From 1992 to 2000, the world touring car championship resonated to the sound of screaming naturally aspirated 2.0-litres. With a growing number of these super tourers ending up in New Zealand, we take a look at five of the best

Undoubtedly, many readers look back fondly on the Group A era of touring cars. This was a time of generous advancement in turbo technology and motorsport electronics, and, of course, it gave birth to a segment of performance production cars so treasured by those looking to quench their thirst for speed. But, after the 1992 season, Group A was dead — and the formula that replaced it on a global scale was aptly named Super Touring, but the base cars were anything but super in production form.

In brief, the rules dictated that the base vehicle must be a four-door sedan, with a minimum length of 4.2m. Engines were restricted to 2.0-litre naturally aspirated, with a maximum of six cylinders, and manufacturers were required to produce 25,000 of whichever model they wished to homologate. The creation of homologation specials was, thus, a costly, pointless exercise, and the result was the appearance of cars like the Ford Mondeo, Nissan Primera, Toyota Carina, and Peugeot 405 as series participants.

So read on, as we detail the past and present of some of the coolest historic race hardware found anywhere throughout our land.

Bland, boring, dad-mobiles the cars may have been in stock form, but, when built to Super Touring rules, the vehicles and the racing were anything but. Tarmac-scraping ride heights, slick-shod 18- or 19-inch wheels, and high-strung power plants limited to 8500rpm ensured that the cars provided a visual and aural spectacle. The take-no-prisoners, door-banging, kerb-hopping nature of the racing also proved hugely popular, and a new era of legendary tin-top battles was born.

Decades on, and, popularity of the Historic Touring Cars NZ group of enthusiasts is growing, we’re now lucky enough to be welcoming an influx of these super tourers into New Zealand, which are joining the grid for select summer meetings.

If you’re wondering, the Historic Touring Cars NZ group, founded around 10 years ago by a small group of racers interested in running their valuable Group A cars together, focuses on ‘genuine’ touring cars with race history, spanning the years from around 1972 to the mid to late ’90s. This ensures an eclectic group of cars, although it predominantly attracts Group A and Super Touring cars — the latter growing in popularity as the Group A cars’ purchase price grows ever larger, while the 2.0-litres remain slightly more affordable. Every car is turned out immaculately and raced with vigour, enabling spectators to see and hear an authentic touring car blast-from-the-past.

So read on, as we detail the past and present of some of the coolest historic race hardware found anywhere throughout our land.

1993 BMW 318i (E36)

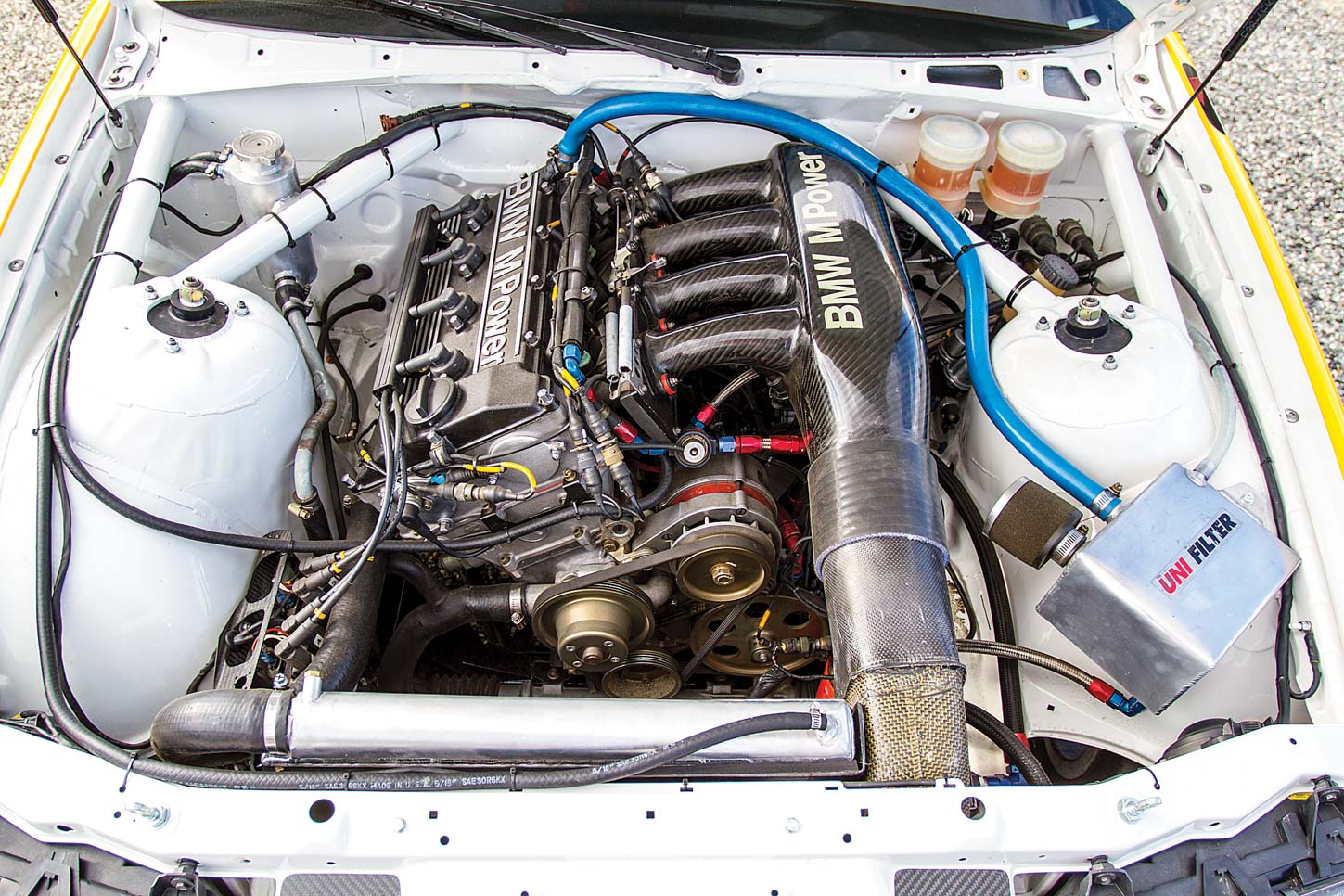

Any story about touring car racing would be empty without including BMW, the manufacturer most indelibly linked with global production-based touring car series. After a dominant period across the world in Group A racing with the iconic boxy silhouette of the E30 M3, the demise of that formula and the dawn of Super Touring saw BMW develop its new contender. While the initial E36s were two door, 1993 saw a regulations-compliant four-door variant of the E36 take to circuits worldwide to pick up where the E30 left off.

Later, BMW Motorsport developed the S42 2.0-litre for the express purpose of competing in Super Touring, but these earlier cars made do with a downsized variant of the S14 2.5-litre. The S14, of course, was the engine that powered several E30 M3s to race victories around the globe. In this smaller-displacement form, and limited to 8500rpm, the 2.0-litre manages 209 screaming kilowatts, assisted by the 13:1 compression ratio. These earlier cars really set the scene for Super Touring development. Snuggled in a typically utilitarian motorsport engine bay, BMW’s four-slide throttles are fed by a carbon-fibre intake plenum producing prodigious intake roar.

As these are a 1993 car, ordinarily, the aero would have appeared far closer to that of a road car. However, creative interpretation of the rules by Alfa Romeo in 1994 meant that aero regulations became more relaxed, and cars sprouted updated splitters and spoilers by 1995. This Benson and Hedges (B&H) car wears the updated aero, which only enhances the slammed ride height and 18-inch Speedline centre-lock wheels. Other period inclusions to these cars are the Holinger six-speed sequential and the Pi Research dash display and data-acquisition unit located in a factory dash shell.

Starting life in 1993 running in Italy, this BMW 318i found its way over to Australia in the care of Tony Longhurst’s stable for the 1994 championship. It was plastered in Longhurst’s distinctive B&H livery, and he went on to take out the series for that year — inclusive of an infamous trackside punch-up with Paul Morris following a spot of paint swapping that put both drivers into the wall at Winton. Subsequently, the car spent several years with varied ASTCC privateers, before being imported into New Zealand in 2003 by Lindsay O’Donnell, who initially campaigned it in South Island endurance races. With the surge in Historic Touring Car interest, the BMW has now been completely restored to 1994 specification.

1996 Nissan Primera (P10)

As super Touring dawned, so did a new, concerted effort by Nissan to seize a European touring car crown

Nissan’s involvement in Group A touring car racing wasn’t quite as prominent in Europe as it was throughout Japan, Australia, and New Zealand. For Group A, Nissan developed the DR30 Skyline; the HR31 GTS-R Skyline, powered by the RB20DET; and the unforgettable ‘Godzilla’ — the mighty R32 GT-R. Each of these cars saw increased success in the championships it contested, but, as the age of Super Touring dawned, so did a new, concerted effort by Nissan to seize a European touring car crown.

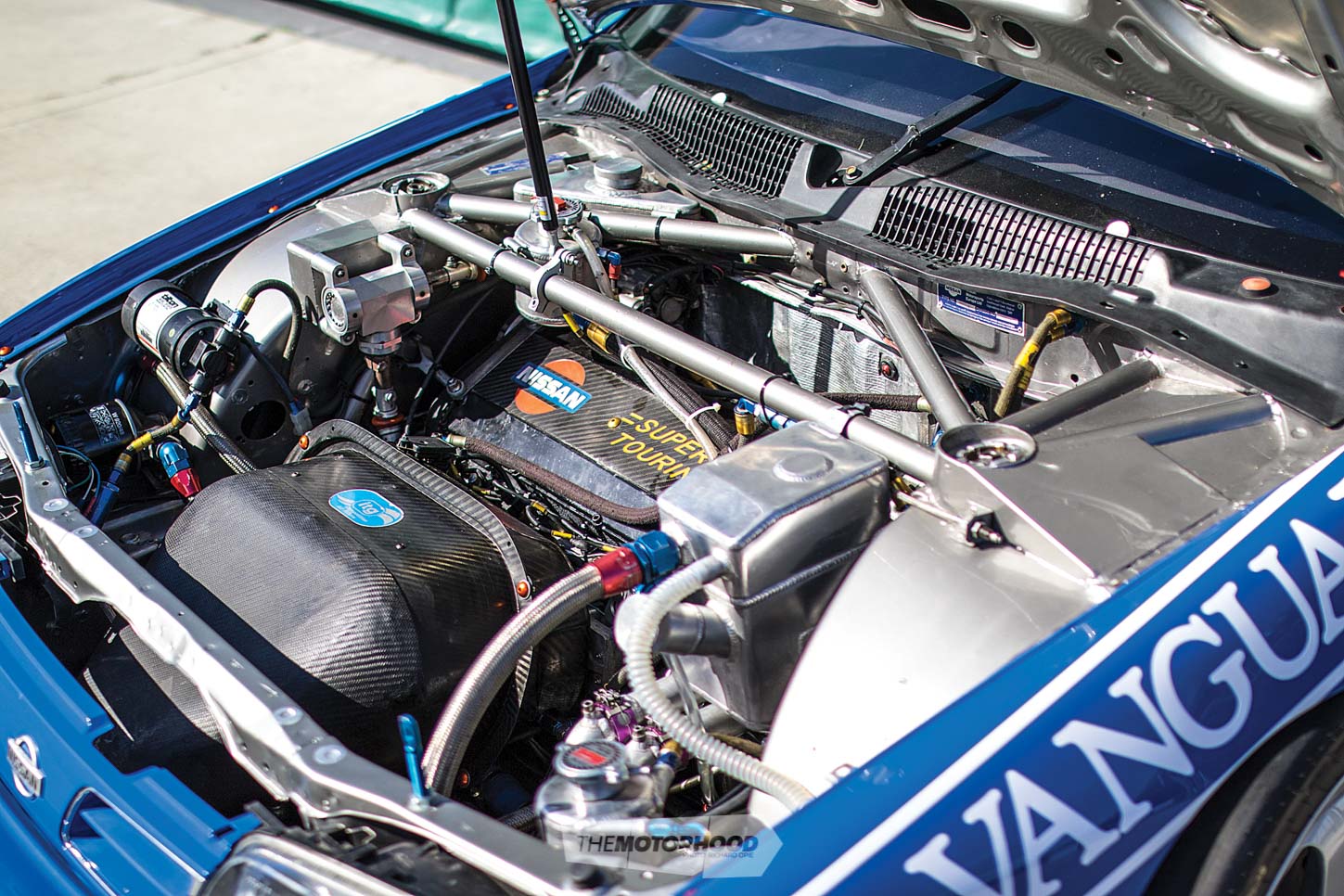

Nissan turned up at the beginning with its boxy P10 Primera — perhaps at face value one of the least-inspiring bland-mobiles on which to base a prospective race winner. Race car engineering and development specialist Janspeed took on the job of converting the P10 into a capable Super Touring car with factory support. This continued until 1995, when Janspeed withdrew its British Touring Car Championship (BTCC) operation, which prompted a temporary hiatus from the series by Nissan. Nissan had meanwhile established its own Nissan Motorsport Europe (NME) operation, eventually taking over the Super Touring program.

While the P11 Primera may have been in its sights by this stage, this 1996 P10 (chassis No. 23) left the NME workshop as one of the ultimate evolutions of the P10 bodyshell. Destined for the Spanish Touring Car Championship, the car was driven in ’96 by ex–Formula 1 (F1) pilot Eric van de Poele, managing a fifth-overall placing with a couple of race wins. The following year, the car competed in the Central European championship with Czech Vaclav Bervid, earning second overall and several race wins, pole positions, and fastest laps.

In contrast to the earlier BMW, this P10 is notably more advanced. The SR20-based 2.0-litre is set low and back in the engine bay, with a reversed head and eight injectors contributing to its 224-kilowatt output. A six-speed Hewland gearbox handles gear ratios, and engine management remains under control of a period Pectel T6 2000 with an Aim dash. One notable feature of the Primera is the dual-caliper front-brake set-up — huge two-piece rotors are clamped by twin water-cooled AP calipers at either end. To complement the Nissan’s country of origin, the wheels are also Japanese — finely crafted 19-inch Rays Engineering ‘fortesst’ centre locks. Cabin-adjustable anti-roll bars, as well as swathes of carbon fibre, adorn the interior, with a floor-mounted pedal box, extended steering column, and set-back seat.

Restored to its original ’96 CET Repsol livery in 2015 by UK Nissan Super Touring specialists Dave Jarman and Keith Butcher, the Primera is a recent arrival to New Zealand shores with owner Murray Sinclair, for the purpose of historic competition.

1997 Volvo S40

he S40s proved a potent package for their debut season

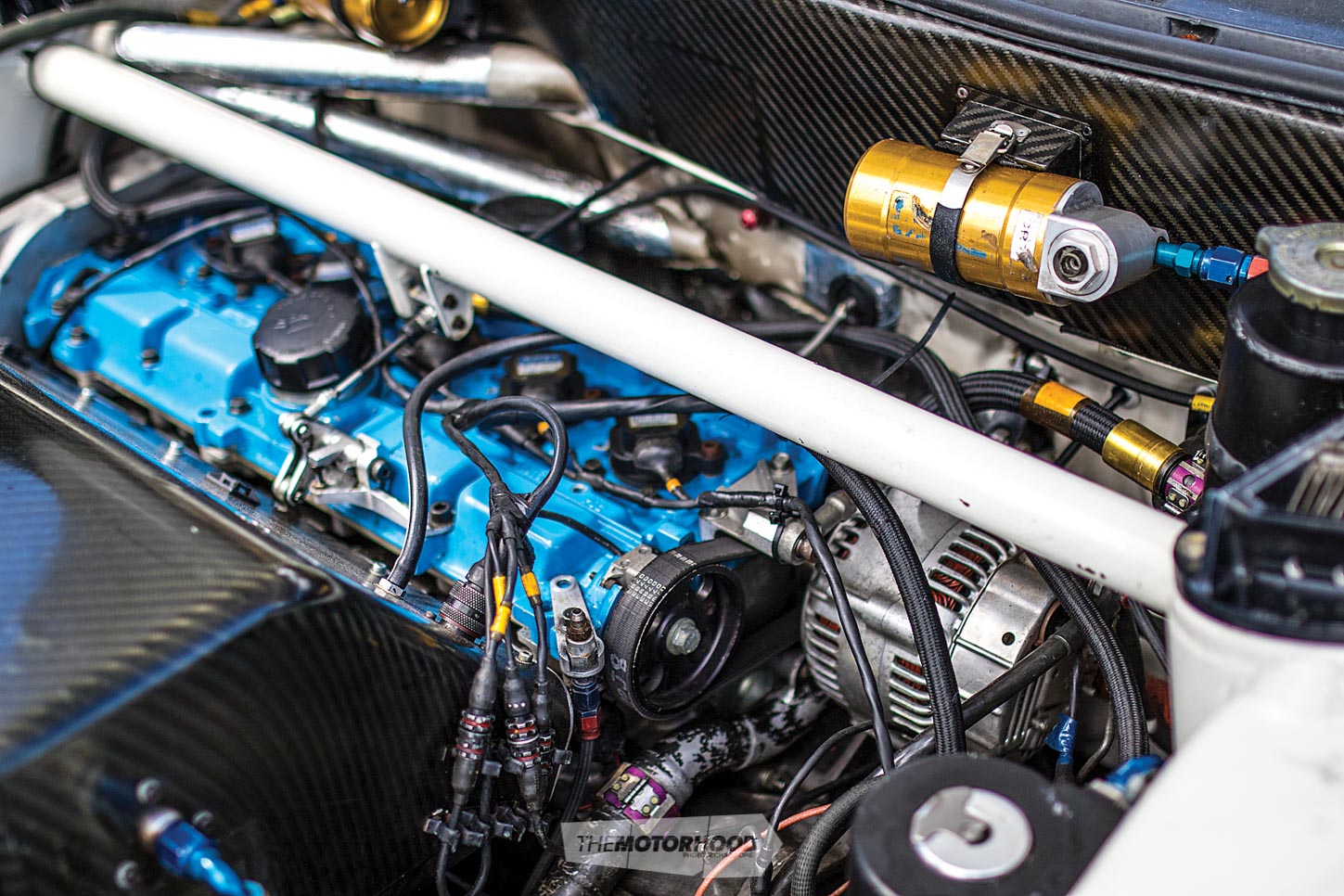

Mention ‘Volvo BTCC car’, and, nine times out of 10, people will immediately respond with, ‘Oh yeah, the wagon!’ In 1994, Volvo burst onto the Super Touring scene with the unlikely 850 ‘estate’ (to use the correct UK terminology) prepared by the experienced Tom Walkinshaw Racing (TWR) team and packing a barking 2.0-litre five-cylinder. Switching to an 850 sedan for ’95 and ’96, Volvo attacked the ’97 BTCC with an all-new car using the 850’s showroom replacement, the uncharacteristically swoopy S40.

While the bodywork was fresh, mechanically, these S40s were otherwise an evolution of the 850, and retained the howling five-cylinder engine. Unique to the 1997 S40, the engine rotation was reversed to run anticlockwise, something TWR engineers theorized would assist traction. Unlike most other front-wheel-drive (FWD) super tourers, the cylinder head wasn’t reversed; rather, the entire engine was. Pumping out circa 224kW at the mandated 8500 rev limit through an Xtrac six-speed sequential box, the S40s proved a potent package for their debut season, with both cars finishing in the top 10 by the season’s end.

Retaining that signature Super Touring aesthetic, the S40s sat close to the deck on Ohlins remote-reservoir suspension and bespoke uprights. The 19-inch BBS centre locks sank into stock-appearing arches covering giant brake rotors, and, while some contestants in the series employed dual-caliper front arrangements, Volvo elected to use eight-pot front and four-pot rear calipers. Kerb weight? A mere 975kg!

Now owned by Lindsay O’Donnell, this particular car started life in the ’97 BTCC. It’s stamped with chassis tags with the number R7-004. Briton Kelvin Burt occupied the driver’s Recaro for the ’97 season, bringing the car home 10th in the standings after finishing as high as fourth on a couple of occasions. For 1998, the car was sent to Australia with ex-pat Kiwi tin-top specialist Jim Richards in the hot seat for the local Volvo team to battle its BMW and Audi rivals.

Despite taking race wins at Phillip Island and Eastern Creek, Richards’ FWD Volvo was unable to conquer the barnstorming all-wheel-drive (AWD) Audis (by then outlawed in Europe), and he finished third in the championship behind the pair of Quattros.

Recently recommissioned in the UK by touring car engineer Jonny Westbrook, the S40 proved a pacesetter at the 2016 Brands Hatch Super Prix, snagging pole in the Historic Touring Car class by a full second, before being swept across to New Zealand shores, where the car will be campaigned among the Historic Touring Car collective.

1998 Nissan Primera (P11)

Expect to see Phil chopping through the gears at 8000rpm at selected Historic Touring car meetings

The BTCC Super Touring era wasn’t limited to huge-budget factory competitors. As well as the top manufacturer-based teams battling it out for the podium, there was a separate cup reserved for independent teams. These, more often than not, relied on machinery that was a season or two old, and while the hardware may not have been top tier, the racing among the independents was equally cut-and-thrust. The quicker competitors among the independents could often be found vying for minor places with the less competitive of the factory efforts.

Easily the most prominent of the independent drivers was Matt Neal, who spent the Super Touring years largely driving for his father’s Team Dynamics outfit, first in BMWs, then Mondeos, and ultimately finishing up at the wheel of a P11 Nissan Primera. One of those Primeras is now here in New Zealand, in the custody of Canterbury’s Phil Mauger. The Team Dynamics P11 is very closely based on the last of the NME-built P10 cars, such as the Spanish Primera detailed earlier, and, in the metal, the similarities are obvious. Taking one of the ’97-spec factory cars, the Team Dynamics guys secured the latest-spec shell from NME and set about integrating the mechanicals to the bodyshell for the 1998 season.

Built around its extensive roll cage on a jig, the Primera uses all steel panels, as per the regs. Front and rear aero reflect the development invested in this aspect of super tourers at the time, particularly in the aggressive front-splitter arrangement seemingly hanging from a factory-issue Primera front-bumper upper. Radiused front guards house the same 19-inch Rays as the ’96 P10, with an equivalent water-cooled AP twin-caliper front arrangement. Koni shocks and fabricated suspension components at each corner complete the chassis. Interestingly, a stock FWD Primera used a rear beam axle; these cars use the independent-rear-suspension (IRS) arrangement found in the 4WD model P11.

Peering into the engine bay of the Team Dynamics car reveals an arrangement akin to that in the P10, with the same low-mounted set-back engine with reversed head, eight injectors, Pectel engine management, and, again, around 224kW. The gearbox is an Xtrac sequential unit, with fully interchangeable ratios allowing gearing to be tailored to the track along with the diff — a trick combination of plate and viscous-type LSD.

This is the second time this car has been brought to New Zealand — its first visit to our shores was at the hands of Historic Touring Car stalwart Rick Michels, before it was spirited back to its home country in 2008 to run the following year at Silverstone. Now that it’s returned to New Zealand, expect to see Phil chopping through the gears at 8000rpm at selected Historic Touring Car meetings.

2000 Ford Mondeo V6

Towards the tail end of the 1990s, it was becoming evident that the Super Touring formula was nearing the end of its tenure. Factors that had killed off the Group A period were rearing their head in a similar fashion — namely, soaring development and running costs all racked up in the quest to seize the BTCC crown, killing off all but the dedicated teams. The Mondeo had contested the BTCC since part way through the 1993 season, with Kiwi Paul Radisich making an immediate impact on the championship. Distinctive due to the ear-piercing scream emitted by its Mazda-derived 2.0-litre Cosworth V6, Radisich took the Mondeo to third-place finishes in both ’93 and ’94, which, until the 2000, remained the best results for Ford’s BTCC efforts.

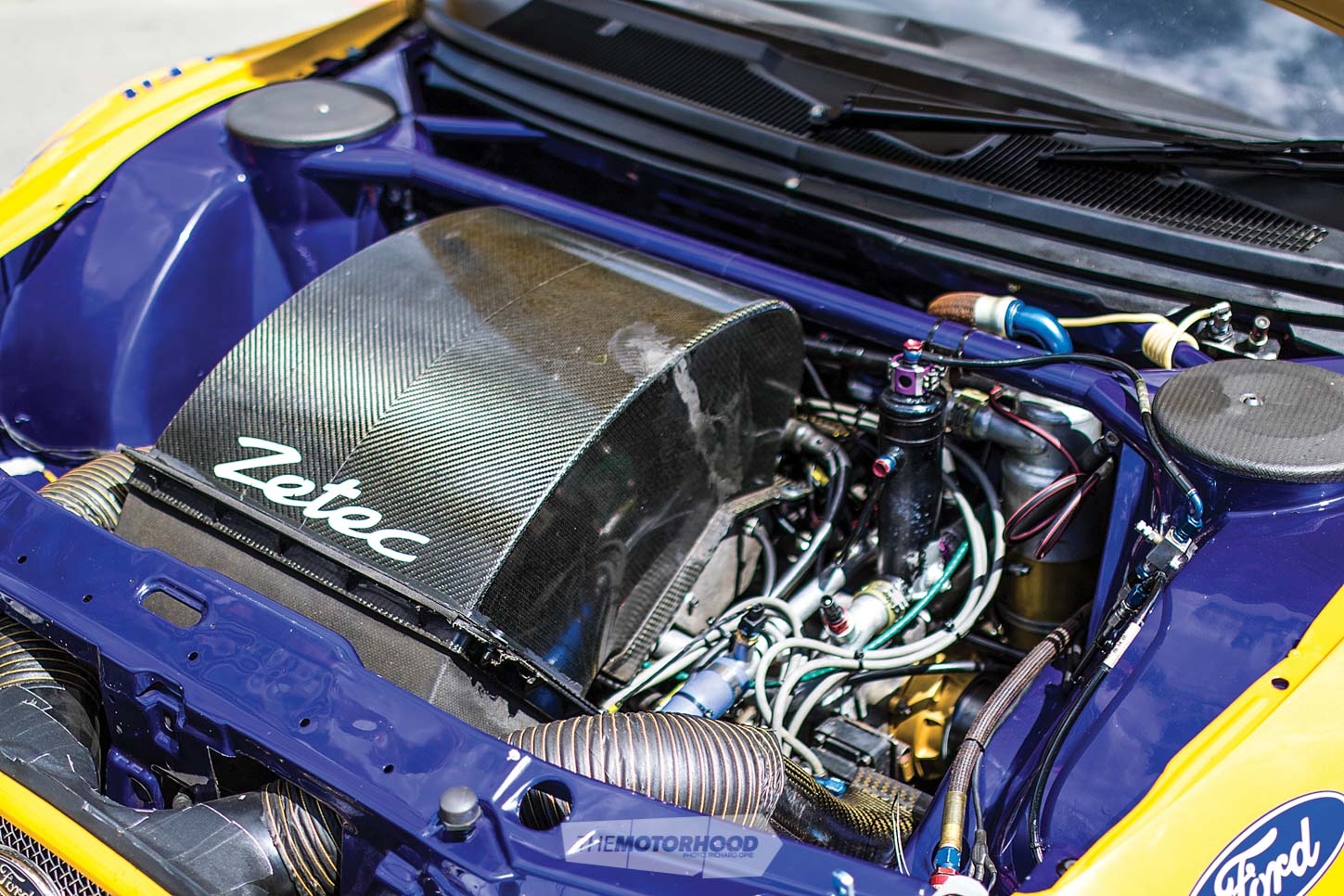

Prodrive took the reins of Ford’s campaign for outright victory in 1999, and set about a radical reimagining of the Mondeo platform, a process that even today leaves Super Touring geeks discussing the sheer expense involved in creating the most technically advanced Super Touring car of the era. A reputed £12M was spent on the overall campaign for the 2000 championship, with each of the three factory Mondeos costing £1M apiece.

Gazing over the form of Scott O’Donnell’s ex–Rickard Rydell, Prodrive-built Mondeo V6 after checking out some of the earlier cars, it’s evident where the money has gone. Peering inside the Mondeo, you’ll see it boasts an elaborate roll cage that ties into the rear suspension–mount points, but it’s the dash and driving position that stand out. The dash, while loosely resembling that of a production car, is awash with carbon fibre, with carbon also employed in the construction of the switch/fuse box mounted centrally and, interestingly, the floor-mount pedal box. The driver’s seat is shifted towards the centre line of the vehicle, with the seat back located aft of the B-pillar.

Under the bonnet, Prodrive re-engineered the 224-plus-kilowatt V6 to the point that it no longer resembles a production engine — not that it’s visible at a glance beneath the huge carbon-fibre intake duct. A carbon-Kevlar cam covers the V6, barely discernible as it sits so low and far back that the driveshafts from the Xtrac 306 sequential gearbox actually run through the centre of the ‘V’.

Macpherson struts with shocks by Koni handle all four corners, tied to the chassis by bespoke suspension arms kitted with F1-spec spherical bearings. Peeking under the car (difficult because it’s so low) reveals a flat floor. The sheet metal is all steel, as per the regulations, with the front guards enlarged and rolled to accommodate the massive OZ wheels and slicks.

It’d be easy to continue — the detail of the Mondeo is such that it could fill an entire story. Running it is equally detailed — the car’s complex start-up procedure requires the preheating of fluids prior to running, but, nonetheless, Scott and his lads are dedicated to letting us see it run on Kiwi circuits among the Historic grids.

This article originally appeared in NZ Performance Car issue No. 242. Grab yourself a print copy or digital copy at the links below: