When Donn had a drive in the Roly Levis Brabham in 1964 he had little idea of the car’s unique heritage

Youth pays scant regard to history and heritage. When Roly Levis invited me to drive his Brabham BT6 National Formula open-wheeler 48 years ago, I placed little importance on the car’s colourful past. And at the time, of course, there was no way of predicting the Brabham’s equally eventful future.

It was, after all, simply a 1.6-litre Ford twin-cam engined racer that Levis had imported and was campaigning successfully on Kiwi circuits. Decades later, I realised this Brabham – chassis #FJ-9-63 – was more important than it seemed at the time, since it was the actual car that launched Denny Hulme’s international career in 1963. Not only that, between 1964 and 1969 this Brabham would campaign no fewer than 24 Tasman Cup championship races – more than any other car.

Track Test

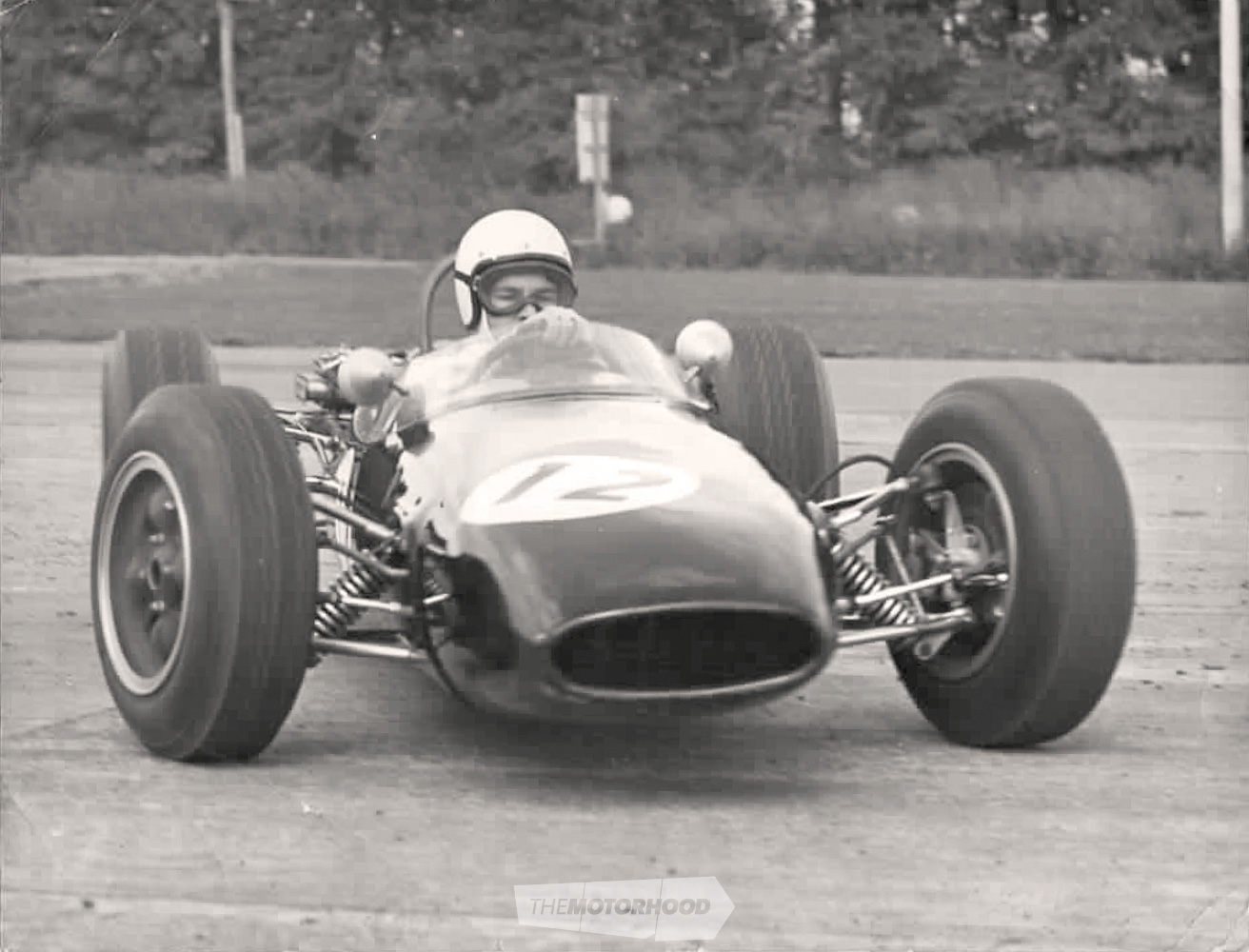

I was still a teenager when the offer came to sample the black Brabham at the Rukuhia airstrip in 1964, long before the site became Hamilton’s domestic and international airport. Roly was clearly a trusting sort of chap who reasoned the location afforded few obstacles for a young journalist to hit in his car. The outcome would form the basis for articles in Motorman magazine and The Auckland Star, the long-gone evening newspaper that provided much needed competition for The New Zealand Herald.

Climbing aboard was a matter of grabbing the low roll bar and swinging both feet into the skimpy cockpit. Lying almost flat on my back in the cradle seat with the four wheels looming high above, and the softly padded steering wheel at arms’ length, I contemplated the 10,000rpm tachometer, water temperature gauge and combination oil and oil temperature gauge. Nothing too complicated there.

On the extreme left was the fuel pump switch and, to the right of the cockpit, the gear lever. Levis occasionally ran the twin-cam Ford-based Cosworth 1498cc engine to 8000 revs, but usually adhered to a safe limit of 7500rpm. Oil pressure ran between 4.0 and 4.8 bar (60 and 70lb), and the motor settled to a steady 700rpm after a short warm-up period at around 1500rpm. The engine was producing 113kW (152bhp) which was reckoned to be above average.

Releasing a safety catch allowed first gear engagement, a flick of the fuel pump switch and the engine soon fired after a brief push-start. Roly suggested the use of second gear for all take-offs and, after one stall, the Brabham was away. Too much sudden throttle movement affected the fuel mixture, resulting in violent jerking, but once running smoothly the twin Weber carburetted Cosworth engine provided an impressive lift.

Tipping the scales at just 410kg, the Brabham thrived on high revs, and the five-speed Hewland Mark 5 gearbox was remarkably easy to use, despite the lack of synchromesh. At 161kph (100mph) in fifth, with the tacho around 5000rpm, the car just seemed to be cruising, with the promise of 241kph (150mph) top speed in the wings. On the Pukekohe back straight, Roly regularly posted 7600rpm in fifth, or 230kph (143mph), but said he had topped 241kph on some of the faster Australian circuits.

I ended the day in awe of the engine’s impressive power and the great sensitivity and responsiveness of the chassis. The Brabham was also user friendly, although to engage it in anger might well have spelled a different message.

The Early Brabhams

In a 12-year period until 1973, Brabham built a remarkable 624 racing cars, of which just 15 were sports cars while the rest were single-seaters. A development of the BT2 Formula Junior open-wheeler, the BT6 was one of the most successful Brabham models. A total of 20 BT6s were made, and drivers included Mike Hailwood, Gavin Youl, Silvio Moser, Jo Schlesser, Graeme Lawrence and Andy Buchanan. Most of the early chassis were powered by the Holbay-modified Ford Anglia 105E 1100cc motors for Formula Junior racing before the upgrade to the 1.6-litre Ford twin-cam and, in 1964, the car was adapted to F2 and F3 specifications.

With its space-frame chassis and glass-fibre body, by Specialised Mouldings, the BT6 is a conventional package using Girling discs all round, with the rear brakes mounted outboard for easier maintenance, better cooling and to avoid possible problems with oil on the brakes. Donor suspension parts from the Triumph Herald and Ford Cortina were used, the rubber driveshaft universals came from a Lancia Flavia while the steering rack is an original Brabham part as are the 13-inch-diameter magnesium wheels. The front suspension comprises double wishbones, an anti-roll bar, Triumph uprights and coil springs. At the rear are lower reversed A-arms, a top link, double trailing rods, an anti-roll bar, Brabham magnesium uprights and coil springs.

The half shafts have Metalastic inboard joints, eliminating sliding splines. Progressing from the BT2, the BT6 has a revised seating position and lower screen, and the handsome body shape still looks good. The enclosed battery is carried under the driver’s knees and a light alloy fuel tank sits amidships and embraces the rear of the driver’s seat.

Denny and the BT6

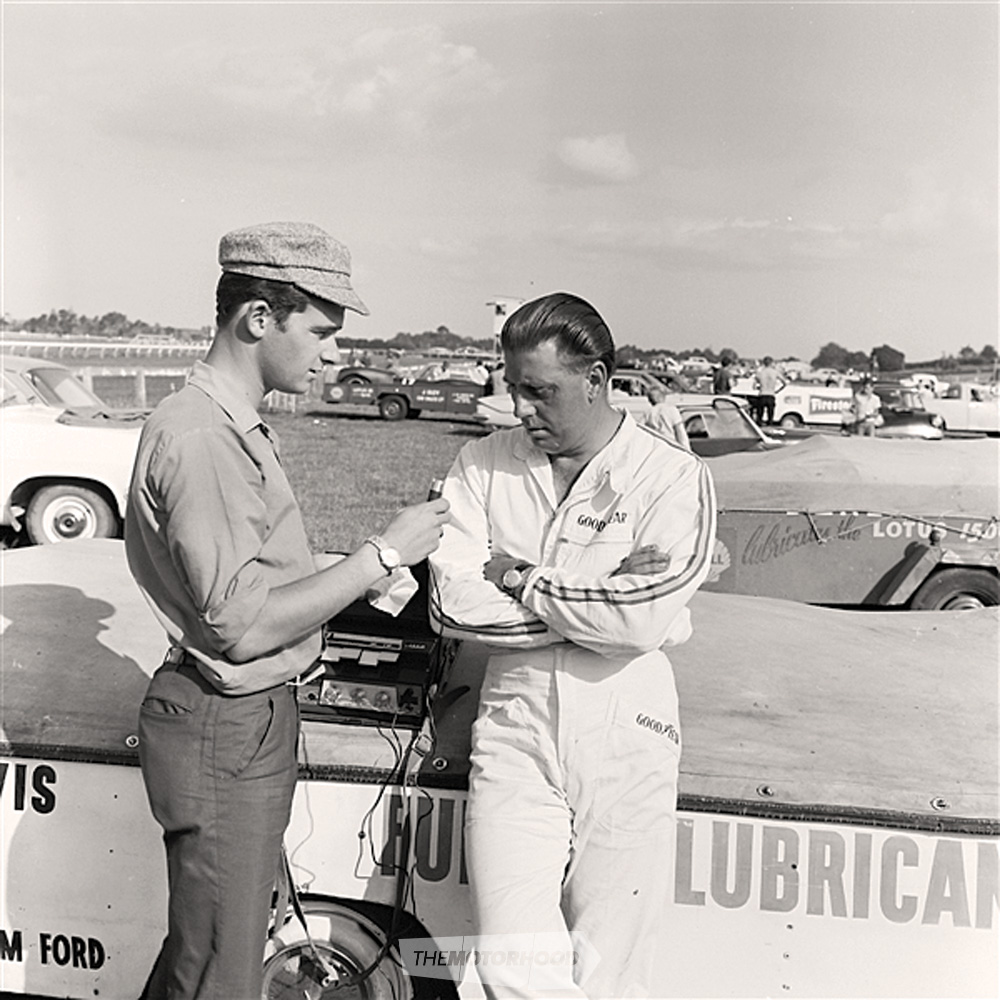

A crash in FJ-9-63 on the last lap of the Formula Junior race at the Silverstone British Grand Prix in July 1963 cost Denny Hulme the UK title that year. Peter Arundell in a Lotus 22 beat Hulme by one point, but the New Zealander had an outstanding European summer in the car. At 14 meetings in 1963, Denny and the works Brabham scored six wins, four seconds, one third and only three non-finishes. He also set five class lap records and his pace was remarkable. On the high-speed Rheims road circuit in France Hulme not only won the FJ event, but recorded the fastest lap at an average of 185.17kph (115.06mph).

Denny was up against a class field throughout the year, including Aussies Frank Gardner and Paul Hawkins, both in similar BT6 Brabhams. Even though the Hulme car was works-supported, Denny was on a tight budget that necessitated watching every penny. Fortunately, he had a modest fuel contract. After each event he filled the race car and topped up half-a-dozen five-gallon cans to get him to the next race.

He arrived at Monza only to find he had confused dates and hadn’t entered. Instead, he should have been at Rheims in France the same weekend, and an overnight dash saw him waiting at dawn for a French petrol station to open. The wily Kiwi had to scratch through a shoebox full of every denomination of European coins to find enough francs to pay for fuel.

With the ending of the Formula Junior class, the BT6 series took on a new role. The Hulme BT6 became the first Brabham to be fitted with a 1.6 twin-cam engine and was sold for £1600 (around $3200) to Alec Mildren Racing in Sydney. These days the going rate for a BT6 is around $80,000!

Tasman Career

The car was freighted to Australia late in 1963. Gardner recalled in 2000 how he tested and adjusted the suspension to suit the twin-cam’s extra power and weight. He crashed the Brabham on his first competition outing at Catalina near Sydney in January 1964 before racing the car in the Australian GP at Sandown Park, and winning the 1.5-litre class at Lakeside and Longford in the 1964 Tasman series.

Australian Charlie Smith drove the car in five races under Alec Mildren’s banner, scoring one victory. When Levis had his first race in FJ-9-63 in September 1964, the Brabham was still entered by Mildren. It was a good start for the Putaruru driver, for he was third in his debut drive at Sydney’s Warwick Farm behind Greg Cusack and Arnold Glass.

In his first New Zealand outing with the car at Pukekohe in November 1964, Roly finished second to the larger Climax-engined Brabham of Jim Palmer, but a week later broke a universal joint at Renwick. He took the black Brabham to a well deserved victory in the Fred Zambucka Memorial race at Levin, and at the 1965 NZ Grand Prix meeting fought off a strong challenge from Aussie Leo Geoghegan’s 1.5 Lotus to win the Pukekohe feature. An early race shunt with Bruce Abernethy’s 2.5 Cooper in the GP put Roly out of contention.

Levis finished sixth overall at the Levin, Wigram and Teretonga internationals before crossing the Tasman for Warwick Farm, where rear suspension damage in practice forced an all-nighter. The work paid off, however, with a lap record and class win in the Tasman Cup race. A week later at Sandown Park, Roly finished seventh and first in class, but he couldn’t fathom the handling problem in the 30th Australian GP on the notorious Longford road circuit in Tasmania a few days later. An unknown broken differential carrier was causing massive understeer, and this was always going to be a meeting Levis would prefer to forget.

Coming through from the tail of the field was young Melbourne driver Rocky Tresise in a 2.5 Cooper Climax, who was fatally injured when he crashed heavily off the narrow road circuit while attempting to pass Levis. Then less than half a lap from the finish the diff carrier finally broke. Roly crashed through a fence and was admitted to hospital with facial injuries. He was still classified a finisher, and second in class.

Roly’s talents consolidated during the 1965–’66 season when he won New Zealand’s National Formula championship, following his acquisition of a new Brabham BT18 which would win him the premier Gold Star title for the 1966–’67 summer. In spite of running against larger capacity cars, the Levis BT6 was second at Renwick and Levin late in 1965, fourth at Pukekohe, eighth in the 1966 GP, fourth at Levin, and third behind Jackie Stewart and Jim Clark in the Vic Hudson Memorial the same day. He was consistently top 1.5-litre car at these meetings before his Australian excursion that saw the Brabham seventh overall and first 1.5-litre car at Warwick Farm and eighth (second 1.5-litre) at Longford.

The car suffered brake troubles at Pukekohe in February 1966, and the following month Roly found himself in hospital with back injuries after flipping the BT6 while practising at Levin’s tricky Cabbage Tree corner. This necessitated a major rebuild, updating the car with BT9 parts. At the same time, Levis was also rebuilding BT6 chassis FJ-18-63, the car in which Bill Caldwell had been killed at the January 1966 Teretonga meeting. This car had originally been imported and raced by Andy Buchanan.

Beautifully Restored

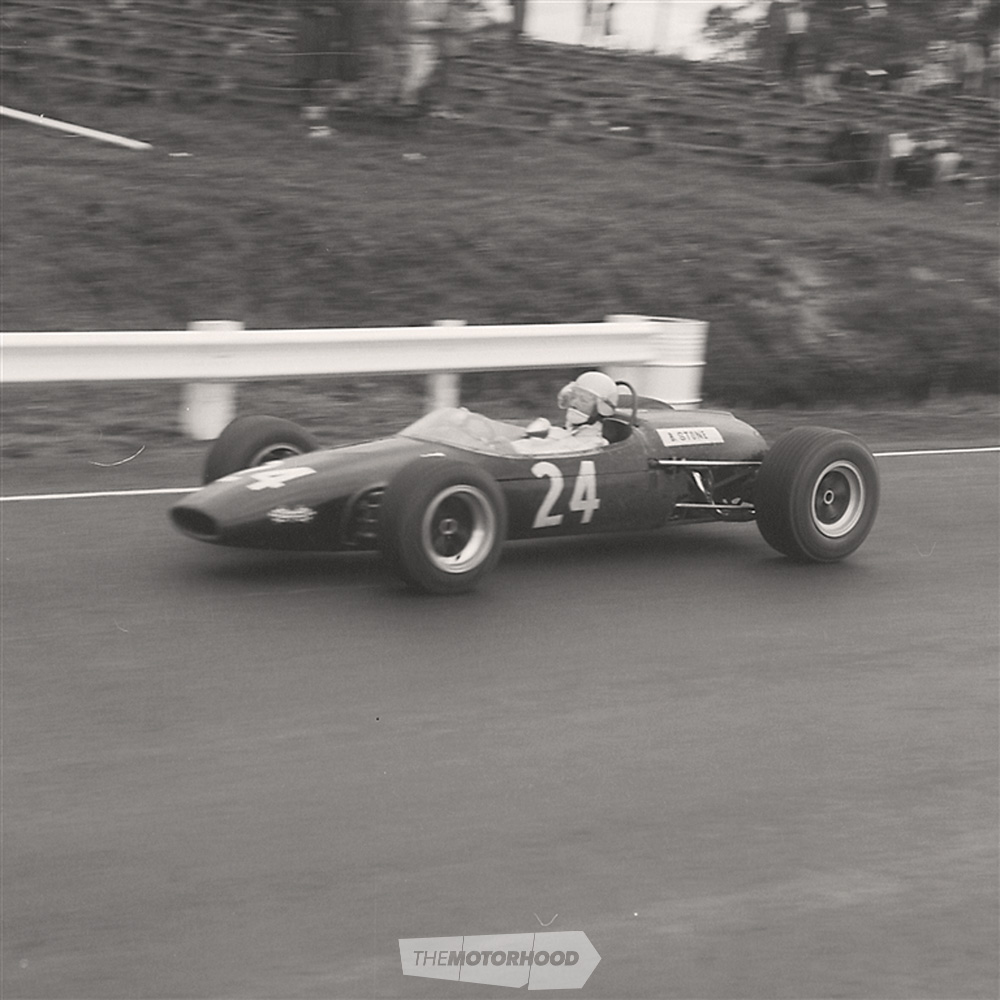

The ex-Hulme works car was sold to Bill Stone, who had his first outing with it at Pukekohe in November 1966. Bill enjoyed mixed success, with the Brabham suffering yet another accident – this time at the Timaru street races in 1977. Stone clipped a kerb and flipped upside down against a concrete wall but, like the phoenix of legend, #FJ-9-63 was rebuilt for the 1967–’68 season.

The car was sold to Jiggs Alexander, and his first of four meetings was at Bay Park in December 1968. He last raced it in March 1970 – and 31 years later, in late 2001 following its complete restoration, Australian Ian McDonald ran the Brabham at Sandown. The car’s current owner, Ed Holly, who purchased the BT6 in 2006, says it has won the Jack Brabham trophy on three occasions, twice at Tasman revival meetings.

Today Roly Levis lives in retirement in Tauranga, and can ponder on that special black Brabham with affection. Levis was one of six drivers to race the BT6 prior to its 2001 restoration, but drove it at more meetings than anyone else. He campaigned it in a remarkable 28 races, while Bill Stone was almost as busy after running the Brabham at 24 meetings.

Today, the beautifully restored machine competes in historic races in Australia, and appeared at the Hampton Downs revival meeting three years ago. Ed Holly had hoped to bring the car from Sydney for the Denny Hulme Festival, but sadly these plans were shelved. However, this high-achieving Brabham will always have a special place in the annals of motor racing, both here and in Australia.

This article originally appeared in NZ Classic Car issue No.265 — to get your hands on a print copy of the magazine, click on the cover below: