Modest over-achiever

Jim Palmer’s name will be familiar to fans of local motorsports but, despite a stellar record, his name hasn’t transcended the sport in the way those of some of his rivals have.

But that won’t bother Jim

By Michael Clark

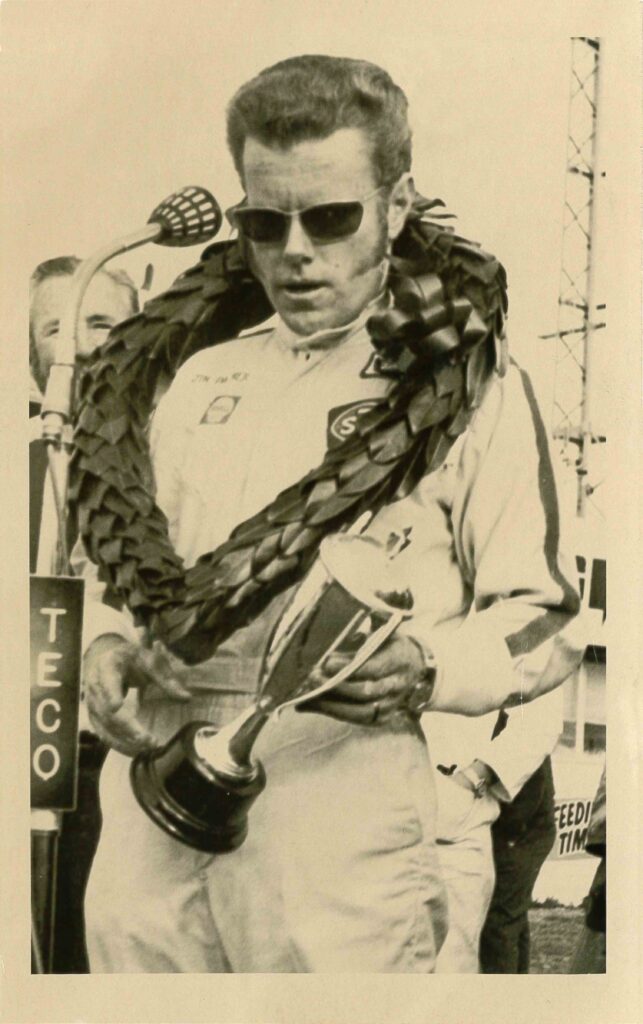

In the 1960s, Hamilton’s Jim Palmer won the prestigious ‘Gold Star’ four times and was the first resident New Zealander home in the New Zealand Grand Prix on five consecutive occasions. He shared the podium with Stirling Moss, Jack Brabham, Bruce McLaren, Graham Hill, Jim Clark, Denny Hulme, Jackie Stewart, and Chris Amon. The extent of his domination of the open-wheeler scene in New Zealand will probably never be matched or exceeded. Yet he’s always been modest about his achievements.

When I invite him to be my guest for a ‘Lunch with’ conversation, he suggests I consider someone more famous, adding, “It was all a long time ago”. I remind him of the time the two of us were wandering around the pit garages at Bathurst in 2017 and we bumped into Jim Richards. We recalled that JR had accompanied Rod Coppins to Bathurst in 1974 and, despite it being a first for both, they had ended up on the podium in third. JR listened as I related that this other Jim had finished second six years earlier in a Monaro and had once held the lap record around that daunting mountain circuit in a Brabham-Climax. JR was as impressed as JP was embarrassed. That’s typical Jimmy Palmer — quiet by nature. He’s never felt the need or desire to tell anyone what he achieved.

Driving sideways

I didn’t really want to re-stoke his embarrassment but I had to haul out that anecdote and remind him of JR’s reaction, and the confirmation it provided of his true status, before he relented. We met at the Palmers’ lovely property for a superb meal crafted by the always elegant Judy. We’ll start by discussing the early sports cars and open-wheelers and then next month, in part two, continue with the wide variety of touring cars Jim raced on both sides of the Tasman — and the success he enjoyed in those, too.

In January 2021, Jim celebrated his last birthday as a septuagenarian, which makes him younger than Graham McRae, Graeme Lawrence, and Kenny Smith, yet he’d retired from a long career while they were still on the way up. I knew that his dad was a racer and that Jim had started when he was 15 in a Buckler sports car that his dad had given up racing.

“It had a Ford flathead, and at Ardmore, the top speed was 80. Dad was probably keener than I was to start with. I was pretty lucky because most of the guys I was racing were twice my age.”

The records show that both speed and success came quickly. Jim acknowledges that “it all seemed to be quite natural to me”.

He’d started getting the feel of hanging the tail out with his schoolboy buddy.

“Howden [Ganley] and his brother Denis had mounted a 2hp Villiers stationary engine to a basic go-kart frame, and we’d take it to the yacht club. You could have walked faster than we were going, but at least we got the feel of a car sliding.”

Racing the world’s best

A Lotus 11 sports car followed, and as Jim’s experience and confidence increased, his performances really stood out, especially for a teenager. That was followed by another Lotus sports, the 15, before the Palmers took delivery of Jim’s first open-wheeler for 1960–61. Jim recalls the Formula Junior Lotus 18 only had a one-litre engine.

“But it was a good wee car and perfect for learning in.”

Then, as a 19-year-old veteran and continuing his dad’s policy of keeping their car as current as possible, the 18 was sold, and he got the first of two Lotus 20s.

“It had a 1.5-litre Ford Classic motor — so a lot more power.”

Jim was the first resident Kiwi at Teretonga, racing against McLaren, Moss, and Brabham, no less, in more powerful Climax-powered cars. They finished in that order, with young Jim fourth.

“Yeah, that was OK, but beating Pat Hoare’s Ferrari at Waimate a couple of weeks later was even better.”

It was the first of many Gold Star victories for Jim Palmer. He differentiates that car from its later sibling by colour. The new Lotus 20 that arrived for 1962–63 was orange and it was in that car that he expected to be racing at the first Grand Prix on the new circuit at Pukekohe. “We still had a 1.5-litre Ford but a few days before the race we were offered a Cooper-Climax that was a spare car for Reg Parnell’s team. It was a bit of a shock, as I recall. That 2.7-litre engine gave a lot more power but was not that much heavier than the Lotus. It was actually quite frightening.”

Jim needed no reminding that the race took place on his 21st birthday. He put in one of his trademark tidy drives and brought the car home third before returning to the Lotus for the South Island rounds. Prior to being reunited with the Cooper in Australia he was back at Waimate and concedes he won quite comfortably.

“I suppose I was getting used to the power of the Cooper by then so jumping back into the Lotus was a dream.”

Having adapted to horsepower so easily it was only natural to make the step up with the Palmers own car.

“I’m sure part of Reg’s thinking, when he offered us the Cooper, was that we might buy it.” Instead, they acquired the similar car that Angus Hyslop had just used to win the Gold Star.

“It was a bit lighter and it turned out pretty good.”

That’s Palmer’s modest way of recounting being the ‘first resident’ in the GP, Lady Wigram, and Teretonga, and winning the first of his four Gold Star titles.

It was much the same in 1965 with the Brabham BT7A except that he was tied for fourth in the Tasman Championship with Frank Gardner and 1961 world champion Phil Hill. Ahead of this trio were Jim Clark, Bruce McLaren, and Jack Brabham.

I have to ask — given that by then the year and a bit younger Chris Amon was carving a name for himself on the international stage — whether he ever thought of heading overseas.

“Not really. I suppose I was too much of a home boy. I liked Mum’s cooking too much! We were like the Lawrences and Smiths and Oxtons — we did it all as a family. Mum went everywhere, including when I tested the Ferrari in Italy — Enzo was there. That was the day Mum left the camera in the hotel.”

I ask if he ever lies awake at night and wonders what might have been.

“It never occurred to me at the time but I suppose it would have been nice to have had a go. Jimmy Clark would tell me to come to England ‘because you’re doing a good job’. That was nice, coming from him.”

Home and away

In a rare example of pushing the modesty envelope, Jim quietly adds, “I don’t think I’d have disgraced myself.”

Chris Amon was always adamant that Jim had the talent to do well in Europe. I also quizzed his old school and night-class buddy Howden Ganley on the matter.

“Absolutely; no question Jim would have done well. Look at how few crashes he had. It was one thing beating the best New Zealand had to offer at that time but he beat the resident Australians in Australia — and I bet they were revving their Climaxes harder than Jim ever did.”

Jim recalls the satisfaction of beating Frank Gardner, Spencer Martin, Kevin Bartlett, and co on their home tracks.

“It was one thing doing well against them here, but they had an advantage over there and they were who I was measuring myself against. Our equipment was about equal and I don’t remember getting well beaten very often.”

Next month we look at Jim’s most successful Tasman campaign, nearly landing a Ferrari, winning the world’s first open-wheeler title for McLaren, together with fun and games with tin-tops.

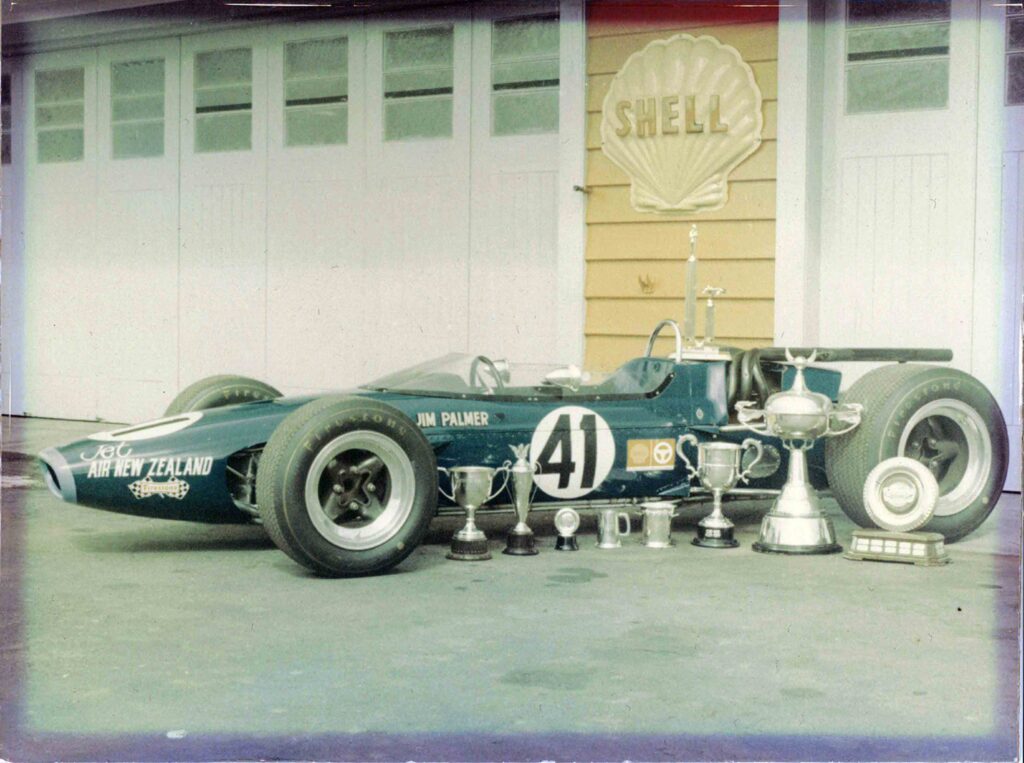

Jim’s favourite car

There is no doubt the car that Jim has the fondest memories of is the ex-Jim Clark Lotus 32B. “I sometimes wish we’d never sold that car. In fact, we had enough parts to build up another one … ” Other than adding his trademark ‘41’, he left the 1965 Tasman Championship–winning car unchanged, so it ran in works green and yellow colours. All New Zealand rounds of the ’66 Championship had been won by BRM, two going to Jackie Stewart who left for Australia with 24 points, ahead of his team-mate Dickie Attwood who had 15, one ahead of the leading Lotus-driven by a Jimmy — but it was Palmer, not Clark. Clark, the reigning world champion, had a mere six points to show for his month in New Zealand. The first of the Australian rounds was at Warwick Farm, as Jim recalls. “I liked that place, but some of the Kiwis never worked it out.” Despite qualifying seventh, Palmer soon had the BRM of Stewart behind him. “We had a great battle until my brake fluid boiled at about three-quarters distance. I kept thinking that orange nose is going to get me sooner or later — and he did.” Jim finished sixth while Clark finally won from Hill and Gardner.

Keeping cool

Even compared with the Australians, the Palmers were running on a tight budget. “We didn’t have money for spare motors, so we had to really watch the revs. Our tyres were ‘the best of the rest’. The bottom line was that we really needed to finish to earn the prize money to keep going.” And finish he did. When they arrived at the daunting Longford for the final round, the Palmers were chasing a 100 per cent finishing record but Jimmy was struggling on — of all places — the long straight. “It just kept weaving from side to side. I guess we were doing 170–175mph (275–280kph). I mentioned it to Clarkie who wondered if I was gripping the steering wheel too tight — remember, we had no seatbelts! He said ‘just relax’. I did — he was right. All these years on, I can still see those trees whistling past.” Jimmy qualified sixth. He was quickest of the locals and again faster than leading Australian Spencer Martin. “It was very hot. Late in the race, I was closing on Jack Brabham. Down the straight, he was running it in the shade of the trees to keep it cool. I thought I’d get him, but that Repco just had too much straight-line speed.”

Enzo observes

Nevertheless, the little Hamilton equipe came home fourth and, as only the best six scores counted — the fifth from Levin and sixth from Warwick Farm — points were dropped to give him 21 points for a clear fourth in the championship and, before the points were dropped, scoring only one behind the Team Lotus entry of Jimmy Clark.

It was a remarkable achievement and, despite his affection for that Lotus, its sale looked like opening an unimaginable opportunity. “Through Shell we got the chance to try out the Ferrari that (John) Surtees was supposed to have brought out the previous year. It was an ex-F1 car but with the 2.4-litre V6 — similar to the engine that Chris [Amon] had the next year. We got invited to Italy to test it.” His parents were, of course, with him. “It all went pretty well. Apparently, Enzo [Ferrari] was there. Not many Kiwis or Aussies that can say they test drove a Ferrari at Modena, their test track — which was a funny little wiggly place. The initial plan had been for us to buy it and although there was never ever any official reason as to why the car suddenly became unavailable, we were told by Shell — who were in the middle of it all — that Ferrari had just signed two new young drivers and they now needed the car for testing. Of course, one of those drivers was one C. Amon.” Had the drive come off, there would have been photographs aplenty, but the fact that his Mum left the camera in the hotel meant “I didn’t get any photos”.

Four Gold Stars

Instead, they bought another Brabham that Jim recalls was “a last minute acquisition. With a decent engine — like a Repco V8, that would have dropped in quite nicely — that could have been a good car.” However, the 1967 Tasman campaign, although poor by comparison to the previous few, still yielded trophies for the first Kiwi home in the Grand Prix and Teretonga International. After a hat-trick of Gold Stars, effectively the New Zealand open-wheeler championship, Jim lost out that year to “good old Roly” Levis and started thinking about what to do next. He headed back to Europe, initially thinking about the hybrid 2.1-litre McLaren-BRM that Bruce had used at the start of 1967 in F1. “But when that car burnt to the ground while testing, Bruce said that the F2 FVAs are going good, so we bought his M4A.” Jim didn’t know that the McLaren would be their last open-wheeler when he did the deal. 1968 was arguably the strongest field for any Tasman Championship with works cars from Lotus, Ferrari, and BRM. Unsurprisingly, points were hard to come by, and the seven Jim scored were from the New Zealand campaign only.

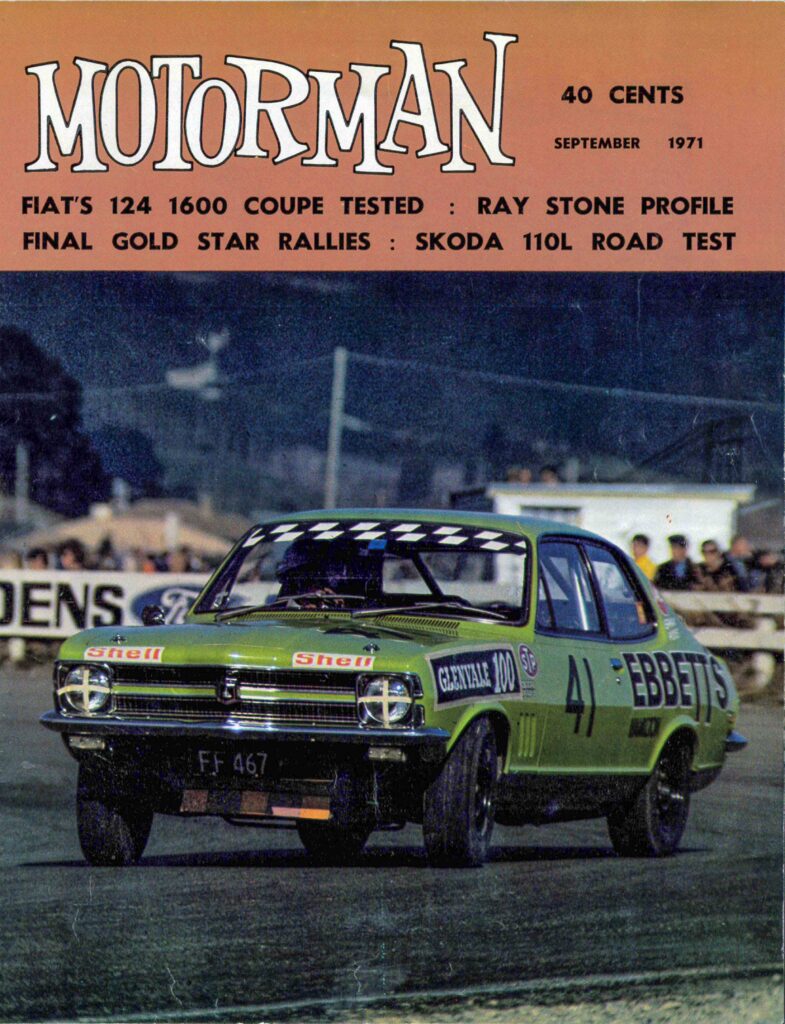

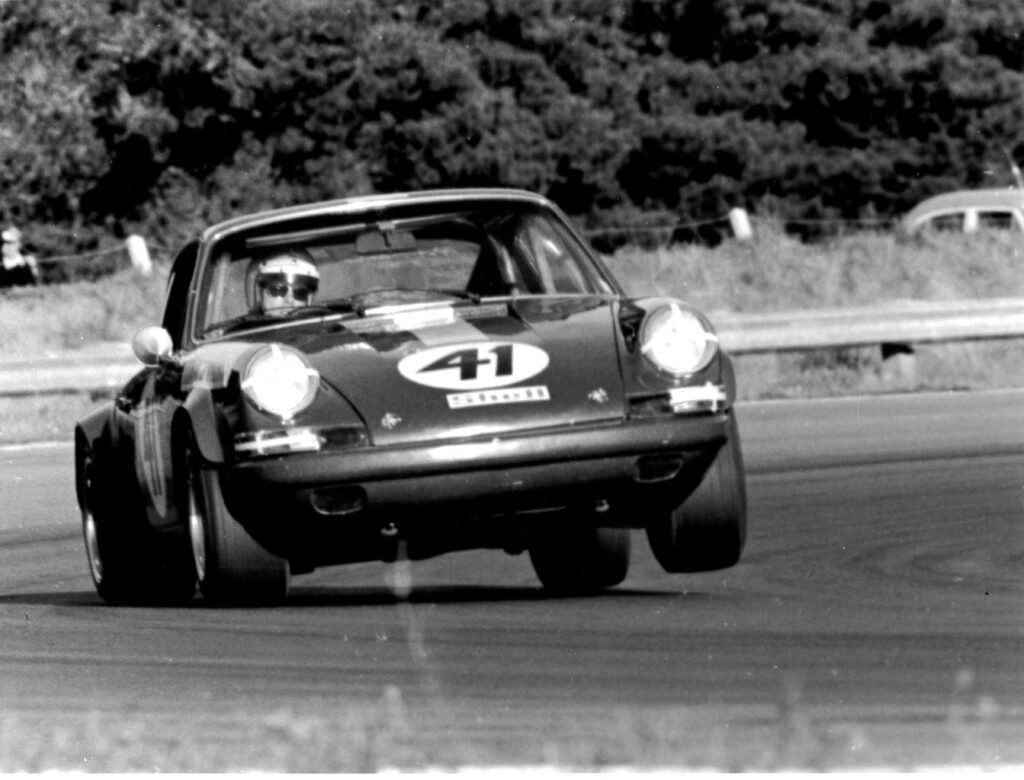

He won the Gold Star once again, completing his tally of four, and was the first local home in the two big races at Pukekohe and Wigram. “The car was sold to an Australian — but I’ve still got the original steering wheel!” A combination of skilled driving and first-class preparation resulted in the most dominant period at the upper end of New Zealand open-wheeler racing ever. Jim had always dabbled with saloons and had one of the lightweight Lotus-Cortinas, but after he’d finished with single-seaters he and his dad decided to “give saloons a real good bash. We got close to bringing in a Trans-Am Pontiac, but we bought the Porsche instead. As things turned out, we should have got the Firebird. ” Jim recalls his annual exploits in long-distance standard production races as “a bit of fun”, and when it came to sharing Paul Fahey’s Mustang he says “it didn’t take long to match his times”. Particularly special memories are reserved for the day he shared a Volvo with Colin Giltrap. “He could drive, and some laps, he’d be right on the pace.” Jim rounds off that sentence with a quiet chuckle for his long-time friend, who he still deals directly with today.

Bathurst glory denied?

I mentioned a day at Pukekohe when Jim in a yellow Monaro, had a superb wheel-to-wheel race with a red 3.8 Mark II Jag. In an instant, Jim is back there. “Tony Rolley— he was a good driver. Clean and very quick.” The photos bear out how closely they raced, and no one who witnessed Jim sawing away at the wheel at the big Holden could ever entertain the view that his talent was restricted to purebreds.

As we walked through the museum at Bathurst on the day after the big race in 2017, Jim started talking, quietly, of course, but we were left in no doubt that there were widespread concerns about the legality of the winning car. “But there was no way a team running a Monaro was going to protest another one also running one.” As it was, in his only ‘Great Race’ he finished second, becoming the first Kiwi on the Bathurst podium. “Although I don’t think there was much of a rostrum back then.” Typically, Jim can’t even acknowledge that without downplaying his achievement.

Mad men

As production car racing took hold here, Jim became a leading force, winning the Glenvale 100 at Bay Park twice. “Once in a Monaro and then in a 186 Torana XU-1. I raced a 202 as well, but the 186 was the better car.” It’s clear that he recalls them with fondness — which can’t be said for the Porsche. “911s ran with Escorts and Mustangs and Camaros in both England and Australia — we checked it out and got the green light before we bought it. We had some good dices, especially with Jim Richards and Paul (Fahey), but then we got told it was a sports car, not a touring car, and it would be banned.” For a man who has shunned controversy, Jim found himself in the middle of a contretemps with officialdom. “We didn’t want any part of that, so we sold the car, and I just stopped.”

As I have already mentioned, Jim is quick to downplay his accomplishments, but he raced for fifteen years, never had a major accident, racked up an enviable finishing record while consistently placing in the top tier of Kiwis amongst truly world class competition. And he did all of this driving cars that, considering all the fatalities they were involved in over that decade and a half worldwide, “sometimes [make you] think that a bloke’s got to be mad to have gone motor racing.”