We take a walk back into Toyota’s history, to a time before it became the automotive giant we know today

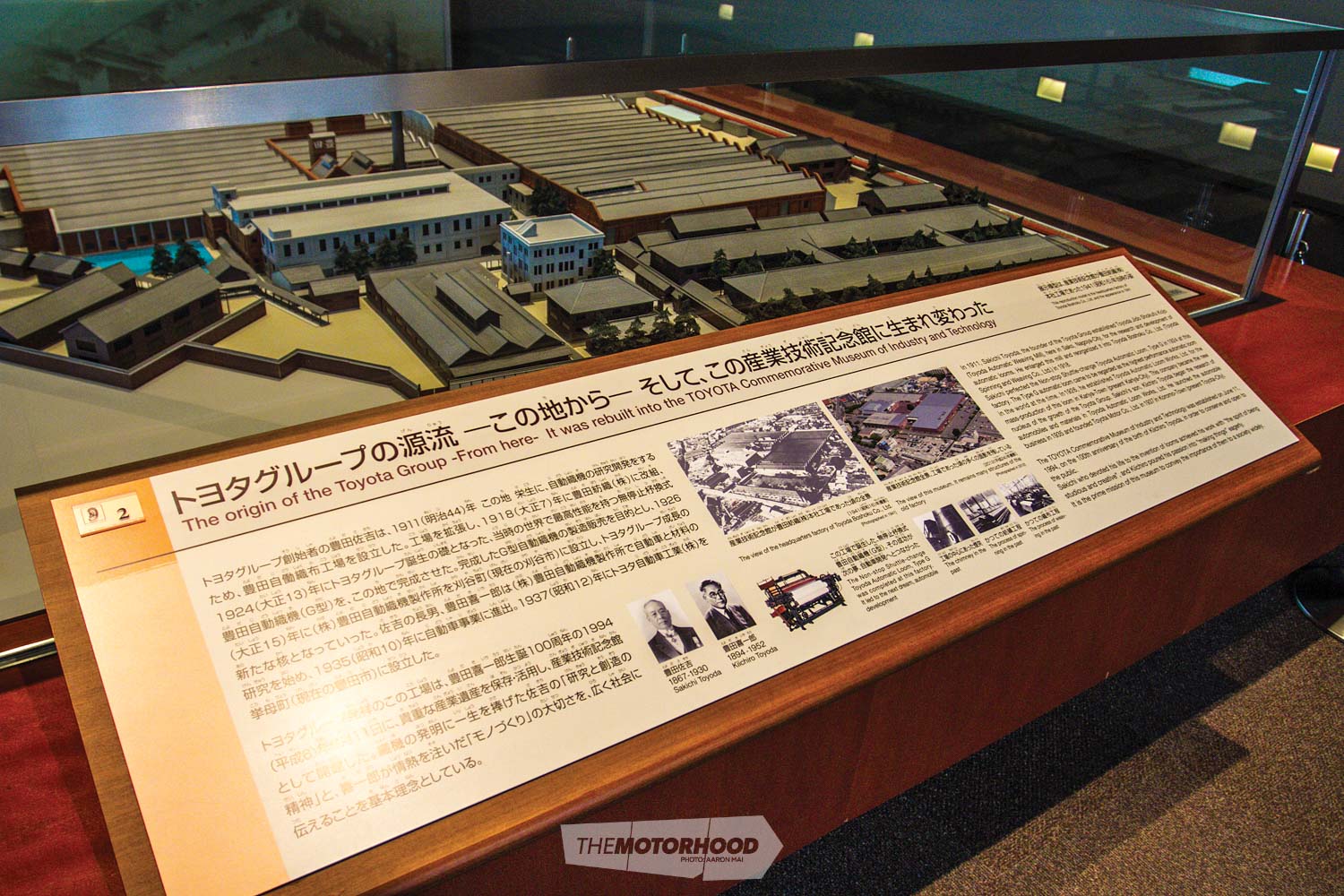

It isn’t the strongest species that survives; it is the one that is most adaptable to change, and Sakichi Toyoda and his son, Kiichiro Toyoda, were exactly that. The founders of our beloved Toyota marque didn’t always dabble in the auto industry — this story is one of adaptability, and goes something along the lines of ‘from cotton to cars’. It’s a fascinating tale, so, when the chance to visit the very first Toyota premises came up while I was visiting Nagoya, I grabbed the opportunity with both hands and set off to see how the Toyoda family created one of the most famous automotive marques in the world.

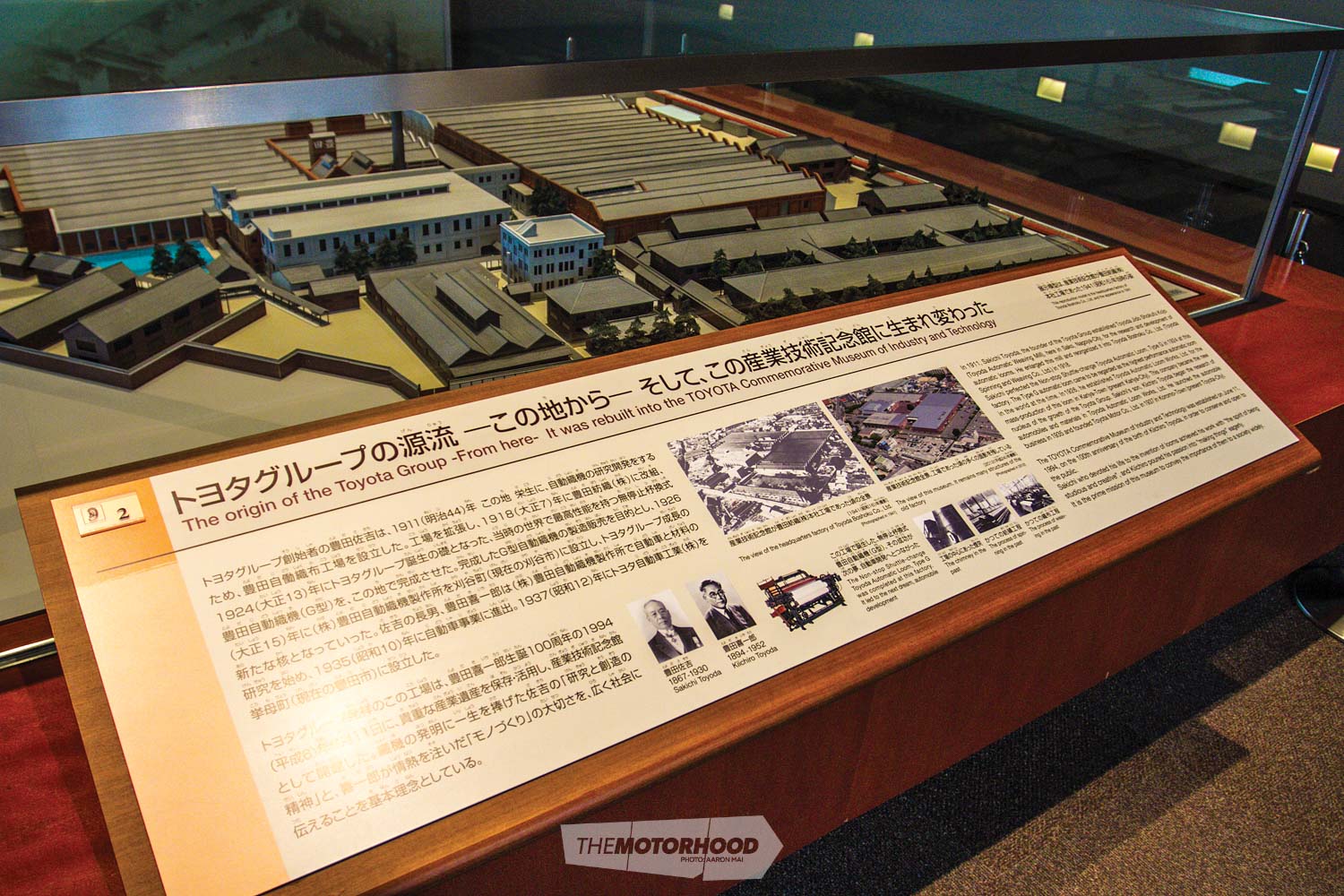

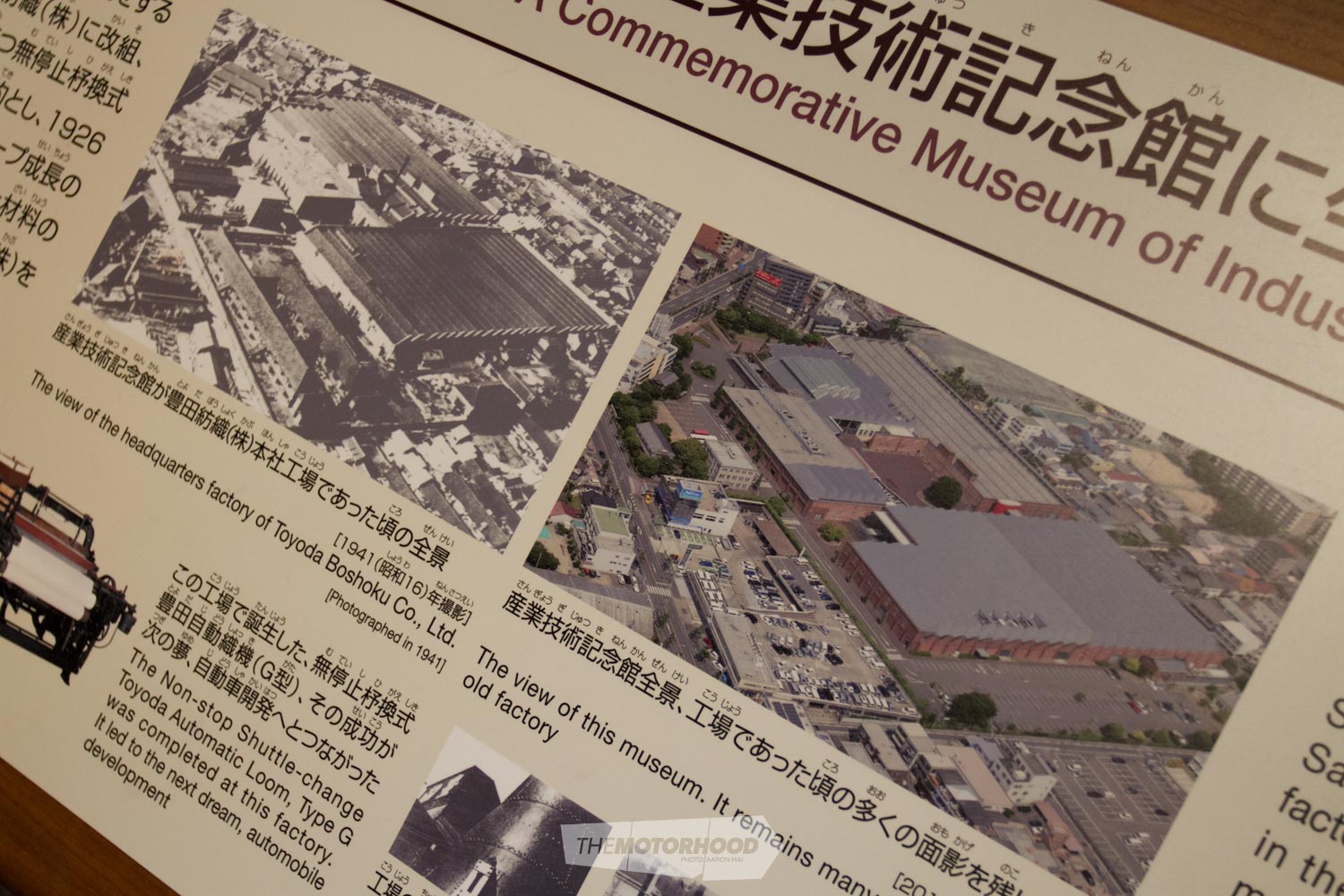

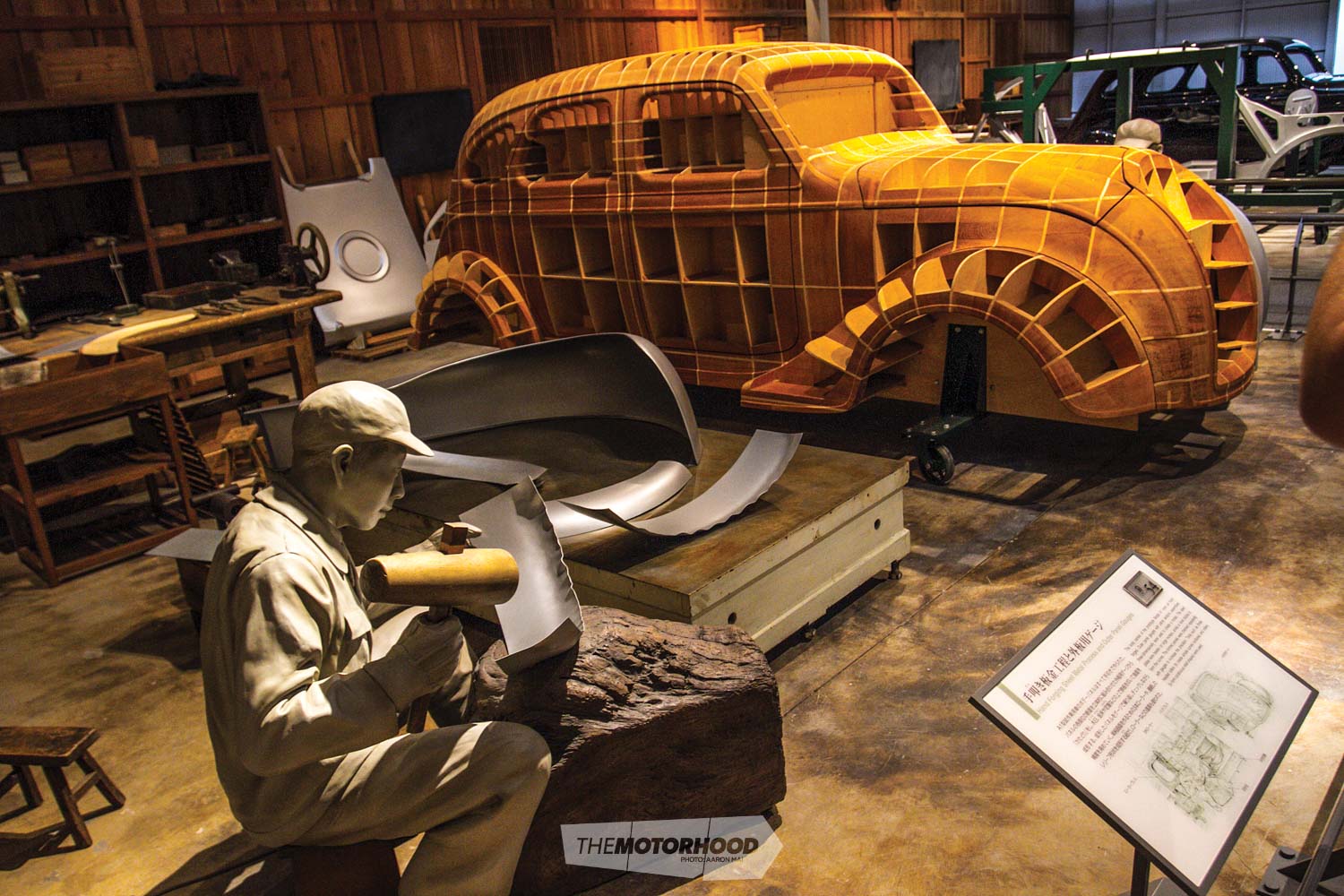

The Toyoda Power Loom was released in 1905 and quickly gained public attention for producing quality cotton fabric. By 1925, the business was a major player in the loom industry, with full automation capability, and the Toyoda Automatic Loom Works, Ltd was formed in 1926. In 1929, the patent to the looms was sold to a British company, generating the capital for Kiichiro Toyoda to begin automobile development. After taking apart a 1933 Chevrolet, he blueprinted the car for a prototype engine he had been working on and used the disassembled Chevrolet car parts to test for strength and rigidity. From this research and development was born the Toyota model AA, which sold for a unit price of ¥3350, or $45 dollars. The name also underwent a change, from ‘Toyoda’ to ‘Toyota’, as it was easier to pronounce, and to write it in the katakana script took eight strokes, a number considered lucky by the Japanese. The Toyota Motor Company Ltd launched in 1937.

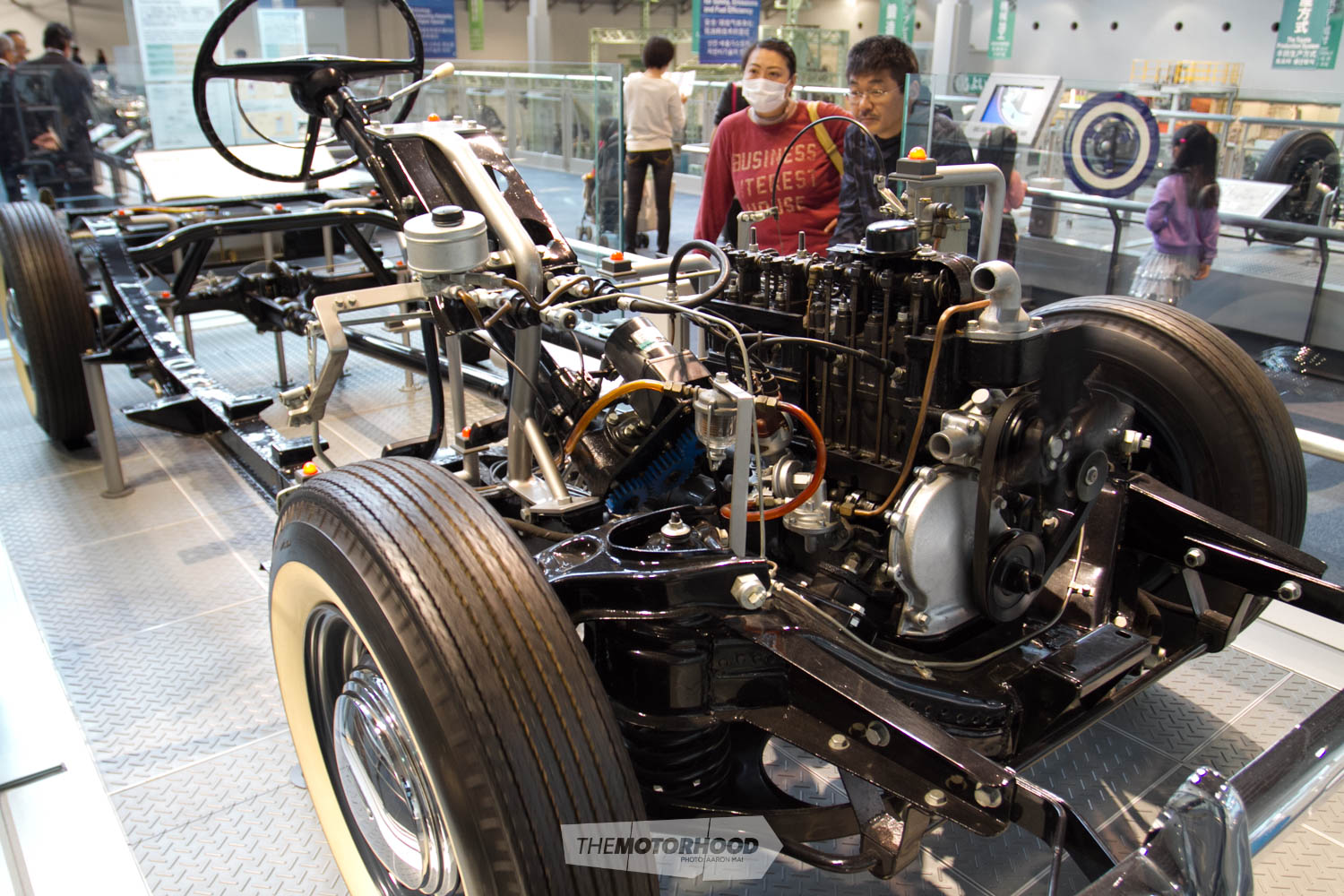

When I visited the original premises and stood on the original production line, it gave me an eerie feeling: as I looked down the building, the wooden skeleton produced perfect ‘tunnels’ for industrial production lines. You could almost feel the ghosts of the first employees running around crafting looms and, later, the first automobile prototypes. Nowadays, it is a museum showcasing the entire history of Toyota with original, working machines spread throughout the complex. Of course, I was more interested in the automotive side of things, so I skipped on into the next room. Walking through the door, we transitioned from fabric to internal combustion, and greeting me was a restored example of an original AA chassis. Though I’m more of a sports car fanatic, I felt privileged to see the beginnings of the Toyota we all know and love today. I guess you could say that this car paved the way for icons such as the Hachi-Roku, Celica, and Supra.

Many of the classic cars are some of the first to have ever rolled off the production lines and would easily be the most immaculate original examples in existence

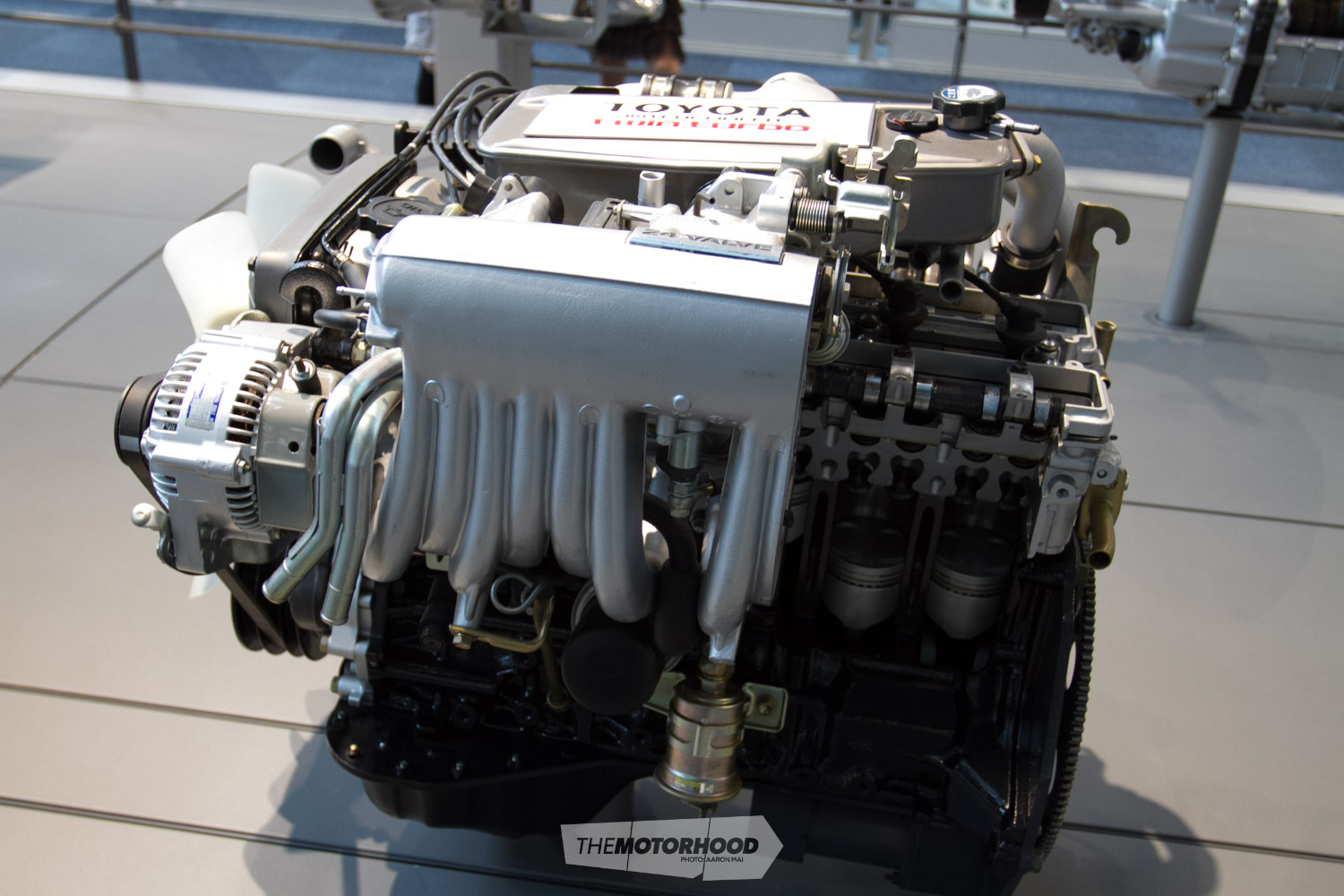

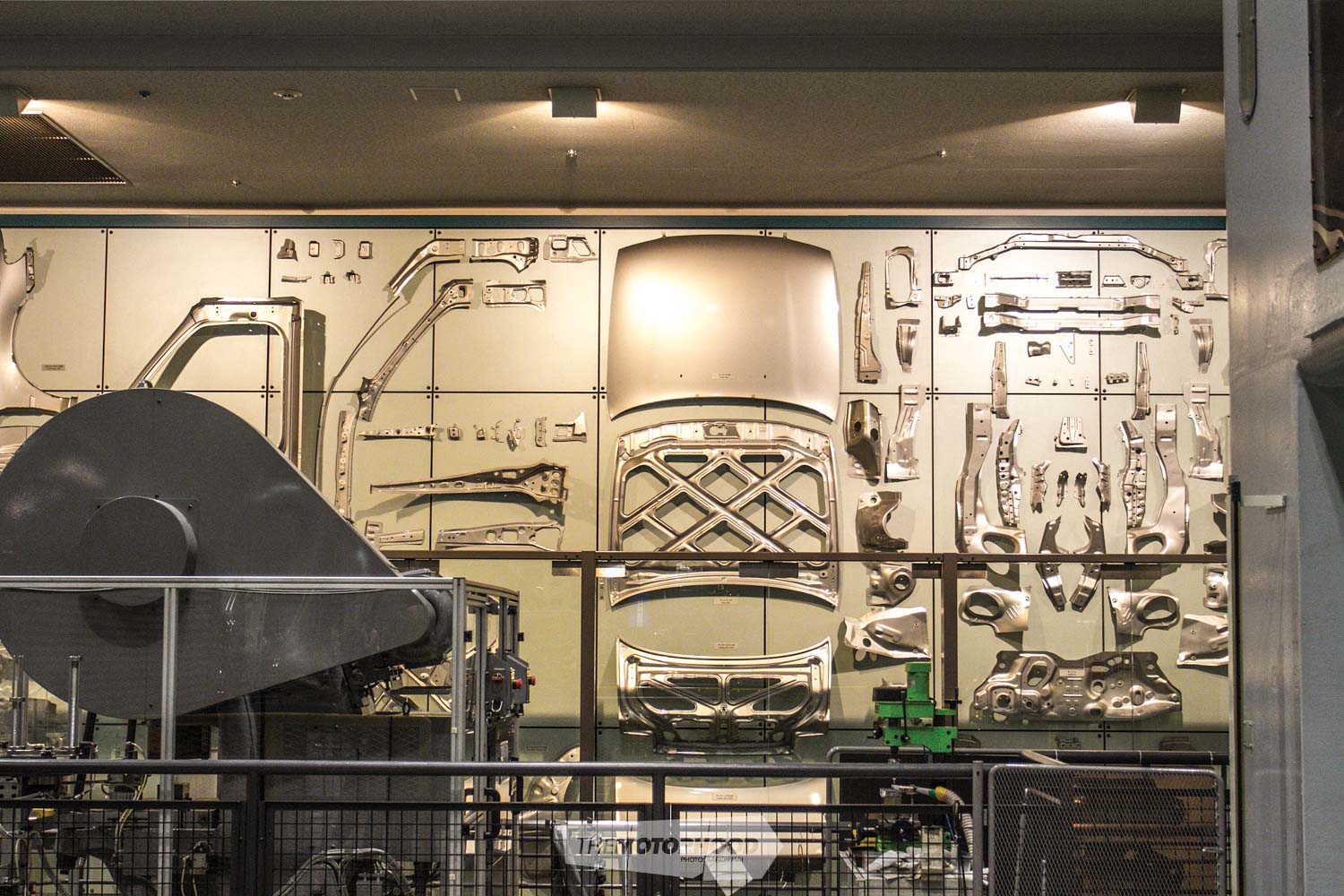

The museum has been set up to showcase pristine examples of some of the best cars in Toyota’s arsenal. Everything from original baremetal chassis to an impressive engine line-up, and even metal presses that create engine internals are on display. Watching a 120-tonne forge press making miniature connecting rods was impressive, until we were told that the full-size ones are done with a 2000-tonne press.

If you’re a Toyota fanatic, this is one experience you wouldn’t want to miss out on. Many of the classic cars are some of the first to have ever rolled off the production lines and would easily be the most immaculate original examples in existence, since Toyota has time-capsuled them.

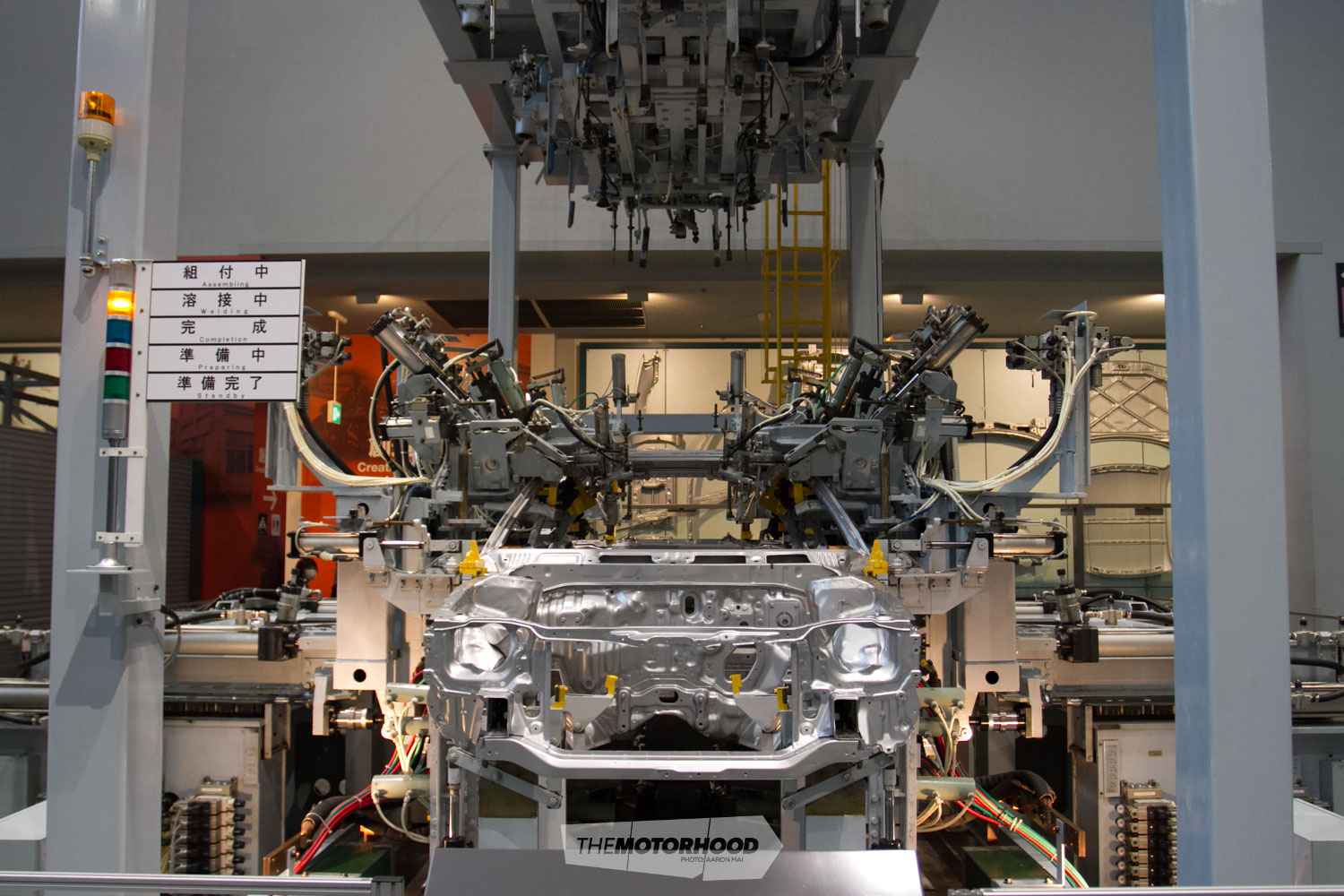

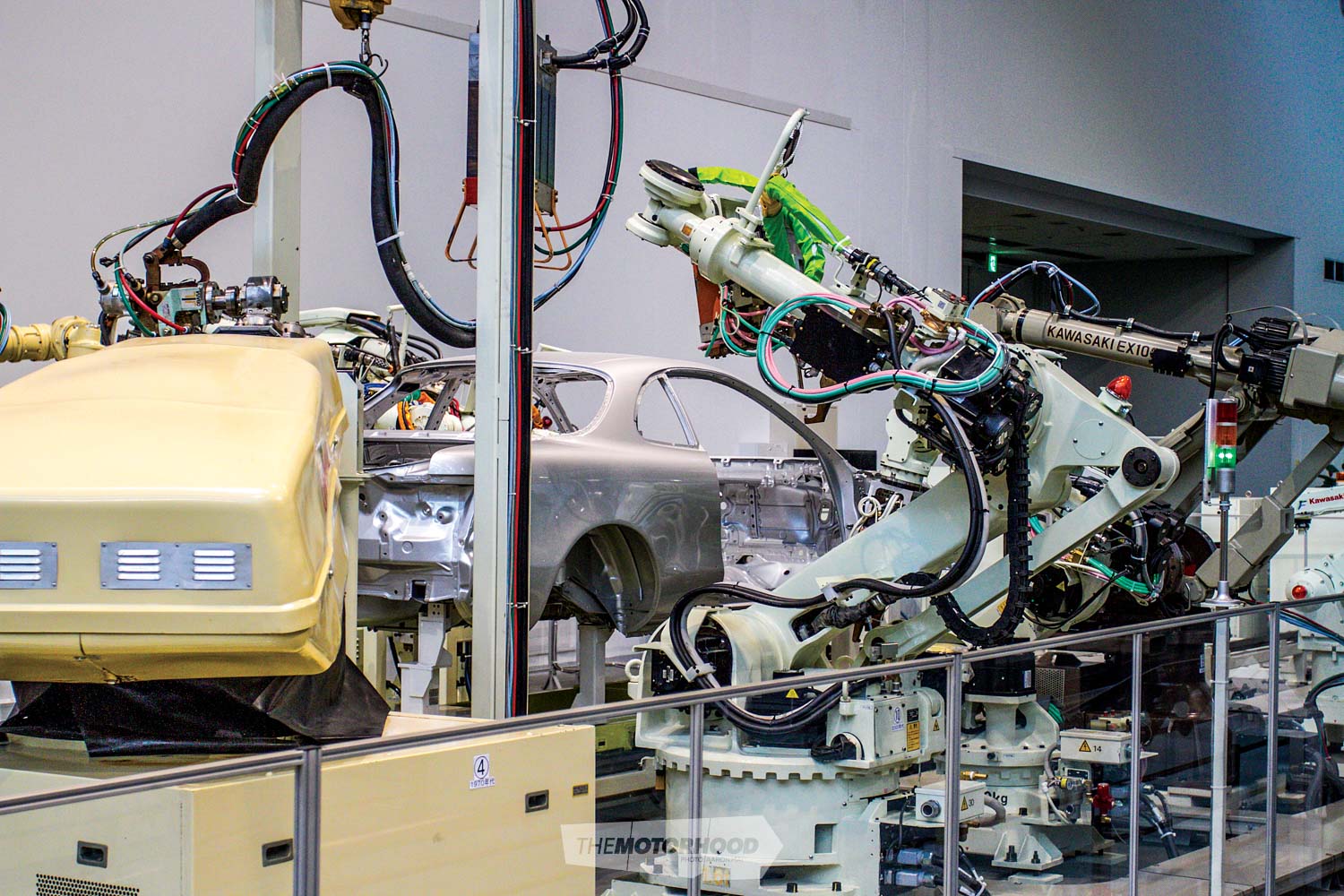

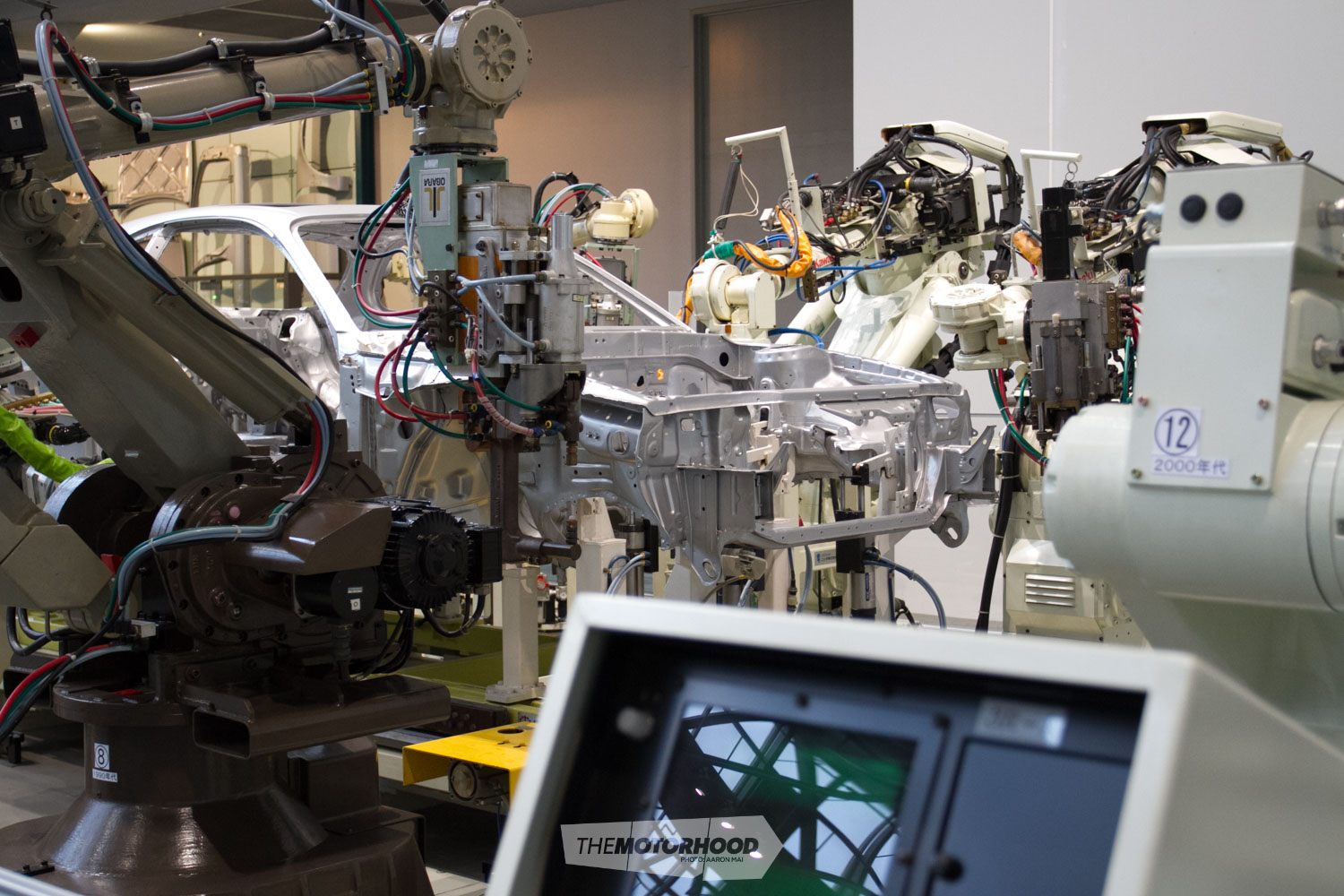

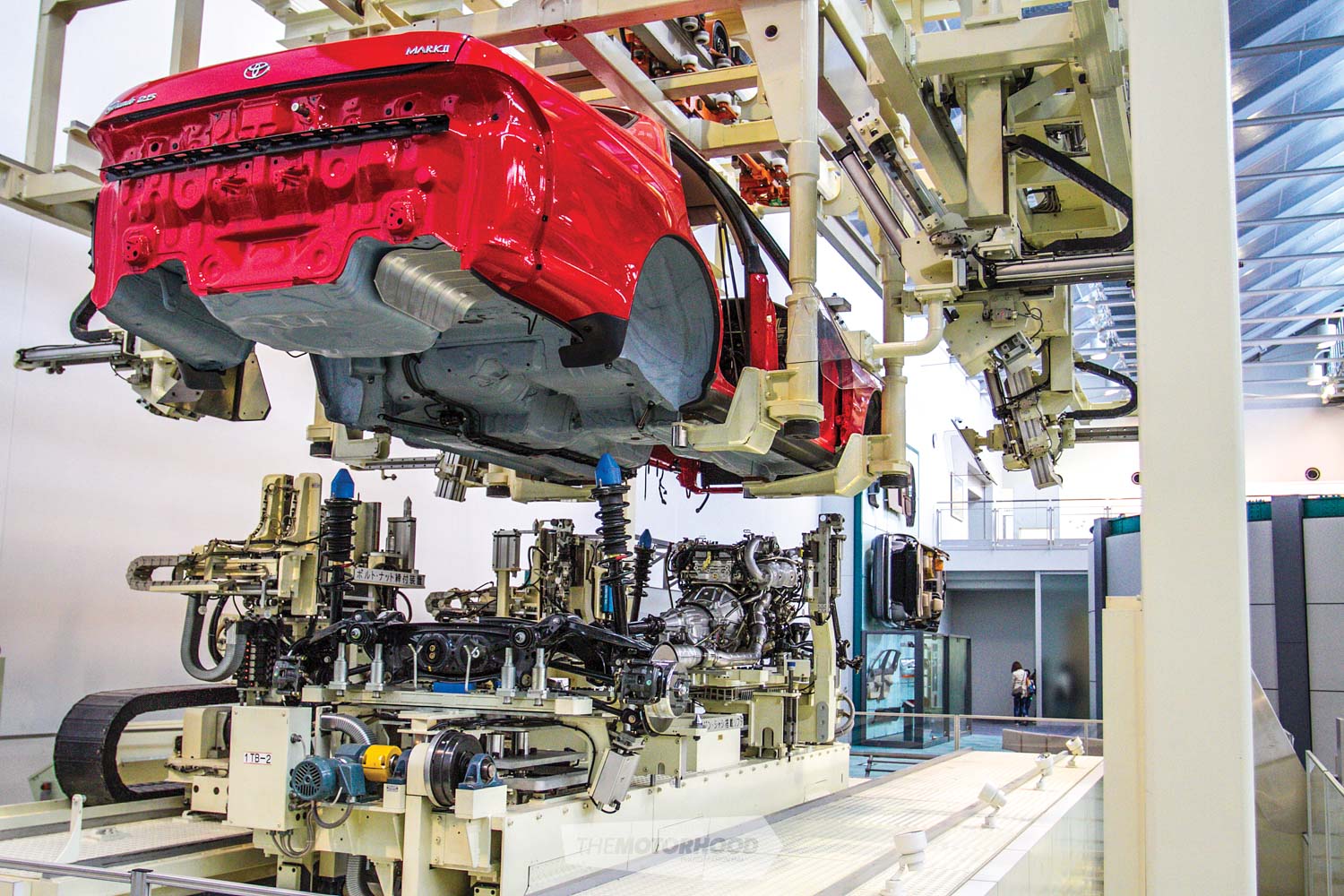

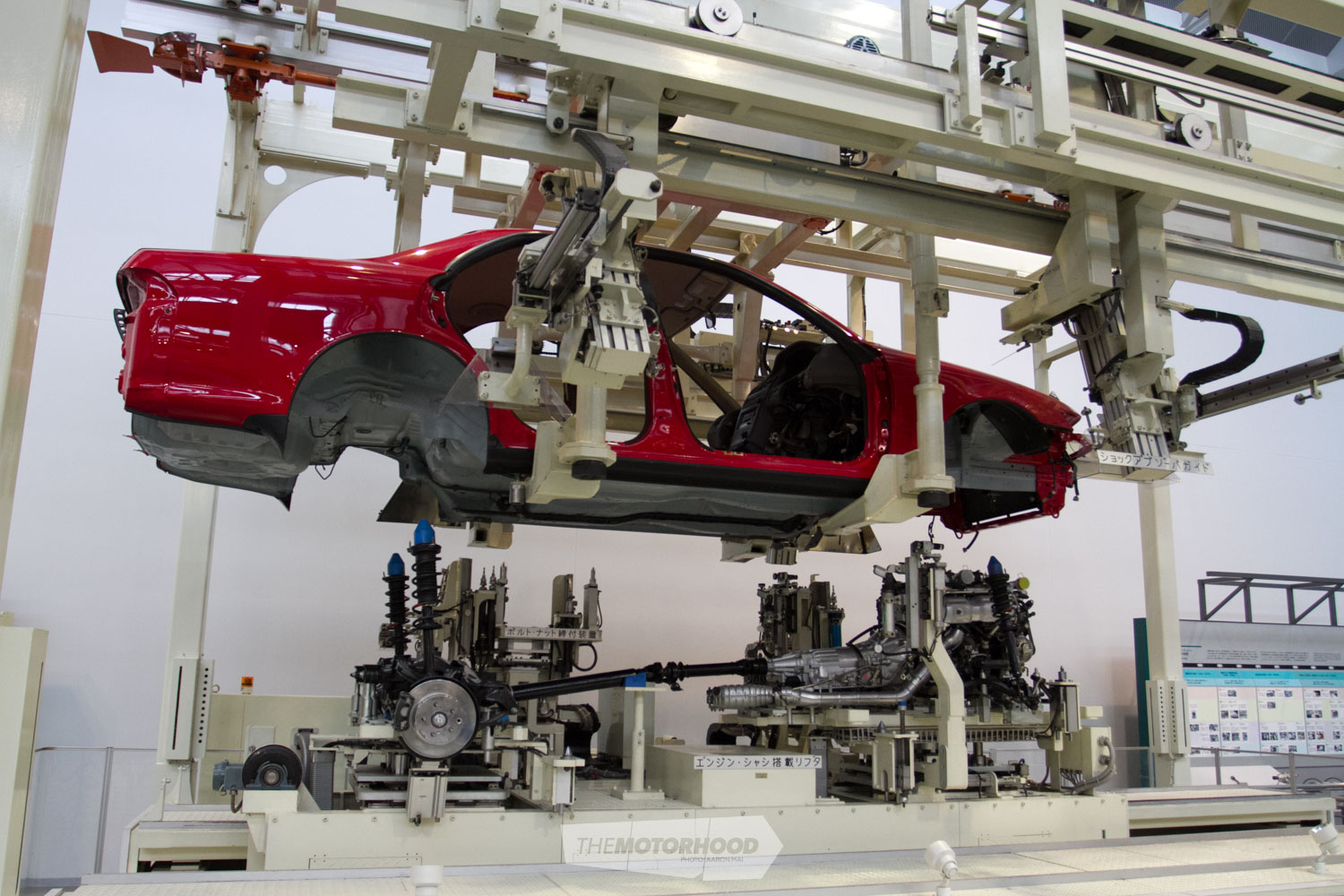

But perhaps the most impressive thing of all was getting an insight into the industrial production lines used by Toyota today. Watching a chassis go from multiple panels to a finished, welded product in mere minutes, then through the automated paint process, finally to be mated up with its engine and drivetrain was a mind-boggling experience. Seeing this makes you realize just how a single Toyota production facility is capable of producing 463 vehicles per day. At the end of the production line was a small image of Kiichiro Toyoda, with the simple phrase, “Before you say you can’t do something — try it.”

This family came from poor, humble beginnings and created the world’s largest automobile manufacturer, a true rags-to-riches story. Visiting Toyota and standing beneath the roof that Toyota’s full-scale manufacture began under is a must-do for any true Toyota fan.