In the decades after World War II, Chrysler attempted to bring the auto industry into the jet age, launching the most ambitious consumer test programme of all time — 55 cars, 203 families, and one hell of a tale

By Richard Truesdell

Chrysler’s Ghia-bodied Turbine Car, in its distinctive Turbine Bronze paint and black vinyl top, was a head-turner even before it fired up. To many, its exterior design language echoed that of Ford’s Thunderbird. This should come as no surprise given that both were guided by Elwood P Engel, who had moved from Dearborn to Highland Park in 1961 after having designed the 1961–1963 third-generation T-bird. It’s engine, however, was something else altogether.

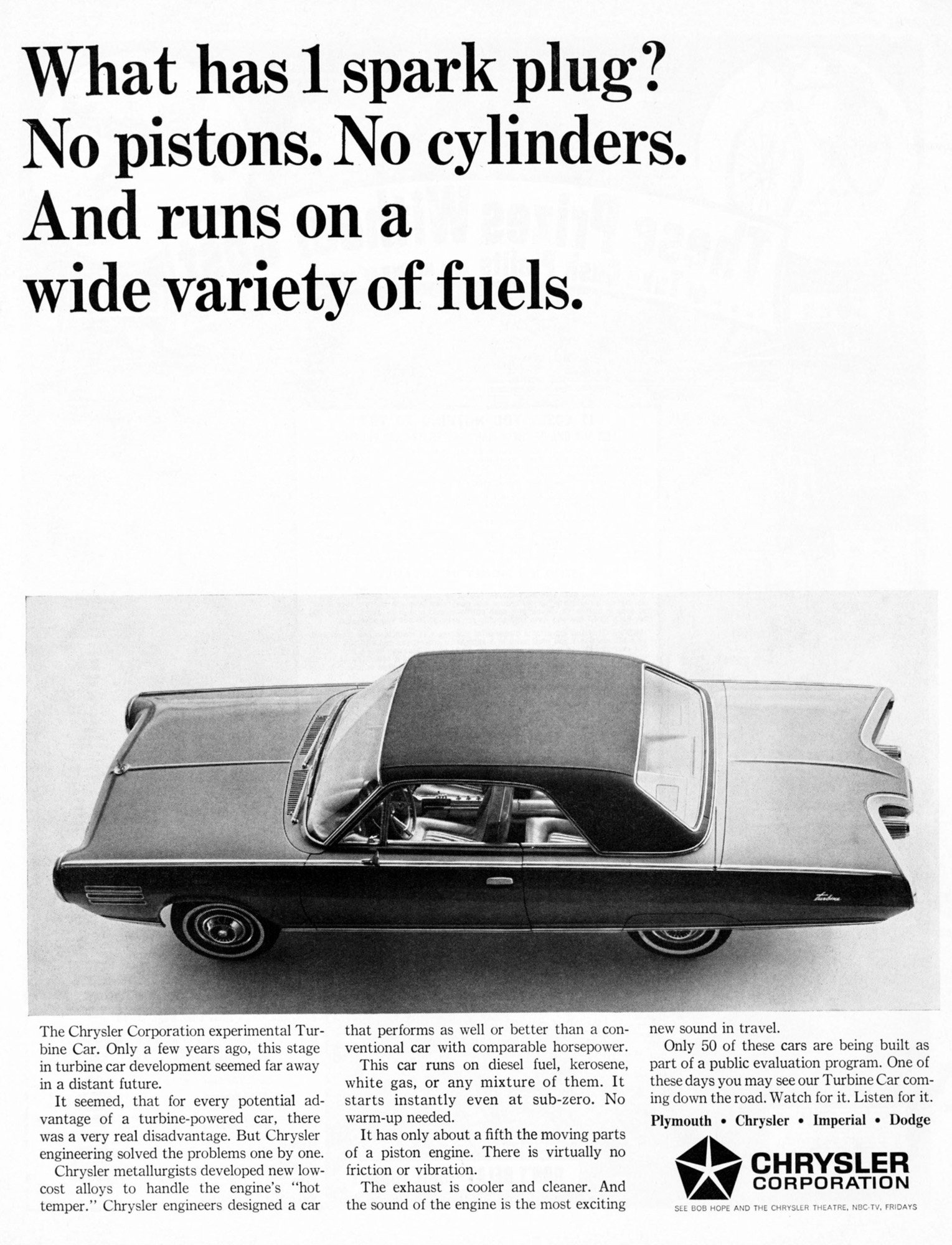

On 15 May 1962, Chrysler announced the limited production build of 55 gas turbine-powered cars. The cars would be lent to 203 drivers for three-month test drives over a period spanning more than two years. Only 46 cars actually went to the general public. Five were prototypes, two were held by Chrysler for marketing and dealer programmes while two were stars of the Chrysler pavilion at the 1964–65 New York World’s Fair.

According to Chrysler’s records, the first prototype was provided to Richard Viaha of Chicago, Illinois, on 29 October 1963, and the last was driven by Patricia Anderson, also of Chicago, who returned her Turbine Car to Chrysler on 28 January 1966.

Once selected, the individual was responsible only for gas and oil; everything else, including maintenance and insurance, was covered by Chrysler. The 203 drivers covered more than one million miles, with an average fleet fuel economy of around 13 miles per gallon —on par with contemporary mid-sized domestic two-door hardtops powered by a small block V8. In Chrysler’s case in 1963, that would have been a 318-cubic-inch V8-powered Dodge Dart or Plymouth Fury.

Chrysler’s consumer advertisements touted the low-maintenance aspect of a turbine car: it has only one spark plug, requires no antifreeze coolant, and can run on just about anything that burns, from low-octane jet fuel to distilled spirits.

To this day, the Chrysler Turbine Car consumer test drive remains one of the largest such programmes ever undertaken by an automotive manufacturer and yet, after more than a decade of development, it never resulted in a production car.

It has been estimated that it cost Chrysler US$50,000 to build each car owing in part to the expensive Ghia-sourced body. Inflation adjusted 60 years on to today’s prices that $50,000 becomes nearly $470,000 — and that doesn’t factor in the programme development costs spanning back to just after the end of World War II, when gas turbine engines were finding their way into America’s first jets.

First Generation (1954–1958)

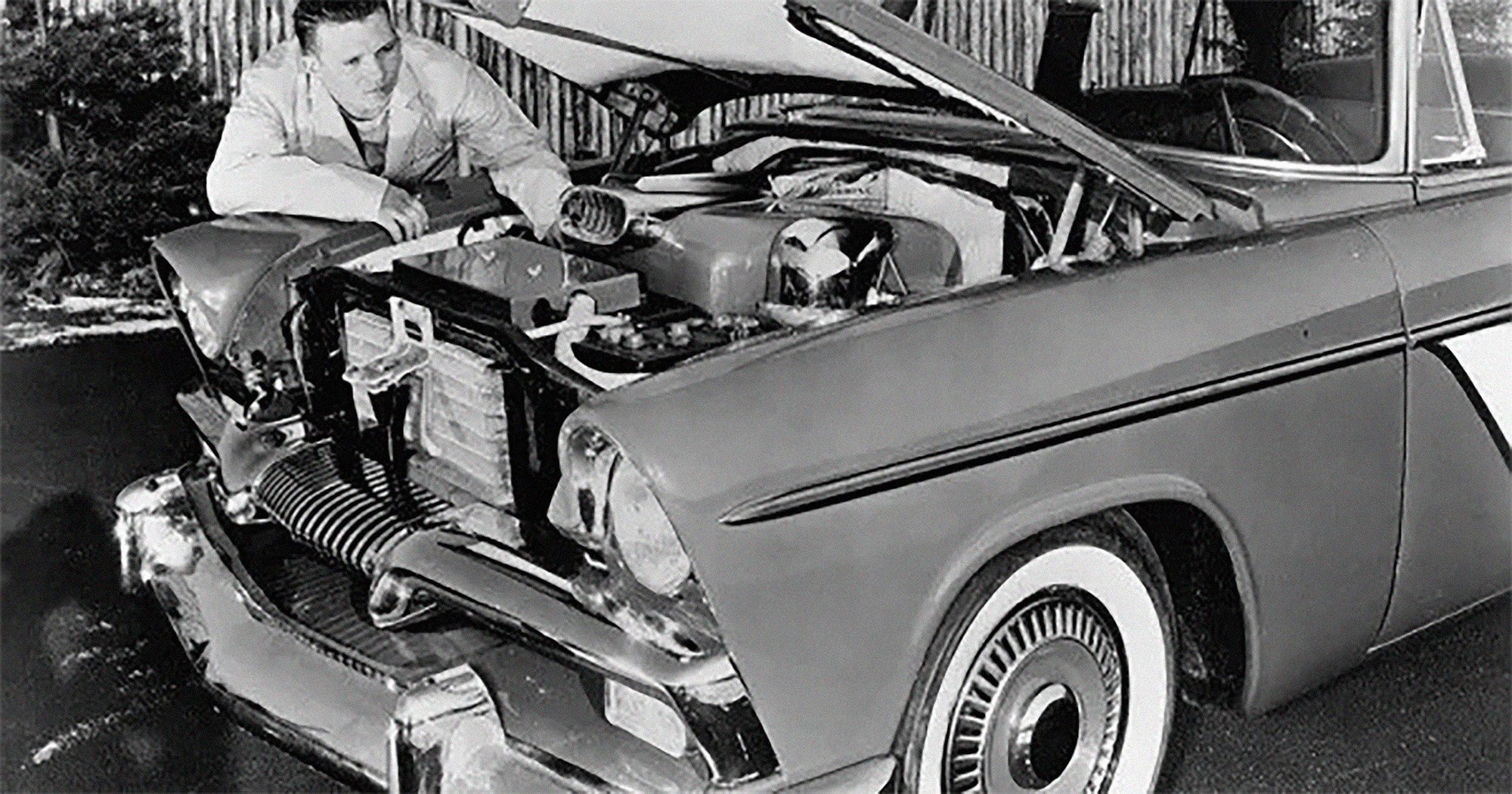

While the 1962–1966 Chrysler Ghia Turbine Cars are the best known of the programme, Chrysler installed prototype turbine car engines in a variety of Plymouth and Dodge vehicles starting in 1954. The first was a 1954 Plymouth Sport coupe, which sported a 100-horsepower gas turbine engine. It is credited with being the first automotive gas turbine engine that solved two of the engine’s most challenging problems — high fuel consumption and scorching exhaust gas. The development of a revolutionary heat exchanger — or, as it would become known, a regenerator — addressed both issues. It extracted heat from the exhaust gases and transferred this energy to air coming into the engine’s compressor. Chrysler touted the engines as capable of burning almost anything, and regular gasoline was not even the best choice. The high lead levels of lead in most mid ’50s blends were harmful to parts of the engine. Unleaded ‘white’ gasoline was a far better choice.

Second Generation (1958–1961)

The next generation engine appeared in late 1958, installed in a 1959 Plymouth two-door hardtop. It produced approximately 200 horsepower and was improved in almost every way, especially in fuel consumption. Chrysler’s engineers also made substantial improvements in turbine engine metallurgy finding lower-cost alternatives to the exotic materials usually used in jet engine combustion chamber liners, turbines, and blades.

Third Generation (1961–1963)

The next step forward was the CR2A third-generation engine which incorporated a major innovation: a variable nozzle mechanism acting as a shutter that provided engine braking. It improved efficiency and fuel economy while reducing the throttle lag that had plagued the programme from its inception.

The first car in the third-gen programme was the Turboflite concept car, exhibited at major auto shows in New York City, Chicago, London, and Paris in 1961. Trialled in various models, the CR2A was also installed in the 1962 Dodge Turbo Dart which made a four-day cross-country run in December 1961. Fuel economy was better than in the conventionally powered Dodge that made the trip in tandem with the Turbo Dart.

The Turbo Dart was joined by a 1962 Plymouth Turbo Fury, and together the twins toured major auto shows in more than 80 US cities.

Fourth Generation (1962–1966)

The famous Ghia-bodied Chrysler Turbine Car of the loaner programme was powered by Chrysler’s fourth-generation gas turbine engine. Producing 130 horsepower, it was the most efficient Chrysler gas turbine engine yet. Spinning at 44,500 revolutions per minute, this version could burn diesel fuel, unleaded gasoline — very limited availability back in 1963 — kerosene, JP-4 jet fuel, which was available at general aviation facilities, and even vegetable oil; the president of Mexico ran a Chrysler Turbine Car on tequila. Best of all, no adjustment was required when changing fuels.

The Turbine Car would sprint from zero to 60mph in 12 seconds, similar to a small block–powered (318ci) Dodge Dart or Plymouth Fury. While that doesn’t sound fast today, it was competitive with other similarly sized cars with small V8 engines.

The exhaust did not produce measurable carbon monoxide or raw hydrocarbons, but it did produce high levels of nitrogen oxide. This issue would bedevil the programme after increasingly stringent emission standards were introduced in the early 1970s.

At the end of the programme, all but five cars, which were donated to museums, were crushed. This was due to import duties that would have been assessed on their Italian-built Ghia bodies.

Fifth, Sixth, and Seventh Generation (1966–1979)

The Chrysler Turbine loaner-car programme — which was considered an unqualified success — persuaded Chrysler to continue gas turbine engine development. Next up was a turbine-powered concept car that was a precursor to the fastback, mid-sized 1966 Dodge Charger. A sixth-generation engine finally solved the nitrogen oxide issue and was installed in a 1966 Dodge Coronet.

A lighter, even more efficient, seventh-generation gas turbine engine was produced in the early 1970s, when Chrysler received a grant from the Environmental Protection Agency. The next application was to install an updated version into a specially bodied 1977 Chrysler LeBaron coupe.

However, by this time, Chrysler had become mired in a financial crisis requiring US government loan guarantees to avoid bankruptcy. One stipulation of the loan was to abandon its gas turbine engine programme, the thinking being that Chrysler needed to spend its resources on mainstream cars such as the ubiquitous K-car.

So Chrysler’s work with turbine engines never resulted in a true production gas turbine–powered car, but its legacy lives on. Defence contractor Honeywell continued the development of larger gas turbine engines. Its AGR1500 gas turbine engine was ultimately installed in the Abrams M1 battle tank. In the First Gulf War, the Abrams M1 battle tank was instrumental in the overwhelming defeat of the Iraqi Army in just 100 hours.

This article originally appeared in NZCC issue No. 377