The rewards of some restorations are more like those of an iron man endurance race, with emotional investment, self-reliance, and dogged determination being all that get owners to the blessed finish line

By Quinton Taylor, photography Adam Croy, Kerry Bowman, and archives

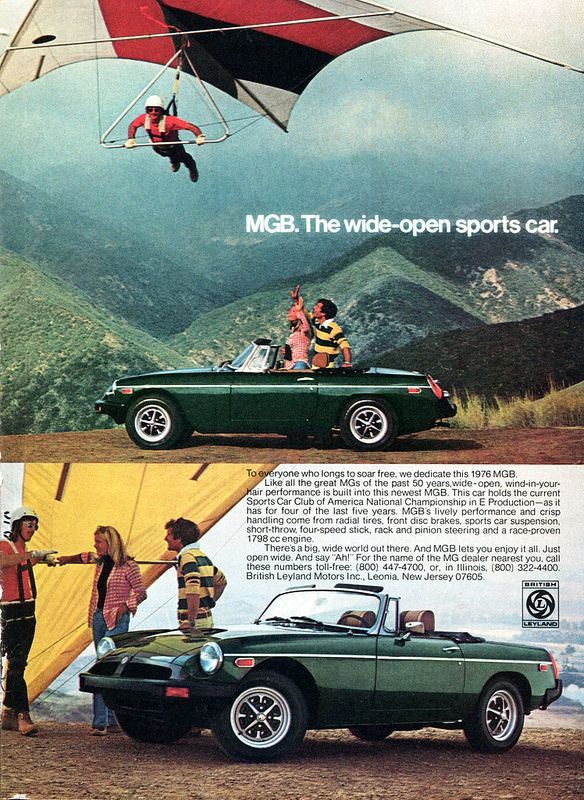

Introduced in 1962, the MGB was the embodiment of everything British in a sports car. An engaging drive, lightweight, and with sprightly handling, the ‘B’ was pure fun.

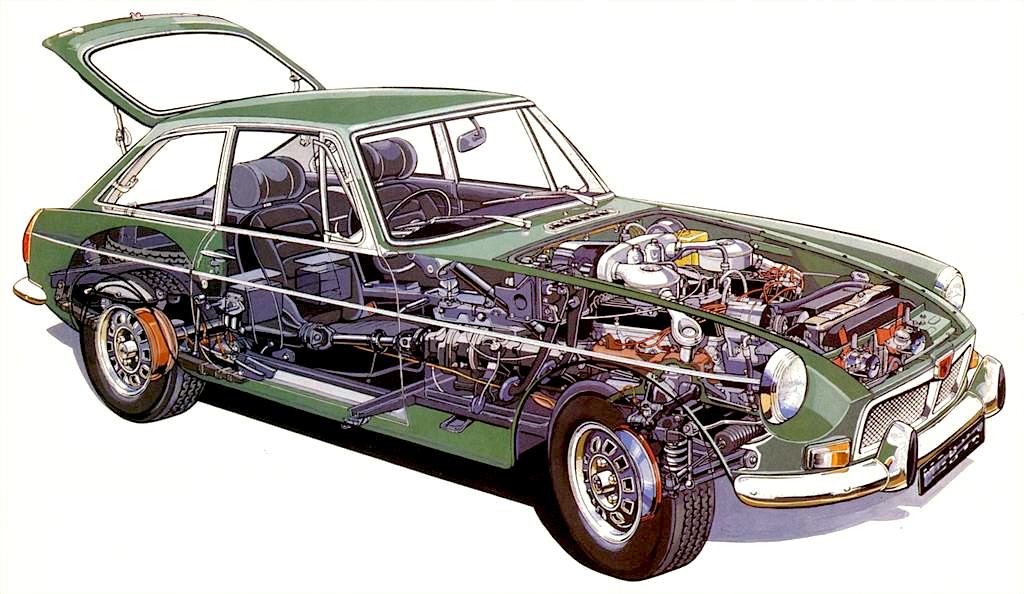

During its 18 years of production, the B, in all its shapes and forms, enjoyed an almost cult status. It endures today as one of the best-known British sports cars. It was the first MG to use monocoque body construction, enabling it to meet increasingly stringent crash-testing demands.

Called in to style the new hardtop MGB GT, Pininfarina surprised many with his very practical three-door hatchback design, introduced in 1965. Apart from having almost the capacity of a station wagon, it was a far cry from the earlier upright TD/TF models followed by the rounded styling and flat floor of the MGA models it replaced. Power was provided by an enlarged version of the venerable B-series four-cylinder engine, now out to 1800cc. There was an automatic transmission option in 1967. Whatever would purists think! Not much apparently, as just 5000 units were made and it was dropped in 1973.

The B was a success story for BMC, but under ’70s Leyland ownership it might have done better had its masters heeded sound advice and better managed US safety and emission requirements. US market models received suspension inserts to raise the height of the headlights to comply, and heavy rubber bumpers at both ends not only changed the B’s looks but diluted its previously nimble handling.

Costello’s V8 conversions changed the character of the MGB, using Rover’s 3.5-litre alloy V8 — just a few kilograms heavier than the B-series engine. Leyland engineers said it couldn’t be done but they obtained a Costello V8 to sample, putting the model into production. Abingdon production ceased in October 1980 and the home of MG closed shortly after. Some 9000 CKD roadster kits were shipped to Leyland’s Zetland, Sydney, plant between 1963 and 1972. More than 500,000 cars were produced throughout the B’s lifetime.

