data-animation-override>

“The plan for Keith Sinclair’s Cuda was cool first, fast second. We think you’ll agree, he nailed it”

The inspiration behind this mighty 1970 big block Hemi–powered Plymouth Cuda race car, owned by Auckland’s Keith Sinclair, began in late 1969. American racing legend Dan Gurney and his All American Racers (AAR) team had just won a lucrative contract to build and race Chrysler’s new Plymouth Cuda in the Sports Car Club of America (SCCA) Trans-Am series for 1970.

Started in 1966, by 1969 the Trans-Am series was flying high and manufacturer involvement was immense, as the pony-car market segment soared. That year saw factory-supported race teams of Ford Mustangs, Chev Camaros, Pontiac Firebirds, and AMC Javelins. Ford supported two teams, Shelby and Bud Moore, which each ran two cars, sometimes three. Mercury had raced in 1967, but the Ford hierarchy decided it didn’t want two of its brands competing against one another. The racing was intense, and, since there was no marketing value in finishing second, each factory team was expected to win, especially since there were millions of dollars of factory money on the line.

The rapid growth of the Trans-Am series prompted Nascar owner Bill France to formulate his own version, which began in 1968 and used virtually the same set of regulations. Racing predominantly on oval speedway tracks, it was initially called Nascar Grand Touring before being renamed Nascar Grand American. It exists to this day, now called Nascar Nationwide series.

By 1969, one manufacturer was notable for its absence. Chrysler was missing out, and knew it. So it stepped up and funded a multimillion-dollar two-pronged attack on the 1970 Trans-Am series, contracting AAR to campaign a team of Plymouth Cudas, and Autodynamics/Sam Posey a team of Dodge Challengers. AAR would run two cars, driven by Gurney and his young protégé Swede Savage, while Autodynamics would field a single car, driven by Posey.

AAR built the basic body structures and roll cages and took care of the fabrication work for both teams. It delivered three Challenger bodies to Autodynamics, and made four Cudas for itself. Each was initially supplied by Chrysler as ‘bodies in white’, meaning they were special-order bodyshells plucked straight from the assembly line before all their heavy sound deadening was added. From there, they were acid dipped. Trans-Am race cars had to be fitted with factory standard bodywork, and teams quickly learned that the acid-dipping process, which ate away at the metal, was an effective way to reduce weight while still abiding by the rules.

The Trans-Am series rules stipulated a maximum 5000cc engine size, and maximum 15×8-inch wheels. Also, for 1970, only a single four-barrel carburettor was allowed. Minimum weight was 3200 pounds (1451kg). But the cars themselves were works of art, and they were fast. Chrysler was pro-active in helping its teams to victory lane, by releasing low-volume homologation specials of the Cuda and Challenger. These both included lightweight fibreglass bonnets and rear spoilers.

The road-going Cudas were called AAR Cudas, and their bonnet incorporated a large central Naca duct, which force-fed cool air into the carburettor. The Challenger road cars were called Challenger T/As, and their fibreglass bonnet was fitted with a large snorkel, which had the same effect. The Trans-Am rules didn’t require the homologation of front spoilers; they allowed any flat-pane spoiler to be constructed by the race teams, and most went with either an alloy or fibreglass item with brake duct holes on each side plumbed with cooling hoses to aid brake temperatures.

Chrysler stipulated that Autodynamics paint its cars Limelight Green, a colour Posey hated. So he added a bunch of black-out areas to cover up the bright green paint, including the roof and the bonnet snorkel, plus he added bold stripes down each side. Interestingly, AAR had the freedom to paint its cars any colour it wanted, so opted for a dark metallic navy blue, with huge white numbers on the doors. Gurney wore No. 48, Savage No. 42. The cars were also fitted with lightweight magnesium Minilite wheels wrapped in Goodyear Blue Streak cross-ply racing tyres. As well as funding from Chrysler, and several smaller sponsors, the AAR Cudas had support from Mattel’s Hot Wheels brand.

The 1970 Trans-Am series began at Laguna Seca in April. After two rounds, AAR had just a single fourth place finish for Savage to show for its efforts. The cars were fast but fragile, and for it to fast-track its way to success when every other manufacturer had years of involvement was always going to be a big ask. By round three, it was down to a single-car programme, as Chrysler began getting cold feet and decided to reduce its funding.

By 1970, pony car and muscle car sales were starting to slump, as insurance and fuel costs skyrocketed, and America’s youth began focusing on other automotive interests, such as the fast-growing custom van craze. Gurney stepped aside as driver, allowing the hugely talented Savage to campaign the single Cuda throughout much of the season. Initially, he took over Gurney’s No. 48 car, but wrote this off in practice, leaving the team to scramble to get the back-up car sorted.

As the 1970 series neared its end, neither AAR nor Autodynamics had scored a race win, and they were coming under increasing pressure from Chrysler. Despite Savage collecting a spate of pole positions, the Cuda often proved unreliable in the races. With two rounds remaining, Gurney made the decision to get back behind the wheel of a newly completed second Cuda, as it now became evident that AAR’s biggest rival was Autodynamics — rumours were circulating that Chrysler would support only one team for 1971.

Autodynamics also entered a second Challenger for the last two races, bringing in Ronnie Bucknum to drive it. As it turned out, Dodge beat Plymouth in the manufacturers’ championship, finishing fourth while Plymouth was fifth. But it didn’t matter. Neither AAR nor Autodynamics reached victory lane, and, at season’s end, Chrysler pulled the pin on its brief foray into the Trans-Am series, electing to withdraw completely. In fact, Ford, Chevrolet, and Pontiac all bailed as well, leaving AMC to continue as the only factory team in 1971.

At the conclusion of the season, the two remaining AAR Cuda race cars were sold — the fourth body was never completed as a race car. The Savage car went to Goodyear for use as a promotional vehicle and tyre tester, while the Gurney car was sent to Chrysler France, where it raced from 1971 in both the French and European Touring Car Championships, headed and driven by Henri Chemin. Europe and the United Kingdom raced to FIA Group2 rules, which allowed greater freedoms than those of the Trans-Am, including bigger motors and wider wheels. So, to tackle the high-speed European race tracks, the ex-Gurney AAR Cuda was eventually fitted with a mighty 426ci big-block Hemi motor and repainted red and white.

Over the next few years, the Cuda changed hands a couple of times, was repainted again in an eye-catching yellow and black colour scheme, and was fitted with significantly wider wheels. It attempted to qualify for the 1975 24 Hours of Le Mans race, but failed to do so, despite being rumoured to have reached 190mph on the Mulsanne straight!

Eventually, an American enthusiast tracked down the Cuda, shipped it back to the US, and had it restored back to its AAR / Dan Gurney guise, complete with five-litre motor and eight-inch-wide wheels. It now races with the Historic Trans Am group, in which the Swede Savage Cuda also competes as does the Sam Posey Challenger.

Fast forward in time to January 2013, and the New Zealand Festival of Motor Racing (NZFMR) held at Hamptons Downs. The NZFMR has quickly established itself as the premier historic racing event in New Zealand, and a mainstay of the event has been the newly established Historic Muscle Cars for pre 1977 period-correct racing sedans. HMC was created in 2011 for muscle car enthusiasts who wanted to build and race period-correct big-bore sedans in a low-pressure, fun environment. HMC rules require cars be fitted with factory-standard all-steel bodywork, cast-iron cylinder heads, 15-inch-diameter wheels with Goodyear Blue Streak or Hoosier cross-ply tyres, and numerous other requirements that were enforced in period.

Attending this event were Keith Sinclair, his son Andrew, and their close friend Mike “Bic” Anderson. The Sinclair family has a long history in powerboat racing, but Andrew, his wife Mandy, and younger brother Paul all took up car racing in the mid 2000s, competing in a fleet of Commodores in the Central Muscle Cars series, as did Mandy’s older brother Paul, with an XA Falcon. In recent years, they’ve drastically reduced their racing commitments, so it came as a surprise when Keith, now retired from running the family business, and having never raced cars before, suddenly displayed a strong desire to get involved with Historic Muscle Cars.

Bic takes up the story: “Keith, Andrew, and I were shooting the shit at the festival, when Keith mentioned he’d probably like to run around with these other cool old ’70s Trans Am–type cars. Andrew and I advised him there were two four-letter words that meant ‘cool’; they were ‘Hemi’ and ‘Cuda’ — not like anything else out there, enough grunt to smoke the tyres in any gear, and a tribute to one of the greatest racers of the ’60s and ’70s: Dan Gurney.”

That the car pictured here was transformed from a rough shell, located in the rust belt of Illinois, to the incredible, show-quality machine that made its race debut just 18 months later, is largely the result of the work ethic and commitment of its builder, Bic. Bic is the owner of Sonic Race & Machine, in Tauranga, and several of his incredible builds have been featured in NZV8.

Having settled on building a Cuda, the first step was trying to source a donor. “Keith and Andrew settled on the No. 48 Hot Wheels livery so I started the hunt for a Cuda,” explains Bic. “The first one I found, we paid for and had the shipper ready to collect it, and the dickhead backed out of the sale! So, after another hunt around, I found one in Illinois. It wasn’t the dry-state car I’d have liked, but Keith was in a hurry and decided that, rather than buy one that looked fine, and pay good money for it only to discover when it was acid dipped that it was a rust bucket, it was better to have an honest car, known rust and all.

“It arrived and I got into it in May 2013, stripped and soda blasted it first. We’d already ordered quarter panels and a boot floor, knowing from the pics we’d need them, and now that it was bare we could order the balance of the parts needed.”

Steve Noyer and the guys at Moselle Panel and Paint were tasked with the job of cutting away the rusty panels and fitting the new sheet metal. While the Cuda would be finished in the colour scheme of the AAR machines that contested the 1970 Trans-Am, it’d be powered by a massive Hemi motor, just as Gurney’s car was when it raced in Europe. It’s a 426ci motor taken out to 465ci. Therefore, while not being built as a typical replica that freezes in time a specific moment in history, the car would be more of a timeline replica, picking out all the best bits of the Gurney car over several years of its career.

While the mighty Chrysler Hemi motor enjoyed huge success for many years in both drag racing and Nascar and USAC stock car racing, its participation in circuit racing was almost non-existent. Really, it was considered too big and heavy, its power advantages being more than offset by its weight handicap. In the case of Keith’s Cuda, Bic recognized the importance of making the car well balanced. After all, Keith had never driven a race car before, and, with this monster, he was jumping right in at the deep end! So, to help offset the massive chunk of lead sitting over the front axle, Bic opted for a heavy Dana rear end as opposed to a nine-inch. With Keith bolted in, total weight comes to 1720kg, and Keith isn’t a big guy.

But Historic Muscle Cars is not a race series. There is no championship; there are no rewards for winning races. It’s all about the cars and the coolness factor, and that is where Keith and Bic really wanted to score.

“If the car had a hot little small block in there, it would actually be faster,” explains Bic, “maybe not in a straight line, but in overall lap times. But Keith was prepared to sacrifice ultimate car speed for coolness, so that was the goal: cool first, fast second.”

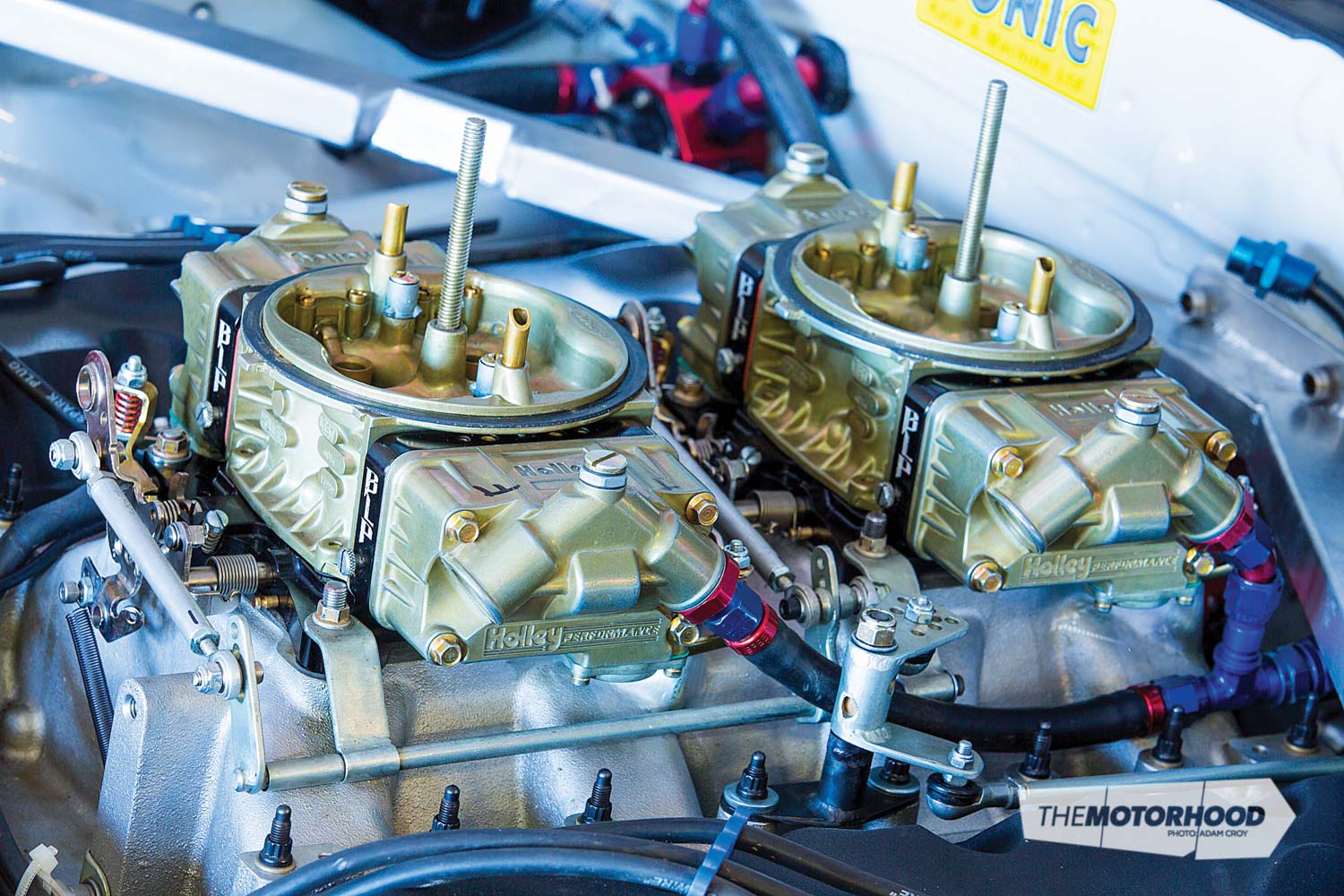

While heavy, at more than 700hp the Cuda is probably the most powerful car in HMC, despite the requirement to fit the standard AAR factory bonnet, which meant a tall high-rise inlet manifold couldn’t be used.

“We used a period Hemi ‘Marine’ dual four-barrel manifold,” explains Bic. “We modified it and rotated the carbs for maximum bonnet clearance. So it now clears the factory AAR hood with room for a cold air box with panel filter that is now fitted.”

To maintain reliability, the Hemi is backed by a Tilton four-plate clutch and G-Force four-speed gearbox. Wilwood six-pot (front) and four-pot (rear) brakes slow the nearly two-ton monster, while 15×10-inch Image Minilite wheels — the maximum allowed under HMC rules — wrapped in Hoosier cross-ply tyres, ensure the Cuda is plenty sure-footed.

Bic seam welded the body before fabricating the beautiful roll cage, which he designed to closely mimic that of the AAR cars — these were quite advanced, being developed from very early computer design. The fabrication work throughout is stunning, with clever thought going into every detail. To maintain the period look of the original car, Bic went for the ‘lots of rivets and alloy look of the ’70s’ to best fit the theme of the car, and give it added character.

An interesting quirk of this car — and its builder! — is the small amount of DNA manufactured into it, from a couple of other successful race cars Bic has been involved with. “I was quite heavily involved with Paul Stubber’s Camaro and Paul Sinclair’s Commodore (CMC cars),” explains Bic. “Over the years I’ve kept a bit of the roll cage tubing cut from each car as I’ve modded them. I’ve used some of each car’s tubing in the Cuda to build some ‘fast genes’ into it — call me superstitious, or a bit crazy!”

Once the fabrication work was complete, Bic had the body acid dipped to ensure all the muck was removed, then sent it to Lee at Tom Allen Panelbeating to add the last skim of filler, before it was sent to Joel Kamo at Airart Paint Worx for final paint.

“Joel gave us two colour options,” Bic said. “We hunted high and low for the exact Gurney colour but no joy, so Keith picked the final shade of blue and I think he nailed it.” Aside from the blue exterior, the Cuda’s engine bay, interior, boot, and underside have all been painted light grey. It’d be far easier just to paint everything navy blue, but that wouldn’t replicate the AAR cars. In period, painting these areas grey had a three-fold effect, and was common practice among Trans-Am teams: first, it helped lower cabin temperatures, which was important given that Trans-Am races ran for at least two hours and the cars had no power steering; second, it allowed oil leaks to be more visible; and, third, it allowed cracks in the bodywork to be detected more easily.

As in the original AAR cars, Keith’s Cuda also wears the factory rear spoiler, AAR fibreglass bonnet, and flat-pane front spoiler. The spoiler is of particular interest, as Bic tracked down the company that made the originals for the AAR team in 1970, essentially adding a few more ‘fast genes’.

The car was completed just in time for the Icebreaker event at Hampton Downs in early September 2014 — just 18 months after the plan to build the car was first hatched.

“I got it on the scales on the Wednesday before the meeting, set it up, and Keith came and picked it up on Thursday. Friday, we shook it down and we raced it all that weekend — done.”

The decals weren’t all applied for the Cuda’s first event, as time just ran out. But since then, the car has been finished off in exactly the same guise as Dan Gurney’s AAR machine.

Historic Muscle Cars have a motto: “The cars are the stars”. Keith Sinclair got this when he committed to this project, as did Bic, who, despite being naturally wired to build cars specifically for winning, was able to make the transition to building this car as cool as it could be. This mega-machine is a triumph on all levels, as, while Keith has fully enjoyed racing it, he has enjoyed owning it, showing it off, and polishing it just as much. The objective here, right from the outset, was ‘cool first, fast second’. This is a fast car! But even more so, it is very cool. The crowds that swarm around it at every event it has attended can testify to that. Job done!

1970 Plymouth Cuda

- Engine: 465ci Hemi, 426 block, Crower crank, Oliver rods, Diamond pistons, CNC ported iron heads, Stage V intake, twin BLP Holley carbs, Sonic surge tank, Aeromotive fuel pumps, Aeromotive regulator, Aeromotive filter, 120-litre fuel tank, MSD ignition, 2⅛-inch headers, twin three-inch exhaust, Spintech mufflers, C&R radiator, integrated oil cooler

- Driveline: G-Force GF4A four-speed gearbox, Tilton 7¼-inch four-plate clutch, Dana 60 diff, Truetrac centre, Endevour Engineering axles, floating hubs, Jerry Bickel driveshaft

- Suspension: Aftermarket torsion bars, multi-leaf rear, traction bars, adjustable Watt’s linkage, Penske two-way shocks

- Brakes: Tilton firewall-mounted pedal box, Wilwood six-piston front calipers, floating AP Racing rotors (front), Wilwood rear calipers, Wilwood rotors (rear)

- Wheels/Tyres: 15×10-inch Image Minilite wheels, 25.5×8.5×15 and 26.5×9.5×15 Hoosier tyres

- Exterior: AAR Cuda fibreglass bonnet, AAR boot-lid spoiler, Spies Hecker Patriot Blue paint

- Chassis: Seam welded

- Interior: Racetech seats, aftermarket steering wheel, pistol grip shifter, Auto Meter gauges, custom dash

- Performance: 700hp-plus