We send the spotlight under the car to focus on the drivetrain, covering everything from the engine’s crankshaft to the driven wheels

The drivetrain is one of those areas that are mostly maintained ‘on condition’. That is, you pay attention to it only when prompted to, usually in the form of a funny noise or vibration.

There’s a good reason for this. The components are big and sturdy, and, as long as the right parts are bathed in oil, they will hum along happily for thousands of kilometres. Even oil changes are few and far between, as they don’t have to deal with high engine temperatures or soot particles.

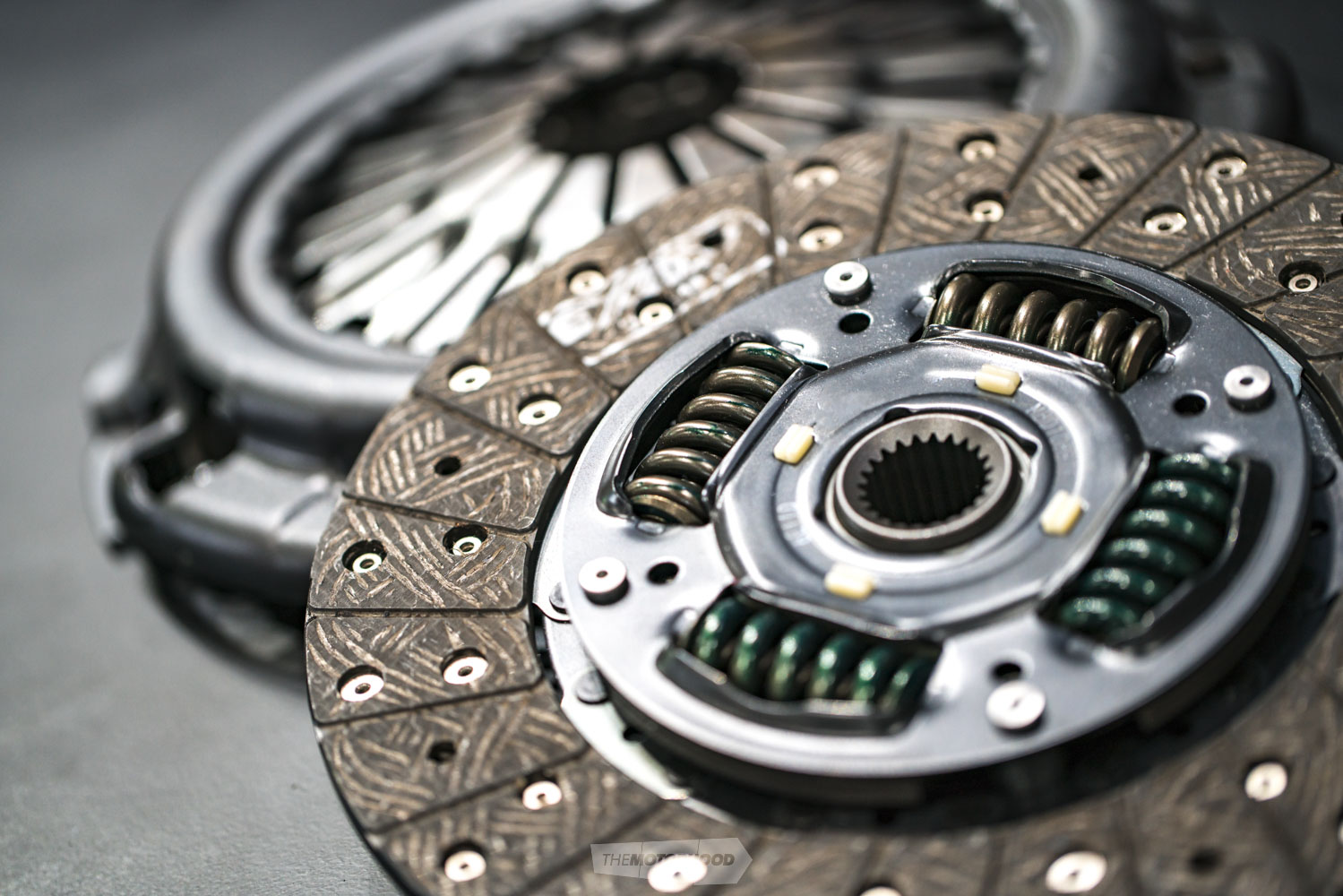

Most cars will get through more than one clutch in their lifetime. Cars from the 1950s to the ’70s could get 80,000 to 120,000km — less if driven aggressively. Most of us have already experienced clutch slip, a lack of drive, seen the rev-counter needle waver, or heard the engine revs wander — unmistakable signs that the clutch is on its way out. Sometimes, slip caused by clutch-plate wear can be adjusted out. Some have automatic adjustment. “But we don’t like them,” says Ian Sole of Waikato Clutch and Brake Specialists. “They are complicated and collect dirt, which can interfere with their operation.”

Most cars are engineered to make replacing clutches relatively straightforward. If you are going to do this yourself, make sure you check out the clutch release bearing too, which moves the pressure plate. Ian’s company has spent 30 years reconditioning clutches. Workshops send them the clutch plate, along with the flywheel, pressure plate, and clutch release bearing, as they can all suffer wear.

Sometimes, a failing clutch will cause other damage. The rivets in the clutch plate can score the flywheel or even cause damage in the gearbox. Ian says that flywheels always get machined for new clutches these days to ensure quality, and that almost all cars have hydraulic clutches today, although cable clutches were more common on older cars.

Most manual clutches have a single dished diaphragm spring — the fingers you can see on the pressure plate. The clutch release bearing flattens them, which takes the pressure off the clutch plate. An alternative design is a lever-type clutch, which has several coil springs inside it pressing the plate home. If the springs lose their strength, they can cause uneven wear or juddering. Ian says that they usually replace them with heavier springs, which gives a better clutch action.

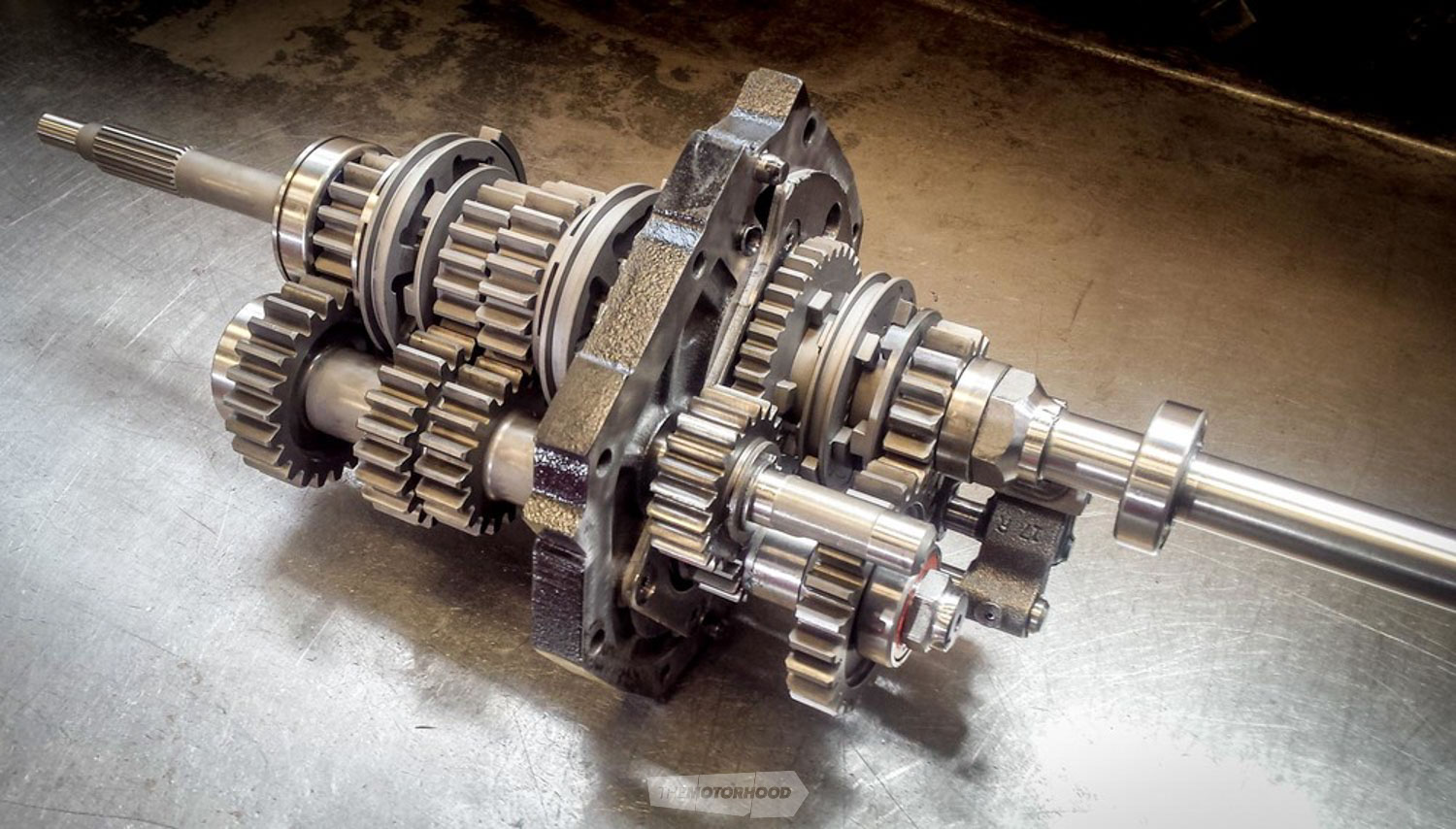

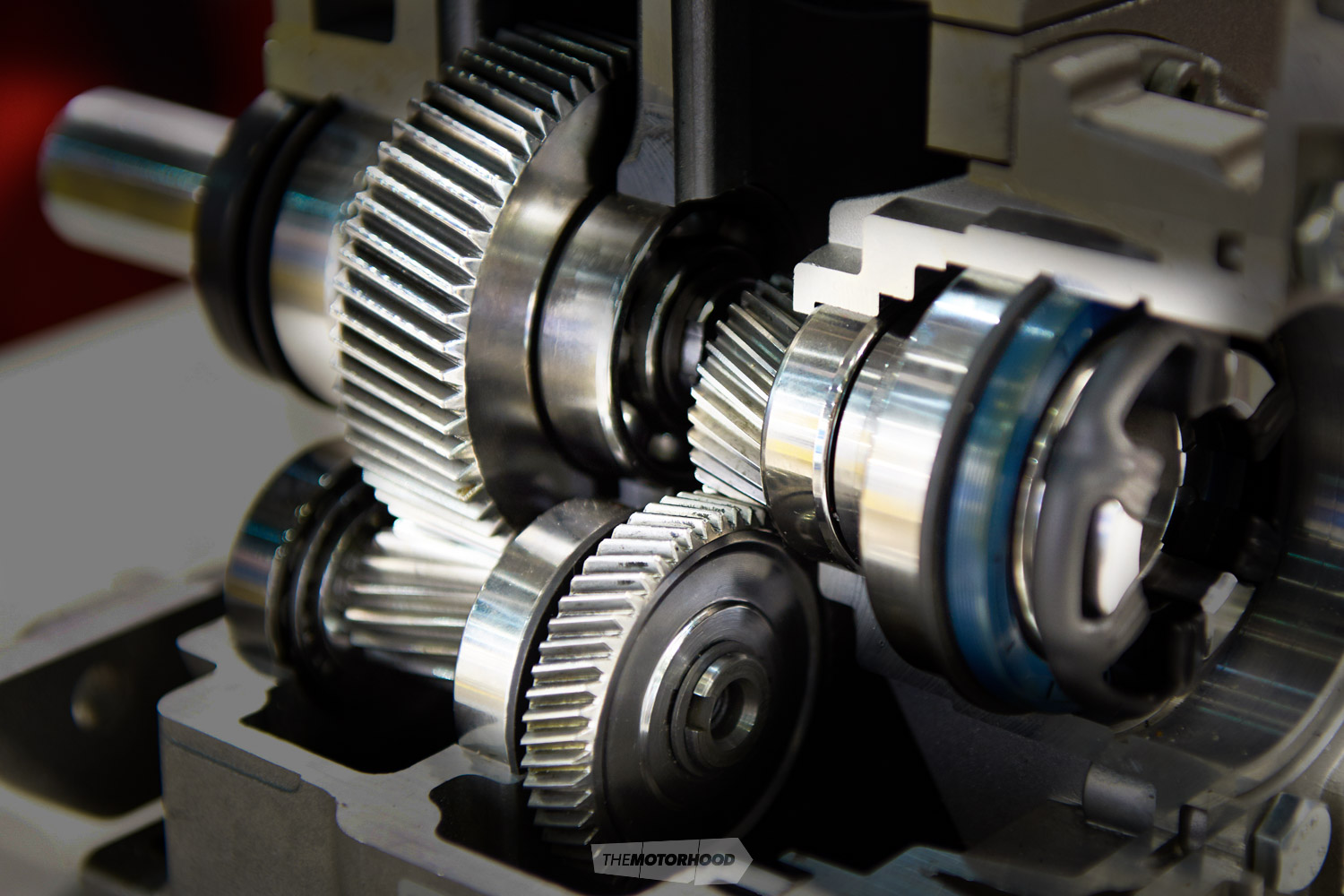

The next most common issue in the drivetrain is a weak synchromesh, often on second gear, which gets used a lot in enthusiastic driving. Look out for a weak synchro in older manuals offered for sale. Most owners would prefer to give someone else the pleasure of reconditioning a gearbox — and the expense.

‘Synchromesh’ is a combination of cones and grooved brass rings that cup together and help match the speed of gears before they engage. Replacing them involves dismantling the gearbox. If you are going to do that, it’s worth replacing oil seals and bearings, which means a full reconditioning is the best way to go.

Marshall Transmissions’ Liam Bright advises people to check upshifts as well as downshifts in a manual gearbox; make sure there’s no blocking or grating, and that the clutch doesn’t engage too near the top or bottom of its travel. He says that sometimes people change gearboxes but don’t set up the right free play in cable-operated clutches. Worn seals in a hydraulic clutch can also cause drag. He says that it’s surprising how quickly clutch drag can ruin first and reverse gears.

“Also check that the gear-lever action is positive,” he says. Selector cables in Mark I Cortinas, for example, can stretch, and worn bushes will mean the selector mechanism in the gearbox won’t engage the gears fully, leading to gear damage.

“If it’s popping out of gear due to floppy bushes and you change the bushes, it could still pop out of gear due to uneven wear”

Liam has another great tip for anyone wanting to fit a different gearbox — make sure that there’s a good supply of parts for it first.

So what about parts for your 1939 Vauxhall 14-6? The internet is a real boon to finding parts from trusted sources locally or overseas. If that draws a blank, you can get virtually any gear you need repaired or made in New Zealand, but it’s not a cheap exercise.

Wellington Automotive Gearbox Specialists (Wags) specializes in manual gearboxes. Dave Jensen says that classic cars with tired boxes are just part of Wags’ business. They also change diff ratios for customers wanting quieter or more economical cruising. But a large part of the company’s work is building gearboxes and driveshafts for performance, race, and drift cars. Wags brings in and installs specialist gear sets from overseas.

“They are supposed to drop straight in — and some of them actually do,” he says. But Wags also designs and manufactures its own gears. The team is currently building a one-off gearbox for a 1930s Hispano-Suiza, replacing its crash gearbox with the company’s own dog-engagement system. They also carry out ‘isotropic superfinishing’ on gearbox and diff gears, which reduces noise, friction, and operating temperatures, and reduces bedding-in on crown-wheel-and-pinion sets. Dave has found that it extends component life and it’s valuable for vintage or classic cars when you want to make everything last as long as possible.

Wags’ work extends into sourcing or fabricating anything and everything from custom looms to roll cages. “No one in this workshop is allowed to say it can’t be done,” says Dave.

Or you could consider an upgrade, installing a later gearbox with the advantage of a fifth gear, especially if replacement part prices put this in the frame.

Most Rover P6s, for example, came out as automatics, but owners preferring a manual pay a visit to Waikato’s Conversion Components

The company supplies conversion kits, including new bell housings, clutches, a gearbox if needed, gear linkages, and pedal boxes for some cars, when original parts are in short supply, for a broad range of classics.

Proprietor Colin Dray supplies reconditioned Toyota gearboxes — because they just work, “and work very well,” says Colin.

He says, as a rule, most cars are too low-geared. British cars in particular have a low second gear and a high third gear. “It’s not until you go to England that you understand why,” he says. “First was for hill starts, so you could start in second most of the time, and the long third gear could dispose of what they call hills over there.” The Toyota Supra boxes that he imports provide proper gearing.

Colin also says that most older cars had overly heavy flywheels. Lightening them eases the burden on the clutch. He even manufactures new flywheels for Aston Martins going the manual route.

Converting to a manual gearbox will also mean paying attention to the driveshaft, as the clutch and gearbox assembly will be a different length. Usually, they can be cut but sometimes they need to be longer, so they are retubed. “And they need rebalancing,” says Colin.

Automatics are classics too

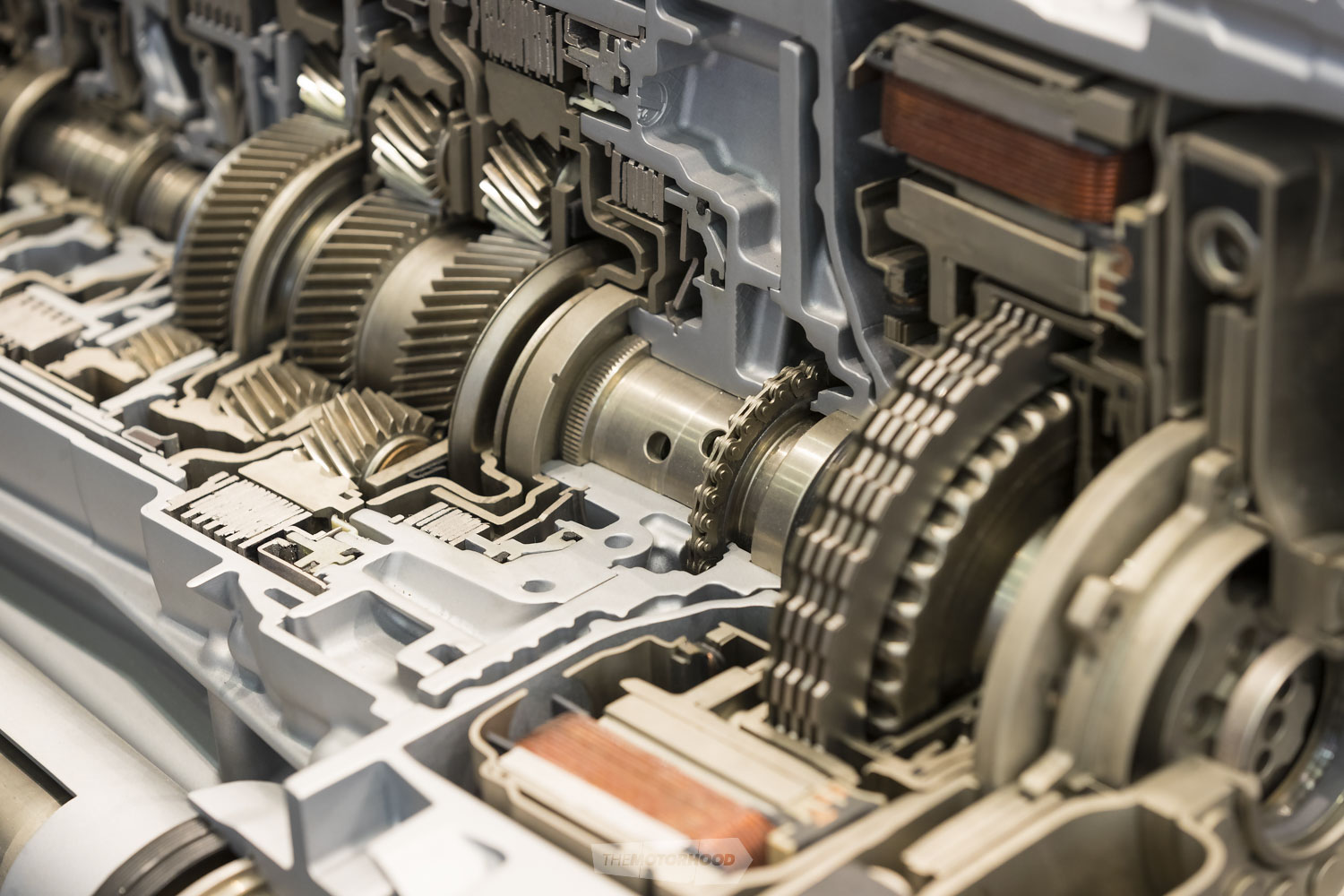

Automatic gearboxes operate quite differently — check out the animations for automatic gearboxes online, which show the mind-bendingly clever orchestrated dance of planetary gears and how different final-drive ratios and even a reverse gear are obtained just by shifting the connections between three main elements — the outer ring, the central shaft with its fixed ‘sun’ gear, and the carriers holding the planetary gears.

The part that gives them the derogatory nickname of ‘slushmatic’ is the torque converter, which, for autos, replaces the clutch in front of a manual gearbox. A ‘torque converter’ is a fluid coupling that disengages drive at low engine speeds, but, instead of the oil coming off the turbine splashing down onto the impeller, it has a stator plate that redirects returning oil to the impeller, aiding its spin and multiplying the torque.

Tony Klay and his staff have been working on automatic transmissions for 30-plus years at Ōtāhuhu Automatic Transmission. Tony cautions against ignoring oil leaks, slipping, or clunky shifts; often indications of a pending failure.

He says that classic cars often suffer oil leaks because they spend more time sitting around. Oil drains off the torque converter and ‘overfills’ the pan when the vehicle is not in use, meaning that seals and gaskets are sitting in oil and can start weeping. That’s why you generally check automatic-transmission fluid levels with the engine running (consult your owner’s manual to be sure), when oil is in circulation through the torque converter.

This can sometimes cause the transmission to ‘burp’ oil out of the breather on start-up, as the air is displaced, often leaving a dinner-plate-sized pool of oil on the floor. “I just urge people to check their fluid before they go on a run. It can save a lot of grief,” says Tony. He also says that oil seals are generally the first to go.

Dustin Phillips of Hamilton’s Marshall Transmissions says that internal clutch linings can also absorb moisture and break down after a long period of disuse. Seals, bushes, and clutch plates within the transmission are routinely changed in a rebuild, but it might not stop there. He says that US boxes may have done hundreds of thousands of kilometres, so bushes and planetary gears can also be worn out. He says that automatic-box overhauls can cost as little as $1800 but can rise to $10K for modern gearboxes with complex valve bodies that have to be replaced as a unit. Everything else gets a careful inspection for wear. Tony says Ōtāhuhu Automatic Transmission uses only OEM parts to ensure the longevity of rebuilds

North Shore Automatics ([email protected]) also knows that era, along with the more modern performance boxes. Experience with their Formula 5000 race car also taught them about the Hewland transaxles beloved by vintage and classic racers.

Shayne and Fraser Windelburn’s father started the business when the classics of today were new, in the mid ’60s. Shayne prefers working on the older automatics — “anything without a solenoid” — as the electronic controls on modern gearboxes mean that you also need a good auto-electrician on the job. The good news for classic car drivers is that older boxes are simpler and cheaper to work on. It’s also possible to beef up older transmissions, adding extra internal clutch plates, for example.

Given all the team’s experience, staff know what to look for in older transmissions. BorgWarner boxes, for example, will often suffer a broken diaphragm spring. Shayne also recalls attending a conference in Australia at which one attendee stood up to thank General Motors for inventing the Trimatic, famed for losing its reverse-gear clutch lining. “ ‘Without them, none of us would be here,’ he said.”

Eric Prain of Automan Automatics (i[email protected]) in Christchurch says oil leaks, slipping, and delays prompt most visits to his Yaldhurst shop but occasionally it’s because something goes bang. He knows what to look for but still sees things he hasn’t seen in his previous 35 years on the job “How did that happen?”

He also prefers to work on classics for several reasons. The hardware is pretty sturdy, unlike modern boxes which are built lighter and lighter to improve efficiency, they are less complex and classic owners understand the the need to do a thorough job. He says they are also much nicer to deal with than someone who feels aggrieved the modern car they have spent a fortune on has just failed.

Making the differential

Differentials have two jobs. First, turning the power from the driveshaft through 90 degrees to each of the rear wheels. This needs a direct coupling. That’s fine when the vehicle is going straight ahead, but as soon as the car goes around a corner, one wheel scribes a wider arc and therefore wants to go faster than the other. The differential takes the torque from the engine and apportions it through clever gearing so that all three shafts can turn at different speeds.

If you’re going to be driving a lot on low-grip surfaces, or you provide an excess of power in hard-charging mode, you need a limited slip differential (LSD).

Most of them incorporate clutch arrangements, both wet and dry, to engage the slow wheel although a couple of manufacturers acheived the same goal with sensors on the driven wheels, simply applying the brake to a spinning wheel. The oil in a standard diff will often last a lifetime but an LSD can need oil changes, depending on the type.

Torson differentials — several different designs — simply use an incredibly clever arrangement of gears to redistribute torque.

Most of the time, a whining diff needs a new crown wheel and pinion. Changing the gearing to get a more economical cruise is relatively easy with Toyotas, Holdens, and Fords, as a good range of different ratios is available. Three-speed auto Holdens can also use three-speed manual ratios to get a better spread of gears. Otherwise, aftermarket parts have to be looked at. Gearbox and diff specialists recommend running a new diff in for 1000km before pushing it hard, as the metal needs to run through a few normal heat cycles and bed-in properly.

Making a niche in gears

Christchurch’s Duralloy Gears has specialized in making gears for most of its 60-plus years in the business. Car gearboxes are now just a small part of the business, which includes gears for aircraft, log haulers, ski lifts, fishing-boat winches, cranes, and industrial machinery — but no job is too big or small.

Duralloy’s Hayden Neil says that they can repair single teeth using TIG welding but won’t repair gears with three teeth missing. “It won’t be long before the rest go,” he suggests.

“It’s an intricate process,” he says, involving machining a blank, hardening it with heat treatment, relieving the pressure, then re-profiling the teeth, as the heat treatment can distort them.

The team works with three different types of steel, but if the customer leaves the choice to Duralloy, E110 steel is chosen “every time, 100 per cent”, as it requires less stress relief and is more durable. That means customers will get more life, even from parts that commonly fail. Duralloy has made parts for Ferraris and Jaguars, and the company also has Mini and MG gear sets in stock as they are popular items, as are crown wheels and pinions for Model T Fords.

This article originally appeared in New Zealand Classic Car issue 336 — you can purchase a print copy by clicking the cover below