data-animation-override>

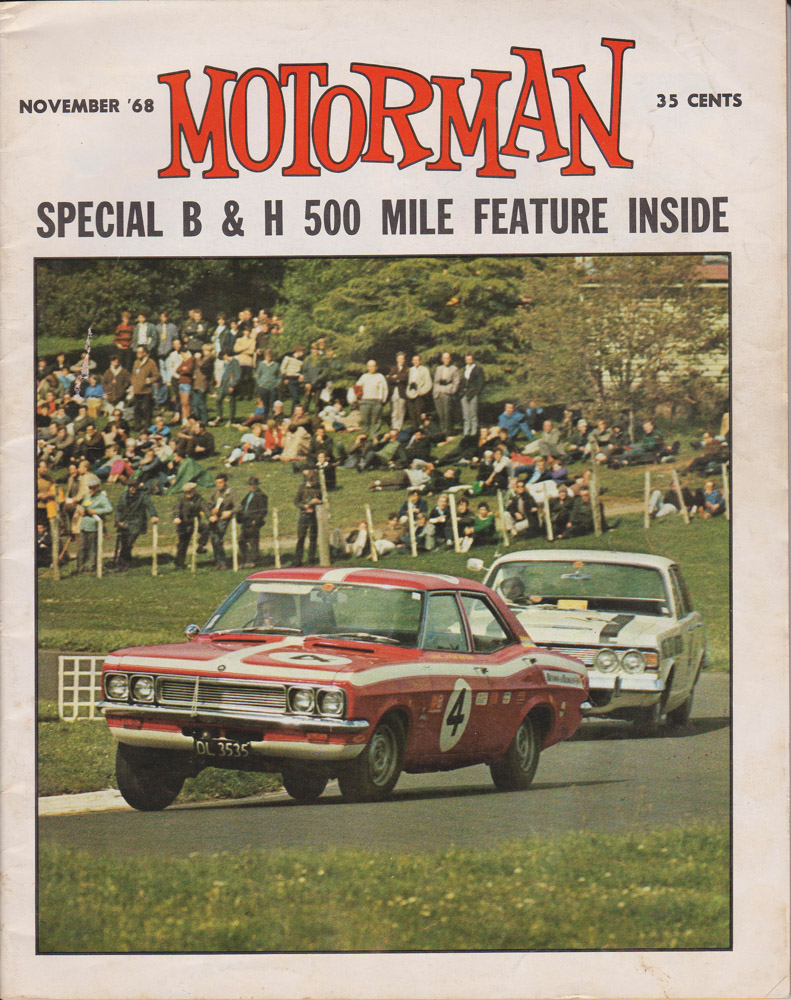

“The Benson and Hedges race series provided the battleground for market share of locally assembled cars in New Zealand in the decade to 1978”

Leafing through magazines up in my ‘man cave’ the other day, I came across a couple of articles in Australian motoring publications that set me to thinking. The general take was, ‘wake up! The end of an auto dynasty is nigh, and now’s the time to save whatever examples are left of the previous era’s home-grown cars’.

Two pieces seized my imagination — in particular, a saga relating to an Isuzu Bellett that was, literally, gifted to a collector. It turned out that this Isuzu possessed real competition provenance, having raced in the 1966 Gallagher 500, the forerunner to the Hardie-Ferodo 500/1000. Nowadays any survivors that raced at Mt Panorama during those early years are regarded with the greatest reverence. The Bellett referred to, an Australian-assembled rarity, was basically an unmolested non-runner that had previously been stuck in a shed, its heritage unknown until a collector unearthed it.

This story fired my imagination, and got me thinking about the possibility that some genuine New Zealand–assembled production racing survivors might still be out there, possibly holed up in a barn somewhere or lying forgotten at the back of a shed.

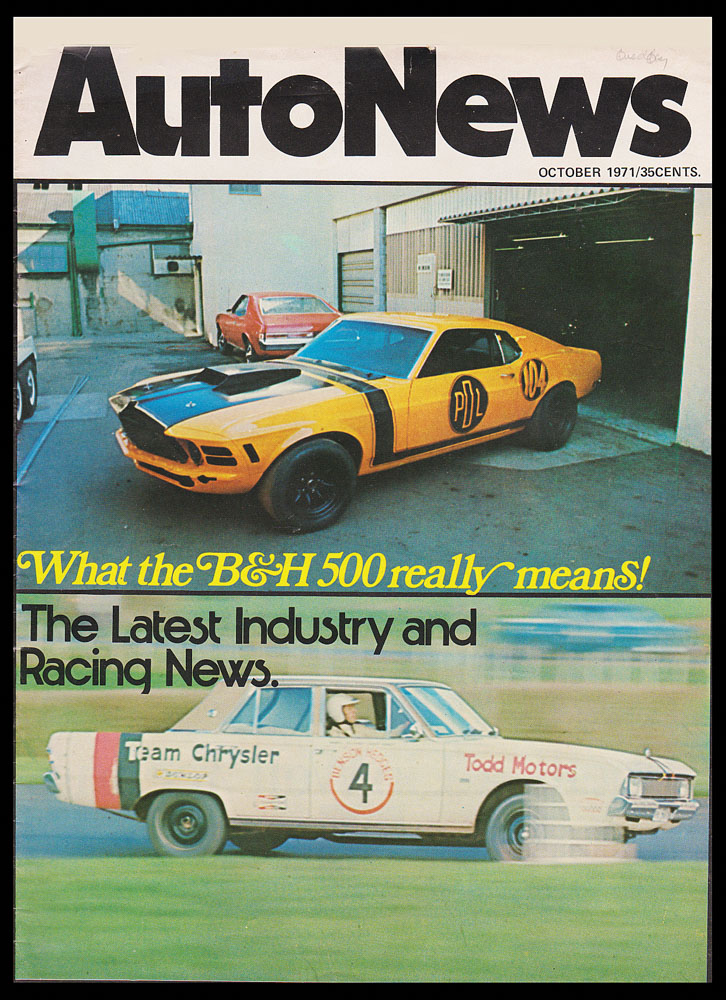

I’m talking about cars of the ’60s Wills Six Hours and the Benson and Hedges 500/1000 races. That was a time when the magic of these races was the battle for supremacy between locally assembled production cars before it all went crazy post 1978 with exotic, limited-manufacturing runs of imported high-performance factory specials. Not that certain local manufacturers didn’t have this idea as well — witness the 1972 Fiat 125T and the later Datsun 1200SSS — but neither of those home-grown cars could live with the Chrysler Charger. More about that later.

Local assembly

The era of local automobile assembly in New Zealand stretched from 1921 to 1998 — everything after that being imported in fully built-up form. The removal of sales tax on new vehicles in 1998 effectively sounded the death knell for our auto-building industry. Today, I’m picking that, in Australia, pristine examples of surviving locally built cars will gain in value with the passing of time. These cars are truly icons redolent of our motoring past, and a time when there was a thriving, buoyant local car-assembly industry in New Zealand.

And it’s not just the Jaguars, Rover V8s, and Chrysler Chargers, amongst many others, that hit the spotlight — like that earlier mentioned, humble but cute Isuzu Bellett, the mass production of the early Datsuns, Toyotas, and Mazdas, plus their English counterparts, reawakened my interest in this era of local assembly.

While delving into some local production records, I experienced a small rush of excitement when I realized the twin-cam Corolla I own was one of the very last to go down the line at Toyota’s Thames plant in late 1998. I can hear the sceptics slating anything oriental, let alone New Zealand–assembled, as unworthy of being considered a classic — heresy!

However, I haven’t lost my grip on reality, and remain unrepentant as I state loud and clear that the vehicles built in New Zealand during the period in question represent a truly significant aspect of the history and growth of the motor-vehicle industry in this country.

With assembly of CKD (completely knocked down) vehicles came the establishment of subsidiary industries supplying components to the major car companies. Over time the automobile industry and roading infrastructure that we now take for granted evolved as a result of increased car ownership — in itself a direct result of a local motor-vehicle assembly that meant vehicles were cheaper and more accessible.

There were those who viewed early Toyotas and Datsuns as cheaply made, of poor quality and unreliable, but they quickly established themselves as totally the opposite — even if wider public perception took a while to change. With standard equipment that cast their English opposition into the shadows, their design and construction were excellent, but the real master stroke for these Japanese cars was their bulletproof engines — they thrived on revs, perfect for racing!

The institution of the Benson and Hedges 500 endurance race — developed for standard production, locally assembled saloons — came at what proved to be perfect timing for the early beginnings of what became the Japanese ‘invasion’.

While I have a real passion for this first wave of Japanese autos from the late ’60s and ’70s, I will concede that until the first oil shocks of the mid ’70s, the local assembly of British and Australian products provided the mainstay of our national car fleet.

With Ford assembly based in Petone (Wellington) from the ’30s, later entrants included General Motors, Vauxhall, and Holden in Otahuhu / Mount Wellington (Auckland). Todd Motors was assembling Chryslers and other makes (Mitsubishi) at Todd Park in Porirua (Wellington), and in Nelson, Triumph, Rover, and Jaguar cars were being built. These were among the larger players, though Campbell Motors’ assembly of Toyota and Datsun vehicles figured more prominently into the mid ’70s and beyond.

GM Holden and Vauxhall vied with their equivalent Australian and English Ford counterparts for supremacy of the local market throughout the ’60s and much of the ’70s. However, by the late ’60s there existed a wide array of locally assembled brands — including European marques such as Fiat and Renault Simca — all of them competing for market share. And what better showcase than a long-distance endurance production-car race to advertise the quality of your wares?

New Zealand’s toughest motor race

Cigarette advertising was the name of the game back in the ’60s, and Wills Tobacco Company certainly saw a good thing when it fronted a sponsorship deal to back the long-distance endurance race held at Pukekohe circuit from 1964 to the mid ’80s.

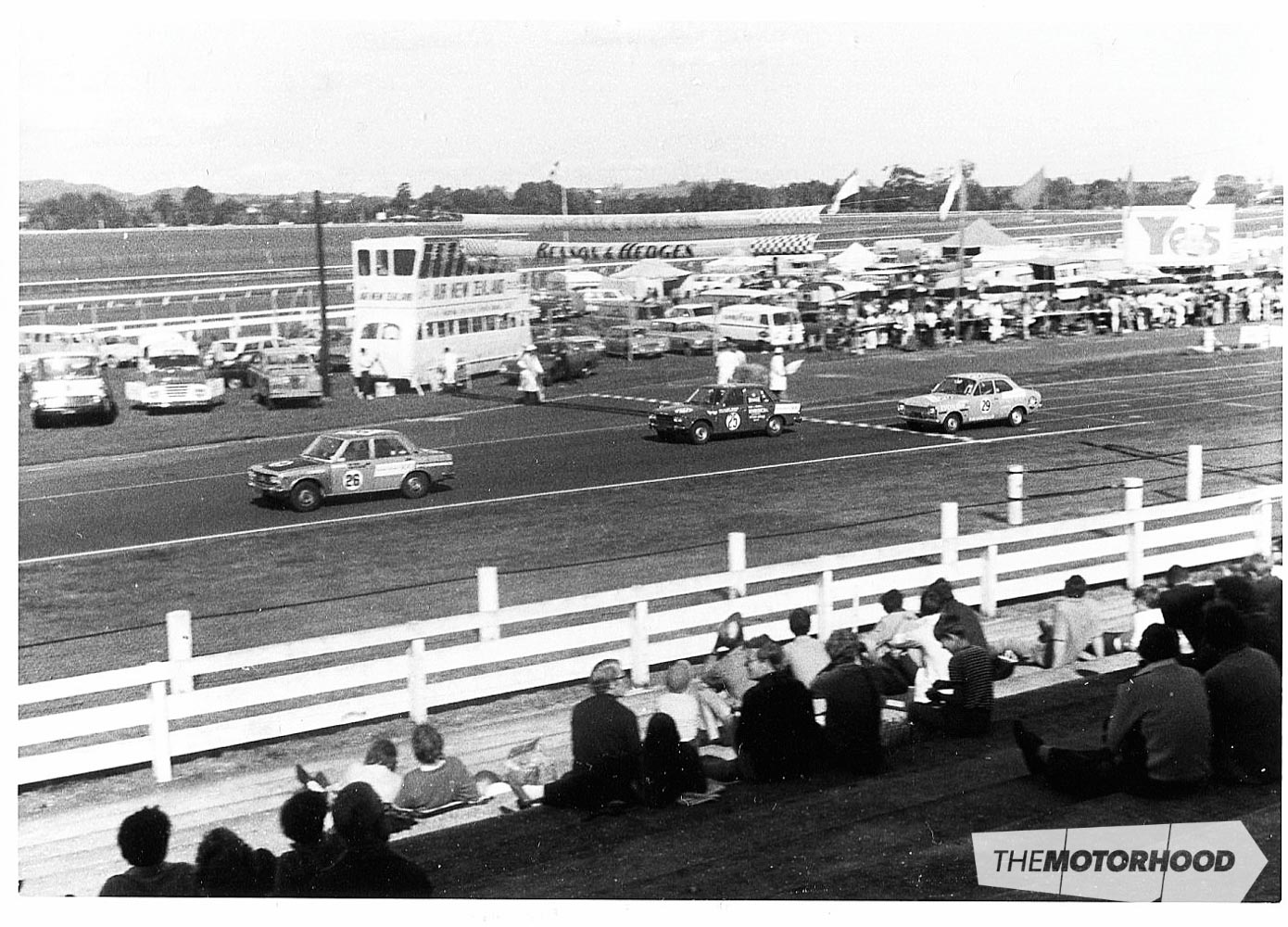

And the subsequent Benson and Hedges 500-mile race for locally assembled cars really ignited the public’s interest in how their favoured brands could front up to the opposition. More than any other period in local motor racing, the punter in the street could relate directly to machinery that was racing on the track as being close to what could be purchased off the showroom floor.

The hard-core motor-racing addict aside, your average bloke in the street with an interest in cars, rather than racing itself, enjoyed this event. If they didn’t always turn up in droves at Pukekohe, though crowds were inevitably good, they certainly followed the race — barracking with their mates for their preferred make. Brand loyalty had a lot to do with this style of racing, even then.

And in the jungle of the schoolyard during the end of the ’60s and early ’70s, when I wasn’t setting the academic world alight, these Benson and Hedges races directly fed into my greater hunger for all things motor racing, and I wasn’t alone in this — many vigorous ‘discussions’ often took place around Benson and Hedges time. We all had our allegiances — largely based on what your dad drove. My brother and I were in the GM camp — the old man’s sequence of Holdens and a Vauxhall Cresta during this time casting a powerful spell over us for their latest machines.

Back then, the FD Vauxhall Victor had serious street cred, and the hot rod Victors were the ‘top guns’ of the first two Benson and Hedges 500 races, and my ultimate favourite. They looked quite sexy, yet were very compact with their swoopy waistline, and with an ideal wheelbase they handled well, despite the weight of their cast-iron 3.3-litre six-cylinder donk. Some time later, the Vauxhall’s qualities wouldn’t escape the ace race-car builder, Jimmy Stone, who chose the FD Victor as the basis for Jack Nazer’s legendary Chev-powered Miss Victorious.

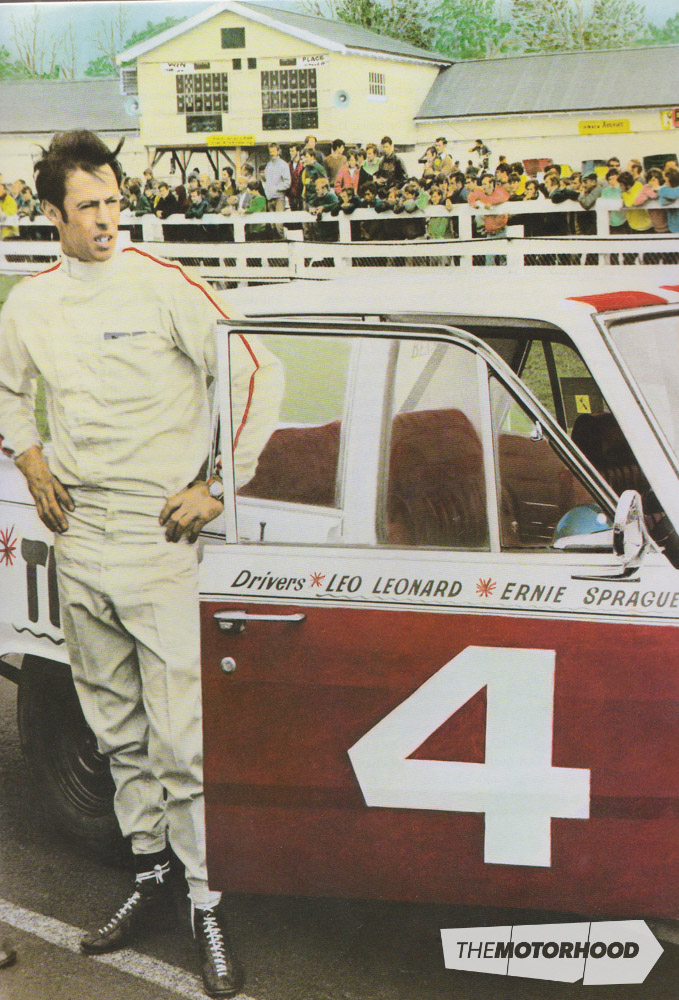

By the 1969 Benson and Hedges race, the Victor had real competition as the 5.2-litre Chrysler Valiant Regal V8 appeared and was faster — but Leo Leonard and Ernie Sprague tactically outfoxed them to win a great race, though more about that later. The Valiant was an impressive runner, and would have its day in the sun very soon.

My father’s ’66 Vauxhall Cresta was powered by the same 3.3-litre power plant as the Benson and Hedges–winning Victors, just in a slightly heavier body. Association was everything though, and it felt as though we were hardwired into the rarefied glamour of the racing elite. Delusions are free, of course, but the fact that an identical Cresta scored a third outright in 1966 with Frank Bryan and Don David at the wheel hadn’t escaped my notice.

I guess you’re getting the picture — the race was a big deal, because it really did capture our imaginations. The ultimate reason being, as previously mentioned, that these were standard production cars being flogged to within an inch of their life over seven to eight hours, with all the drama that brings. It’s not hard to imagine the challenges of racing for hours on a slippery, oily track surface with fading brakes, tired gearboxes, faltering clutches and skinny rubber — all on New Zealand’s most-demanding race circuit.

Another big drawcard was that most of the top local circuit racers from all other motor sport categories turned out for our ‘great race’. It certainly was a big day when the 500-mile battle took place — always, it seemed, in adverse weather conditions — each September.

Boy’s own heroics

Pukekohe was our home track, the longest permanent racing circuit in the country — and the fastest. The Benson and Hedges always used what was termed as the long circuit, this included the section known as ‘The Loop’ that created an extremely tight left-hand corner off pit straight — ‘The Elbow’ — and was the downfall of many drivers, especially for those of the demon late-braking variety. There was always the potential for carnage here, and the adjacent spectator area was invariably packed.

The annual ‘pilgrimage’ to Pukekohe for the Benson and Hedges 500 was not for the faint-hearted during these years. As young lads without wheels, the trip involved a marathon bus expedition from Auckland’s North Shore. Duffel bags were crammed with provisions, such as egg sandwiches, although they quickly lost their appeal when we caught sight of the hot-chip stand.

As we settled in to watch the racing, it seemed that the heavens would open up and dump their contents on us — usually several times — and the oilskin raincoats that were the style of the day seemed to sweat more moisture than they repelled.

September in Auckland — the weather is always notoriously unreliable, and Pukekohe on Benson and Hedges days seemed to have an unshakeable deal with the rain gods! Of course, this wasn’t all bad — as they say, once you’re wet, you can’t get wetter, and the action on the track also got better as it got wetter (in our eyes at least). The mix of rain, oil, and grease provided a slippery surface that, along with fading brakes and worn tyres, meant something had to give.

We generally stationed ourselves at the hairpin bend at the end of the main straight (Lion Motors Hairpin), hanging around like vultures waiting for victims and, in due course, we were always rewarded with some excellent spin-outs, ‘grass cutting’, and an occasional major lose. The unlucky combatant usually disappeared backwards out of sight at high velocity into the old tyres piled up a short distance beyond the run-off area. This, of course, was the cause of much celebration and revelry by the heartless hairpin spectator mob.

We were hell-bent on scoring the ultimate viewing spot closest to the action, and this inevitably meant locking horns with the dreaded ‘white coats’ — the over officious, seemingly power-hungry car-club stalwarts whose only mission in life appeared to be to thwart our pleasure. It never occurred to us that they might be trying to keep us safe and, naturally, when they were out of sight, or had their backs turned, we would surreptitiously advance into non-spectator zones, to grab a few photos.

For years our main nemesis was a ginger-headed character who was always stationed within the esses and hairpin area — over the years, we engaged in a strange battle of cat and mice with this chap. On arrival at ‘his’ section of the track we noted his presence with some perverse pleasure, and the statement, “Old Ginger’s back — let game commence”.

Staying hydrated throughout a long arduous day of watching cars hurtle by wasn’t a fashion statement in 1970, rather involving the inevitable bottle of pop or the contents of a thermos. Whatever, imbibing liquids always meant the grim reality of a visit to the infamous Pukekohe latrines on the furthest outposts of the circuit had to be endured. These sacking-doored holes in the ground were a real test of will, and the smell of those diabolical ‘facilities’ could scar you for life! I often thought a T-shirt with the logo ‘I braved Puke’s long drops and survived!’ would have been a sure seller!

Back to the racing, and I have to say that at the time it was the shorter 100-mile race (in the morning) for high-performance imported factory limited-production cars that was the ace in the deck which lured us young teens to Pukekohe for the B&H. While I certainly enjoyed the B&H, back then I was pretty much seduced by the more potent hardware. Don’t get me wrong, I was intrigued with the 500 race, but it’s only been in later years that my fascination for it has really mushroomed, along with my interest in NZ-assembled autos.

Legendary Benson and Hedges drives

Striding like a titan over the tough contest of the Benson and Hedges series was Leo Leonard, who I make no apologies about rating as the most accomplished long-distance racer this country has seen. New Zealand’s equivalent of Peter Brock, in other words. High praise, especially when you consider other local stars such as Jim Richards and Rod Coppins, amongst many others.

However, Leo and Ernie Sprague (later Ernie’s son, Gary, took over from his father) were the ultimate pairing, along the lines of Peter Brock and Harry Firth. They were tactical masters who allied the advantage of superb car preparation with skilful driving in conserving their machinery while driving quickly — not to mention their ability to read a race more astutely than their opposition.

Both Leonard and Sprague operated automotive businesses in the South Island seaside town of Timaru. A real veteran, Sprague had been racing and preparing competition machinery as diverse as an ex Maserati Formula One car and a ’32 Ford V8 roadster since the early ’50s. Leonard had formed a business partnership with well-known sports-car racer, Brent Hawes, in 1965. Tragically, Hawes lost his life at Ruapuna driving his Begg-Chevrolet sports racer in May 1969. Only eight months before, Leonard and Hawes had shared the winning Vauxhall Victor 3.3-litre at the inaugural Benson and Hedges 500.

This was the beginning of a four-race-winning blitz for Leo, who stamped his name on this event in commanding style. Masterminding the team and co-driving for Leonard for two of these victories was the wily old fox, Ernie Sprague. None of these wins were easy, particularly the 1969 race when they were outgunned by the Valiant V8s. That year, they played a waiting game early on before exerting pressure on the Todd Chrysler entries during the latter stages of the race. Failing brakes on the Valiants opened the way for a second Vauxhall Victor win for the Timaru-based team.

It is interesting to note that in the 1968 race, both the front-running Victors (clutch and gearbox dramas) and the Ford Zephyrs (diff and overheating issues) suffered rampant reliability issues. With the exception of the Timaru contingent that is, with Leo and Ernie — on this occasion driving in separate cars — coming first and second. Leo and Brent in the Victor headed home Ernie and Gary Sprague’s 3.0-litre Ford Zodiac V6. For a time it looked as though there might have been a major upset when Dennis Marwood and Brian Innes surged into contention from way down the grid in their beautifully driven Datsun 1600.

Upsetting the old order, the Datsun surprised with its amazing pace and bulletproof reliability. It looked as though there might be a huge upset, with the British heavy artillery seemingly dropping like flies. Marwood and Innes eventually finished fourth outright and, as Donn Anderson commented in his race report, unlike the majority of contenders the Datsun’s bonnet wasn’t raised throughout the race, and it went the distance on one set of brakes and tyres. It was a big wake-up call for the traditional market leaders — although at the time, none of them truly took this on board.

The only Victor to have a faultless run was the Leonard/Hawes car, which with a skilful race strategy came through to win in the final laps, overtaking the late race-leader Graham Harvey when his Victor suffered complete brake failure and holding out Ernie’s Zodiac, which was closing after changing brake pads in the latter stages. It was another great victory for Leonard.

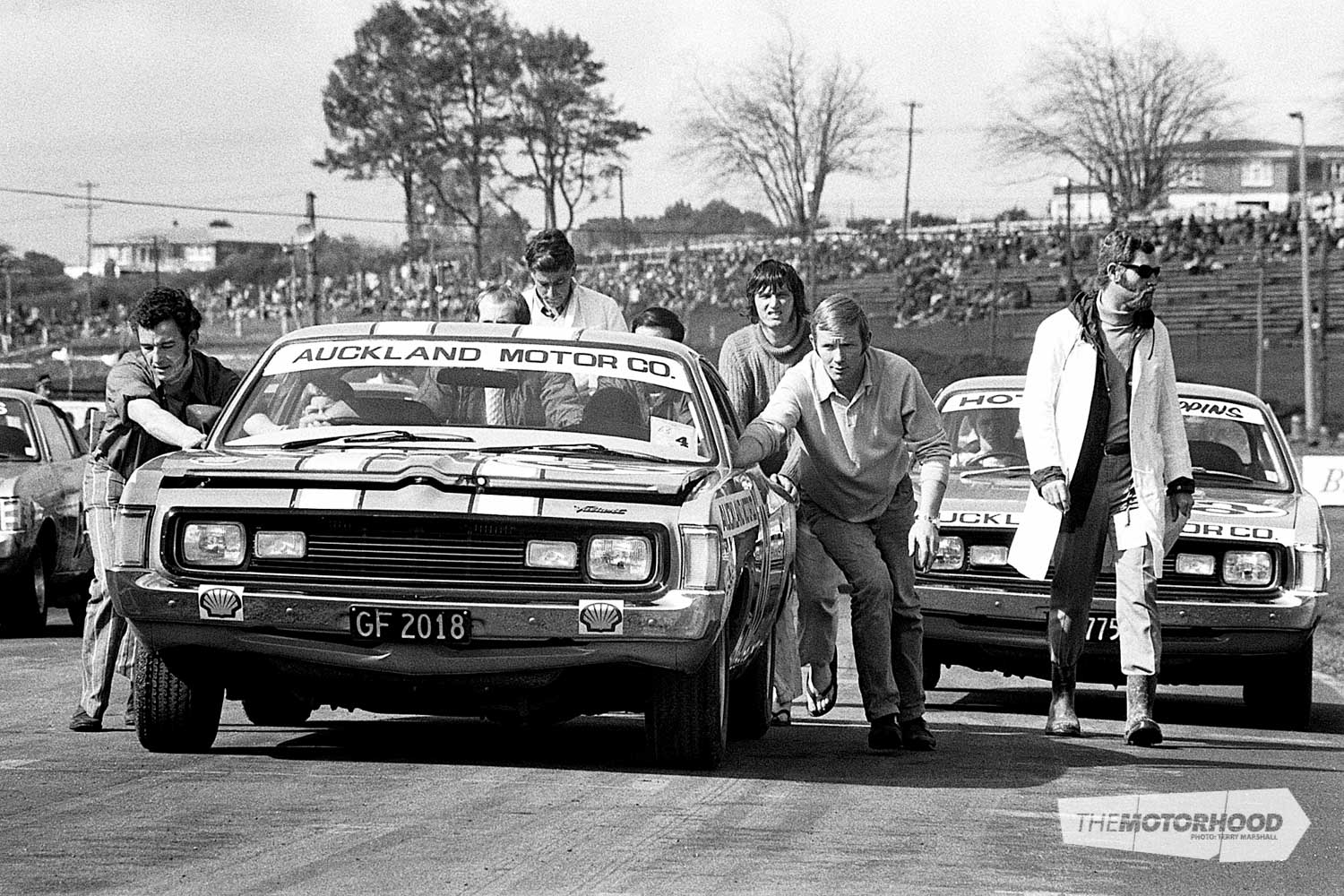

Of all Leo’s four wins in the B&H 500 — plus three more wins in the 1000km version — probably the 1970 500-mile race was his and Ernie’s greatest moment. Running the Valiant Regal V8 for the first time, Leo was comfortably in the lead when he lost control of the big car. He was negotiating the Loop section, and with the rain pelting down and fresh oil on the high-speed curve the Valiant got away from him, spinning into the wet grass of the infield where it promptly got stuck.

Many drivers would probably have thought ‘game over’, but Leonard was made of sterner stuff — a man imbued with a classic case of Southland grit! Or maybe he was more concerned about incurring his co-driver’s wrath regarding his indiscretion! Whatever, after pushing and shoving and trying to wheelspin his way out wasn’t working, he grabbed some sacks out of the car’s boot (those Southerners didn’t overlook anything in their car prep), ripped off the top part of his driving suit, stuck everything under the rear wheels, and the extra traction allowed him to get the car back onto the blacktop. Under the rules, no outside help was allowed in these circumstances, and the off-track excursion had lost Leo and Ernie several laps, dropping them back to 28th place. Their subsequent no-holds-barred drive back through the field to a magnificent victory has to be one of the truly legendary tales of local motor sport.

The mighty Charger’s glorious reign

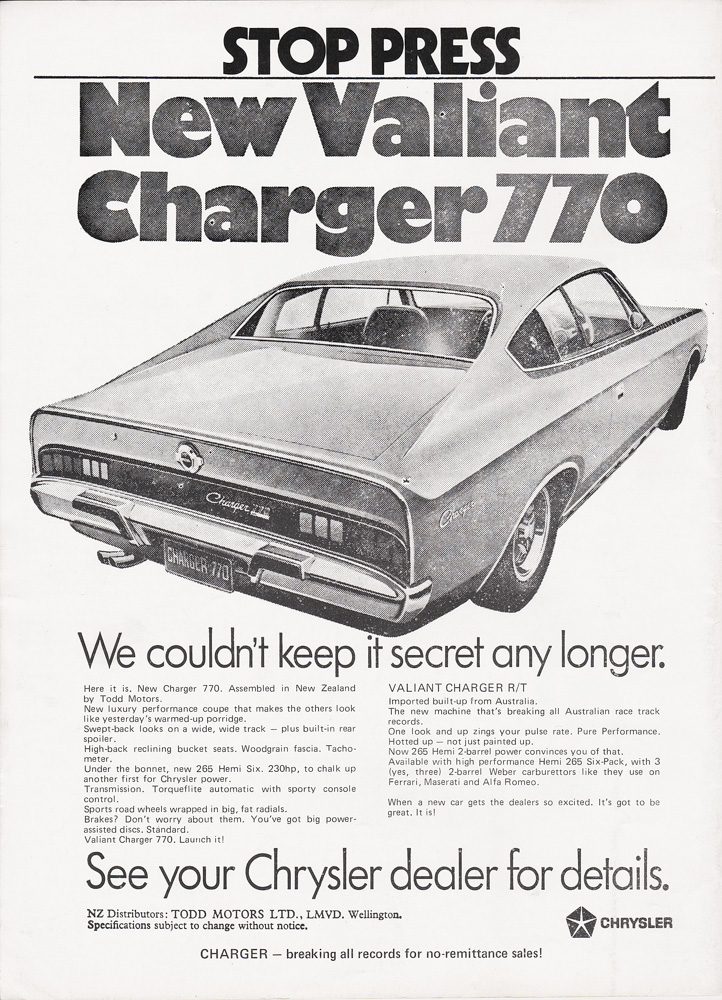

“Hey Charger!” was a marketing mantra from heaven — one that captivated the young car-buying fraternity in the early to mid ’70s. It signalled the arrival in New Zealand of the most sexy and potent sports coupé to ever be assembled on these shores. This was, in many ways, the high-water mark for locally assembled performance cars — although a case for the Mazda Capella RX-2 rotary coupé could be argued as well.

The locally assembled Charger, while not being an all-out racer like its R/T Aussie-assembled cousin, was still a formidably quick road car, and readily available here. Equipped with the 265ci (4343cc) Hemi and auto transmission, the Charger 770, as it was titled, was — to quote Mark Webster from his excellent book Assembly: New Zealand Car Production 1921–1998 — “A revolutionary car for local assembly (Todd Industries, Porirua) and demand was so strong, that a black market developed for those wanting to queue jump. This was the only time an Australian coupé was ever assembled in New Zealand. Trevor Turner was the man to thank, Todd Motors’ marketing director, who went out on a limb to include this model in the locally assembled range, to help give the Chrysler range a more sporty image here.”

Turner certainly got his sums right, and the Charger became a road and race-track legend throughout the ’70s and beyond. At $4975 dollars, base price, it certainly wasn’t cheap in 1972 terms, but considering the amount of bang for your buck it provided, it was the hottest locally-built iron to be had direct off the showroom floor anywhere in the country.

Chargers notched up a seven-victory winning streak in the Benson and Hedges series from 1972 to 1978, a marathon achievement for a machine of great charisma. Along the way it beat off challenges from some highly fancied opposition — including the Fiat 125T twin-cam (limited production factory specials), the Leyland P76 with its 4.4-litre alloy V8, the rotary-powered Mazda RX-2 and, later, the 5.0-litre Ford Fairmont V8. They all provided tough opposition and were worthy opponents but, ultimately, none were able to end the Charger’s winning streak.

Leo Leonard’s share of these wins was two more Benson and Hedges victories, one each in 1975 and 1977. He regarded his 1977 victory as one of the hardest, as he and Gary Sprague struck braking problems early on and had to fight back, driving to the car’s absolute limit in order to gain victory — shades of Leonard’s great 1970 triumph. The other great driving combination during the Charger years was, of course, Jim Richards and Rod Coppins, both skilled long-distance racers. They won in 1972 and 1973.

Leo also won a final time in 1981 at the wheel of a Fairmont V8, but the flavour of the race had started to change by then, leaning more towards limited production, high-performance saloons. This was the case of the SS Holden Commodore of the early ’80s, a locally assembled high-performance version, limited-production-run car built specifically with the intention of winning the B&H race. In reflection, the halcyon days and torrid battles between totally standard production cars, with all their limitations, had passed.

And with that passing, the true charisma and flavour of endurance racing — which required special skills to drive around the many limitations of basic ’60s and ’70s four-door family sedans over seven to eight hours of hard racing — was gone.

Are there any Benson and Hedges classics still out there?

Recalling those epic Benson and Hedges races rekindled my belief that these were truly New Zealand’s greatest auto races. A bold claim, but one that I believe is justified due to the many requirements those races demanded — from faultless car preparation to driving involvement that included maintaining race-winning speeds while conserving the machine’s mechanical well-being over a long period of time.

In wrapping this up, I find myself returning to a recurring thought — are there any genuine B&H survivors from the late ’60s and ’70s era still out there? Many of them would have ended up back on the sales lot the week after the race! Probably sales pitched as being a low-mileage example with one careful elderly lady driver!

It would be great to hear whether some or any cars with a genuine Benson and Hedges pedigree still exist? I know of a few Fiat 125Ts — due to their semi-exotic origins — that have been restored or maintained. Possibly a few of the Datsun SSS ‘special racing performance versions’ offered by Dennis Marwood’s Performance Developments — complete with their Dell’Orto side-draughts and other drama — still exist, and maybe one or two that raced in the ‘great race’ are still out there? Then there are the Chargers — it’s conceivable that some of them might have survived.

Much less likely are the chances that any of the Vauxhall Victors, Zephyr V6s, and Valiant V8s escaped the junkyard or the crusher, let alone other, more humble utilitarian offerings like Datsun 180Bs and 1600s, Ford Escorts and Toyotas that raced in anger at New Zealand’s ultimate racing event. However, you never know — and if you know the whereabouts of one of the veteran B&H saloon racers, I’d certainly be interested in hearing from you.

Photos: Terry Marshall / Gerard Richards / Euan Sarginson / Steve Buchanan

This article was originally featured in a previous issue of New Zealand Classic Car. Pick up a copy of the edition here: