data-animation-override>

“For many classic car enthusiasts, the catalyst for owning a car from a particular marque stems back to a first sighting of that model and the thought, ‘one day I’m going to own one of those’”

Phil O’Reilly, the owner of this glorious BMW M635CSi, clearly remembers ogling a blue example at Team McMillan in Remuera Road, Auckland, back in the mid ’80s — a time when red braces and big hair were in, and the world was our oyster. A time when little old New Zealand was destined to be a global financial powerhouse of the world, yes, Phil remembers those days well, he was a bright-eyed university student looking at it all in awe, and thinking he had missed the boat and wasn’t able to make his way as part of it.

Expensive luxury European cars were becoming commonplace on our roads during the ’80s, and one of the great status symbols then and now was a BMW. The E30 3 Series was current, and Phil remembers a mate who owned a red 325i coupé followed by a dark grey M325i. The design, the driving experience, the quality — but as far as Phil was concerned, the 6 Series stood at the pinnacle. He always stopped when he saw one (still does, as a matter of fact). The sleek lines, shark-like nose, cool boot spoiler and the drop-dead Hofmeister kink were all features that ticked the right boxes. Gentleman Jim Richards’ racing exploits in that stunning black JPS machine just added to the lustre of all things 6 Series.

Student dream

You have to admire Phil for his dogged perseverance, as it was many years before he finally attained his dream car — and he’s reasonably confident that his was the same one he saw at McMillan that day, as his Cirrus Blue M635CSi was sold new there. Phil doubts there are more than one or two NZ-new examples the same in the country, so that student dream may well have worked out more precisely than he could’ve imagined.

Chassis number 398 was one of the 20 or so M6s imported to New Zealand in the mid-to-late ’80s.

Like all the other New Zealand–new examples, it was an earlier, chrome-bumper model, and as well as that Cirrus Blue paint scheme it boasted black buffalo-hide leather — a unique combination amongst the 524 RHD cars built. Back in 1987, the BMW came with a heady price tag of $220,000. However, a quick sale was stymied by that year’s stock market crash, and the 635CSi didn’t find an owner until 1990.

Legend has it that the NZ M6s were actually destined for Australia, but were rejected due to Australian Design Rules. The cars were then redirected here at short notice, and distributed amongst BMW dealers for sale domestically. However, Phil reckons the Aussies have got their own back, as he knows of several New Zealand cars that are now in Australian hands.

When Phil first came into contact with chassis No. 398 some 15 years ago, he was actually going to do the same thing. He had a big corporate job in Sydney and thought ‘now’s the day’, and asked his brother to keep checking NZ Herald classifieds for an M635. Looking back, Phil concedes that it was a seriously stupid idea, even then, but he was a novice. Within a fortnight, Phil’s brother came back with not one, but two examples.

Phil had carried out some initial research on M6s and knew that the timing chain needed to be changed at around 160,000km. One of the examples had that work done after a complete engine rebuild when the old chain gave way, and the other had not had the work done yet, but had done 148,000km and was therefore was due for a replacement.

Phil wasted no time in flying back across the ditch to Auckland one long weekend to look at the latter car. It was best described as an honest example — not particularly clean or tidy, but with a full service history, and it was totally original. It was also within his price range. Phil was immediately smitten, and as they say, love does strange things. He bought the car and left it at McMillan to have the chain replaced. Five figures and several weeks later it emerged fit for another 100,000km.

Lessons learned

According to Phil there’s a couple of lessons to be learned from all of this — “Don’t do what I did. It cost me!”

Luckily he had the wherewithal to restore the car properly after purchase, but says it’s always best to do the right thing, join a local club and consult the experts. There are generally serious experts within classic car clubs who are only too willing to share their valuable knowledge, and if they don’t know the car you want to buy — walk away.

In this case, Phil shipped his dream car to Sydney and, as is the way with the truly naïve, thought it would be a simple task to make it perfect. In some senses it was. For example, most of the M6s he’d seen needed serious detailing from top to toe for starters — not a problem for Phil, as he enjoyed spending literally hundreds of hours on the car restoring leather, cleaning and degreasing everything and polishing — all of which, he admits, made a real difference.

Phil’s not one to modify his cars, he certainly respects what the M engineers were trying to achieve, and wanted to recreate essentially the same car which came from the factory. He was helped by the fact that No. 398 was absolutely unmodified, just a bit tired, and set out with a vengeance to return it to factory fresh condition.

This is where he learned his second lesson — if you want to restore a classic performance Beemer (of any variety), get to know some fanatics at your local dealer parts department. Phil found a friend at BMW in Sydney who was more fussy about locating the correct parts than Phil — he helped out by sourcing exactly the right windscreen-washer bottle (the 635CSi also has headlamp washers), and the correct oil cloth for the toolkit. Find one of those guys to help and, to a large extent, most of your problems will go away — just bring a very hefty cheque book.

Phil once heard a joke about BMW parts prices — if it’s a BMW part it’s expensive, if it’s a 6 Series part double the price, and if it’s an M6 part double it again. He can attest to this, and admits that some of the M6’s unique parts are eye-wateringly expensive.

This is where Phil learned lesson number three — don’t buy the best car you can afford, just buy the best car! If you can’t afford it, keep saving. You’ll save yourself a fortune in the long run. Phil modestly admits that his car is now one of the best in the country, maybe the world, but it cost him a lot of money along the way — if he’d bought better in the first place that needn’t have been the case.

For example, some of the searches for parts became a real mission. The tyres are a famous example. The original M6s came with a 415mm rim. Remember, this was in the days when metric was going to take over the world, and Michelin was going to be at the forefront of it all. So, in what must have been a decision made over a couple of serious steins of ale, the Germans put metric tyres on the M6. Other well-known mainstream models that sported metric rubber include the largely unloved Ferrari Mondiale.

To call these tyres rare would be something of an understatement, and most owners have since given up and gone to imperial wheels and rubber. But for Phil, originality rules, and he searched the world for 415mm Michelin TRX GT tyres. He finally found them on sale for a bank-busting price in the USA, bit the bullet and bought eight of them, just in case Michelin ever stopped making them.

One of Phil’s favourite searches, however, involved a stereo-cassette head unit. The unit in the car was cheap and nasty rubbish and, initially, Phil resigned himself to the fact that it would be difficult, if not impossible, to find a genuine replacement. For once, BMW was unable to help, so he spent two years searching eBay Germany for the right unit — and it now sits in his car. Another fun search was for the original, and now exceedingly rare, red-handled (not left-handed) screwdrivers for the tool kit in the boot. Phil found them in the USA after years of searching and no, you certainly don’t want to know the price. Even Phil’s car-fanatic brother rolled his eyes at that one.

And yet another lesson Phil feels he should pass on — find a mechanic who loves your car as much as you do, and let them get on with it.

Restored in New Zealand

Phil relocated to Wellington in 2005, and despite completing a great deal of work on the car over the years, he decided it wasn’t enough. He wanted only the very best for his BMW, and says you can only go so far with this type of vehicle if you’re just handling ongoing minor work. At the end of the day, if you want a world-class example, a full restoration is called for. That happened over nine months or so during 2014, under the expert guidance of The Surgery in Tawa, Wellington.

Phil says he had confidence in going ahead with it because he found three great partners — Mike Bauke and his team at The Surgery, who coordinated the restoration effort, Vijay and the team at Page European, who lovingly maintained the car while it lived in Wellington, and the Jeff Grey BMW team — also in Wellington, and absolutely committed to sourcing the right OEM parts to complement the restoration effort, no small task given the age and rarity of these cars. Phil’s wife provided much-needed support too — a vital aspect, of course!

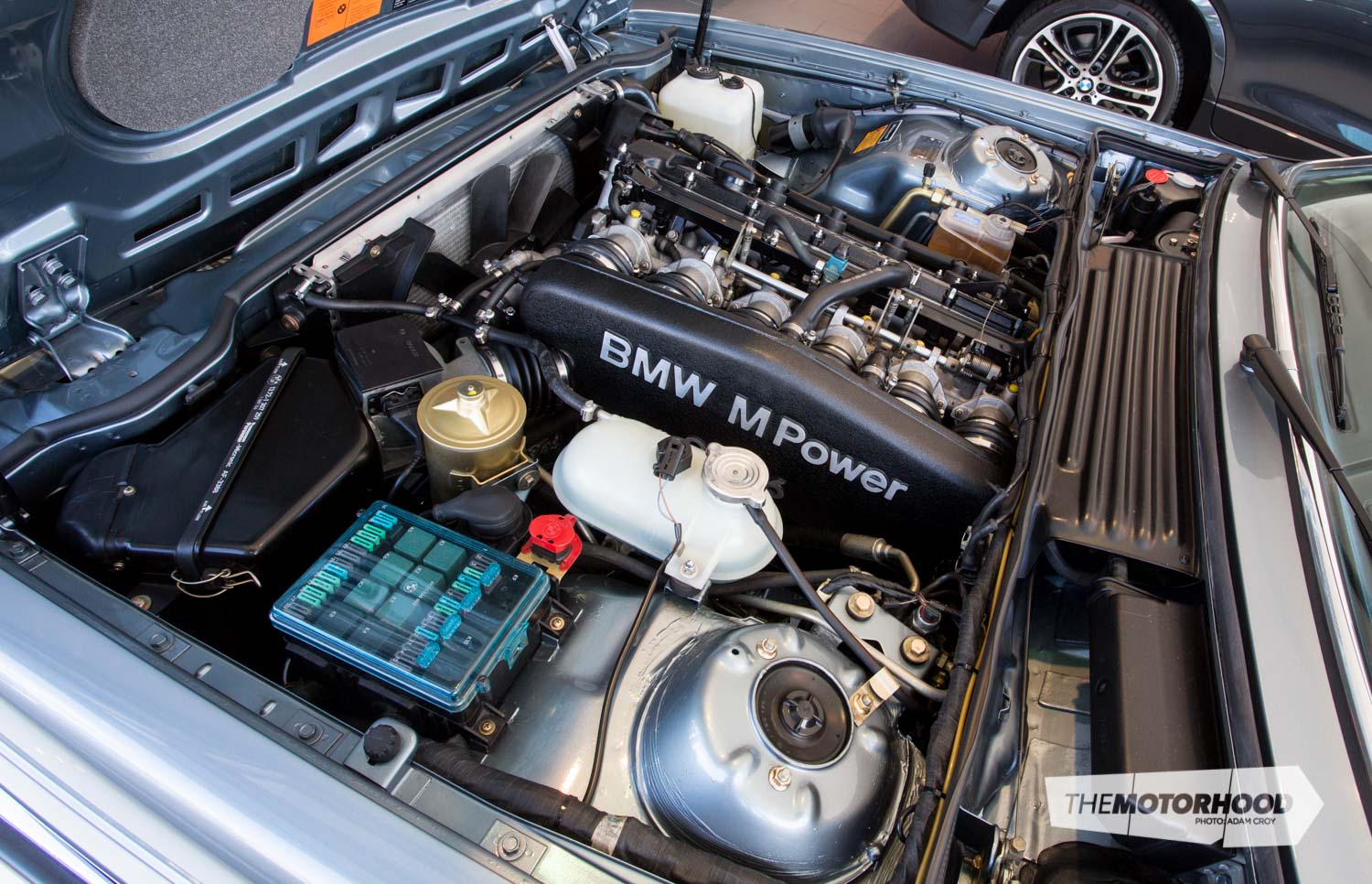

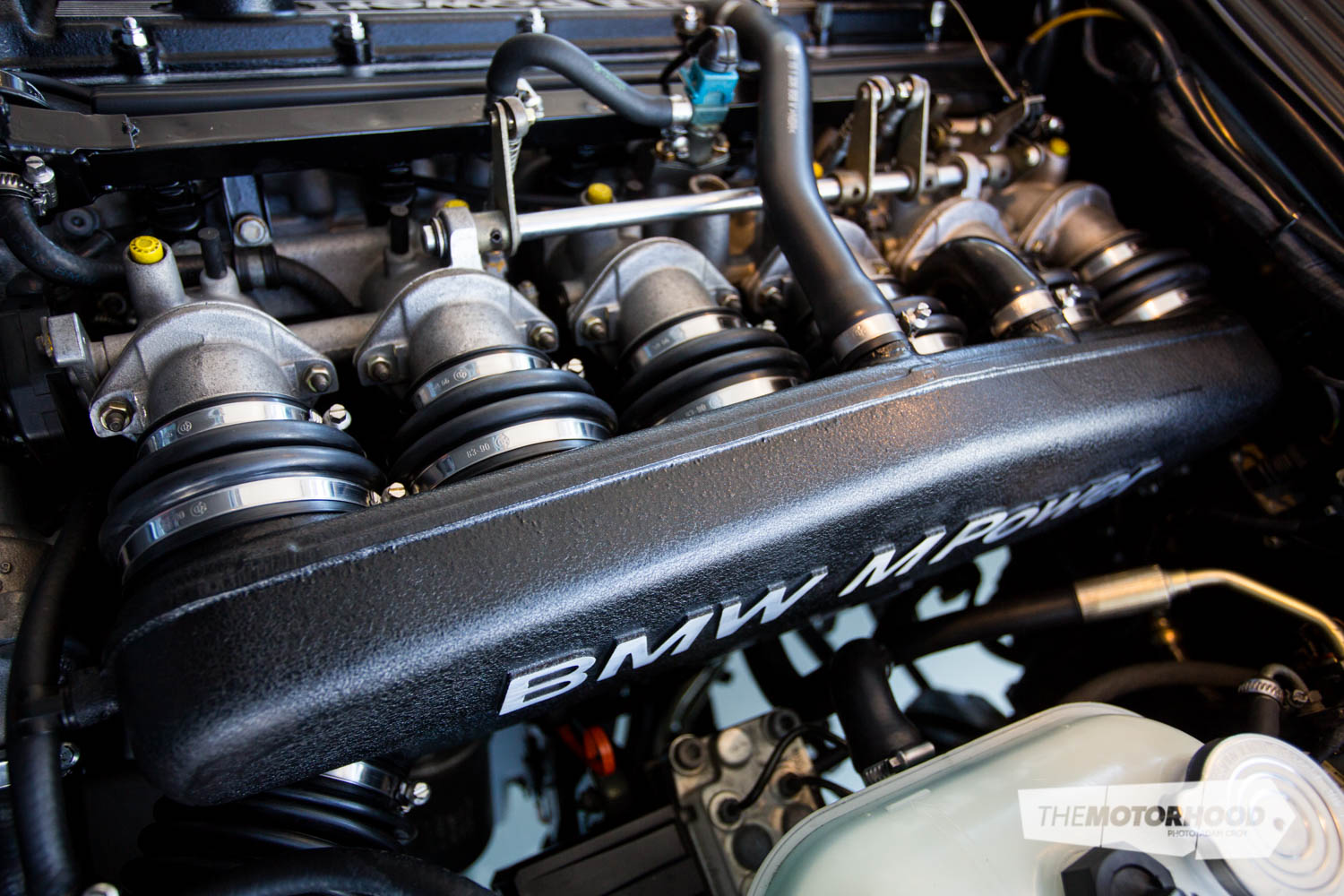

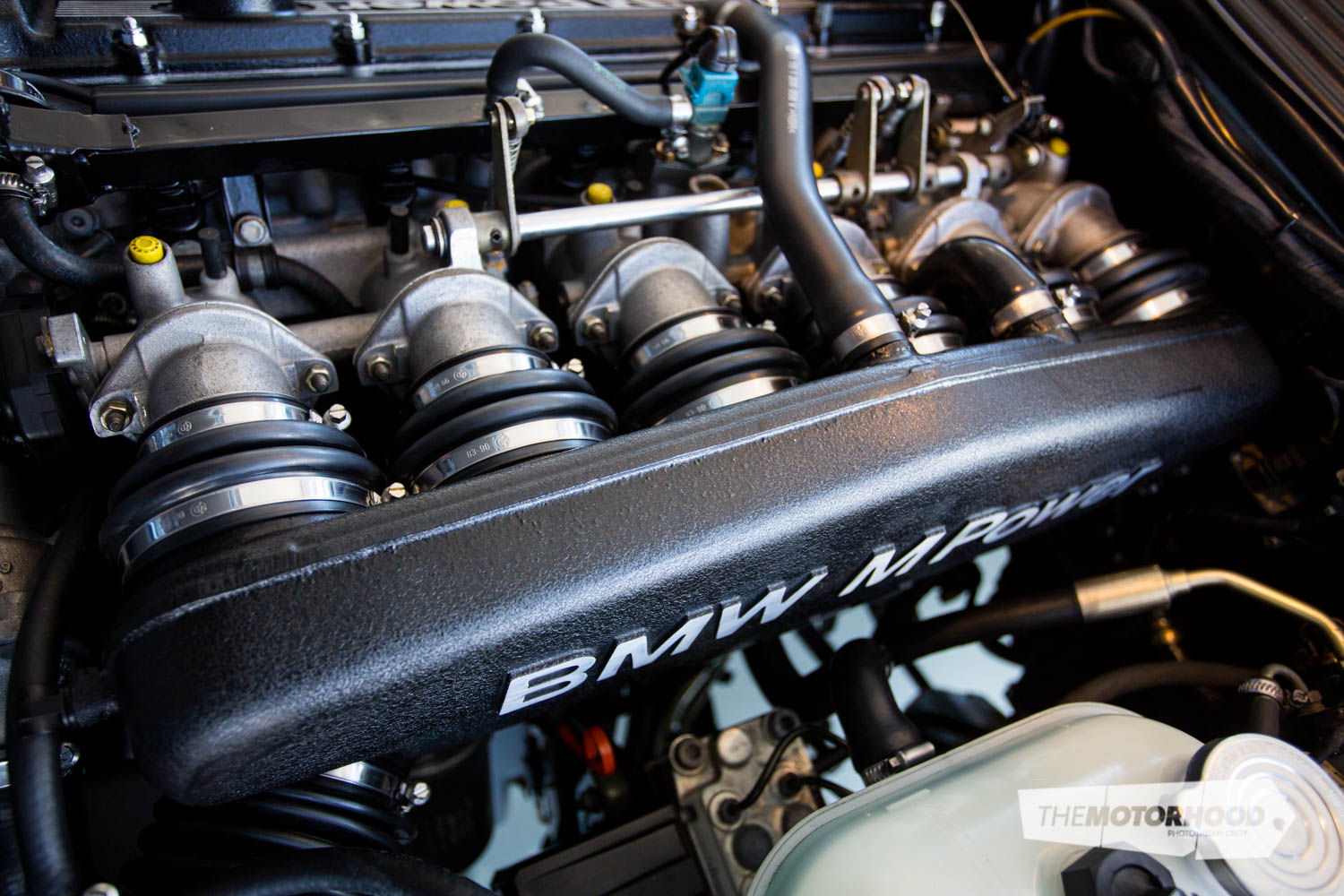

The full restoration started with the removal of the engine and transmission before the car was completely disassembled to a bare shell. The underside was stripped back and resealed with factory-correct textured stone-guard film, whilst the front and rear suspension components were totally refurbished and repainted in the correct, factory satin black. The fuel lines and brake lines were replaced along with shock absorbers and brake rotors, and the brake calipers were reconditioned.

A new cross member was fitted, as poor jacking techniques over the years had caused a few unsightly dents. The body, including the engine bay, was treated to a fresh coat of Cirrus Blue paint, and the engine also received a thorough clean and repaint. Engine work was carried out by Page European in Wellington. The vital timing chain and top-end overhaul was done some time ago and no internal refurbishment was required, although all valves, hoses and peripherals were replaced if parts were available. Page European reinstalled the engine and transmission.

The original wiring loom was still in good shape and just required re-taping, with the factory original tape, of course.The perfectly original interior was left relatively untouched. The headlining was replaced, and a general tidy-up including cleaning and re-moisturizing the leather and dry cleaning the original carpets brought the interior back to its former glory.

Essentially, if Phil could replace any part with a new OEM part, then that’s what happened. This meant new trim, headlights, screens, bumpers, mufflers, shocks, brakes, and underside plumbing, just to name a few items. What wasn’t replaced was completely refurbished, cleaned and painted.

The restoration team was key, according to Phil. Mike and his team continually challenged him to do the right thing by the car. They talked together often to discuss the best way forward, including jointly researching detail issues from all around the world. That led to a restoration which was completed to a very high standard, and at reasonable cost. Everyone Phil dealt with was really proud to be part of the project, really enjoying the little moments of the journey together — finding a rare part, searching web forums for insights, talking to overseas experts, and researching why different things had been done to the car when it was at the factory.

That team effort was marked by an official ‘launch function’ at Jeff Grey BMW in Wellington late in 2014 with 70 friends attending, including (in typical Kiwi style) everyone from the mechanics and technicians who had worked on the car, to the German Ambassador. All three generations of the M6 were on display.

So, after having spent many years getting the car to concours condition, would he do it again? “Absolutely!” says Phil, who reckons the project was one of the most fun things he’s ever done.

His wife says that he sometimes goes to where the BMW is parked just to look at it — but it’s as much about feeling good about what’s been achieved as it is about drinking in the M6’s well-balanced lines, not to mention recalling many spirited drives on the open road. Phil reckons the sound of that glorious Roche-designed six cylinder is still spine-tingling — and he enjoys it all the better for knowing all the hard slog he and his friends went through to get the car to where it is today.

1986 BMW M635CSi

- Engine: Straight-six

- Capacity: 3453cc

- Bore/stroke: 92 x 86mm

- Valves: Four per cylinder

- Comp Ratio: 10.5:1

- Max power: 210kW @ 6500rpm

- Max torque: 340Nm @ 4000rpm

- Fuel system: Electronic fuel-injection

- Transmission: Five-speed manual

- Suspension F/R: Double-pivot McPherson struts/Semi-trailing arm

- Steering: Recirculating ball

- Brakes F/R: Ventilated disc/disc

- Overall Length: 4755mm

- Width: 1725mm

- Height: 1365mm

- Wheelbase: 2625mm

- Front Track: 1430mm

- Rear Track: 1460mm

- Kerb weight: 1460kg

- Max speed: 255 km/h

- 0–100 km/h: 6.4 seconds

- Standing ¼ mile: 14 seconds

Buy a copy of the magazine this article first appeared in below: