data-animation-override>

“When rally champion Marcus van Klink heads out to classic rally events to battle his fellow competitors, most of whom are driving Ford Escorts, he does so in fine style driving this very potent Mazda RX-7”

Marcus’ weapon of choice has been questioned by many and still raises a few eyebrows, but when we delved deeper into what makes this talented rally competitor click, we weren’t at all surprised. Marcus is certainly no stranger to rotary-powered vehicles. His father was always into cars, owning another modern Japanese classic — a Datsun 240Z, while his mother once owned a Mazda RX-3, and his grandfather had a Mazda RX-4.

Moving through the years, Marcus remembers his first road car was a Toyota SL coupé followed by his first rotary-powered car, a Mazda RX-2. From there, he moved on to a turbocharged Series 1 RX-7. When he married his wife, Jemma, the cars were sold to make way for a new plumbing business — and it was only after many years of hard work that he was able to reignite his passion for vehicles.

Once he could afford it, Marcus purchased a Mitsubishi Evo VII, and immediately began to compete in club days at Ruapuna before buying a Targa-spec Evo III a year later, entering the Dunlop Targa in 2005. This was Marcus’ first true rally-type event, and out on the Targa special stages all seemed to be going according to plan. He was placed in the top 10 on the second-to-last day until he went off the road at 180kph, totally destroying his car. Not one to give up easily, Marcus wasted no time in building another Evo III, and went back the following year for another shot. Alas, his second Targa ended with a similar result to his first.

Gravel rash

During the same period, Marcus also purchased a Datsun 1200 coupé and started competing in some shingle events, which he really enjoyed. His first shingle rally was the Canterbury Rally in 2005 and, despite finishing 53rd out of a field of 75, he actually ended up third in class and hasn’t looked back since. Marcus continued to rally the Datsun the following year, taking out the 1300cc class in the Mainland Rally Series.

However, by now, his old 1200 wasn’t quite doing it for him as far as pace was concerned, so he decided to build something a little quicker and more robust for rally conditions — a Toyota AE86. This he campaigned in the 1600cc class. Marcus won his class for two consecutive years before deciding to repower the Toyota with a 2.2-litre Altezza Beams engine coupled to a six-speed sequential gearbox. Marcus still owns this car today, and he runs it twice a year at club rallies.

In 2009, he purchased the ex–Regan Ross Mitsubishi Evo VIII, and entered the New Zealand Rally Championship (NZRC). After some encouraging results — and quite a few roll-overs — Marcus decided he really wanted to build a fantastic two-wheel–drive historic rally car to compete in the NZRC.

Rally rotor

Marcus’ decision to build a Mazda RX-7 was indeed simple. He didn’t like the looks of Ford’s ubiquitous Escort MkII, so the obvious choice was to build an RX-7 — but not just any old RX-7. Marcus wanted it to be as close as possible to the Group B car that competed on the international rallying scene for a short time in the ’80s.

He was encouraged by the fact that most of his friends and colleagues thought building a Mazda RX-7 rally car was a good idea. However, his friends at Palmside Automotive in Christchurch were somewhat hesitant to build a rotary-powered vehicle. Despite these early misgivings, though, and following plenty of heated discussion, many hours spent surfing the internet for ideas, and searching out photographs of RX-7 rally cars from old books, they managed to piece the puzzle together. Armed with their new-found information, the build began.

Marcus was able to acquire a good straight car via a local auction website, and Brent Buist from Palmside Automotive made a start on the project. The build progressed quickly, with the RX-7 completely stripped to bare steel and sandblasted before fabrication started.

Marcus was able to acquire a replica of the original Group B body kit from Europe through a friend who, coincidentally, was also building a Group B RX-7 at the same time. Copies being copies, fitting this body kit required a lot of time-consuming modification work to make it attach correctly to the existing body, as nothing seemed to line up.

Once the reluctant body kit had been fitted, a roll cage was fabricated and installed along with a custom-made dry-sump tank, the latter identical to the original tanks that were used by the Group B cars in the ’80s. The oil cooler was fitted into the rear wing — road cars have their coolers up front.

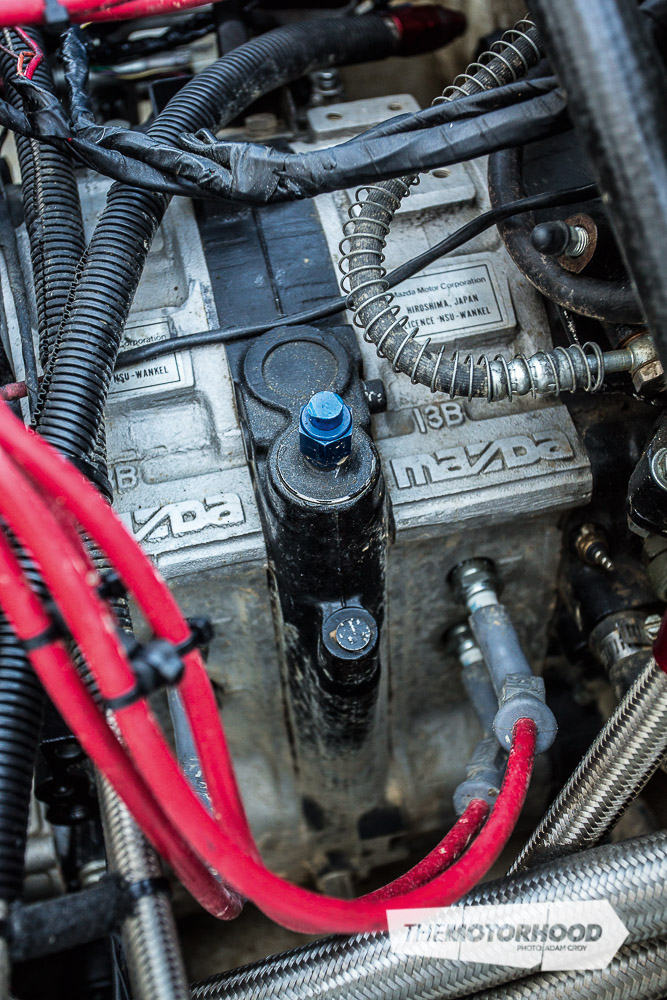

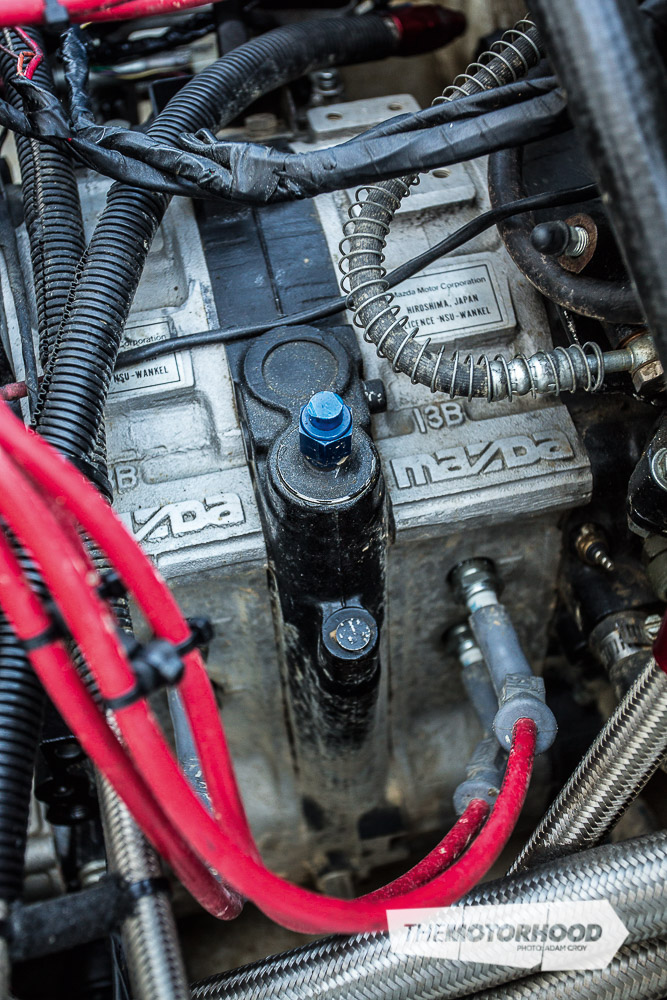

Marcus installed MCA coilover suspension with AP Monte Carlo four-pot brakes throughout. The engine is a factory Mazda 13B peripheral-port Wankel running a Mazdaspeed dry-sump front cover, and pumping the oil through to the rear oil cooler while fuel is fed through a Jenvey 48mm throttle body and Link ECU. The gearbox consists of a Modena dog box in a Mazda case — a combination that has proved to be absolutely bulletproof.

Apart from the body kit, all the other parts for the project were sourced in New Zealand through Palmside Automotive, which has also assisted Marcus to maintain the car throughout its rallying life so far. Given Al Marsh Rotorsport built the engine, this fine machine is an all-Christchurch construction.

Hot rotor

Marcus reckons his Mazda is, quite literally, a very hot car to drive on a rally.

Because of the rotary engine’s dry-sump configuration, the oil and fuel lines run through the car’s interior making the cockpit uncomfortably hot, and there’s also quite a bit of heat that emanates from the exhaust system — all of which makes competing in the RX-7 even more challenging.

The upside, according to Marcus, is that the RX-7 handles like a dream on gravel roads — “It is just fantastic, it’s very stable at high speeds and pretty good all round,” he says.

These handling characteristics must be comforting, given that, in most rallies, speeds can reach between 180 and 195kph. Although Marcus consistently opts not to push the boundaries any further for fear of breaking the car, he did reach an impressive 208kph on a long straight at Rally Wairarapa.

He reckons he could have pushed a little harder, but was concerned about the engine. Marcus explains he’s not able to hold it flat because of the revs, so he has to compensate by left-foot braking to keep the load on. Without the load, at those high revs he would more than likely run the risk of blowing an engine, or having something major let go.

A stage in the NZRC can run for anywhere from five to 30 minutes, and on some occasions even longer, so the engine has to be perfect. During a rally, when competing from stage to stage, no one else is allowed to work on the car except the driver and co-driver, unless it is in a designated service area. While Marcus and his co-driver, Dave Neill, are capable of attending to basic engine repairs, they’re certainly not mechanics, so it’s essential the car and its rotary engine are perfect, and capable of running trouble-free for long periods of time.

In terms of handling capability, Marcus explains that the RX-7 performs better on tight twisty roads. He actually prefers corners, as he’s a bit shy of the fast stuff. Most people would think a Mazda RX-7 would perform poorly on a tight and twisting forest stage, but, in reality, it’s actually quite the opposite: the RX-7 makes short work of the tight stuff due to lots of power on tap and a very tall first gear. One minor handicap is that the RX-7 struggles in wet conditions, but that’s a small price to pay considering the car’s overall performance.

Of more concern to Marcus is the thought of crashing — the cost of repairing the Mazda’s carefully modified fibreglass panels could be horrendous. However, he remains pragmatic and fully aware that such a possibility comes with the territory, and is part and parcel of the sport. Mind you, it does slow him down a wee bit — although he has come very close to rolling the RX-7 over once or twice.

“It’s always on Dave’s [the co-driver] side, as the left rear seems to get hammered more than the rest of the car,” says Marcus, jokingly.

Despite this, Dave is very well organized and makes sure they get to the right place at the right time, both before and during a rally. As Marcus puts it, “We make quite a good team in the car, and it’s not the easiest car to co-drive in because it is incredibly small and low to the ground, so he does a great job to cope.”

Rotary passion

One of the disadvantages of driving a rotary-powered rally car is the lack of engine braking available — something easily sourced from a reciprocating-piston engine. Marcus has adapted his driving style to suit, and he’s obviously done a very good job of it, as his stage times haven’t been affected at all. In fact, he logged several stage records during both the 2012 and 2013 rallying seasons.

Marcus reckons the trick is to apply the brakes earlier for corners to compensate for the lack of engine braking. That lost time is quickly regained because of the power of the rotary engine and the sheer acceleration out of bends that’s possible. Another reason the RX-7 can be difficult to drive is because Marcus and his co-driver, Dave, are essentially sitting in rear of the car — and that explains why the Mazda’s headlights are permanently in the ‘up’ position — so Marcus can see the front of the car over its very long bonnet!

Under that bonnet, the engine will have worked tirelessly throughout the entire season after which it will receive a well-deserved freshen-up over the summer break. Indeed, every season, the car’s rotor-motor is disassembled and checked regardless of its reliability — such preventative maintenance isn’t too surprising, given this RX-7’s engine is often called upon to rev out to a dizzy 10,500rpm. The car’s gearbox also receives regular and thorough once-overs, given the immense stress on internal components. The only other items usually checked every one or two rallies are the axles; Marcus sees these as a potential weak link due to the power and drive through the wheels.

Marcus’ straightforward take on the matter is that rotaries either go or they don’t, so it’s pretty simple really — and he’s certainly looking forward to many more years campaigning this Group B RX-7, so watch out for him the next time you step out to spectate a round of the NZRC. His classic rotary may not have the absolute speed and precision of a modern four-wheel–drive rally weapon, but the noise the car makes and spectacle of his RX-7 are certainly thrilling for spectators.

As an aside, Marcus’ rotary passion extends to a completely original 1971 Mazda R100 coupé and a 1974 Mazda RX-4 coupé, although he’s currently restoring a 1967 Fiat 500. Can you fit a 13B into a Fiat?

Marcus van Klink’s competition information (Group B RX-7)

- Number of rallies (in this car): 20-plus

Results include:

- Winner, International Classic Rally of Otago 2012

- Historic Champion, NZRC 2012

- Historic Challenge Trophy, Malcolm Stewart Classic Rally 2012\

- Overall champion, Mainland Rally Series; first two-wheel-drive car to win the overall title in several years

- NZRC 2013 Historic class — winners at GoPro Daybreaker Rally and Vantage Aluminium Joinery Possum Bourne Memorial Rally

984 Group B Mazda RX-7

- Engine: Fuel-injected 13B — factory Mazda peripheral port

- Capacity: 1300cc

- Max. power: Approx. 224kW (300bhp)

- Transmission: Modena five-speed dog box

- Suspension: Murray Coutts (MCA)

- Brakes: AP Racing calipers and discs

- Tyres: Dunlop and Kumho 15-inch gravel tyres

- Body: Fibreglass, steel doors and under-body

- Weight: 1200kg — NZRC regulation (minimum)

- Max. speed: 215kph (on gravel!)

- Original build time: Six months

Marcus’ memorable moments

Worst Moment

“I got green-stickered by the police at the World Rally Championship event in 2012 in Auckland while touring to the first stage on day one. We are middle-aged men, had our race overalls on, touring headsets on, et cetera. Sebastien Loeb driving for Citroën got pulled over on the same event for speeding, but got let off! I still maintain that if I was better looking, it may have been a better ending!”

The offending sticker was removed later that day, as the Mazda met all compliance rules — but not before Marcus and Dave had to race through several stages with the thing still stuck to the windscreen.

Best Moment

“Winning the Otago Classic Rally in 2012. It was the first time a Mazda has ever won that rally, so it was a pretty big moment for that car, and us. Otago is renowned for its fast tricky roads. In fact, it nearly caught us out too, but luckily we got away with it and ended up winning! Crossing the finish line and winning that event was just awesome. Nothing has beat that — yet!”

Marcus would like to thank Brent and Deane Buist from Palmside Automotive; Al Marsh Rotorsport; Dave Neill; Wayne Girdler; and, of course, his wife, Jemma, and their two daughters.

This article originally featured in the February 2014 issue of New Zealand Classic Car (Issue No. 278). Don’t miss out on having this mag in your collection. Grab one of the last print copies, or grab a digital copy below: