data-animation-override>

“A simple formula is often the answer, as BMC envisaged with the Austin-Healey Sprite and MG Midget. Donn Anderson remembers the game little sports car”

Forty-one years ago, the MG Car Company, then part of British Leyland, had a dispute with the MG Car Club in the UK. While the club reckoned that the marque’s jubilee celebrations should have been recognized in 1974, the company ruled it to be the following year, since that was when MG production began in earnest.

The Brands Hatch grandstands may have been sparsely populated on a day to toast 50 years of MG in 1975, but the pits and race track were jammed with enthusiasts and scores of MGs, old and new. Several New Zealanders were there, including Denny Hulme, fresh from his Formula 1 retirement; McLaren director and team manager Phil Kerr; and Bill Bryce, one-time Levin commentator, radio journalist, and co-owner of a small airline business with Chris Amon. Denny cut his racing teeth in New Zealand with an MG TF, and was in the process of restoring the MG back in Rotorua.

Kerr was driving an immaculate MGA Twin Cam in a fantastic parade of race and road-going MGs, and Bryce had his equally impressive MG TC out for a run. “I can’t believe I used to race one of those MGs — and we used to think we were going quick,” Denny told me. Even then, there was some doubt about the future of the sports-car brand, although Bob Ward, the then head of MG, insisted that there would definitely be MGs in 50 years’ time. I wonder what he would think about the situation today?

I spotted Michael Crawford sitting on his own in the main grandstand, and asked him what his interest was in MGs. “I just like them,” said the actor, singer, and comedian, who otherwise played the hapless Frank Spencer in the Some Mothers Do ’Ave ’Em television series. I know the feeling. My brother and I grew up on a diet of MGs and were keen members of the MG Car Club in Auckland. In the ’60s, there was no way to buy a new MG unless you had overseas funds, so we invariably bought second hand in a market in which vehicle depreciation was almost non-existent.

Factory visit

On a soaking wet day in July 1968, I visited the MG factory at Abingdon, near Oxford, and was struck by the compact dimensions of the plant, which looked not much larger than the long-gone Dominion Motors Morris complete-knock-down (CKD) operation in Newmarket, Auckland. Even then, most car factories were automated, so it was surprising to see body shells pushed down the assembly line by hand. Public relations man and writer Stuart Seager, who showed me through the factory, said that, in spite of this, productivity was equal to the massive Morris assembly division at nearby Cowley.

In the late 1960s, the 1100 staff at Abingdon were turning out 1100 MG sports cars a week, with 85 per cent of production bound for North America. An old-time touch was the 11-kilometre road test that every MG off the line underwent through the Berkshire countryside. At the time, MG was the world’s largest manufacturer of production sports cars, and the main problem was not selling units but adapting them to suit differing markets, particularly the US.

My introduction to the brand had, unsurprisingly, come via the smaller, less expensive models, and, to young enthusiasts, the MG Midgets and Austin-Healey Sprites had special appeal. However, the first of the Midgets dated back to the M-Type in 1929 that came with a little 847cc engine and a mere 15kW of power — that’s 20bhp. Other Midget milestones were the J2 in 1932, PB in 1933, TA/TB/TC in 1936, and TD in 1950. When the TF replaced the TD in 1954, it became the last of the traditionally styled Midgets. TF production ended in 1955, leaving MG without a Midget model for six years before the handsomely shaped modern-generation car appeared.

Affordable

MG Midgets and Austin-Healey Sprites were a junior, low-cost way of securing sports-car ownership and were invariably reliable and cheap to run. Next step up was the MGB, which I and my brother, Rodger, both progressed to, but the smaller Midgets and Sprites provided that crucial first step on the ladder to fresh-air motoring. British Motor Corporation (BMC) built almost 50,000 MkI 948cc Bugeye Sprites, and, in the US, keen owners were racing the car just three days after the launch date. It was commonplace for 30 or so of the little cars to scrap for a corner in North American races.

There was a delightful simplicity about the original Sprite, with the protruding headlights mounted atop the large bonnet section that was heavy to lift but offered great accessibility — an engine change could take little more than 20 minutes. Sadly, Bugeye ownership passed me by, and my first Sprite was a light-blue MkII with sliding windows, followed by a red 1962 Midget.

Brother Rodger experimented with a white Midget 1098cc, fitting a supercharger that had been adapted by Kumeu tuner Ted Thompson. Fitting a Shorrock blower presented few problems and boosted power by 36 per cent, resulting in a marked improvement in acceleration.

Rodger ran the supercharged car at one Pukekohe national meeting, but more successful was his dark green 1098cc Sprite with wind-up windows, prepared by Mission Bay Motors and bored out to 1220cc. This car had special extractors, a modified exhaust, and lively camshaft and was lowered and had modified shock absorbers, different spring rates, a limited-slip differential, and fatter anti-roll bars front and rear. Cornering was vastly improved by the fitment of 13-inch Dunlop racing rubber to the wire wheels.

At a Pukekohe national meeting in November 1966, Anderson finished second in a handicap event to Jim Boyd’s much faster Lycoming Special, and, in the Half Hour sports-car feature on the same circuit a month later, the Sprite finished second to a Daimler Dart in the production class. With the windscreen and surround removed the Anderson Sprite took second in the sports-car production category at the 1967 Pukekohe Grand Prix and won the handicap event at the Levin Tasman meeting the same month. When the car was reverted to standard and sold, Anderson said it was still remarkably quick.

Modifying these cars (and Minis, of course) in the ’60s was easy enough, and carried the blessing of BMC’s special-tuning department, which produced tuning guides and offered a huge array of approved go-faster equipment. The Midgets and Sprites were available with optional close-ratio gears, strengthened disc wheels, competition camshafts, lightened valve gear, special pistons, nitrated crankshafts, stiffer shocks, and larger SU carburettors.

Jack Brabham went one better in 1961 when he installed a 1216cc overhead-cam Coventry-Climax FWE engine into a Midget, boosting power by 80 per cent and turning the little MG into a giant-killer. The Climax engine was about 20kg lighter than the BMC power plant, and the end result was a top speed of 180kph, instead of the standard car’s 140kph, and a sharp improvement in acceleration.

Remarkable survival

Almost a quarter of a million Midgets were made from May 1961 until December 1979, while Sprite production ended in 1971 with a tally of 129,000. Most were exported, but of the 74,000 Midgets sold in Britain, a recent analysis revealed 7026 of them are still registered for use on the road — a remarkable survival rate of almost 10 per cent.

However, it is estimated that fewer than 400 MkI Sprites remain operational. Most Spridgets were built at the MG plant in Abingdon, but the Australians implemented a CKD assembly programme for the sports car at the Enfield factory in New South Wales; New Zealand, however, imported new Midgets and Sprites from Britain.

Applauded as the most characterful British sports car made since World War II, the Bugeye, or Frogeye, launched in May 1958, and was the first mass-produced open sports car with body and chassis constructed as a single unit. The front metal assembly, including bonnet and wings, is a one-piece unit, hinged at the back. To improve rigidity, there is no opening boot, so the load area is assessed through the rear of the cockpit. There are also no exterior door handles, so the Bugeye cannot be locked, and even a tacho was extra.

In 1961, Car & Driver magazine in the US described the Sprite II as “everything the MG TD was 10 years ago”. Significantly, the middle sections of the MkI Midget and second-generation Sprite are identical to those of the Bugeye, so, while the newer model looks entirely different and longer, it shares much with the original car, including the same 2030mm wheelbase and overall length. Many of the styling cues of the Sprite II and generation-one Midget — particularly the rear-end treatment — were adopted for the MGB that followed in 1962. Yet, it’s a wonder that this second-generation Sprite and the MkI Midget looked so good, since one end of the body shape was styled at Longbridge while the other end was crafted at Abingdon! And, to make matters worse, the heavies at BMC told the respective stylists not to communicate with each other until the final stages.

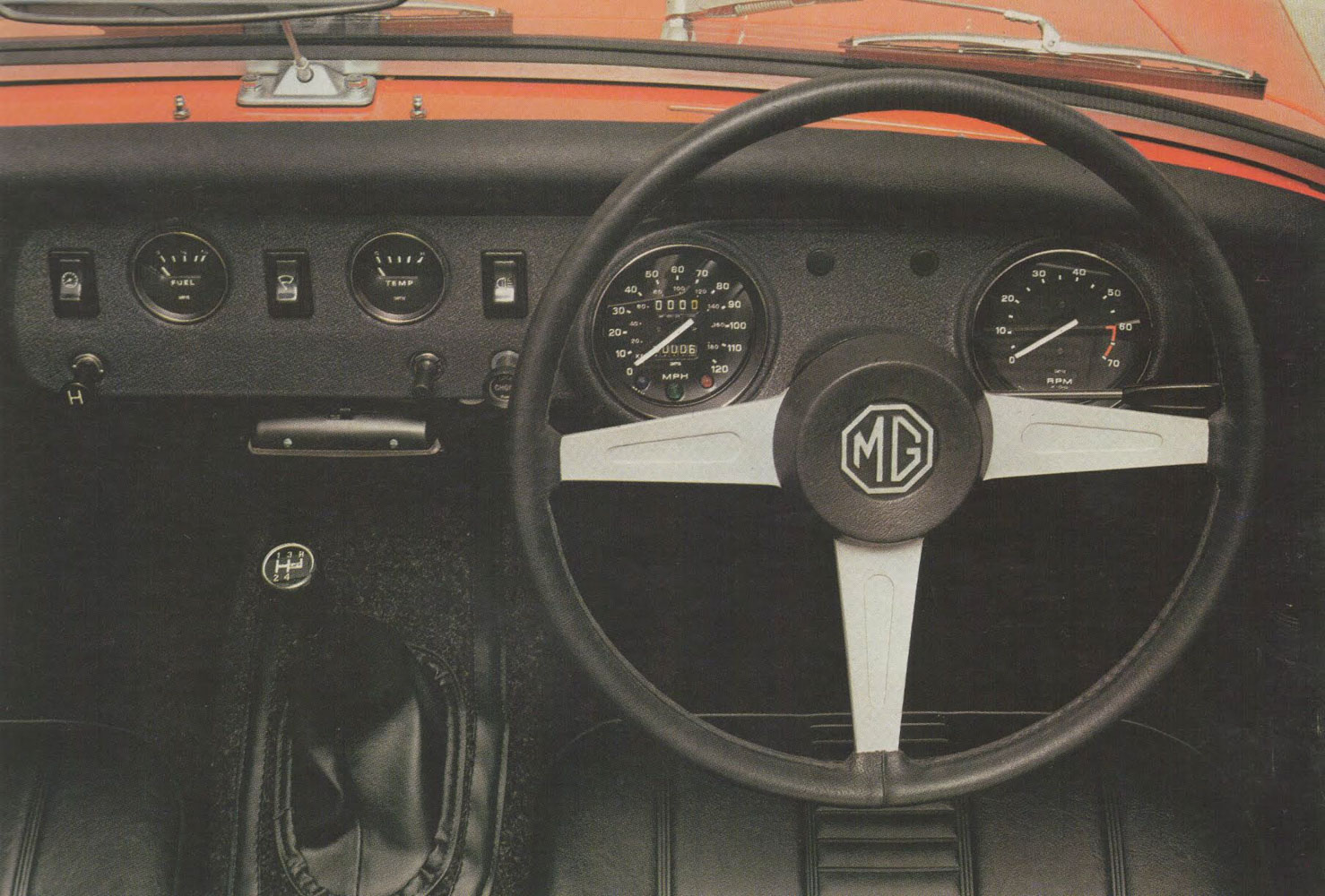

You only need to clamber into the tight cabin to realize this is a small, Mini-size vehicle — and the original model’s overall body length of 3370mm (or 3480mm with optional bumpers) extended only to 3500mm for the last of the chrome-bumper models. When the awful black rubber bumpers were fitted to the last models, the car measured 3580mm.

The car made use of BMC’s parts bin, with the overhead valve, pushrod A-Series motor lifted from the Austin A35 and Morris Minor 1000, a Minor rack-and-pinion steering, and A35 front suspension. With the addition of twin SU carburettors, power output was a modest 32kW, and this small 948cc engine was retained for the first of the MkII Sprites/Midgets that followed three years after the Bugeye. In October 1962, the arrival of the longer stroke 1098cc engine meant a power boost to 42kW, front disc brakes, and a wire wheel option. Other improvements included a larger clutch, baulk-ring synchromesh, and improved trim. The MkIII Midget (and MkIV Sprite), in October 1966, heralded arrival of the 1275cc engine with 48kW, but this was not the more specialized Mini Cooper S power plant, and it ran a normal forged-steel crankshaft in place of the tougher, more specialized nitrided-steel crank.

The 1.3-litre engine meant 10 per cent more power and an 11-per-cent boost in torque. The soft-top hood was now permanently attached, instead of being arranged with detachable hood irons and covering. Popularity of the model remained strong, with production running at 350 cars a week. Detail changes in 1970 comprised new chrome bumpers, a revamped grille, black side winders, Rostyle steel wheels, reclining seats, an uprated heater, and cabin enhancements.

MG enthusiasts were hardly cheering when the final changes were implemented in June 1975, with the replacement of the venerable A-Series engine with the fractionally more powerful Triumph-designed 1493cc unit used in the Spitfire and discontinued Triumph 1500. But the car’s appearance was damned by the fitting of ugly black polyurethane bumpers to meet North American safety legislation, while the rounded rear wheel arches that had been introduced four years earlier reverted to the flattened-style arches of older versions. Overall ride height was increased, again for US safety reasons, but, in fact, it made the car less agile and simply inferior when it came to handling. Unsurprisingly, enthusiasts invariably favour chrome-bumper models from 1972 until 1974.

New Zealand road test

Seabrook Fowlds, the Auckland Austin agent, provided my first MkII Sprite 1098cc road test in 1963. At that time, the new retail price was $1658, and, two years later — when I drove a Dominion Motors–supplied Midget with wind-up windows — the price had risen to $1810, with the Austin equivalent a few dollars less. By 1969, the MG had risen to $2693, $3200 in 1973, and $4500 by 1975, the last year in which the model was imported new into New Zealand. The first of the 1491cc Triumph-engined Midgets in September 1974 were priced at $3900.

The car had always been fun to drive, but, in 1964, was improved by deleting the quarter-elliptic rear leaf springs in favour of half-elliptic springs, improving rigidity and axle location. This new design was not only lighter but also resulted in a better ride with diminished axle hop over indifferent surfaces, and less-sensitive steering. Engineers were able to eliminate much of the body stiffening required by the old suspension. So, while the new window glass and window lifts were clearly heavier than the old detachable widescreen models, the weight saving in the suspension meant that the newer car was only fractionally heavier than its predecessor.

The light rack-and-pinion steering had long been praised for being quick and accurate, with little more than two turns of the steering wheel from lock to lock. In its 1963 test of a MkII Sprite, the American Road & Track magazine said, “The Sprite can be driven through a series of fast S bends with only the slightest movement of the wheel and although the tail tends to drift out, from body roll, on entering a curve, it stabilizes almost immediately and gives the feeling of a completely neutral steering car.

“Due to its responsiveness and neutral handling it is an excellent car for the beginning sports car driver; and with the nominal initial cost and good fuel economy it is also ideal for the impecunious.”

As a result of British Leyland rationalization, Sprite production ceased eight years before that of the Midget ended, and a larger fuel tank was fitted to Midgets after January 1972. Even though Midget production stopped in late 1979, cars were still being sold in 1980 — 22 years after the first Bugeye Sprite appeared. Today, a healthy number remains on Kiwi roads, a sure sign of the affection felt for a rather special car.