If you scroll back through the history books of drag racing in New Zealand, a number of names stand out — names such as Pete Lodge, Nick Liefting, Garth Hogan, Ivan Jujnovich, and Errol Uttinger, to mention but a few. However, in among the records of New Zealand’s grandfathers of speed, you may also find the name of Mike Gearing.

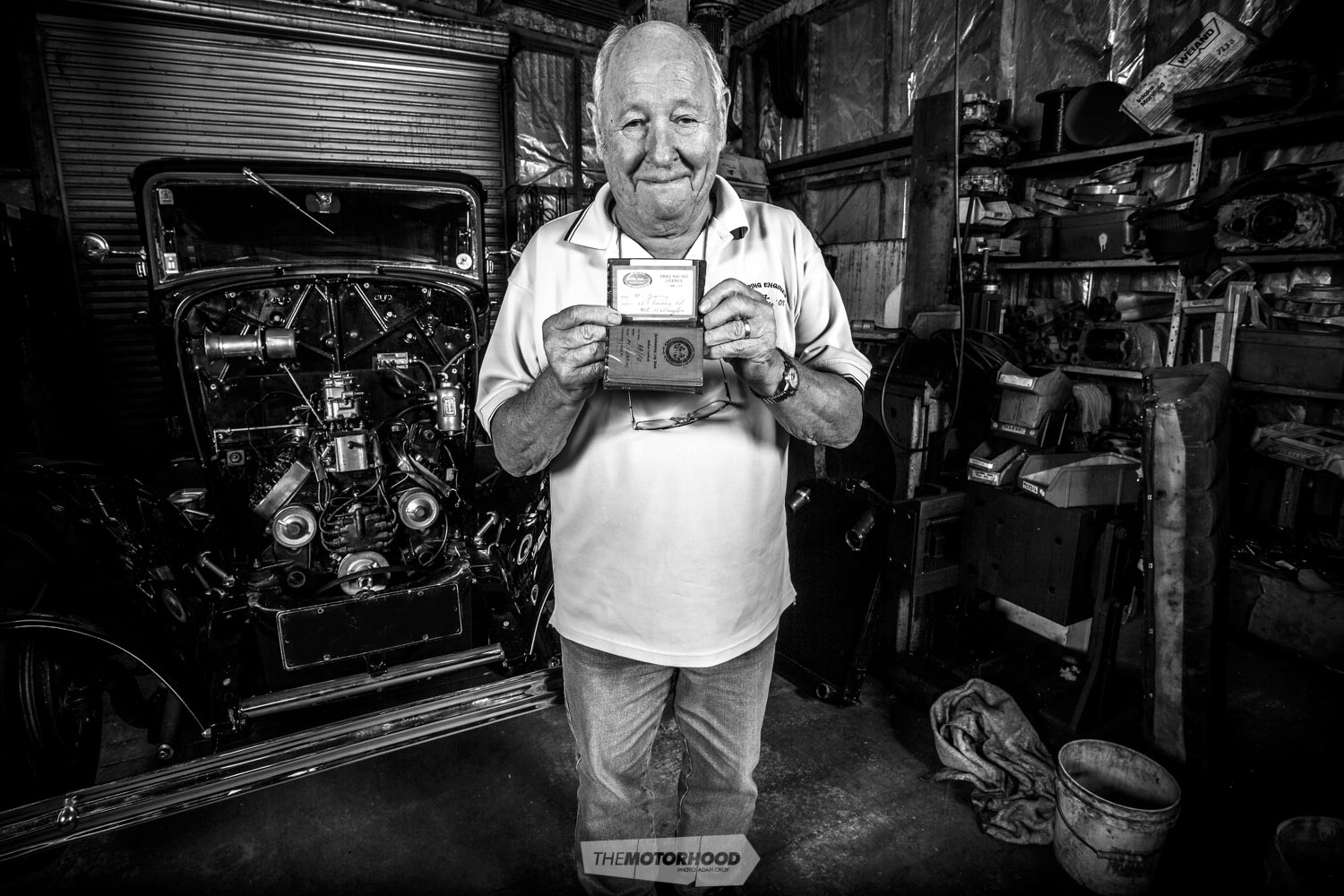

Although his name may not garner the instant recognition of legends such as Garth Hogan and Pete Lodge, Mike Gearing is a bona fide legend of New Zealand drag racing and hot rodding. Born in 1939, before World War II and in a world vastly different from the one we inhabit today, Mike achieved what others could only dream of: operating on a shoestring budget and an inventory of predominantly self-made parts, yet achieving six-second passes at more than 200mph down the quarter-mile in an era when such accomplishments were exclusive to the highest reaches of drag racing, at the same time earning a well-deserved reputation as one of New Zealand’s best engine builders.

Despite his achievements and incredible self-taught knowledge, Gearing is as humble as they come. When he talks about what he has done, he is matter of fact, with no bravado or ego. We were fortunate enough to be able to talk with him about his life and accomplishments, and what follows here is some of what he had to say.

NZV8: Thank you for your time, Mike. The best way to start this interview is probably by asking: who is Mike Gearing, and what got him into what he does to this day?

Mike Gearing (MG): Well, cars were a means of transport, basically. I arrived in this country in 1956, and bought my first car in 1957, or something. I couldn’t drive — I had to get someone to drive the car home. My father was working down country, and he would come home at the weekends, so I had to wait for each weekend to get a lesson.

It was a 1938 Standard Eight. New Zealand in 1956 was quite primitive. It was a different time — rugby, racing, and beer … short hair — I had long hair, tight jeans, and a leather jacket, and I got into all kinds of strife. I stood out.

Where was it you came from before settling in New Zealand?

We emigrated from England to Australia in the late ’40s. Eventually, my mother, my sister, and I went back to the UK by ship. When we got back, I got my first job in Doncaster as an office junior — I had no idea what I wanted to be or do. I’ve got no qualifications of any kind. I was dumb as. I was as thick as two short planks when I was a teenager!

My father, in the meantime, had come to New Zealand. When we were in Australia, we moved all around. While we lived there, I went to 14 different schools. I was tired of travelling. By the time I got [to New Zealand] in ’56, I said to myself, this is it, and I’ve been here ever since.

Eventually, you bought yourself a car?

My first car was an English car; my second car was an English car; then I bought a Citroën. Then I met a fellow called Dave Manson, now my oldest friend. He was a red-haired, blue-eyed oddball.

Dave got me into American cars, and I changed — I got right into hot rodding. I bought a body and a chassis, a Model A roadster. I didn’t have a garage — it was built outside in an alleyway off Dominion Road. I didn’t know what I was doing; I’m totally self-taught in everything I do around here. I finished the car and apparently it was considered to be a good-looking, well-engineered car. I’d built it from scratch, and I made some humongous mistakes — at one point, I put a Studebaker steering box in it, and I had it totally wrong. When I turned the steering wheel one way, the wheels went the other! You learn by doing.

As far as the tools and machinery you used to do the work you did …

Oh, it was very basic. I had a hand drill, and then I bought a socket set. I did it the hard way. If I had to get something welded, I’d just take it to a welding shop and say, “Weld these together for me”.

I finished the car around ’64–’65. There was a business called ‘Metropolitan Rentals’ just around the corner from where I was living on Dominion Road. A guy called Ron Duncan had a workshop in Metropolitan Rentals, and, on the strength of my car — on seeing what it was like as a finished product — he offered me a job. He then set up an engine shop in Onehunga, and offered me a job sweeping the floors; that’s where I started. Back in those days, the engines were Ford 10s and Austin A35s. There was nothing exotic. The machining was very basic. I started by sweeping the floor, but, within five years, I was the foreman. This is my hobby. I get paid to indulge in my hobby.

From there, you somehow ended up getting involved in drag racing?

What happened was that, about ’68, somebody put my name forward for the committee of the NZHRA. I left my name — I was up for it — and I got voted in. The secretary of the NZHRA — Garth Hogan, I think it was — quit a short while later, so the committee appointed me secretary. At the time, the main activities were hot rod shows and rod runs, but we didn’t have a drag strip, and we wanted one. The [NZHRA] committee started negotiating to raise funds to build a drag strip.

We held drags on a public road in Wiri — Kerrs Road — and it was my job to negotiate with the [then] Manukau City Council, do all the paperwork, go to all the hearings, and that sort of stuff. It was ending up that I’d have to take a day a week off work to do NZHRA stuff. As you can’t be the foreman and not be there one day a week, we parted company.

So, I bought my first machine, a portable boring bar, which I found in Waihi for $400 or something, and I started working in a little shed about the size of this [two-car garage].

The gear you’ve got in your workshop now — has that been accumulated from when you first started?

I started working for myself in ’73 — in fact, I’ve probably got an invoice for the very first job I did somewhere around here. I’ve still got the paperwork from when I first started, invoices and stuff. I started advertising in the New Zealand Hot Rod magazine at the same time. Last month, Hot Rod did the special anniversary [edition] for 50 years of publication. They showed the front cover of the various issues, and the first two front covers were hand-drawn pictures of dragsters doing massive wheel stands. The third issue showed an actual car — a hot rod. It was that car [points to photo of his roadster].

Hopefully, you’ve still got a copy of that issue somewhere?

Yes, I keep the special ones right here. August 1967. That was an iconic car at the time. But, again, I did what you had to do. I was still secretary, and went through to ’74–’75, ’cause … what we did, we held drag racing on a public road and charged the public to raise funds, but we needed a club to run the event. [The] NZHRA didn’t have the manpower. Six or seven people in a committee couldn’t run an event like that, so we arranged a deal with [the] Pukekohe Hot Rod Club (PHRC), which already had a couple of members on the NZHRA committee. We agreed that the funds would be allocated two-thirds, one-third — two-thirds to [the] NZHRA, one-third to [the] PHRC — and put into an account kept frozen just for building a drag strip.

We made $12K, and it took a year or two to get the drag strip built at Meremere. It opened in the season of ’74–’75. I said at the time, while we were going through all the hoo-ha of getting a drag strip up and running, as soon as the drag strip is running, I’m quitting — I’m out of this job; I wanna go racing. But I was a year late. I didn’t go racing until ’75–’76. I bought a car from Grahame Berry, and I didn’t have the money — he let me pay him on a drip feed.

So, you bought a competition chassis from Grahame Berry, and you mentioned Garth Hogan earlier — have you been acquainted with those big names right from the early days?

That was the way it was back in those days. We started from small beginnings; there are people who had been in it longer than I had. I think it was ’68 that I was voted into [the] NZHRA, and I quit in ’74–’75. They made me a life member eventually, and then I found a 392 Hemi …

So, you essentially went straight from your street cars into a full-on rear-engined dragster?

I took the roadster to the drags one time. We did a shakedown meeting before the drag strip opened. We ran our own cars — a dummy meeting — and it ran a 14.7 at about 100mph. It was considered one of the fastest street cars in Auckland at the time, ’cause it had a Cadillac overhead-valve V8 with a Paxton blower on it. By building that car, I learnt a lot about engines.

It was a blow-through type blower. All you had to do was to put a boost reference to the intake side of the fuel pump, so the fuel pressure went up with the blower pressure; otherwise, the blower pressure would overcome the fuel pressure and no fuel would get in.

You’d figured all of this out off your own back then?

There was data around. I made a Perspex box, which eventually blew up — but what I learnt on that engine! It was a Cadillac, very rare back in those days, and was one of the first cars in the hot rodding scene with an overhead-valve V8. I used International pistons and bored it out ³⁄₁₆ of an inch, and it made the cylinder walls so thin that, if you made good power, they flexed. When I took it down to the drags for the first time with the top off, I would get to half-track and it would blow all the oil out of the motor, ’cause it was pressurizing the crankcase so much [that] it blew the oil out the breather. So, I learnt a lot about building engines by building my own.

So, you went straight from a street car to nitro? Where could you even source a Hemi back then?

From a guy, Subritzky, somewhere around Western Springs — he was in the marine environment, somehow; he had boats or something. He had a ’57 or ’58 Chrysler car and had the motor rebuilt. It blew up. It didn’t have the gudgeon pins fitted correctly, and they came out and scored the bores, so the motor was dead. I bought it in that condition, sleeved it, and made it work again. I made my own valves — I bought blanks from Auto Trade Supply. Back in those days, you made everything yourself. There were no speed shops to speak of, and importing as we know it now was non-existent.

I took the car down to the drags for the first time, and didn’t know what I was doing. I ran it the first time on alcohol, but I had built it as a nitro motor. I was running 30-per-cent nitro in the end, because, if you’ve got a piston that’s 200 [thou] down, that means the piston is 200 down top-dead centre. That gives you about 5:1 [compression], which is what you want for nitro. Well, I had my pistons 50 thou down, and had very high compression for a nitro motor — 7.8[:1]. If you ran more than 50 per cent or 60 per cent, you just couldn’t tune it. I tried running 60 per cent twice and melted pistons both times.

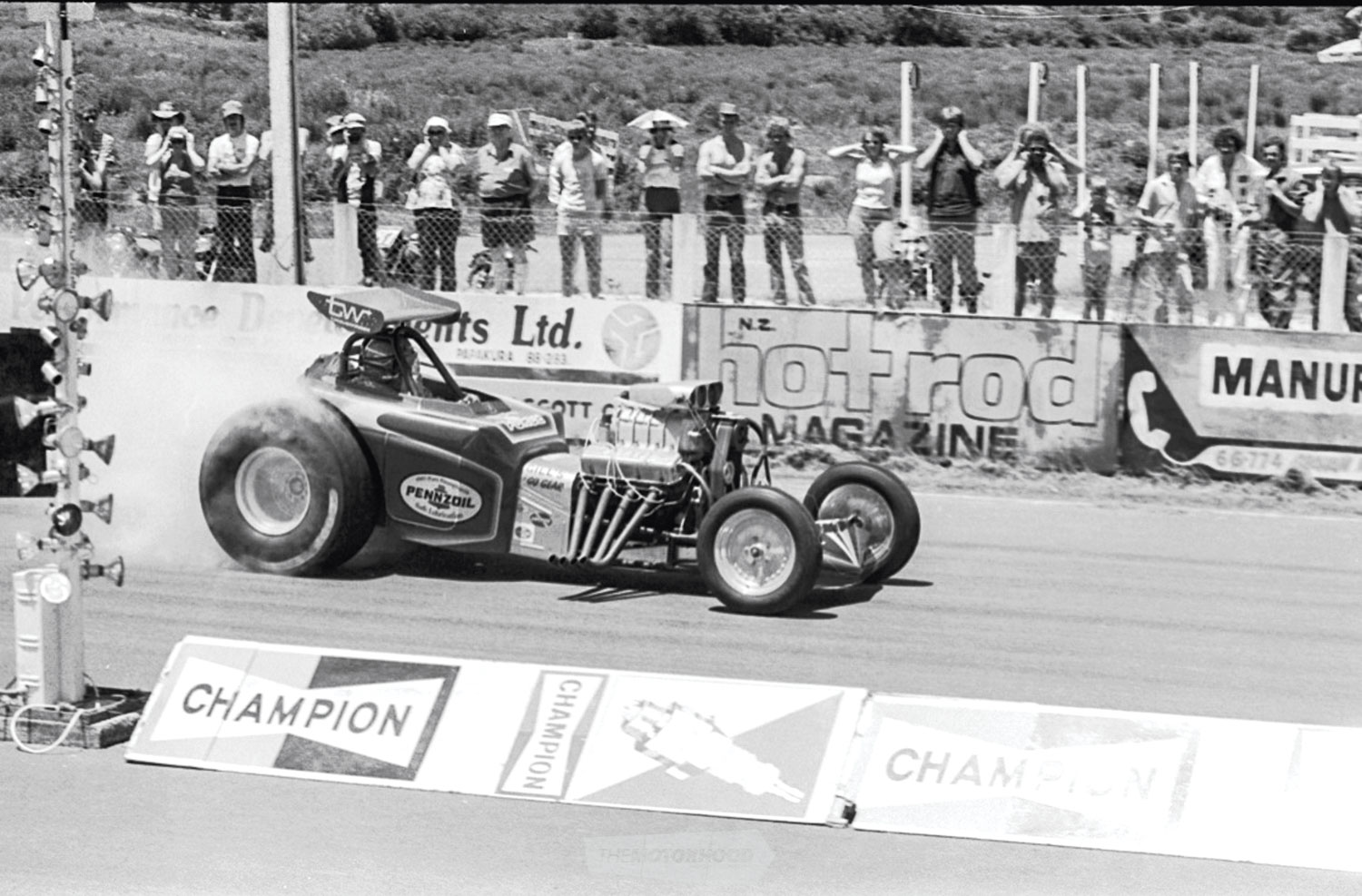

“One of the fuel lines on Mike’s dragster broke, spraying nitro rearwards during the burnout. As it will not combust without compression and spark, the fuel remained liquid, making for a very dramatic photo”

How was the rest of the dragster set up?

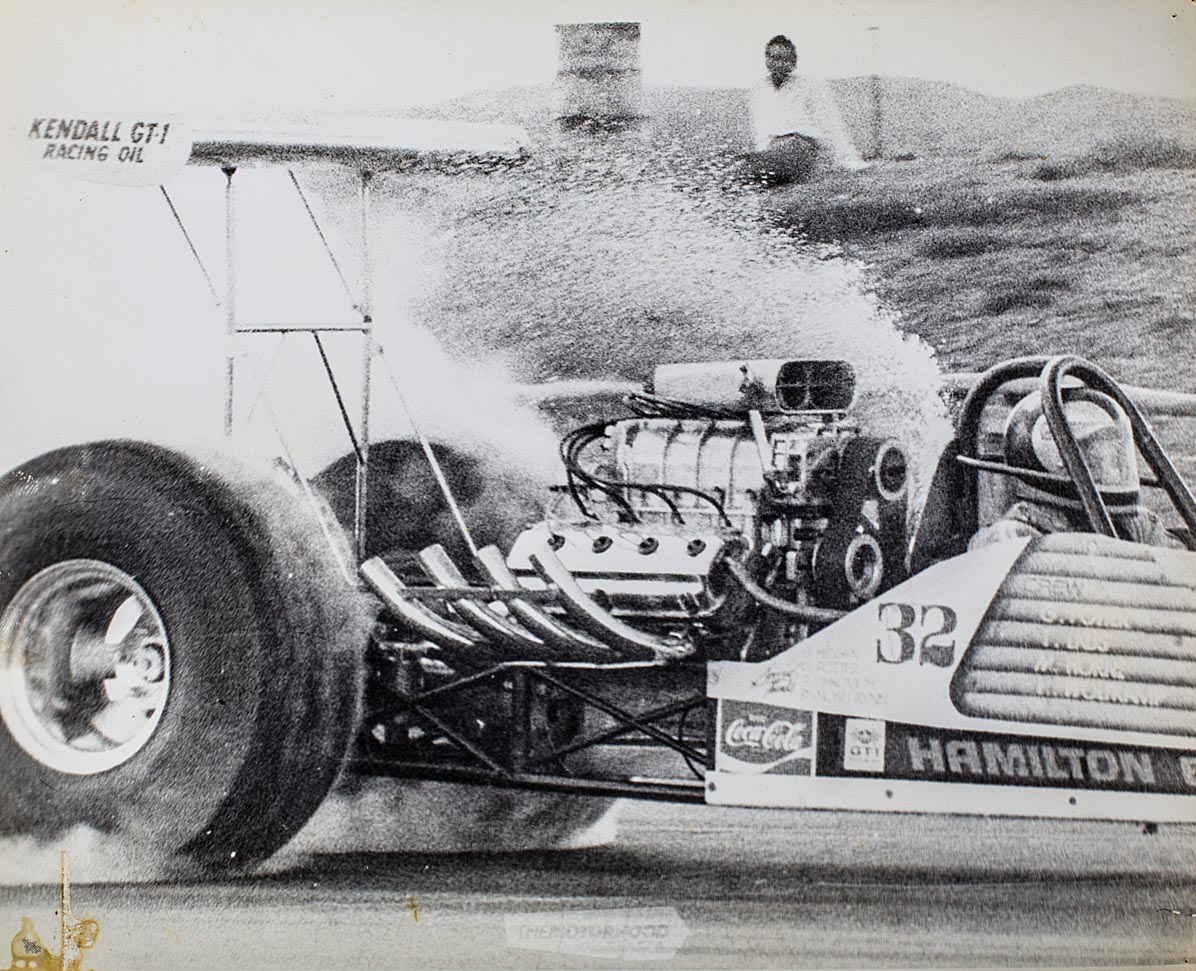

In the beginning, I had a direct drive. Then we decided we’d build a transmission based on a Hydramatic, which is a GM transmission — you’ve got to use the hydraulic pressure to lock the clutch plates up to change gear. So, we built a system of an air accumulator, which we pressurized with a hand lever before the run to get about 500–600psi — then you could change gear three or four times. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn’t, because Meremere was still bumpy and the air accumulator was flexing, so sometimes you’d change gear and it wouldn’t change — it would still stay in low gear. Eventually, we got down to 7.9 [seconds], but my first run was an 8.9. That would [have been] … about ’75–’76, and I gotta tell you — if you’ve never experienced that sort of thing — an 8.9 is nothing in today’s world, but, then, you’d get out of the car and think you could walk on water.

“Nitromethane is dangerous. It’s more dangerous than any drug!”

We built the two-speed, and learnt from that. We took it down to Thunderpark in Hastings with the two-speed, and it went slower. The clutch was set up for direct drive, not for the gearbox, but we figured it out, changed the clutch settings, and went straight from a 7.9 to a 7.3. Huge jump — that’s 6⁄10 of a second, which is massive in drag racing.

Was anyone else running that quick back then?

No — it was the fastest car for three years in a row.

Was everyone else playing catch-up?

Yes, we were all learning. That’s another thing I’ve thought about that time. We didn’t have a drag strip — a proper drag strip — so, when we did get a drag strip, it was the beginning of proper drag racing in this country, and everybody was starting equally. The smarter ones would learn a lot quicker than the not-so-smart ones.

The Meremere track was hard on the cars — you’d bend stuff, and you’d come back after racing for the weekend bruised. I had a helmet that was painted with a fancy paint scheme; the paint got rubbed off each side because you’d bang your head around on each side of the roll cage. You were seeing stars when you went through the traps, but you get hooked on it. I’ve told this guy [points to Reece Fish] that nitromethane is dangerous. It’s more dangerous than any drug!

When my first race car got destroyed, we were the lead feature car for the last race meeting of the season — ’77, ’78, or ’79 — and I’d blown the nitro motor up the previous meeting. So, I put together an alcohol stroker motor, a 354, which was stroked to about 400 inch. I had the block sonic tested for wall thickness, and it came back with absolutely uniform measurements — all the cylinder walls were exactly the same thickness. I was using a scientific testing laboratory in Onehunga for the sonic testing, and they screwed up. The engine lasted two runs. I was with my crew chief, and we took it down for testing on the Saturday, with racing on Sunday — there’s a photo somewhere — and I let the crew chief drive, as he’d busted his balls on the car and deserved a ride. I took the car down the strip first, just to check it out, and there was no timing or ambulance there, just some workers working on the racetrack. I did one run, came back, fuelled it up, did the chute, strapped him in, waved him off … two seconds later, he drove off the racetrack and totalled the car. The engine blew up. Back in those days, we used to run water in the block. So, a rod came out, punched a hole in the block and put the oil and water under the tyres, and he just drove the car off the track. He got a blood nose, that was all, but the car was knackered. Turned out the block had massive core shift and one cylinder collapsed.

Wow! What was next?

I didn’t have a car to race, but a good friend of mine, Kevin Dolores, had an injected Chevy altered. He wanted to put a blower on it, but his wife wouldn’t let him drive it with a blower on it, so he asked me if I would rebuild the motor and drive the car.

I rebuilt the motor — it was just a regular big block Chev; the bores were worn, which was the downfall of the whole thing. We took it to Meremere, and his sponsor, Pennzoil, was there. Kevin called it ‘The Force’ — PennzForce — because the Star Wars movie had just come out. We didn’t know it but, in the process of putting the car together, the centrelines of both the crankshaft and the diff had shifted out of alignment. When you put your foot in and nailed it, you’d get total loss of vision — the car was shaking so badly, you couldn’t see. However, Kevin had his sponsor there so we did one run — 10 seconds at 100mph, just on and off, on and off, on and off. That was the first time we tried to run it.

The car was built to suit Kevin, who was shorter in the body than me. When I did my first burnout, the roll cage was pushing onto my helmet and it came down over my eyes, so I couldn’t see.

That’s still pretty quick, running a 10 like that — not being able to see; just on off, on off, on off …

Hmm, yes, I suppose. I was used to running 7.3s prior to that. Kevin’s altered had Moroso-stamped rocker covers. You can only use screws and a screwdriver-tightening sequence, so you can’t bolt them down. If you look at this photo here [Thunderpark burnout], you’ll see the haze coming off the headers — that’s because the engine was so tired, the oil was starting to leak out of the rocker covers. The engine was pressurizing the crankcase, pushing oil to the top of the motor and trying to force it out of the weakest gaskets in the engine, which are the rocker-cover gaskets. I left the start line and it ran an 8.20, I think, at 184mph or somewhere around there. Just before the finish line — about the 1000-foot mark — the gasket blew totally, covering me in oil, and I couldn’t see, so I hit the chute … I waited for it, hit it again; no chute, can’t see, can’t stop. Back in those days, we used to switch the engine off with the ignition, but the engine was running so hot that it kept on running, ’cause there was fuel there. So, the engine just kept on running, and I ended up going off the track, up a little hill, and launched into the air. I couldn’t see — the helmet had an opaque face shield which was covered in oil, and it changed from medium to light as the car was going up in the air. It went end over end 14 times. It collapsed the roll cage, and I was crushed inside it, so it broke my back.

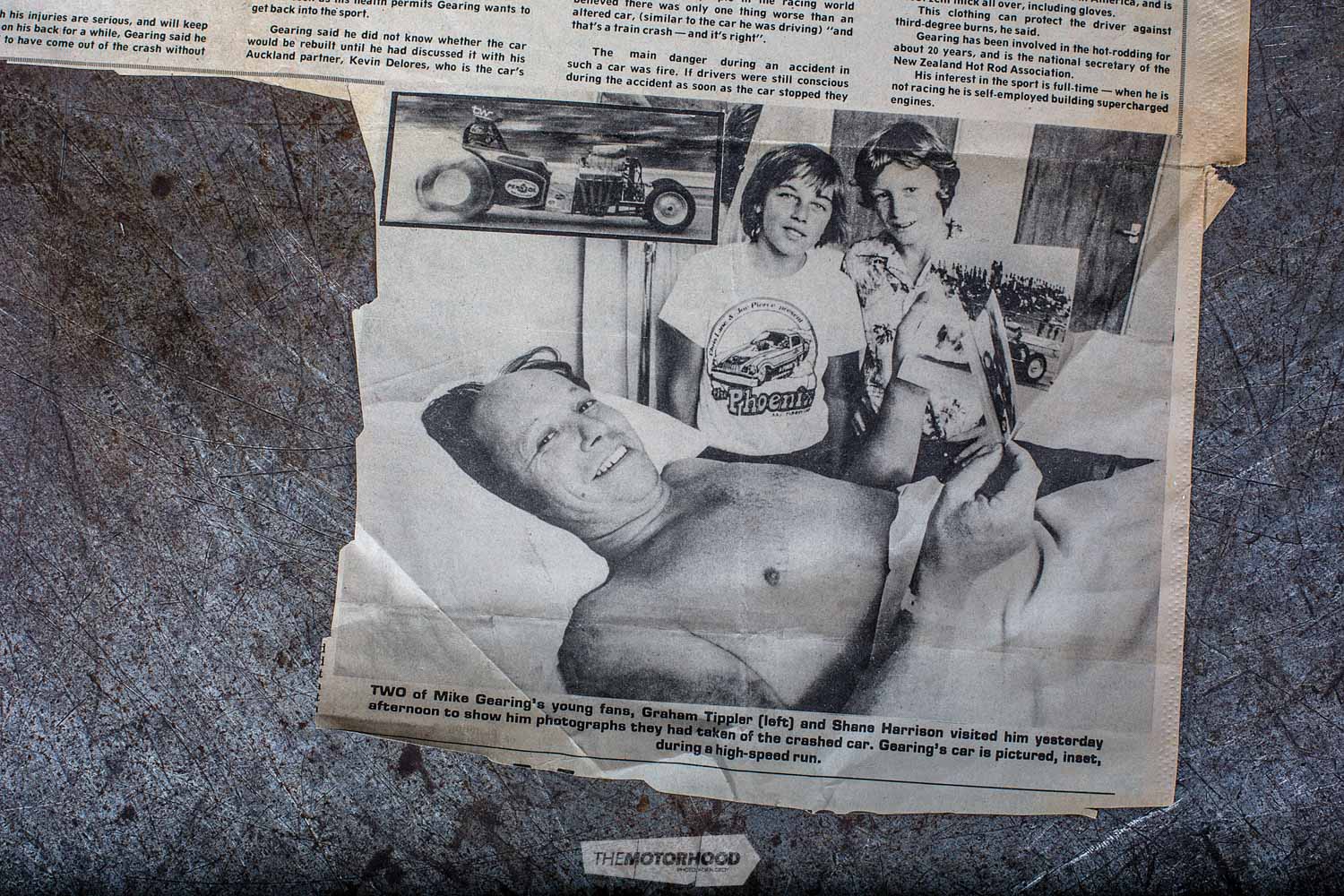

They called it a compression fracture. One vertebrae split the other one open. I had to lie flat on my back for three months. That [photo] was taken just after the event, down at the Hawke’s Bay [Fallen Soldiers’] Memorial Hospital. I’ve got a massive bruise on that arm, and, back in those days, they didn’t have arm restraints — these days you’ve got to have arm restraints, so how I’ve still got these [arms] …

That was in 1980, when I was racing Kevin’s altered. Prior to that, I’d let my crew chief drive my dragster. There’s a moral to that story — don’t let other people drive your car! It’s happened twice, I’ve been on either side of that equation, and both times it failed.

How long was it before you raced again?

I went back to the racetrack in about 18 months. In that time, I’d pulled my ’32 Ford out and I rebuilt that car as a bit of therapy. I built a new race car, a new trailer, and I got to the last meeting of the season at Meremere. I was racing Lewis Wymer again, and I holeshot him by 2⁄10. Then you just carry on.

We [had] learnt about transmissions, and when I built the second car I got a three-speed Lenco, ’cause I thought, If one gearbox drops us 6⁄10 of a second, what do you do with two gearboxes?

How accessible was gear like the Lenco back then?

A pair of brothers in Hamilton had bought a three-speed without a reverser, and I bought it from them for $4K or $5K. So, I ended up running the three-speed, and it was a manual with air-operated shifts, so we didn’t have to worry about pumping up the air-accumulator. The problem with running a three-speed transmission — and I’d changed motors from 392s to a 426 — is that we are such a small country, and with limited experience at the time, that most people got their knowledge from overseas. My combination was so unique, no one had done it before, so it was trial and error.

Garth used to go to the States several times a year, and [he got to] know the right people. Sometimes, he’d bring them over. He brought Gene Beaver over to my workshop one time — cleaned me out of tequila!

So, did you end up gaining knowledge through these people as well?

Well, no, that’s what I’m saying — Garth ran a traditional deal. He ran a two-speed, 85 [per cent] in the tank, and many people in the world were doing that. I was running a three-speed, and I ran on a budget — a drum of nitro was four grand back then, and if you’re running 90 per cent, you’d get four runs out of a drum. But if you run 50 per cent, you get 10 runs out of a drum. I could make a drum of nitro last me all season — not like somebody I know [looks at Reece Fish; laughs].

Your name is often associated with Reece’s these days. Where does he come into the picture?

I met Reece when he rang me one time. He’d bought the ’56 Chev. I’ve been involved with that car for three different owners — the first was a guy called Mike Crow. He sold it to Tyrrell, Reece’s cousin, who wanted to put a blower on it — he’s a bit of a lead foot. Then, Reece bought the car.

He rang me and said, that there was a bit of a problem with the car, so I asked him what it was.

He said, “Well, it backfires at 130mph; what would that be?”

He brought the motor in, we pulled it apart, and, sure enough, there was a cam lobe gone. The valvetrain was knackered, so I estimated a cost for rebuilding it. I think Reece went home and told his mum and dad, and they were horrified! They came back and checked me out, but apparently I got the stamp of approval; it started from there.

This was some time in the early ’90s?

Well, we’ve been here 29 years, and it was shortly after that, so I guess we met about 28 years ago. It started from there. He’s a petrolhead and he’s picked up the bug; it’s as simple as that. He spotted a dragster for sale in Australia, so Carl Jensen and I went with him to look at it.

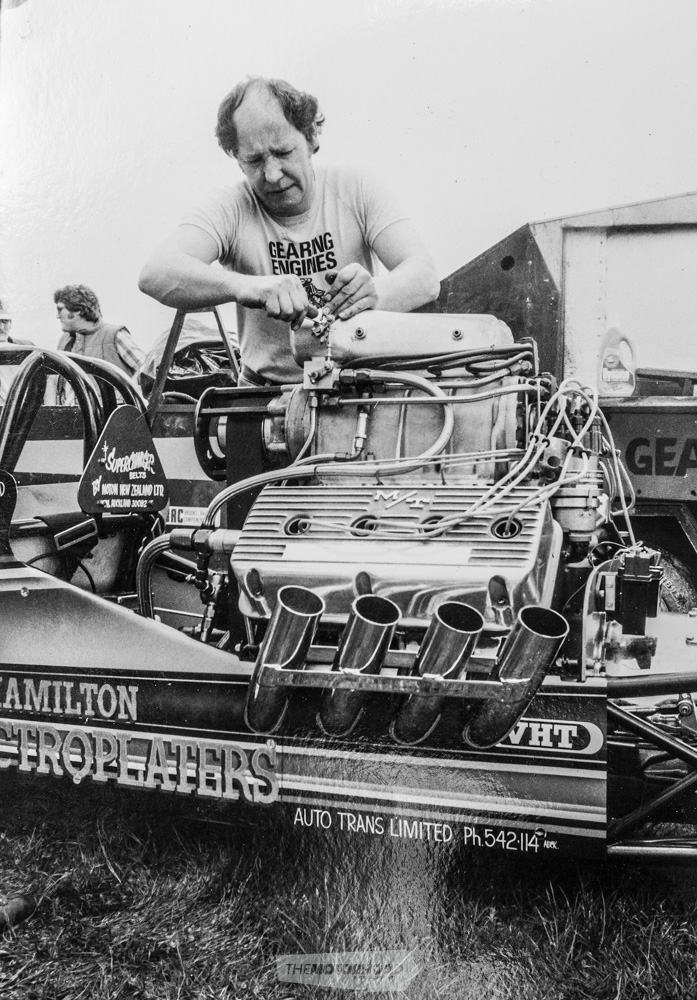

This is the car that would end up becoming the Fish Family Racing top-fueller?

Yes, it was the Bob Shepherd car. Bob Shepherd decided to retire, and he wanted to get rid of everything. It was Reece’s deal, so Reece bought the dragster and all the spares, including junk, the truck, the trailer — everything. He brought it back here, and we all started a massive learning curve, because this type of car was totally different from the dragsters I used to race. I was lucky if I made 1500hp — we’re talking 8000 here.

Was that your next big step up, as far as nitro motors go?

No, prior to that, it was Athol Williams with his bike. He was my crew chief on the second car in the ’80s. When I quit, we sort of parted company for a while; he ended up buying a property down in Pokeno. Anyway, he gave me a call one day, saying, “Mike, I’ve just ordered a bike from England. It’s a top-fuel bike” — and he just left the question hanging in the air, like are you interested?

“Athol was another who got hooked on nitro, worse than I did.”

So, I went and looked at it, and he formed a team. Athol is a smart guy — he knows about clutch settings and fuel and stuff like that, so, between us, we got the bike running. Originally, it was running a four-valve head — twin-cam four-valve — and the valves were really little, like a tiny nail. It took Athol quite a while to get the hang of keeping the throttle wide open. If you back off on a bike like this, the engine goes lean when you’re out and in, out and in, and the porcelain falls off the spark plugs, goes through the valvetrain, and bends all the valves every time.

In the end, we rebuilt the motor. It was based on a Suzuki head when he bought it, so he bought a Vance and Hines twin-cam head — two-valve. The block was billet; everything was billet. The crankshaft was made by Roger Bloor, a very talented machinist — he made the crankshaft and everything out of billet.

That lasted for about five years. Athol started to race in Australia; he’d take the bike over there, the whole truck and trailer unit — we’d do that eight times a year. It was a five-day undertaking for us to fly over, set the bike up, set the rig up, race, service the bike ready for the next meeting, pack it up, [then] come home. We did that for five years, and Athol slowed down. He was another one who got hooked on nitro — worse than I did.

Didn’t he end up running his all-time personal best over in Australia?

Yes, I think it was 6.20, because my best was 6.30 and he wanted to beat it. I think he ran a 6.20 in Sydney, at 220 or 230mph, and there is an incredible photo — he was at half-track at Sydney, the front wheels are off the ground, and you can see his eyes stuck out through the helmet, and he’s going balls-out.

On January 8, 1984, Mike ran his first 200mph quarter-mile in the same pass as his first six-second pass — a huge achievement, especially for the early ’80s

The run prior to that: we were at the start line waiting, because it was our turn next, and Jay Upton went out in his fuel bike, and he came off at the traps at 200-plus [mph]. I went up to Athol and said, “What do you reckon, Athol? You gonna park it for a while?”

He said “No” — he went out and ran that number. I wouldn’t have blamed Athol, because I’ve seen some things — when you see somebody you’re connected with get into trouble big time, it turns your stomach.

I remember I was in the staging lanes at Meremere when Garth was racing the funny car, and he had a transmission explosion. It was an overdrive transmission, and if the sprags fail, the thing just free-wheels and goes to 30,000rpm or something, and it just flies apart. In a funny car, you’ve got your feet to either side. I heard Garth do his burnout; I was in my car when I heard the bang and saw this piece of shiny steel go flying through the air over to the canal or somewhere.

I thought, “Shit, that’s Garth’s feet gone,” and I felt sad; I had to force myself to stay in the car and go down the track.

It must have been a very long minute, waiting for that to be over and done with?

Yes, well, it’s what you expect. When you’ve got your feet either side of the transmission, even with the blanket on, for that piece of metal to come out when your feet are right there. I believe it broke part of his foot.

Sort of like the Don Garlits incident?

Yes, he lost part of his foot. Someone actually found it and gave it back to him, according to his autobiography. So, the bike racing finished and Reece came along with his Chev [street car], trying to go quicker and quicker and quicker — we got that up to 2000-plus horsepower.

How did you find that?

It was simple. You keep building better and stronger; that’s the name of the game. You don’t stand still, because if you stand still, you’ll get overtaken. We built what I call ‘a clean sheet of paper’ kind of motor. Instead of building a motor because you’ve got this block and those heads, and this guy’s got that and that guy’s got this; we buy the stuff and put it together, but it’s not perfect. You get a clean sheet of paper, and you write what you’re going to buy: this block, and this, and this, and this. You plan the motor, piece by piece. We built the motor and we were going for 1500–1800hp. That was around 2005–’07.

Is it still the same bottom end?

Reece Fish (RF): Originally. Basically, the car evolved as it went along. It had the blown motor, which is what the car was, and we went as far as we could with the supercharged motor on petrol or a petrol-based fuel — as far as we could go without melting it down. So we pushed it, and the only way to go faster was to go methanol, which I didn’t want to do because that’s not street. The whole point of the car is to keep it street legal. We got a 9.0 out of it with the supercharger and a 10-inch-wide tyre on it.

My original plan was to go to a ProCharger, because that’s, kind of, the next-most-efficient supercharger. Then we got talking to a guy in America, one of Carl Jensen’s friends, and he said, “Don’t bother wasting your money. Spend your money now and turbocharge it.”

At that point, there was no other turbocharged V8 around [in New Zealand]. Graeme Bates down the line was playing with them, but that was about it. No one had a twin turbocharged V8, and that kinda appealed to me, because I like to do things differently to everyone else. That’s why we went down the turbocharger route.

MG: The reason we pursued that route was because the BDS 10-71 was dynoed every time; it made horsepower, we’d take it to the track, and it would melt a piston. The moral of that story is that you don’t race the dyno. The dyno is not a racetrack, and, on race day, it’s different.

RF: We were pushing it as hard as we could; we were starting to melt stuff — we’d burn the engine up because you’re at the limit of what it can handle.

So, this whole time, with the blower motor, you were working with Mike, and that continued with the turbo motor?

MG: No, my knowledge of turboing is limited. He did his own homework on that — he and Carl [Jensen], between them.

RF: Originally, we used the same engine we had the supercharger on, so I pulled the supercharger off and we put the turbo induction on, fuel injected it, and put the turbos on. On the dyno, it picked up 500hp without anything else being changed. We raced like that for a few years, just learning, you know — I think the car ran an 8.3 with that combination.

Light-years ahead of everyone, even today …

RF: Yes, and then, basically, once we understood how the turbos worked — they’re a different animal — we started again with another engine, which is the motor that’s in it now. It’s all billet aluminium, specifically built for the turbos.

So we just repacked the chute, went out, and ran a seven-second run … I’ve got that $500 grin on my face

It still had the Gearing touch?

RF: Oh yes, for sure …

MG: No, you basically built that thing yourself, Reece! He’d become competent enough, years ago at that point, to build his own motors. We confer frequently. He asks me questions sometimes that I’ve forgotten that I know the answer to. I’ve gotta struggle and go back to some books and think it through for a while.

So, over this whole span of the last 25-odd years, both of you have been working together, and your knowledge, Mike, has basically been filtering through to Reece?

MG: Yes, sure, he’s been up here, and I’ve shown him how to use every machine in the shop. He knows more than I do, now. Which is how it should be, because you learn from the previous generation.

So, he’s got your knowledge, plus all the turbo and electronic-fuel-injection (EFI) stuff?

MG: Yes — tell them about how you redesigned the cam for your Chev.

RF: Well, the cam that’s in the Chev at the moment is my own design …

MG: … and it made more horsepower.

RF: We learned over the years.

So, has all of this has built up so you can now look at each part of an individual engine and say ‘that could be better’, or ‘that’s not working properly’?

RF: Yes

MG: It’s great to watch. I get great satisfaction out of him, Carl, and what they’ve done.

Reece, when you showed us your top-fueller, you knew every single part in the thing.

RF: Yes, [a] top-fuel [car] is a different animal from a street car, you know. In a top fuel car, basically everyone on the crew has to know — if something were to fall off and you hold it up, you have to know where it goes.

MG: I told Reece that when he bought the car, because that was the way I operated with my dragster. You gotta know every nut and bolt on the car, and you need to be able to sit in the cockpit and do everything with your eyes closed. Practise.

You gotta know every single thing on the car, so you analyse it instantly. I can give you an example — it’s been printed before. I didn’t have reverse gear in either of my cars, and one of the guys on my crew was a fellow called Maurice Horne. We were racing in the left-hand lane at Thunderpark, and I’m sitting in my car like this, and he’s pushing me back. I was looking down the track as I was being pushed back, and I saw a big bolt lying on the track, so I tapped Maurice’s arm and pointed to it, and he went jogging back and picked this bolt up. He looked at me, looked at the car, and threw it away.

Seven seconds later, I went through the traps at nearly 200mph, the parachute came out and fell to the ground. It was just a big old bolt [for the parachute mount], and obviously somebody hadn’t put the nut on the end, and it fell off on the burnout.

How did that end up going?

Oh, there’s a half-mile of seal, but the disc brakes are useless at those miles an hour. I managed to slow it down, but it was off the track into some scrub, and there was a little culvert, a ditch, coming up and the car was only this far off the ground. I knew that if the car went into that ditch, I’d damage it severely, so I did a movement and flipped the car around 180 [degrees], pointing back the other way, and it didn’t fall over.

The car was all right after that?

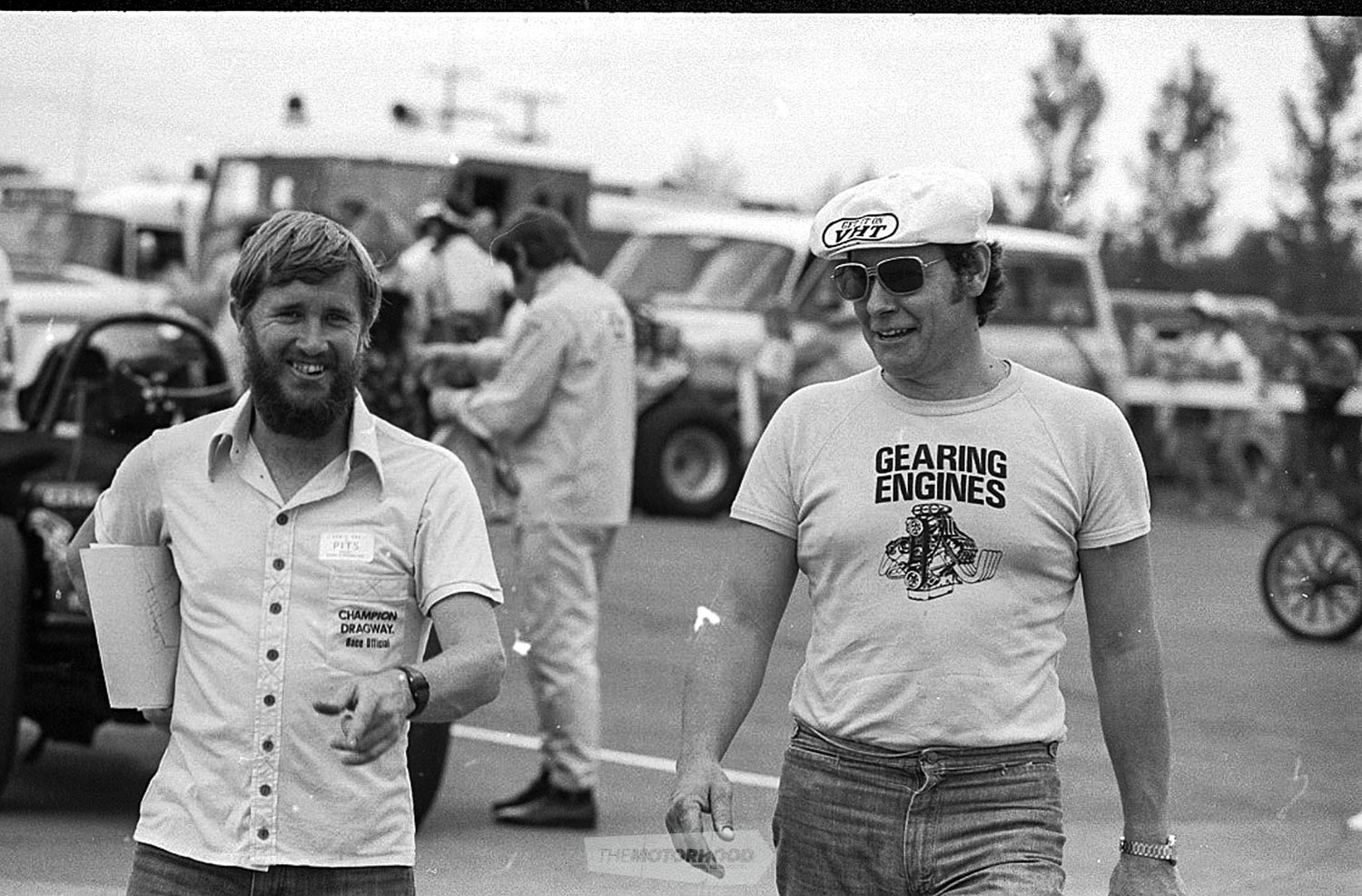

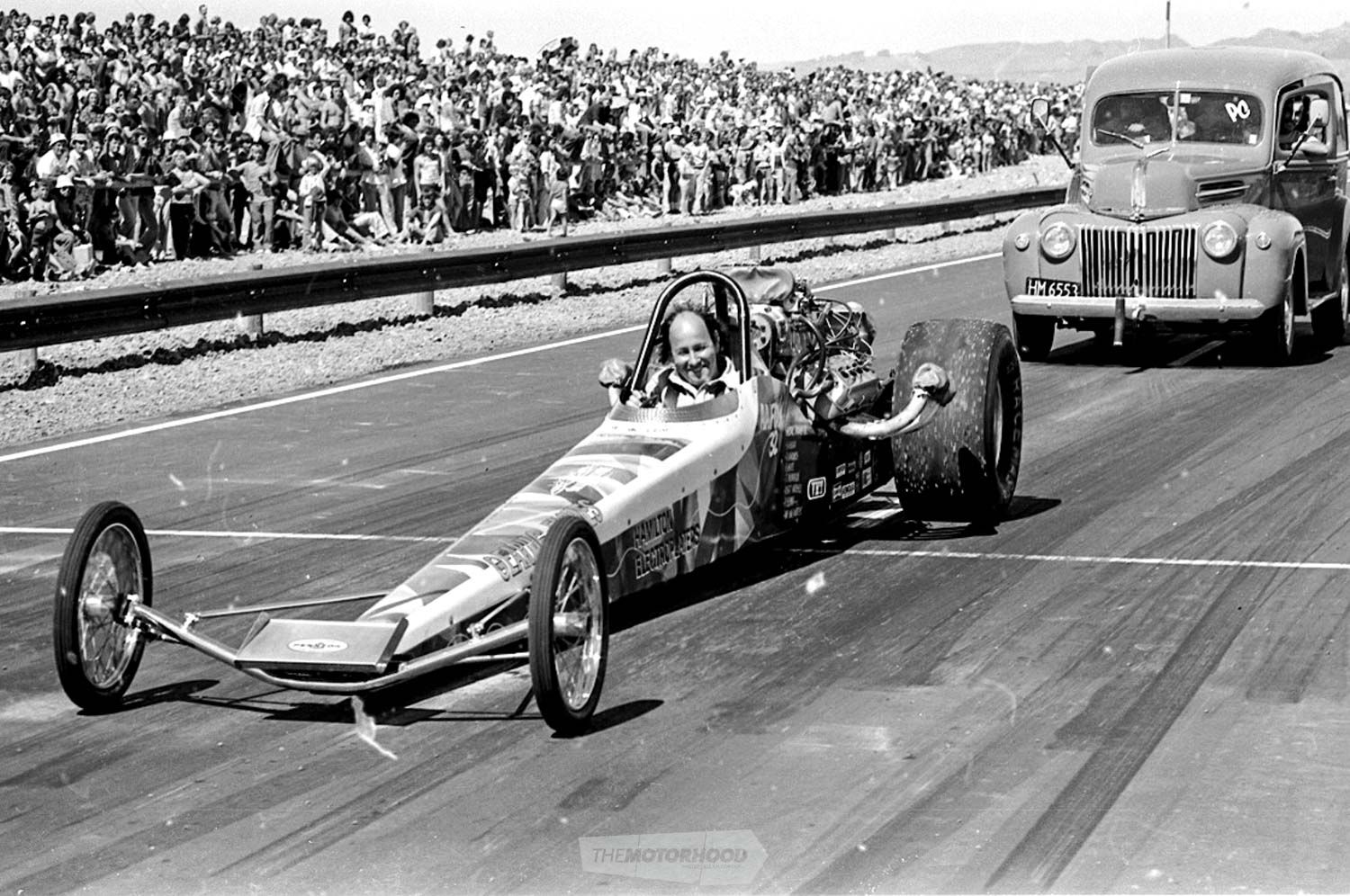

Yes, we found the bolt, put it back in, and raced again. There’s been a couple of incidents like that: another time at Thunderpark — see that photo there [gestures at photo]; I’ve got a big cheesy grin on my face; well, we’d both — Bob Clarkson and his driver Lew Wymer, and I — we’d both run seven-second passes at Meremere the previous week, and there was a cash prize for the first seven-second run at Thunderpark. So we both went out to race, and we both had these seven-second cars on the start line. I did my burnout and the parachute fell out. One of the crew indicated that I shut it off. I looked across at Bob and Lew, and Bob was telling Lew to get into stage. So, he went in to stage, nailed it, and the diff went bang! So, we just repacked the chute, went out, and ran a seven-second run. They brought me back down the racetrack instead of the return road, and I’ve got that $500 grin on my face.

We’ll have part two of this interview in the next issue of NZV8. Our thanks to Mike Gearing and Reece Fish, for taking the time to be interviewed; John Lindesay, for making it happen; and Allan Porter, for supplying original photography.