data-animation-override>

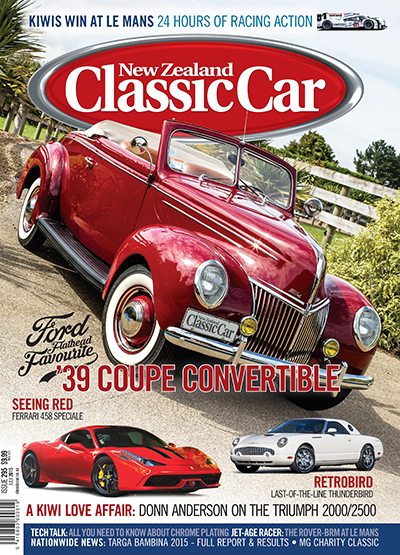

“Donn Anderson recalls the 15-year Kiwi love affair with the Triumph 2000/2500, a car that did better here than anywhere else in the world”

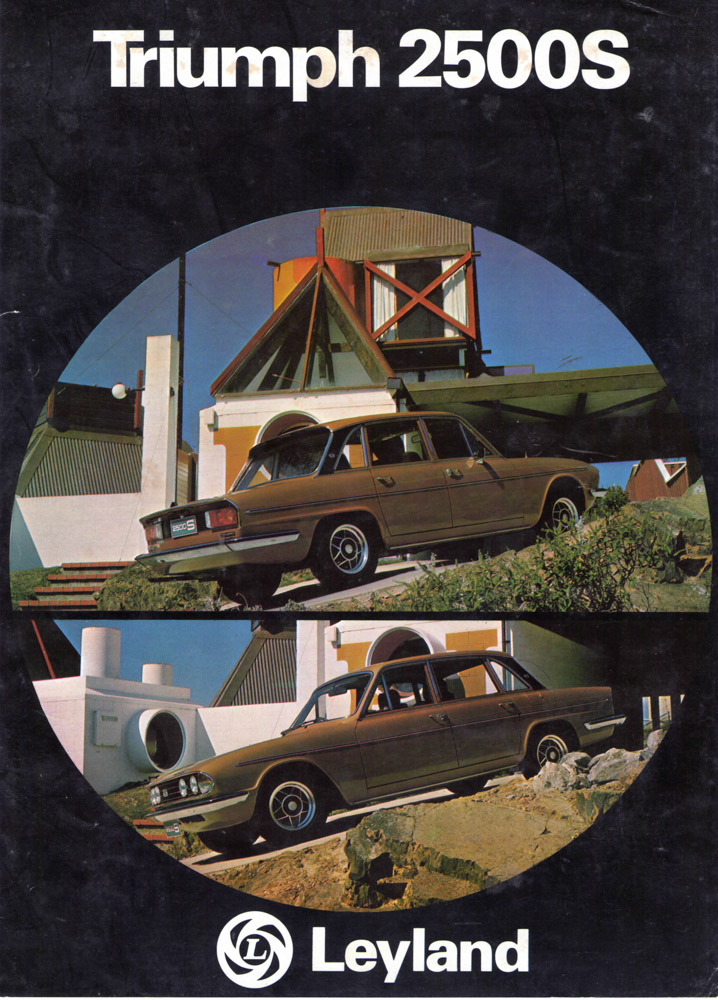

Solid, safe, conservative — owners were likely to vote National, wear a tie to work and have a beer at the RSA on a Saturday afternoon. This was the profile of the Triumph 2000, and the 2500, cars that remained a truly solid automotive contender on the New Zealand market during the latter half of the ’60s and throughout the ’70s.

In the Swinging Sixties, to have a Triumph 2000 in your garage meant you had made a success of your life, were doing somewhat better than the average bloke and had fine taste to boot. The distinctive-looking car was also deemed to be a cut above mainstream Zephyrs, Falcons and Kingswoods. Whether all this is true is neither here nor there — the simple fact is that the Triumph commanded a position in New Zealand unmatched by any other market where it was sold.

And there was another dimension to the popular Triumph — while the car’s international motorsport successes were down to creditable second and fourth overall placings with the 2.5-litre PI version in the gruelling 1970 London to Mexico World Cup Rally, the model was also a consistently good performer in New Zealand regularity trials. The Triumph’s power-to-weight ratio would never make the 2000 a force in production circuit racing, although it achieved a measure of local success that wouldn’t be repeated elsewhere.

Track Triumphs

Alan Woolf, who won MotorSport New Zealand’s distinguished service award in 1995, was a long-time campaigner of the British car, entering an early Triumph 2000 in the 1966 Wills Six Hour production race at Pukekohe, with co-driver Jo Hayes. The following year he was back, this time sharing the drive with Bill Beasley in an effort that saw the pair finish 13th overall. Woolf and Beasley finally cracked it with the 2000 in the 1969 Benson & Hedges 500 Pukekohe race, winning the 2.5-litre class. The pairing achieved a third in class at the same event in 1970. Woolf went on to race a 2.5 PI, sadly injuring his back when he rolled the Triumph at Bay Park.

John Kay and Stan Curtis achieved 7.5l/100km (37.7mpg) in the 1964 Mobil Economy Run in what was the first competition outing for the model in New Zealand. Meanwhile, the 2000 made its local racing debut at the 1965 Wills Six Hour in the hands of Beasley and Hayes, but they were out of the running with a blown radiator hose.

The more powerful 2.5 PI was always going to be a more logical track contender, as Jim Richards and David Oxton proved in the 1971 B&H 500, finishing an excellent third overall while also winning their class. Neil Johns took tenth place in the 1972 Heatway international rally in his 2.5 PI, and the similar Triumph of Neville Crichton and Rodger Anderson won its class and was ninth overall in the B&H 500 event the same year. Johns, with navigator Glen McLean, took a fine third overall with his 2.5 PI in the 1969 Silver Fern rally, and the pair went even better in the 1970 event, when they were second.

Trials Triumphs

Yet the Triumph 2000’s record sheet in trials was perhaps even more impressive. Kerry Lay’s 2000 won the 1968 Castrol Gold Star trial in the North Island, finishing second only to Blair Robson’s 3.0-litre Zephyr for the season, while the 2000 of Ron Perillo finished eighth. Perillo won the 1970 Levin Gold Star trial and the Tisco Gold Star event the same year. Another Triumph 2000 in the hands of Ross Haldane won the Tisco event in 1971, while Noel Curtis joined the trials competition in his Triumph 2000.

Curtis won the Otago Gold Star trial and Canterbury Gold Star, emerging winner of the 1971 Gold Star trials and rallies championship for the season after Perillo’s Triumph dropped a valve with just 80km to run in the 644km (400-mile) final round. Haldane took third overall, making it a one-two-three for the Triumph 2000.

Haldane continued to campaign his 1965 model 2000, winning the 1972 Tisco rally and Northern Sports Car Club Castrol Gold Star, despite brake failure. Neil Johns took his 2.5 PI to tenth in the 1972 Heatway Rally, but by this time newer, smaller rivals were making the Triumph uncompetitive in high-speed events.

That wasn’t the case for New Zealand buyers, who were taking to the car in even great numbers during the ’70s.

Triumph tale

Enthusiasm for the Triumph began right from the unveiling of the Giovanni Michelotti–styled 2000 — a real advance on the old Standard Vanguard. Rover may have stolen some of Triumph’s thunder by announcing its radical 2000 sedan in England in October 1963, one week before the Triumph broke cover, but the latter boasted the advantage of six-cylinder power, and it would be five years before Rover introduced its V8-powered version of the P6.

UK production of the Triumph did not commence until early 1964, with the first examples arriving in New Zealand later the same year.

Typical of local buyers was my father, who wanted to trade out of his Ford Zodiac MkIII and looked at both the then-new Triumph and Rover. The Rover 2000 was more difficult to acquire, since it remained a fully imported model until 1968, when a local CKD programme was implemented. At £1900 ($3800) the Rover also cost more than the £1485 ($2970) Triumph. However, it was the attraction of the six-cylinder engine that finally enticed my father, and a locally assembled Triumph 2000 MkI won the day. His passion for the model resulted in the later purchase of a new MkII.

In 1964 a new Zephyr 6 retailed for £1228 ($2456) so the Triumph was never considered cheap — but this didn’t deter buyers.

Triumph tattle

Australia and South Africa ran a local-assembly programme for the 2000, but New Zealand was arguably the most successful export territory. A limited number were assembled at the Standard–Triumph plant in Christchurch before Motor Assemblies Ltd, the manufacturing division of Leyland Motor Corporation of New Zealand, bought the uncompleted building at the Nelson cotton mill site in 1964, and began assembly of the 2000 MkI in October 1965. Some 7070 MkI saloons were built at Nelson until December 1969, with assembly of the MkII commencing the following month. Between October 1965 and March 1979, the Nelson plant assembled 29,903 examples (of which 22,833 were MkIIs), the most popular version, the 2500TC MkII, accounting for 10,776 units.

From a classic-car perspective, the most collectable models are early 2000 MkIs or the top-shelf MkII 2.5 PI, although the number of PI sedans made locally is unclear.

Remarkably, while production in the UK ended in 1977, New Zealand demand remained so high the car stayed in production for a further two years. New Zealand accounted for nine per cent of all Triumph 2000/2500 models (324,652), making its penetration on a per capita basis the highest in the world.

By 1967 the manual 2000 cost $3210, or $3462 when specified with the popular three-stage BorgWarner 35 automatic option. The four-speed manual featured a General Motors–type inertia lock synchromesh on all forward gears, and was identical to the unit used in the TR4A sports car.

A few built-up estates ($4042) were imported, but were only available if customers had an overseas funds deposit.

Triumph technical

The first of the MkII versions were priced at $3877 ($4204 for the auto). The MkI 2500 PI was built in the UK, but this model came to prominence in MkII guise, where its 98kW (132bhp) gave a welcome boost to the car’s performance although the Lucas fuel-injection suffered from reliability issues, including fuel vaporization in summer temperatures.

MkII models were distinguished by a longer nose section, mirroring the Triumph Stag sports car, a longer tail and revised interior. Overall length increased by 225mm to 4650mm. Wheelbase, width and height remained unchanged, but the car was given wider wheel tracks, and aerodynamics improved. In 1970 half of all 2000 sedans built in Nelson were manuals, with an additional 15 per cent fitted with a manual gearbox and overdrive, leaving just 35 per cent as automatics.

In 1971 the 2500 PI was just on $5000, with the 2500TC about $700 cheaper. The fuel-injected model was phased out early in 1976, and the last of the 2500s in 1979 were $11,972 or $12,674 for the auto. The 2500S model introduced in 1978 came with a heated rear window, tachometer, power steering and sports wheels.

When Neil Johns was campaigning his 2.5 PI he fitted a TR6 camshaft with more overlap, adjustable shock absorbers and a limited slip differential from his faithful Triumph 2000 MkI in which he did well over 50,000 miles (over 84,467km). The 2.5 PI had no rattles or clunks after the rugged roads and pounding of the Heatway rally.

Triumph testing

Rewind to 1964 and the launch of the 2000 with an individual specification that included a well-sorted independent rear suspension — and when I tested one of the first locally assembled 2000s 50 years ago, the standard of finish was excellent and the car’s handling was deemed far better than rival sixes of the day.

The market quickly warmed to the car’s Italian styling and British embellishments such as wood cappings on the dashboard and doors. Buyers compared the car to the more costly Jaguar 3.4, Daimler 2.5-litre, Humber Hawk and Wolseley 6/110 plus, of course, the Rover 2000 and liked the car as it was not too large or ostentatious, representing a fine balance between austerity and excessive luxury.

Using the Vanguard engine — the only direct legacy from the old Standard — power was upped from a modest 80bhp (60kW) to 90bhp (67kW), with a higher compression ratio and a pair of Stromberg 150 CD carburettors.

There were changes to the cylinder head and improved breathing, and the engine was inclined 10 degrees to the right. When the MkII came on stream the range was extended with the 106bhp (79kW) 2500TC and similarly powered 2500S. As the first British saloon fitted with fuel injection, the car really came alive with the arrival of the 2500 PI option, although the long-stroke pushrod engine could hardly have been classed as cutting-edge technology.

Minor cylinder-head modifications were applied to the 2000 MkII that developed the same power as its predecessor, but ironically overheating and head problems were frequent when the car first arrived here.

My father’s MkII was not as reliable as the MkI that he ran for five years, coming to a halt with a leaking clutch cylinder when just two days old. The clutch continued to give trouble, being replaced within the initial 1600km, only to be replaced a second time. This same car was also dogged with oil leaks fore and aft of the gearbox, plus an intermittent misfire finally traced to a faulty ignition coil.

There were numerous other problems with this MkII, and I was amazed my father still considered the Triumph a top-quality car — but hark at the devaluation of money and the seemingly frugal costs of running a new Triumph 2000 in 1972: the annual licence was $21.40, a six-monthly warrant of fitness cost $2 and comprehensive annual insurance was $37, while depreciation amounted to just over $700 for the year.

When testing the MkII model on local roads in 1970, a complaint about performance prompted British Leyland to provide me with a second car, which had a slipping clutch. The problem was resolved with a third 2000, but my experience raised raised questions over reliability.

The 2000 marked the end of the Standard name, and was seen on the home market as a modern counterpart to the 2.0-litre Triumph Renown that ran from 1946 until 1955. Half a century ago the Triumph 2000 was reckoned to hold golden prospects with its modern technical specifications, full equipment, roominess and pleasing proportions, and to a large extent it achieved these aspirations. Prime Minister Robert Muldoon had at least two of these Triumphs, including a blue 2500 and a white 2500S.

Today’s BMW 3 Series and Mercedes-Benz C-class sedans are less affordable equivalents to the long-gone Triumph 2000 but, in a far less restrictive modern era, the German challengers can scarcely hope to make the same impression as the British car.

New Zealanders enjoyed a 15-year love affair with the Triumph 2000, and these cars are still remembered with warmth by many motoring enthusiasts.

This article was previously published in New Zealand Classic Car Issue No. 295. You can buy a print copy or a digital copy of the magazine below: