data-animation-override>

“Early Range Rover prices are rising — Donn Anderson explains why these unique vehicles are destined to become desirable classic cars”

Being first is not always the best outcome. Picture this: you are on Coromandel’s Hot Water Beach with a brand-new Range Rover stuck in the sand with an incoming tide, and there is no one around. It’s 1972 and the vehicle in trouble is one of the first Range Rovers to arrive in New Zealand … Yes, I almost became the first in our country to strand a Range Rover off road. It was a quiet Sunday at Coromandel, and I had nightmarish visions of phoning the distributor on Monday morning to give them the bad news that their Lincoln Green Range Rover GC8335 was languishing in the sand, half submerged in salt water.

There was only one thing for it. Tempt fate by heading down the soft sand, ever closer to a glowering ocean, then crank up sufficient speed and climb back up the beach to safety. It was a gamble that worked, and a highly relieved driver set forth back to Auckland in the late-afternoon sun. Our happy crew was now only concerned by the development of a noisy whine that sounded suspiciously like differential lock problems.

I deemed it prudent to make no comment about our beach dramas to the local distributor, New Zealand Leyland Motor Corporation, and they never told me what was awry with the transmission. Much later it was revealed an oil seal between the gearbox and transfer box had failed, as had an axle bearing.

Not a good start for a near-new vehicle, but clearly a baptism by fire. However, we had enjoyed a weekend of clambering over a Coromandel farm, fording streams, and cruising the open road in a machine destined to become a motoring icon. Decades later GC8335 was still giving service.

Crunching the numbers

This demonstrator was an early example off the Solihull line in a year when the production total of 5510 hardly scratched the surface of the car’s sales potential. It was launched on June 17, 1970, and a mere 2623 Range Rovers were built between then and the end of 1971, so unsurprisingly New Zealand was well down the pecking order for deliveries. By the time this first-generation model ended production in 1995, a total of 317,615 so-called Land Rover Range Rover Classics had been made, although some sources quote 325,490. The car’s best year was 1989, when 28,509 were built, and only 4000 rolled off the line in the last year of production, as the second-generation P38 generated more attention.

However, it says volumes for the Classic’s popularity that British Leyland continued production for almost two years after the P38 Range Rover had gone on sale.

Most vehicles came from Rover’s Solihull plant in the Midlands, but the Australians ran a completely knocked down (CKD) assembly programme for the first-generation Range Rover from 1979 until 1983, building the cars at Enfield in Sydney. Smaller CKD assembly was also undertaken in Costa Rica and Venezuela in 1974.

For more than four decades my dream collection of cars has always included at least one Range Rover. Each generation has its own charm, but none more so than the original two-door with its simplicity, function and, arguably, the best looks of any Range Rover. That the car would become a costly luxury fashion statement was never the intention, but a reflection of consumer demands.

Twenty-four years after the launch of the model Charles Spencer King, the talented engineer behind the machine, mused, “The Range Rover was never intended as a status symbol, but later incarnations of my design seem to be intended for this purpose.”

In the first decade of production, Range Rovers were relatively Spartan beasts, with plastic floor coverings (ideal for washing out after a day on the farm), heavyweight vinyl–covered seats, chunky door handles, Rostyle steel wheels, non-reclining front seats, limited equipment and clonky transfer boxes.

It took 11 years for British Leyland to be persuaded into offering a four-door version, and it was inevitable that the vehicle would head up market with automatic transmission and all measure of luxury equipment.

When the first examples arrived in New Zealand in 1971 they retailed for $6813, rising to $7434 the following year and $7683 in 1973. With high inflation, the Range Rover broke the $10k barrier in 1974, and by the mid ’80s the new list price topped $70,000. Until 1974 the value of used Range Rovers actually appreciated for their lucky owners.

The last of the Classics were sold in the mid ’90s with eye-watering retails of $114,990 for a manual, $119,990 in auto transmission mode, and $139,990 for a top-spec Vogue SE.

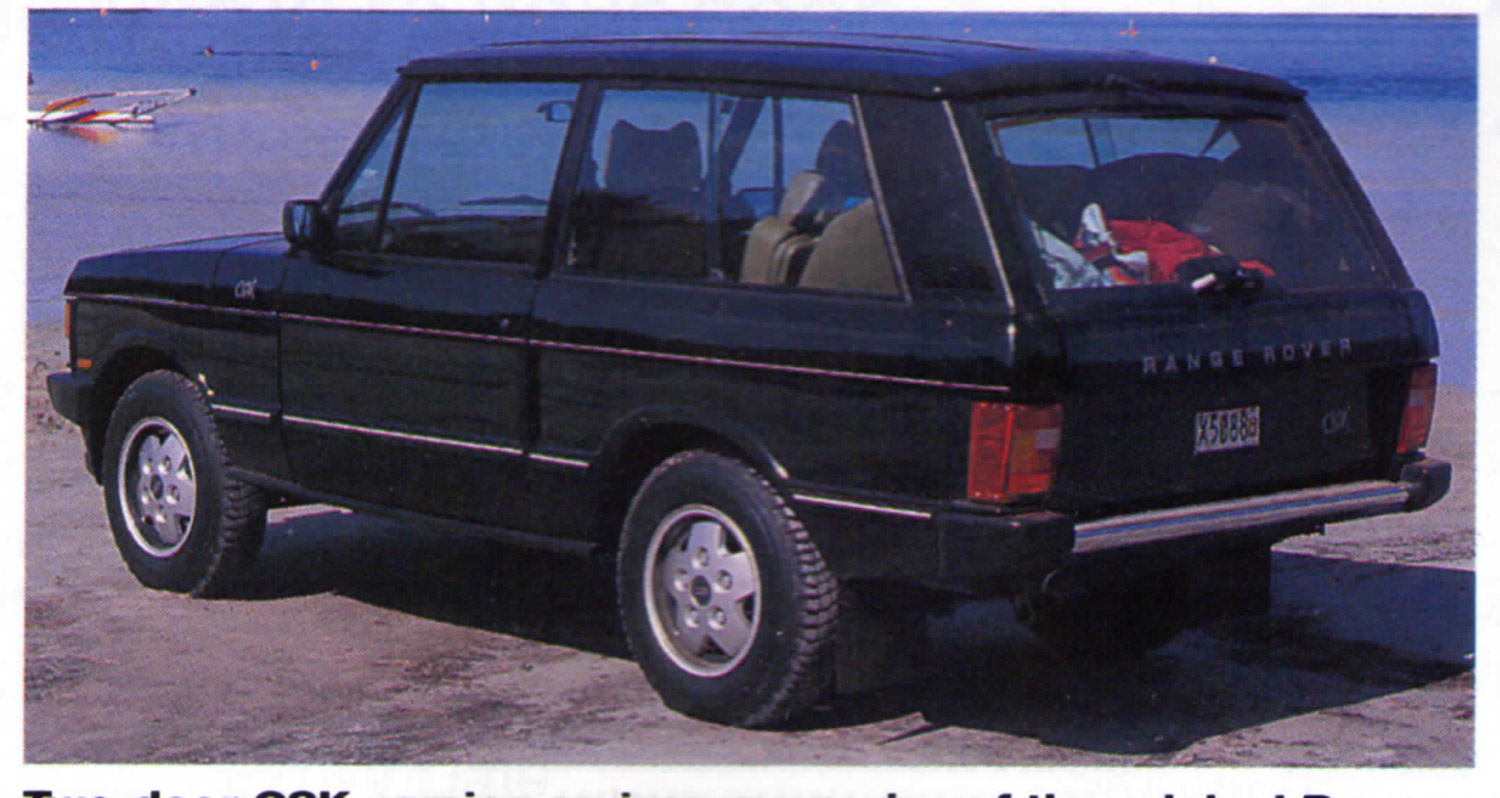

As a swan song for the two-door version and a tribute to Spen King, a limited-edition special, badged CSK, was launched late in 1990. Buyers snapped up the 200 units and most went to UK owners. Four went to South Africa, three to Australia, and New Zealand received 12, retailing at just under $100,000. Australia produced 400 of the CSK models, but they were based on the four-door Vogue.

The significance of the UK-built CSK, apart from its rarity value, is that it was the first Range Rover to embody suspension changes that made this unique SUV a much better highway proposition — changes later adapted to other Range Rover models.

Mechanical design

Sadly the three men responsible for the original Range Rover — Spen King (engineering), Gordon Bashford (engineering) and David Bache (styling) — have all passed away. Bache, who went on to style the Rover SD1 hatchback, was so impressed by King’s initial styling ideas and drawings that he made minimal changes to the eventual body shape. This is a rare car in that its body was shaped by the engineering team rather than a styling division.

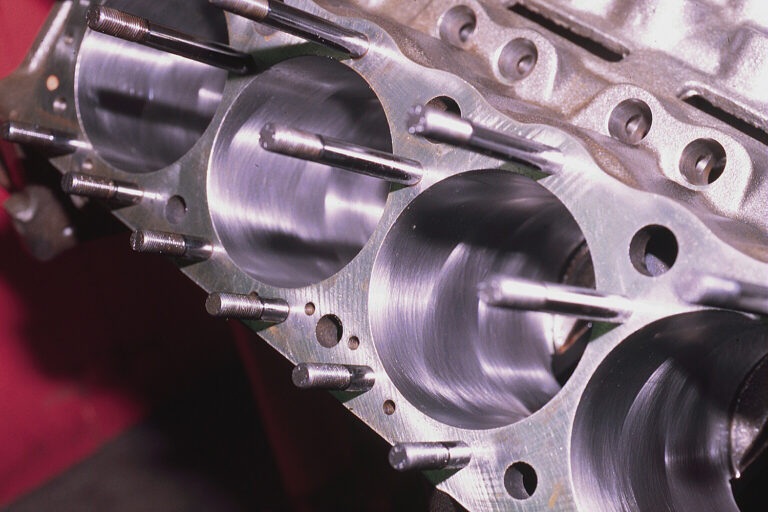

The venerable ex General Motors pushrod 3.5-litre alloy V8 fed by a pair of Zenith-Stromberg CD2 carburettors produced a modest 97kW (130bhp) and was upgraded with fuel injection in 1985, boosting power to 123kW (165bhp). A three-speed Chrysler Torqueflite automatic option was available from 1982, and the following year a five-speed manual gearbox replaced the four-speeder. From 1978 the car could be ordered with an optional Fairey overdrive unit. In 1987 a four-stage ZF auto replaced the three-speed component. At the tail end of 1989 the V8 was increased to 3.9 litres, while anti-lock brakes were introduced.

A long-wheelbase Vogue four-door arrived in 1992 with air suspension (which can be troublesome) and traction control, and in 1994 airbags became standard and the newer R380 gearbox was fitted. With an eye on the European market, the 2.5-litre Italian VM turbo-diesel four-cylinder engine became an option in 1986. This was replaced six years later by Land Rover’s own similar-capacity 200TDi, and then in 1994 by the 300TDi which was also 2.5 litres, and was smoother and quieter. Two versions of the VM — producing 84kW and then 89kW (112/119bhp) — gave modest performance, while the 200TDi produced no more power, and the 300TDi only improved to 91kW (122bhp). Little wonder these diesel Range Rovers were hardly inspiring performers.

Diesel Range Rovers were not officially imported into New Zealand until 1993, and the first manual-only examples cost $115,000, or around $5000 less than a petrol Vogue V8 auto.

Four cars in one

At launch in 1970 the first two-door Range Rover was launched as ‘four cars in one’ — a luxury car, a performance car, an estate and a cross-country car. With the four-speed gearbox and combined transfer gearbox giving eight forward and two reverse ratios, there was a gear for every situation. Permanent four-wheel drive had been achieved by incorporating a third differential, between the two driving axles, which could be locked at the flick of a switch to provide even better adhesion.

Driveline backlash is common on pre-1986 models, but the chain-drive transfer case with viscous-coupling differential lock that was introduced in 1989 is extremely reliable.

The self-levelling Boge Hydromat device was a strong selling point, along with four-wheel disc brakes and the sturdy beam axle and coil spring suspension that gave such a good ride. On early models you had to pay extra for the Adwest Varamatic power assistance for the Burman recirculating ball, worm and nut steering. The long-wheelbase four-door came late in Classic production and was heavier, had a worse turning circle and didn’t look as sharp as the other versions.

The separate box-section steel chassis had the strength of a Land Rover, and the double-skinned alloy outer skin was key to the lack of rusting. However, the body shell is fixed to the chassis with lots of bolts (likely to be rusty in old age), and there are weak spots around the front and rear crossmember, outriggers and coil-spring mounts.

Naturally, inner and outer sills are crucial to the shell’s strength, and the steel tailgates are prone to rust. You might joke that the toolkit is comprehensive because you will need it, but the contents are still impressive, and comprise pliers, screwdriver, tyre gauge, box spanner, tommy bar, six spanners, wheel brace, grease gun and jack.

Ignore the poor panel and bonnet fit since this is common to all first-generation models, and the gear whine on early examples largely disappeared in 1983 with the arrival of the five-speed gearbox. Never use the parking brake for emergencies as it feeds through the various joints, and causes the vehicle to slam to a halt if engaged on the move. Idler gear bearings in the transfer box are prone to wear, and while the V8 is extremely reliable, regular oil changes are advisable and help reduce premature camshaft wear.

Driving and travelling in a Range Rover is a special occasion, from the climb up into the cockpit and onto the aircraft-style front seats to admire excellent all-round visibility. Lack of power steering on some early models is a trial at slow speeds, and generous body roll may be a concern. Weighing in at around 1900kg, this may be a tall vehicle with heavy beam axles and ’60s technology, yet at launch it represented a new breed of dual-purpose car with good grip in all conditions.

Appreciating classic

Twenty years elapsed between my road test of an original Range Rover and the two-door CSK I drove in 1992, but I still enthused over what was the best luxury 4WD vehicle in the world. By the ’90s almost all new examples sold in New Zealand were automatics, and while the Japanese had improved both the off-road capability and specification levels of their SUVs, they were still unable to match the image and mana of the first-generation Range Rover.

This is a car that drives well in old age — a triumph of design engineering, marred only by sometimes iffy quality, poor-fitting trim and components with less than ideal reliability. You will need to persevere with heavy fuel consumption, but be reassured that your Classic Range Rover is a minimal depreciator, unlike everyday cars. In fact, the values of first-generation examples are clearly moving up.

Not everyone, of course, admires Range Rovers. One observer described them as “A shockingly unreliable, overpriced piece of British nonsense.” However, despite its well-known flaws, the original Range Rover has become an automotive icon with its timeless looks, practical split-tailgate arrangement and brilliant floating-roof design. Not to mention outstanding off-road manners and a certain charm no other manufacturer has been able to emulate.

Pick up the issue of issue of New Zealand Classic Car that this article was first published in: