data-animation-override>

“Denny Hulme was the oldest of the ‘trio at the top’, but the last to make his Formula 1 debut — that came 50 years ago at Monaco”

When Denny Hulme was named to drive in the French Grand Prix on June 27, 1965, it was the first time that Bruce McLaren, Chris Amon, and Denny had ever appeared together in a Formula 1 Grand Prix. Bruce did all 10 GPs that year, as Cooper’s team leader in what would be his final season for the only team he’d raced for in Formula 1. Chris, however, only appeared in two GPs in 1965, and so there was a serendipitous aspect to the fact that one of them should coincide with one of Denny’s appearances.

Since the start of the world championship in 1950 the French Grand Prix had alternated between Rouen and Reims, but for 1965 the race was awarded to Clermont-Ferrand — with 8.055 kilometres of turbulent downhill sweeps and 51 bends undulating and winding their way around the Puy de Charade, an extinct volcano. Opened in 1958, the challenging circuit resembled a roller coaster, and caused more than one driver to experience nausea.

In 1964 a Formula 2 race had been held there, and included in the entry were two of the brightest young prospects of the day — Jackie Stewart and Jochen Rindt, who finished second and third respectively, behind Denny. It was the rugged Kiwi’s first win in Formula 2, and, on a track that sorted men from boys, he very much announced his arrival with a clear victory from pole position.

Half a century ago Denny’s boss, Jack Brabham, elected to sit out the race and thus opened the way for the Kiwi’s F1 debut — and it looked a typically canny decision when Denny emerged quickest of all after the first session. This was 1965, very much the year of Jim Clark, and that year’s normal order of things resumed after qualifying with the Scot on pole, but Denny was quickest of the Kiwis in sixth from Chris who was starting in eighth, just ahead of Bruce.

Clark won, in his final race with the Lotus 25, from Stewart’s BRM and the Ferrari of John Surtees, but Denny served notice of what he was capable of at the highest echelon with a fine fourth place finish on debut.

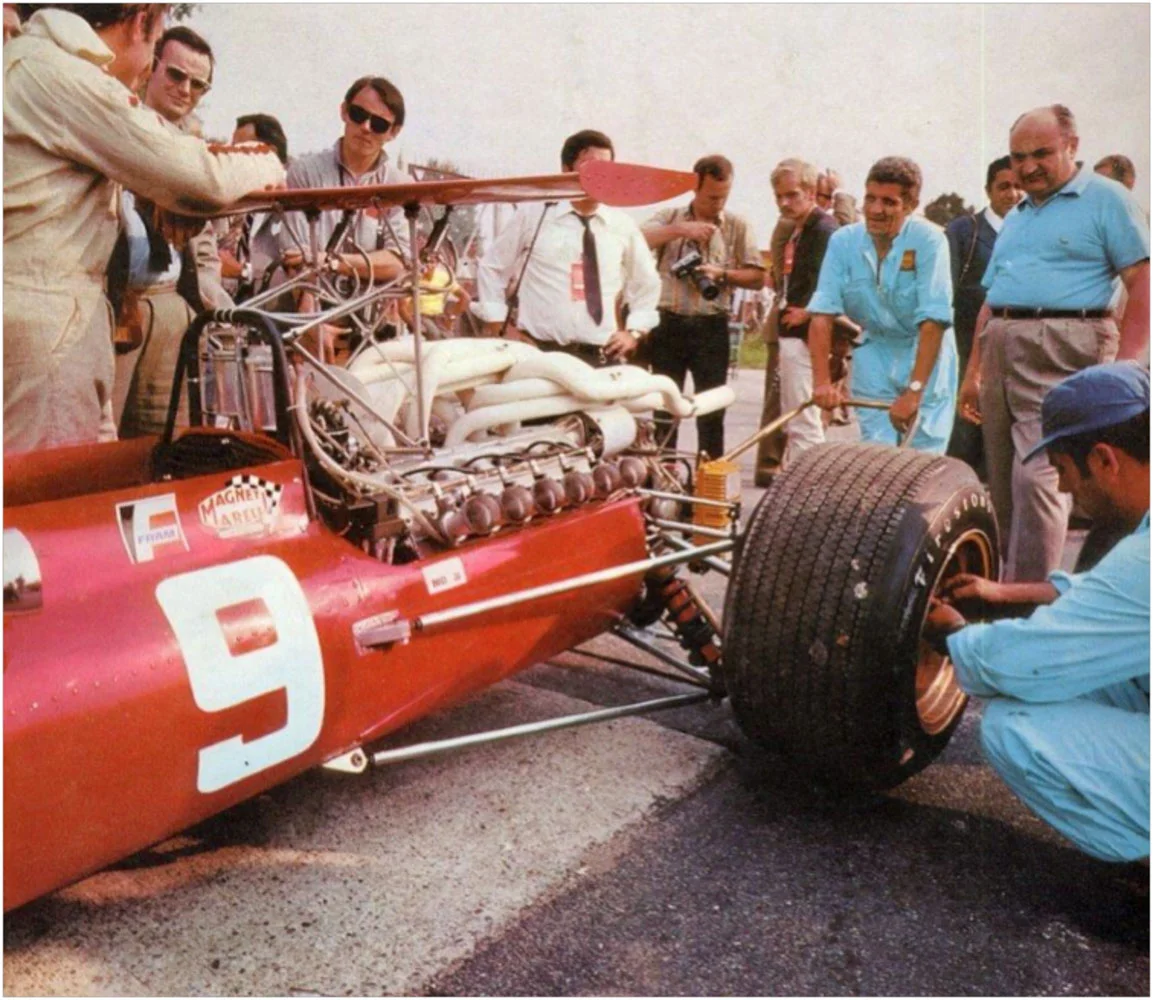

Chris Amon and Ferrari’s flat 12

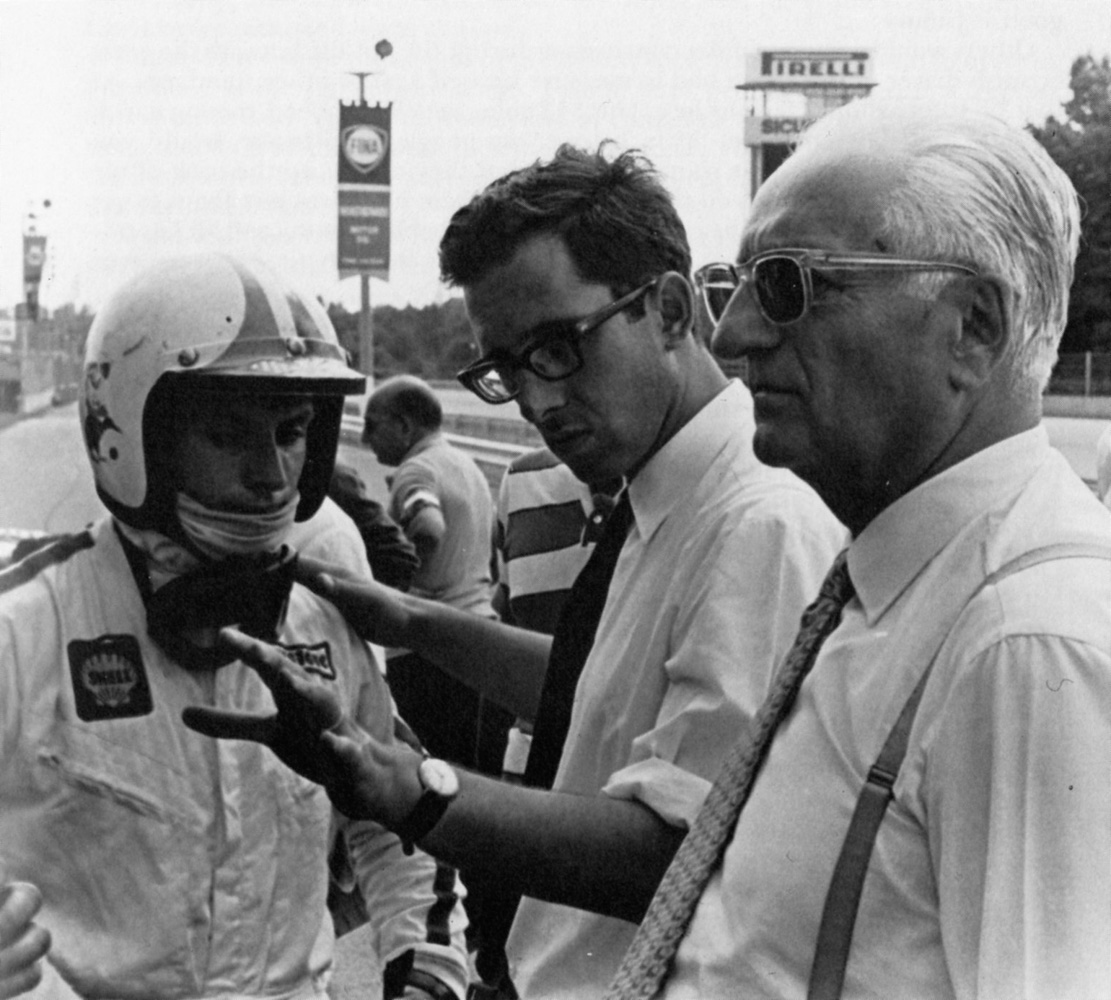

Speaking of Chris Amon, a number of people have clearly been thinking the same thing in light of the 2015 Formula 1 world championship — has Fernando Alonso done what our Ferrari driver did in 1969, and leave the Scuderia with time left on the contract?

After five seasons comprising a mixture of ecstasy, promise, hope, frustration, and despair, Spain’s best-ever racing driver split with motor racing’s most famous team, and headed for the latest version of McLaren-Honda, which so far has been a far cry from the last time those two famous names combined in 1988. However, despite what Alonso went through between 2010 and 2014, at least there were victories, and even a chance of taking the title.

Chris too had victories, but they came in the Tasman Series and in sports cars — including at his Ferrari debut in the Daytona 24 hours. In Formula 1 there was little to smile about. In contrast with the seminal ‘shark nose’ Ferrari of 1961, with which Phil Hill and Wolfgang von Trips fought out the world title, the F1 Ferraris during the Amon era had, as he recalls, “wonderful chassis, fantastic noise, no power.”

The Ford-funded Cosworth DFV arrived on the scene in 1967 for the exclusive use of Lotus, but by 1969 it was widely available — by then this compact, light, powerful and reliable jewel had already started rewriting history. In fact, it was everything the V12 Ferrari wasn’t.

Mind you, Enzo’s famous scuderia weren’t exactly standing still, and by mid 1969 Chris was testing the new flat 12, but after another failure his mind was made up — he had to have a Cosworth, and signed for March. The flat 12 came right at about the time the March reached the end of its short development phase. As Chris would later recall, “to make matters worse, Ferrari really came good. It was like I got a double dose.”

Ferrari won four of the final five races of 1970 — a works March never won a full Formula 1 Grand Prix.

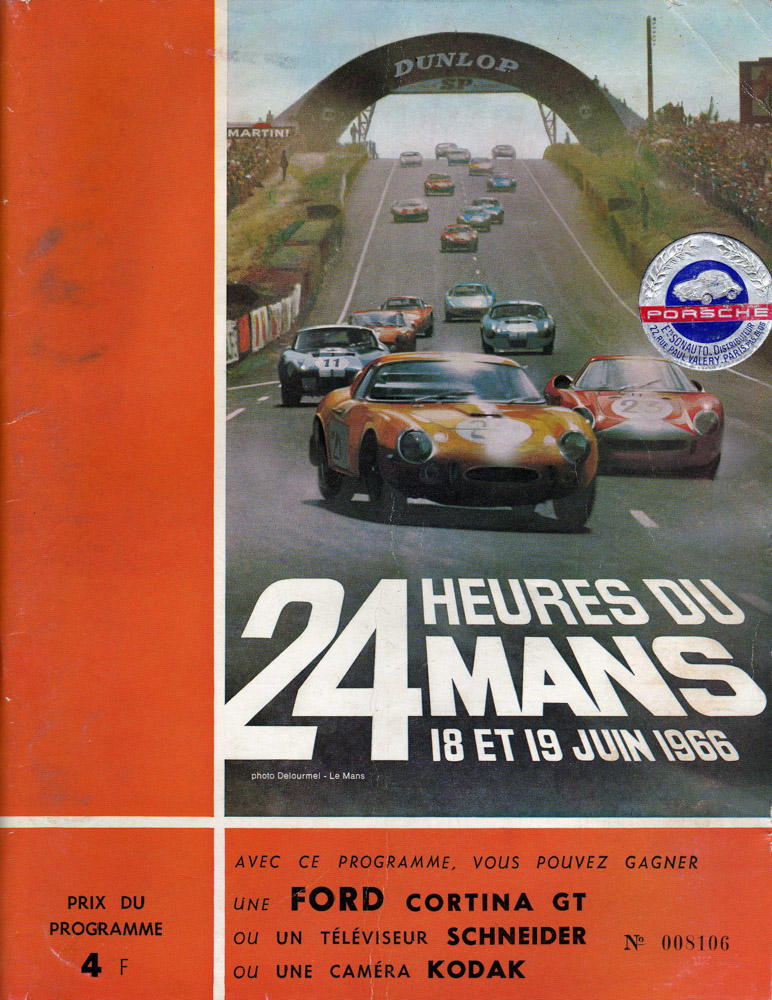

Endurance racing

June is Le Mans month, and 2015 marks half a century since a Ferrari last won the French classic. There had been a time, in the early ’60s in particular, when the scarlet cars were unbeatable — winning the lot and capping it off with the first six positions in 1963. To be fair they were somewhat unchallenged until the might of the Ford Motor Company turned up. Peeved at Enzo Ferrari’s decision not to sell when the Detroit giant believed it had a deal, the ‘blue oval’ set out to beat the Italian marque at the 24 Hours of Le Mans. This quest led to the Ford GT40, a most worthy by-product, and after determining that a 4.7-litre V8 wouldn’t be enough to beat the race-bred Italian 3.3-litre V12s, Ford returned in 1965 with a pair of 7.0-litre versions. There were Kiwis in both — McLaren shared one with Ken Miles, with Amon/Phil Hill in the other. The Kiwis were both chosen to start.

“We were told to take it easy at the start because the gearbox was fragile, but later I was shown some photographs just after the start and here are these two black lines — so much for going easy — we were way, way quicker than anything,” Chris recalled.

Neither big Ford finished, and nor did any of three works Ferraris, but it was still a one-two-three for the products of Maranello, with victory to arguably the most unlikely duo ever to win the 24 Heures du Mans. The winning car was the private NART (North American Racing Team) entry handled by a pair of out-and-out racers, neither of whom was noted for pacing themselves. Masten Gregory was a slow-talking Kansan who’d been at Cooper in Formula 1 with Brabham and McLaren in 1959. He was known for his spectacular crashes, including one in which he literally stepped from his car seconds before impact. He was teamed with 23-year-old Austrian acrobat Jochen Rindt, who drove as if tomorrow hadn’t yet been invented — but the pair won … or was it a pair?

In those days it was very much two to a car, not the three-driver arrangement that has been prevalent since the early ’80s, however, in more recent years the name Ed Hugus emerged as perhaps being the guy who anchored the early-morning stint of the winning Ferrari 275LM. The American was no rookie, having first started at La Sarthe in 1956, and in 1965 was down as a reserve driver, but no record of him competing ever existed.

Years later Hugus claimed he’d driven for two hours when the nominated drivers were exhausted. Had anyone noticed, the car would have been disqualified, so not surprisingly it was kept very quiet — assuming of course it happened.

Le Mans triple

And on the subject of Le Mans, 2015 marks 20 years since a remarkable triple was achieved — the only time it happened. Ferrari, of course, has won numerous Le Mans 24 hour races plus Formula 1 world championships, and Lotus won world championships and the Indianapolis 500, but only one manufacturer has won all three — McLaren.

The first of the three Indy 500 wins came in 1972, while the first world champion in a McLaren was Emerson Fittipaldi in 1974, but in 1995 their first mass production ‘supercar’ was being sized up as a potential Le Mans contender. At a time when the F1 team had just started its long partnership with Mercedes-Benz, the sports car — designated F1 GTR — was powered by German rival BMW’s 6.1-litre V12. Seven started and there were four in the top five — including the most important place. The winning drivers were France’s Yannick Dalmas, Masanori Sekiya from Japan, and the Finn JJ Lehto. In achieving the unique triple, they caused Mario Andretti to miss out on the only big prize in motor racing he hadn’t won. The 1978 world champion had won the Indy 500 in 1969 and the Daytona 500 in 1967, but Le Mans always eluded him — his Courage-Porsche was a lap behind the winning McLaren, and that’s the closest he ever got.

Lost and found

You never know what lurks in garages, workshops and sheds in New Zealand. Forty years ago Formula 5000 started showing the first signs of weakening in the three parts of the world where it was prevalent, and 1975, in fact, turned out to be the category’s penultimate year in the US, where it was launched in 1968, and also the final year it ran — on a standalone basis — in the UK.

In this part of the world, the last Tasman series for 5000s (or anything for that matter) was in 1975, although New Zealand and Australia had separate F5000 championships in 1976. The UK rules were relaxed in ’75, and in came a handful of cars powered by the 3.4-litre V6 ‘Cologne Capri’ engine. We’d seen, and heard, these gems in the Capris of Paul Fahey and Don Halliday, and although not as powerful as the ubiquitous small-block Chev, they were lighter and could be mated to a smaller chassis. If there had ever been any hopes of a Ford versus GM battle in F5000, then it was quickly quashed as the Chevs, and Repco V8s were soon dominant, despite the great success of Boss Mustangs in Trans-Am. Perhaps the Cosworth-built V6 could add some spice?

Future world champion Alan Jones drove a V6-powered March F1 car while Tom Walkinshaw also got his hands on one, but the ultimately the most successful of the Cosworth GAA–powered cars was the one-off Chevron B30 of Englishman David Purley. It was essentially a modified version of the Formula 2 car that Brian Redman raced against the F5000s here in 1976. Purley and the Chevron had two wins in 1975 and eventually finished fifth in the championship, but after a full winter rebuild and reconfiguration, it emerged as a much-modified weapon for 1976. The Brits continued to refer to the series as ‘F5000’ in 1976, but essentially it had become a high-level Formula Libre, with F1 and F2 cars mixing it with 5000s. The modified Chevron with the Cosworth V6 proved just the ticket, Purley was crowned champion, and with that the curtain came down on F5000 in Britain as well.

Who knew that car now resides in New Zealand? It is undergoing a full rebuild, and is scheduled to mix it with more conventional V8-powered 5000s at the 2016 NZ Festival of Motor Racing at Hampton Downs.

Bolton bolides

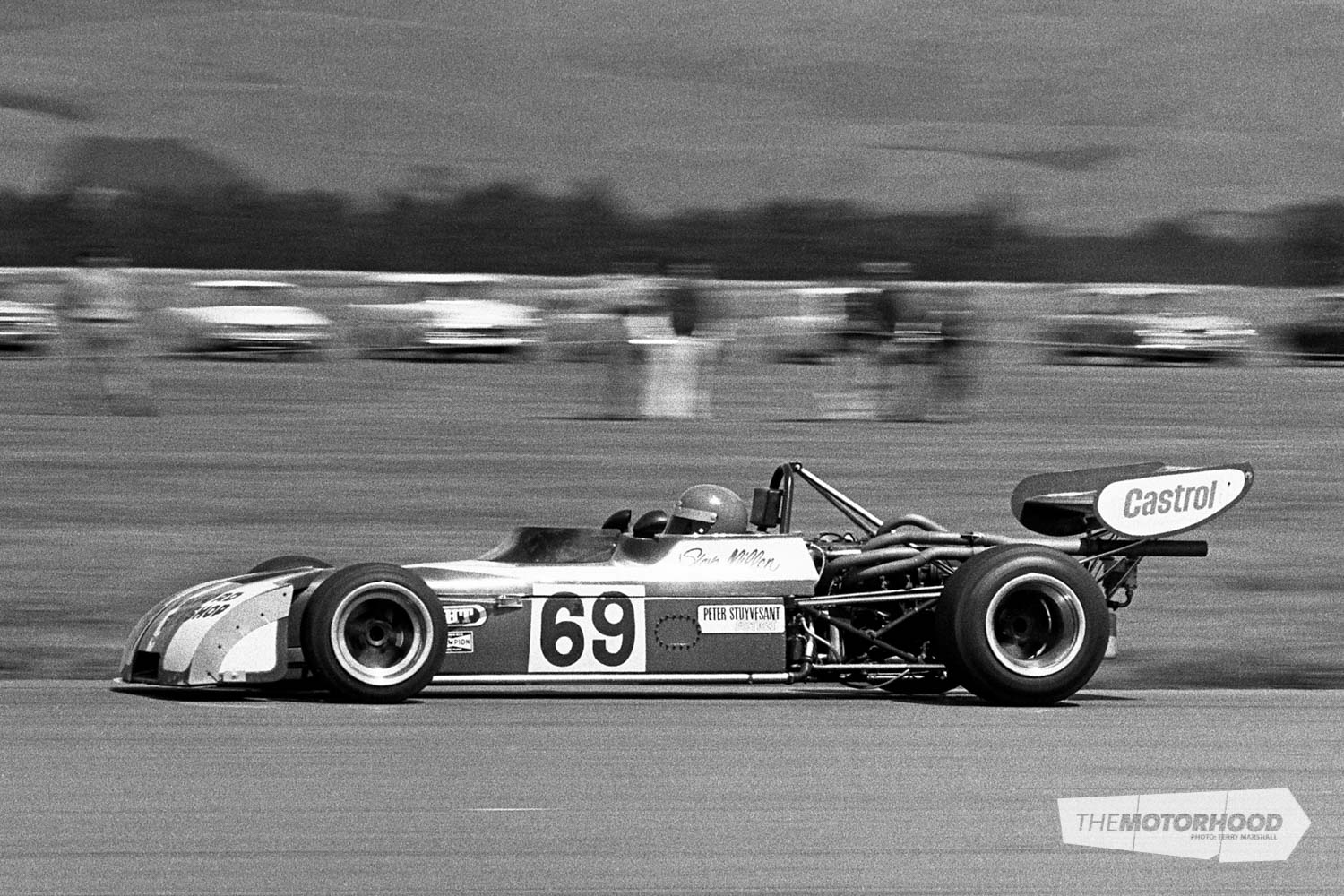

On the subject of Chevron, this year marks half a century since the Bolton-based marque first hit the track. The initial cars were ‘Clubman’ sports racers, and then came GT cars before the first open-wheeler (an F3) in 1967. Howden Ganley credits the B15 F3 car he raced in 1969 as triggering the turning point in his career. He later raced Chevron sports cars like the ones that sell for huge money these days compared with, say, an F2 car of the same vintage with an identical powerplant. The earliest-model Chevron we ever saw racing here in period was a 1972 Formula 2 B20 driven by Steve Millen. Peter Gethin won the 1974 Tasman Cup using a Chevron B24, while Keke Rosberg used Chevrons in 1977 and ’78 to take the first two Formula Pacific championships in New Zealand.

Chevron’s founder was Derek Bennett — a clever engineer and a good driver who was proudly Lancastrian. He was killed in a hang-gliding accident in March 1978, and having lost its spiritual leader, the company went into liquidation two years later.