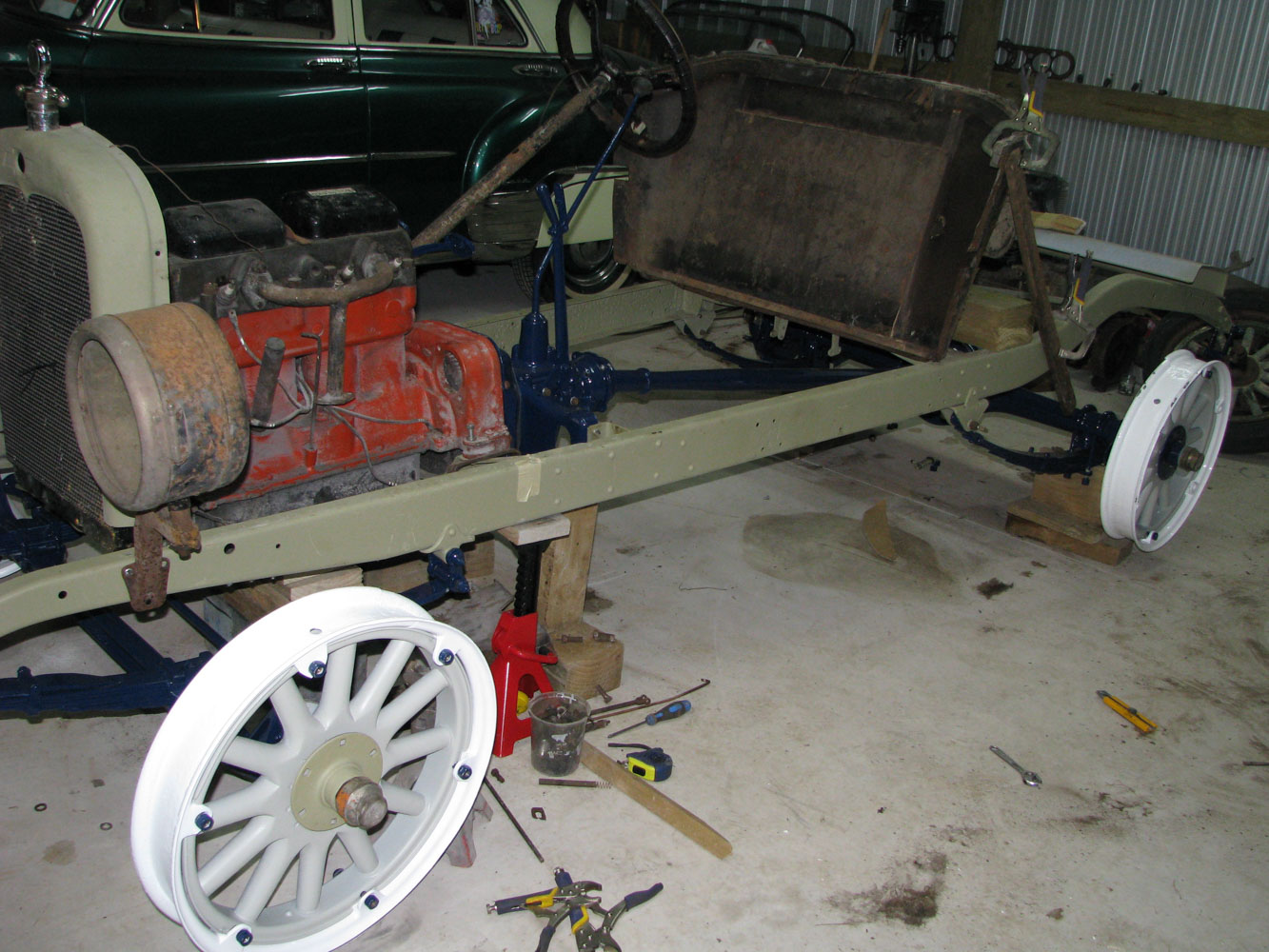

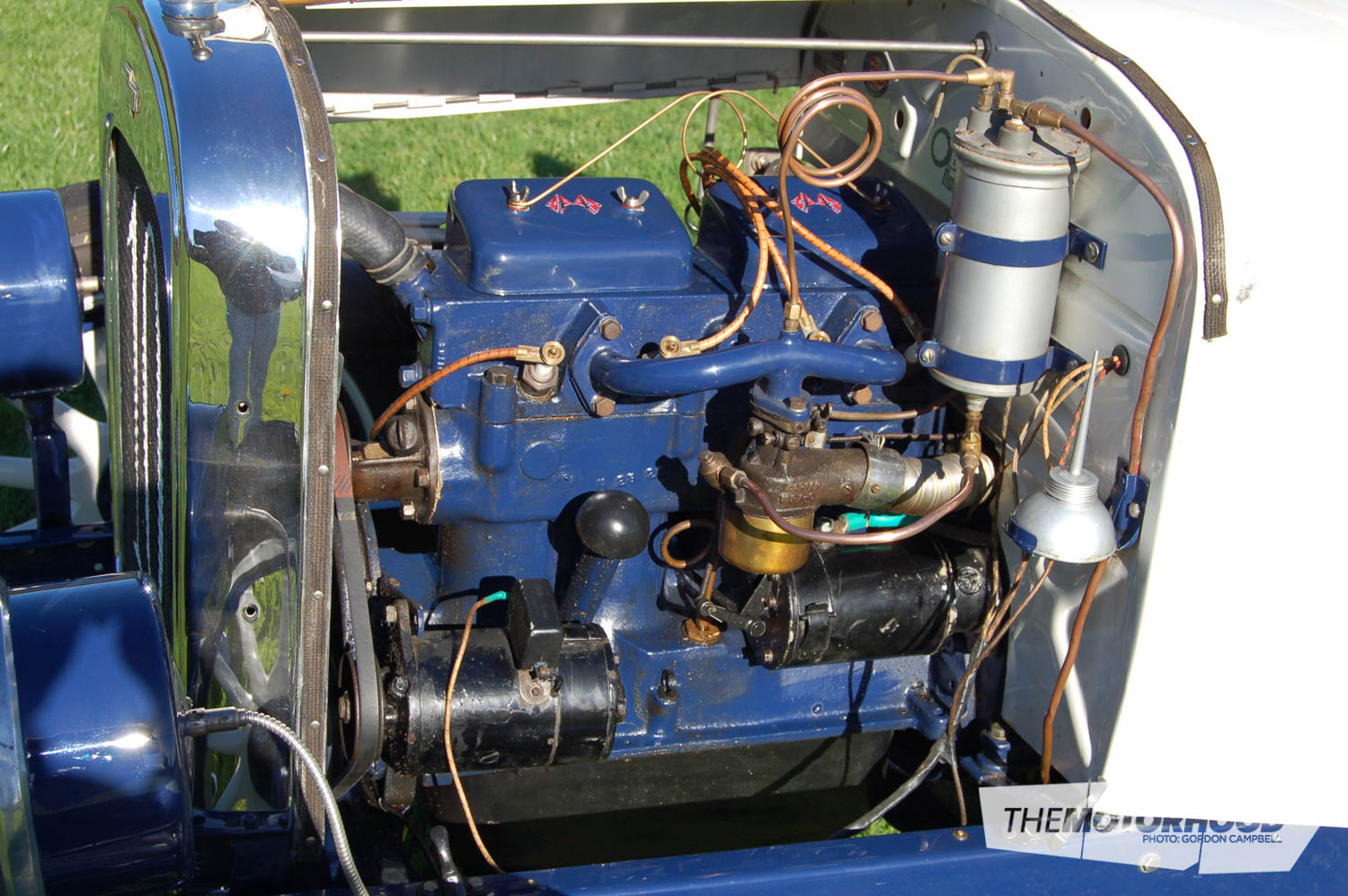

Back home in Opunake, on Taranaki’s Surf Highway, Nigel put the chassis away and began gathering up parts. A differential was rescued from his father’s junk shed, and an engine from a friend in Levin. Nigel found a cross-flow cylinder head from a 1916 Oldsmobile, which bolted straight on to the block and would significantly improve breathing over the standard head. He bought a gearbox for $30, and reconditioned it by changing the oil.

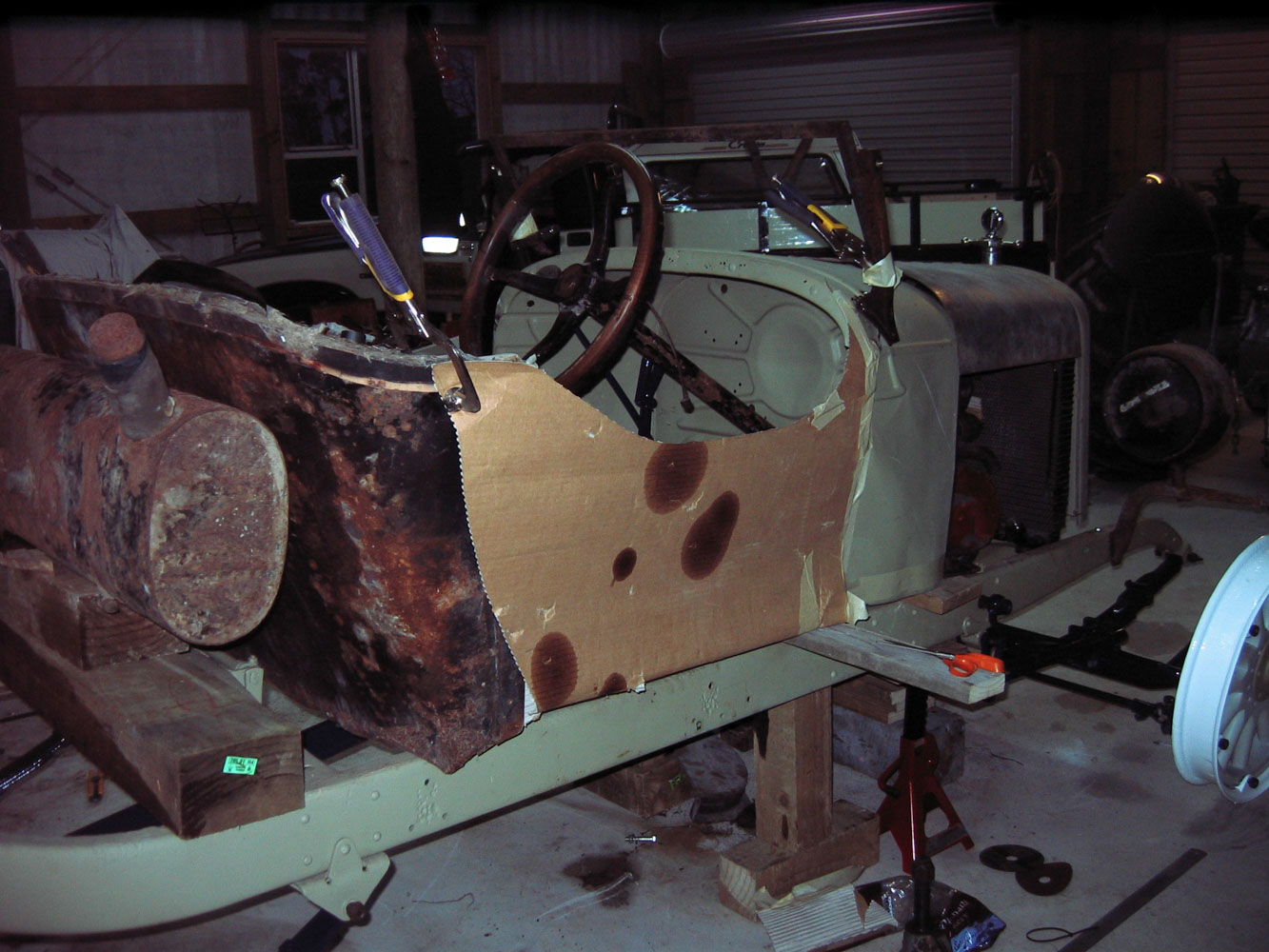

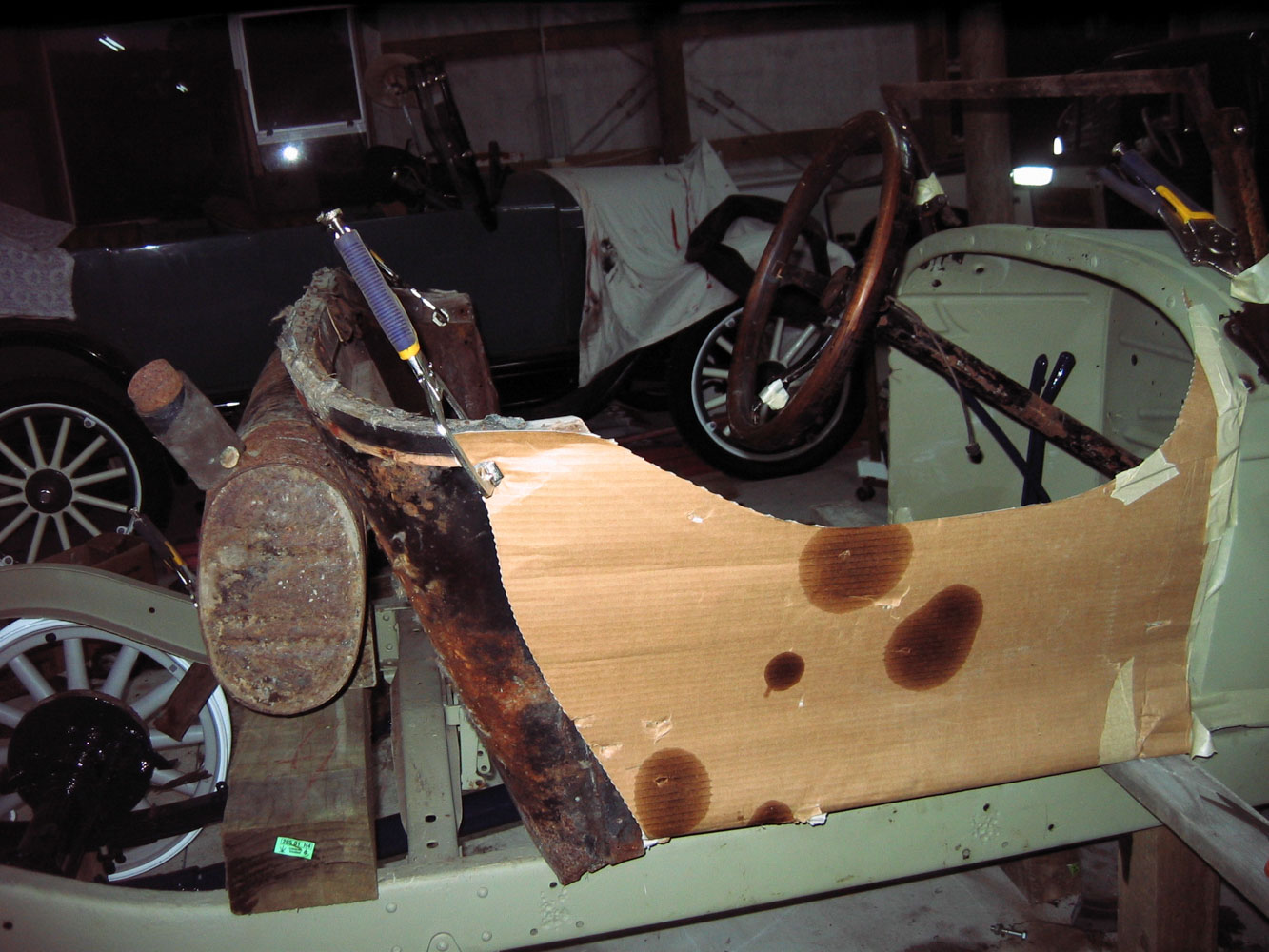

After a year of collecting parts, followed by cleaning, painting and test assembling, the rolling chassis and running gear were complete. It was time to hand it over to his good friend and fellow vintage Chevrolet enthusiast, Neil Carter.

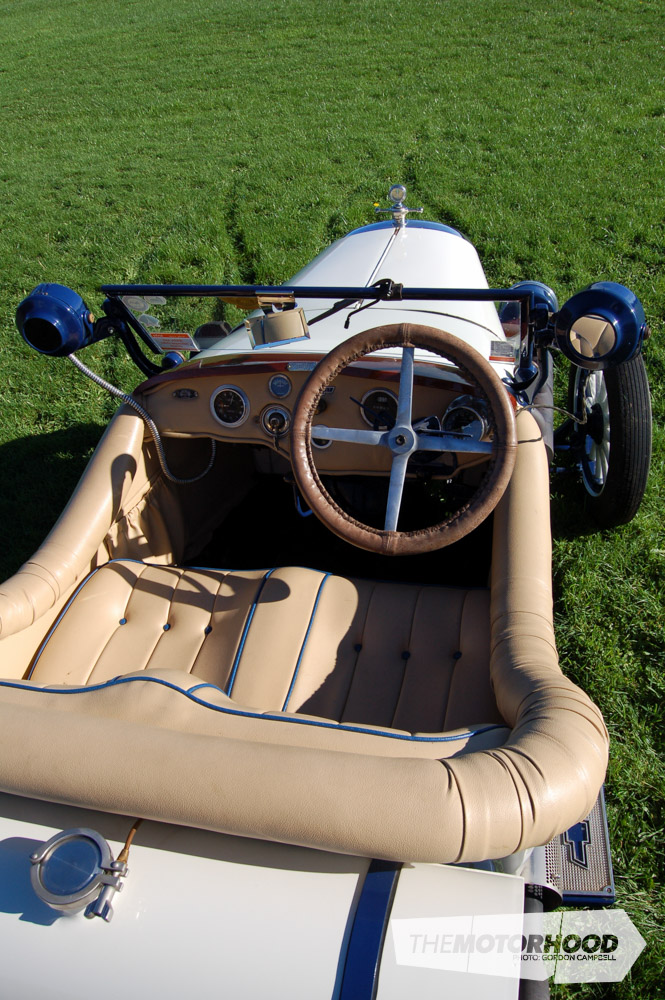

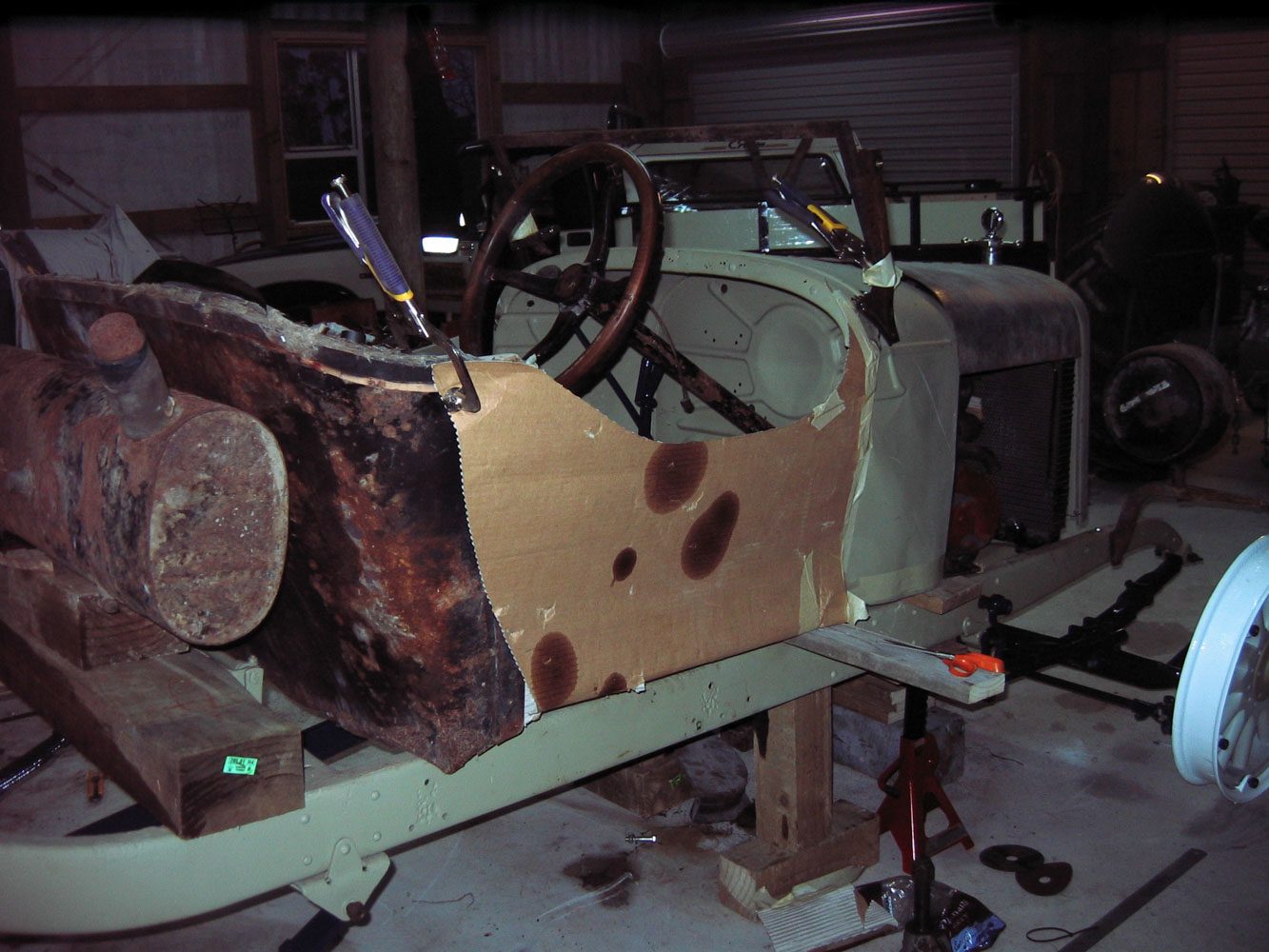

Neil’s business, Furniture and Design of Normanby, South Taranaki, specializes in vintage-car timber work, and Neil has a well-earned reputation as an artist in automotive wood. Given some of the special cars Neil has reframed, the Speedster’s minimal framing and turtle-deck boot were hardly a challenge, so it was soon back for Nigel’s team to create the panelling. Nigel’s business — Classic Auto Repaints, based in Opunake — does exactly what its name suggests, but much more. He is a trade-qualified car painter who is also skilled at panel repairs and mechanical work.

Nigel built the fuel tank while Andrew Corkill, one of his talented apprentices, shaped the body, then painted it and the tank. Nigel took a while to decide what the colour scheme should be. It wasn’t actually that hard — he had a very clear mental picture from the start of how the finished car would look, but he wanted the shades to be exactly right. His other very capable apprentice, Amber Brown, pointed out that he’d chosen the colours of Chevrolet’s ‘bow tie’ emblem.

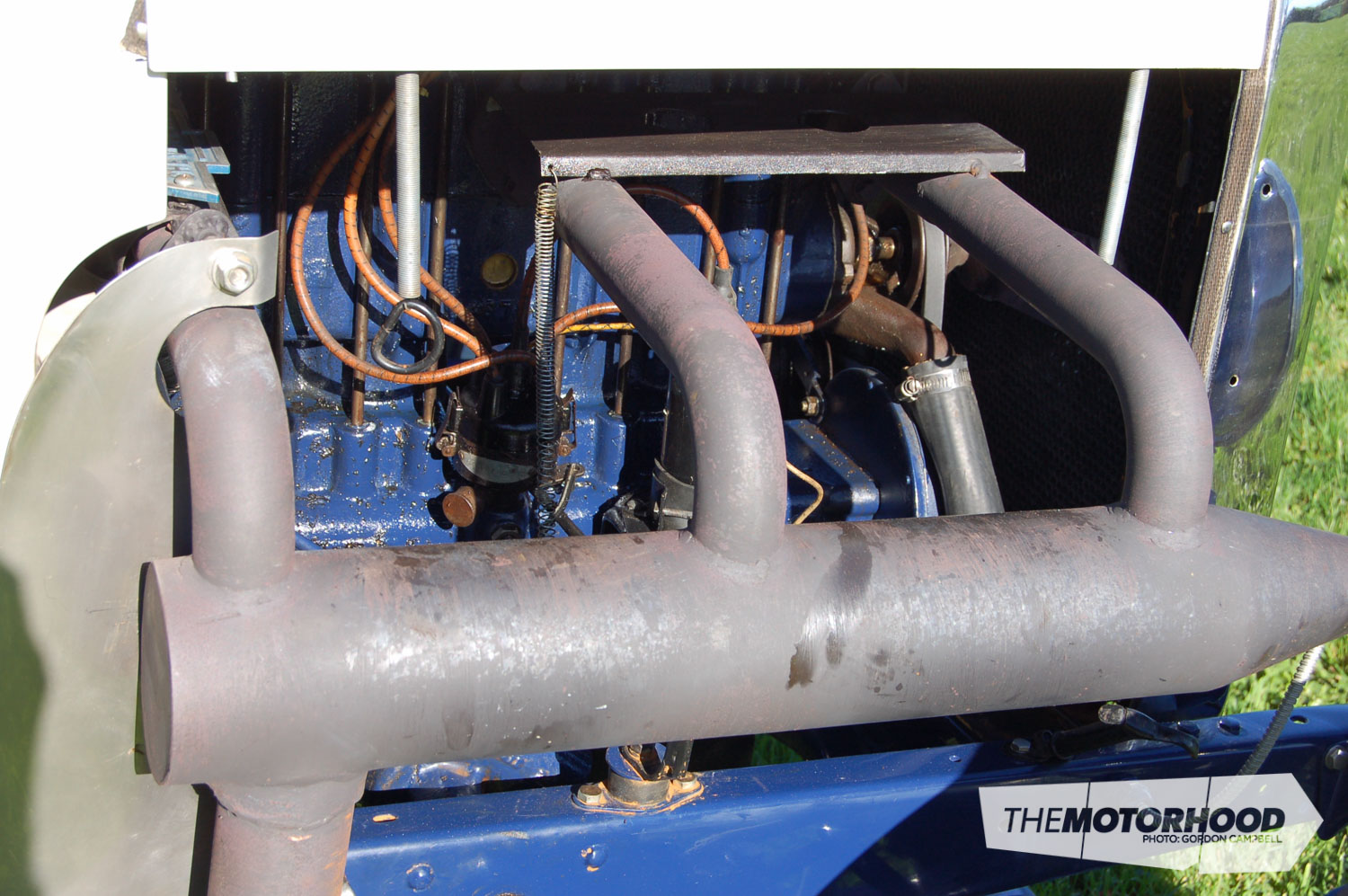

Kevin Lowe, another exceptionally clever Opunake local, helped with the wiring, and made up the pipework and brass fittings. The cockpit trimming and sides of the turtle deck were stitched by a local upholsterer. The exhaust system was almost completely owner built, and Nigel wanted sharp, agricultural-looking bends to replicate how exhaust systems generally looked in the 1920s.

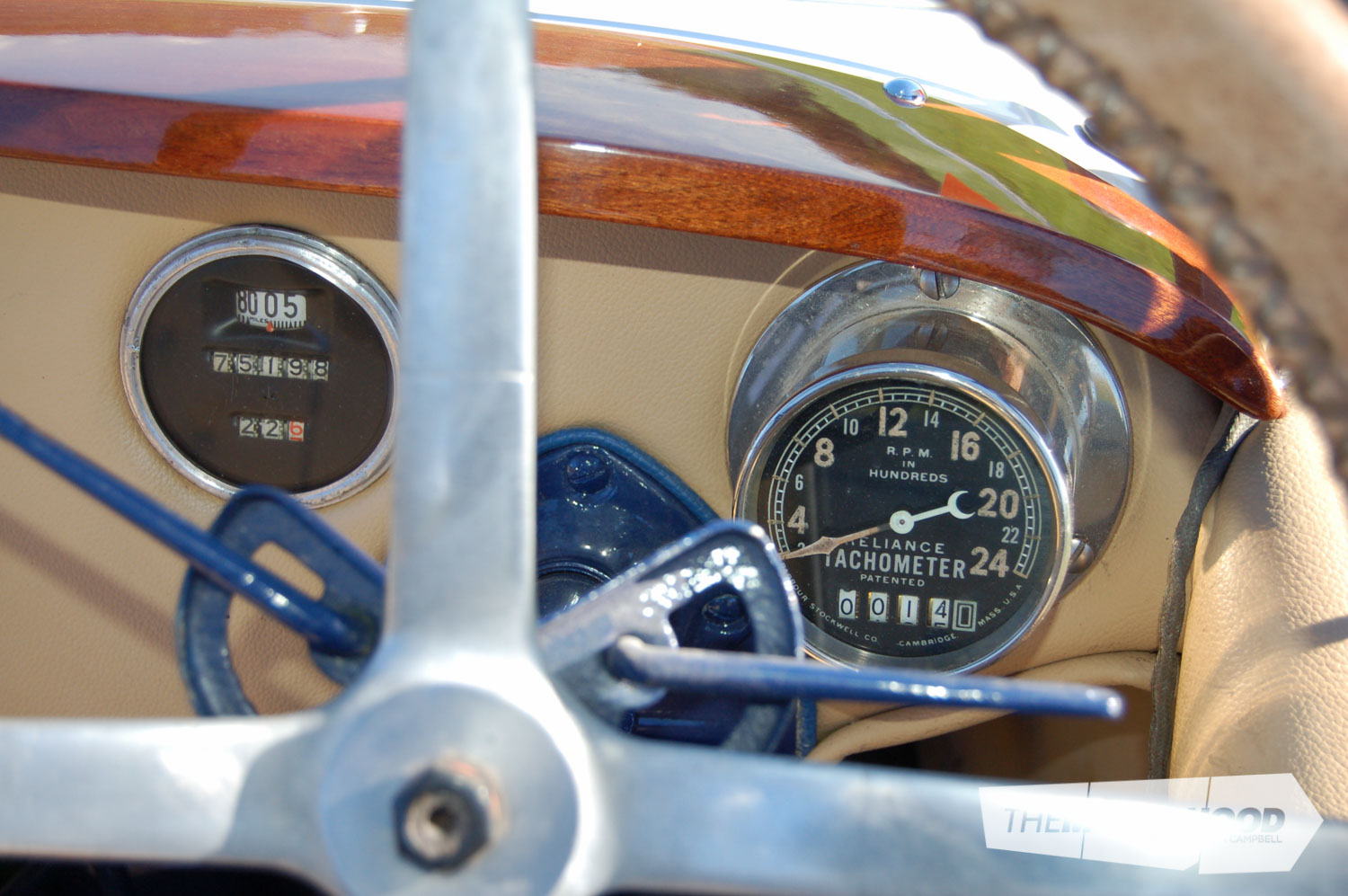

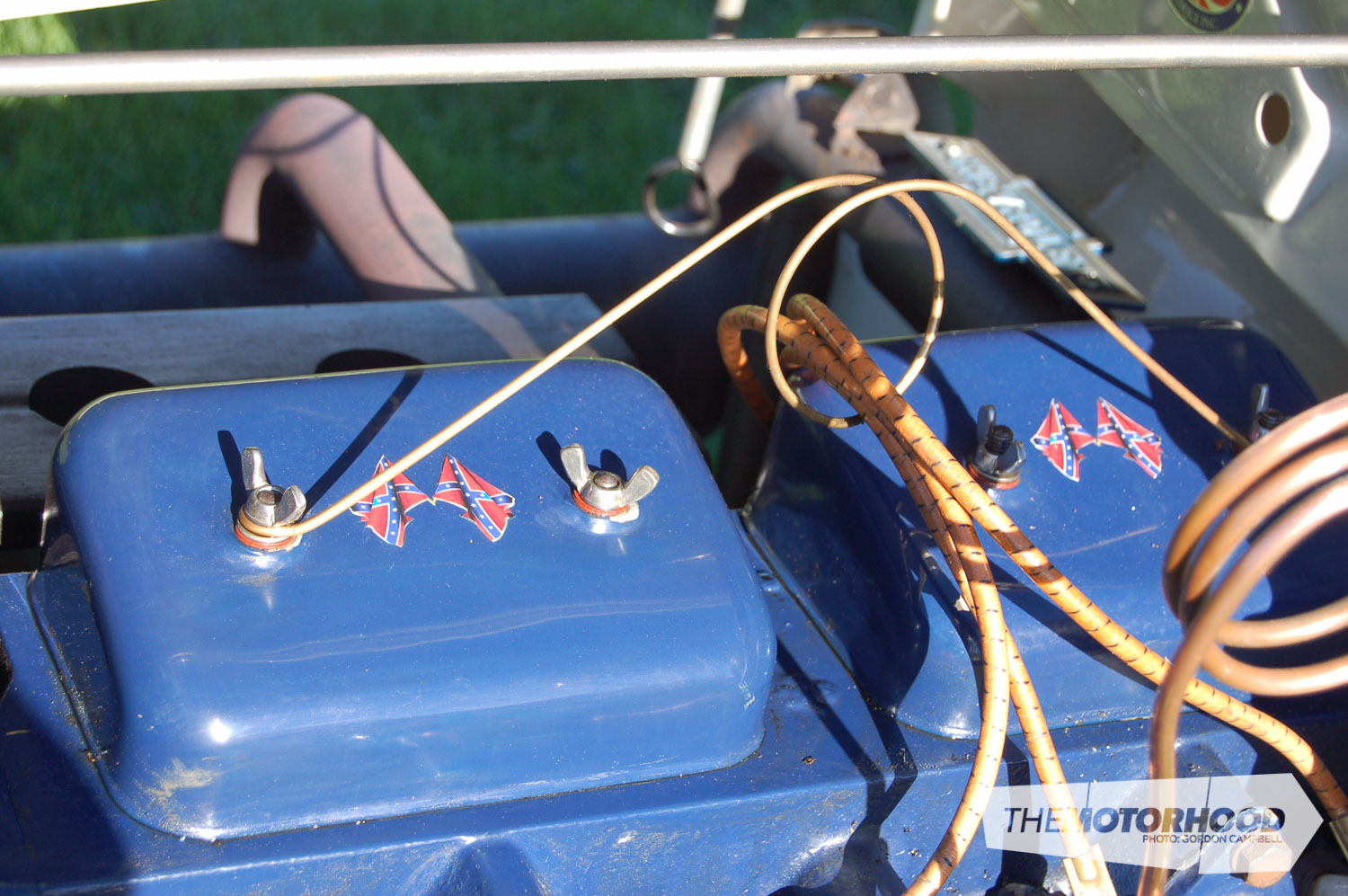

Many detail features finished off a stunning car that attracts a great deal of attention. Large spotlights, one of which doubles as a rear-view mirror, a full set of gauges — including a rare and prized tachometer that reads up to 2400rpm — and a few appropriate decals are just a few of the details Nigel has added.

He bought the chassis in 2006, and the car was completed by mid 2013. His wife, Michele, suggested that having it complied and registered could be his Christmas present, and it was all legal on Christmas Eve. Initially a little concerned when a young inspector approached the car looking for a door handle, Nigel was relieved when a rather more mature inspector took over. The Chevrolet passed its inspection without incident.

Pace yourself

Riding in the Speedster is like riding a motorcycle without leaning into corners. You’re in the open air, exposed to the elements and all manner of country smells as you go, while the valve gear chatters happily away. You can look down at the front wheel and suspension, and watch them working, or look into the footwell and see what the pedals actually do.

At a standstill, you can watch the exposed pushrods operating, which is part of the appealing mechanical-ness of this car. It’s an interesting mix of technologies — overhead valves were relatively rare in the late ’20s, and yet the engine has exposed pushrods. The ‘lucky-dip lubrication’, as Nigel describes it, obviously works, going by the small puddles that appear under the car at a standstill. You can imagine how oil slicks took over from horse droppings as street hazards in the 1920s.

Everything happens at a leisurely pace — gear changes are accomplished deliberately, with no guarantee of the audible results, while speed becomes a relative concept. Mind you, the torquey 2.8-litre four-cylinder engine makes gear changes infrequent as it goes about its work, while the light body ensures it seems more sprightly than it would be in a sedan.

Like a motorcyclist, Nigel loves winding roads where he can feel as though he’s flying along, only to look down and see 70kph registering on the speedo. Even with rear-wheel brakes only and the need to plan accordingly, it’s motoring fun at a relaxed level.

I was puzzled as to why Nigel, at a young 45 years of age, would have a fascination with vintage cars — he owns several, and until recently they were all Chevrolets. He has a 1930 sedan and a 1931 truck that doubles as his work vehicle, and also looks after his father’s 1923 Chevrolet Tourer. However, not too long ago he acquired most of a huge, cut-down 1924 Buick that he intends to build as a Kiwi version of the monster known as Brutus — a one-of-a-kind vintage racer that was built in Germany in the years directly following World War II. This beast of a car was powered by a 46-litre V12 BMW aero engine, and today is on display at the Sinsheim Museum in Germany. Nigel also owns a chassis for another Chevrolet speedster intended for Michele, and a light Chevrolet truck that will one day be that car’s transporter. He also has a rare early ’60s Ford Capri that will be resurrected in time.

Nigel can’t really explain the vintage car thing, except to say he likes stuff that’s hand forged, hand built, with rivets, wood, steel, brass, and leaf springs. He likes the fact that you really have to drive old cars, and you have to be on the ball when you’re on the road in one, with their solid axles, ‘gate hinge’ kingpins, ‘slow-me-down’ brakes, and illuminators rather than lights. He says you can’t take things too seriously when you drive vintage vehicles, with their diabolical engineering. Anything newer than about 1932 is really too modern for him, and he thinks modern cars are boring. He has owned some newer cars, having gone through an Austin A30 phase for a while, including a Mazda rotary-powered one that his father insisted he sell as soon as possible.

The Frasers believe in using their old cars. They love getting off the beaten track on adventure drives, and the more remote the road, the better. They’ve done several long trips in the truck, including an All American Truck Club tour that started in Masterton and took them to Napier, Gisborne, Lake Waikaremoana, Taupo, Raetihi, Wanganui and home again, a total of over 1600km at Easter 2014.

Their vehicles featured in the film Predicament, shot in and around Eltham, central Taranaki, a few years ago.

Fischer towers

After Nigel qualified as a car painter he headed overseas for three years. For most of that time he worked at PJ Fischer Classic Automobiles in Putney, London, an experience much better looked back on from a distance of 20 years than lived through. Peter Fischer, a German Swiss, was an amazingly frugal multi-millionaire. The staff comprised Peter, a Polish car painter, two mechanics and Nigel. Each was given one tea bag and two pairs of rubber work gloves per day. If they damaged the gloves early in the day, it was just too bad.

Nigel says that Peter behaved exactly like Basil Fawlty, throwing incredible tantrums when things weren’t going well. Once, Nigel made the mistake of suggesting that Peter should calm down before he burst a blood vessel. That just made him redder and more apoplectic and he disappeared from the premises, only to calmly return a while later as though nothing had happened.

Peter used to go to Europe on buying trips and return with up to 20 Rolls-Royces and Bentleys, the brands the business specialized in. The cars could range from the 1930s to the 1970s, and the Fischer staff would refurbish them for resale. As a consequence, Nigel got to work on some exotic cars.

One was a 1950 Bentley Continental drophead they prepared for the Louis Vuitton concours. Four months of solid work resulted in a second placing. Back at Northumberland Garage in Putney, Peter expressed his disappointment in no uncertain terms. Having put their hearts and souls into the car, his workers were no less disappointed, and Nigel pointed out that had Peter been willing to fit new tyres, or good used ones, rather than filling the cracks with black urethane and disguising it with shoe polish, they would have won.

Predictably, Peter threw a tantrum, but later admitted that Nigel was right, a gesture that amazed the other employees.

All in all it was a character building experience, and Nigel acquired valuable skills that he’s using to good effect later in life. Much more pleasant were the six months he spent working in Lyon, France, even though understanding their automotive paint systems was a challenge.

Builder and driver

Nigel is a person who thinks in pictures, a gift that allows him to see the finished article before work begins. A quiet demeanour masks a fertile imagination and passionate enthusiasm, and the Chevrolet Speedster is a product of both.

Some enthusiasts like to build vehicles rather than drive them, while others prefer driving. Nigel likes to do both. He spends countless hours building them, and then thoroughly enjoys using them as they were originally meant to be used. He’s happy to take on most aspects of car restoration. He has several projects lined up ahead of him, but they aren’t idle dreams that will never see the light of day. His skills and drive have already produced many fine vehicles, and there are more to come.

Nigel Fraser’s artistic eye for line and detail, along with a singular combination of skills, have enabled him to create a special car that evokes an age of motoring adventure long gone. It’s a fitting way to remember Louis Chevrolet.