In 1980 British sports car manufacturer Aston Martin Lagonda (AM-L), in an attempt to offer an entry-level-priced AM-L sports car, put together a proposal to buy out MG, including the MG brand name and the Abingdon factory. Engineer Keith Martin and designer William Towns put together a design and one prototype. The prototype was wheeled out of the AM-L workshop on 25 June. It sported a very upmarket look and subtle styling changes, including a higher windscreen, among its numerous luxury changes. An offer of £31 million was made to Leyland but it declined to let the marque name go and the deal failed.

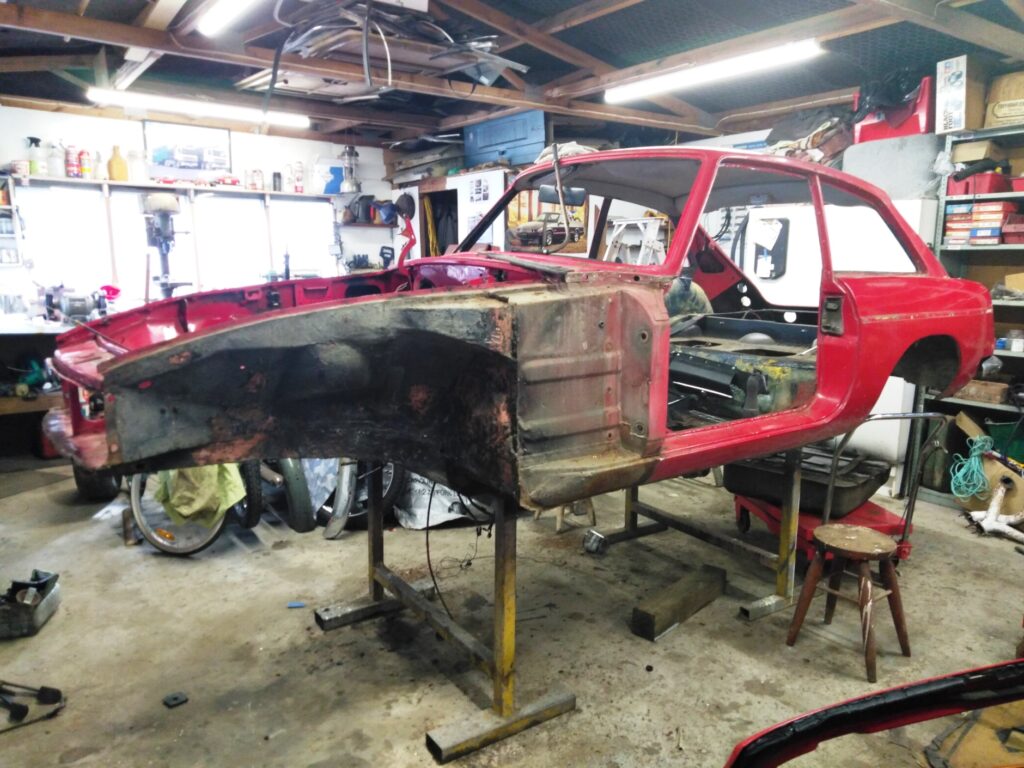

Restoration nightmare

Auckland classic car enthusiast Kerry Bowman soon realised he had a massive job on his hands in restoring his classic 1968 MGB GT. When Kerry and his MGB first appeared in New Zealand Classic Car in March 2021, in “Behind The Garage Door”, the stripped-out shell had revealed some nasty surprises. Once the true extent of the hidden damage was discovered, the work would normally have been handed over to a professional fabricator. However, with the assistance of experts such as MG specialist restorer, Paul Walbran, Kerry has completed an impressive restoration and saved this car from the scrapheap.

The self-confessed Citroën fanatic had just finished the complicated restoration of a very rare French Citroën Birotor (Wankel, twin rotary engine) sedan, featured in New Zealand Classic Car in June 2021. An Indian-built Jeep and a Citroen 2CV had previously benefited from Kerry’s restoration skills. Along the way he also managed to race Mini Coopers for some 14 years — taking part in the final race meeting at Bay Park, Tauranga — and ran in three Wellington Street Races.

Never one to sit around, Kerry’s philosophy is quite simple and expressed with some amusement, “You have got to be doing something, haven’t you? I never quite envisaged, though, just how challenging this MGB restoration would become.”

Kerry’s 1968 MG was first registered in New Zealand in 1969, in Palmerston North.

“It ended up in Auckland in the hands of some woman who spent a lot of money on it; I have all the receipts,” Kerry says. “She had the engine rebuilt. Back in the late ’80s or early ’90s, she must have moved to Rotorua where she had a power of money, about $10,000, spent on the car, just getting the rust fixed.”

Kerry has reconstructed what was essentially a ‘parts’ car into the vehicle you see in this feature, which also highlights how the faults in the car were well hidden and a real trap for those without Kerry’s skills. If all this work had been completed by a professional then the cost would have been substantial, as Kerry explains.

“I could have bought a new shell and, in hindsight, maybe I should have. You get committed and you get so far. I think the shell and the components to rebuild the shell cost me about $25,000, and it’s cost me in excess of $60,000 all up. It’s a car that perhaps, at its stage of life, should have gone to an MG enthusiast that wrecks them.”

Burning the midnight oil

Kerry removed copious amounts of thick underseal from both the underside and inside cabin panels of his car. With repairs from a collision not competently completed, it was obvious substantial areas of sheet metal would need replacing.

“From the front of the rear seats forward is all new; new rails, new cross members, and new floor box sections. There were new inner and outer sills. I then had to fabricate some parts as I couldn’t get a replacement, such as the left-hand A-pillar from below the scuttle to the top of the sill. They had banged it forward and obviously got the door to work, and the front of it was just punched in!”

Kerry now faced rectifying these faults.

“I thought, ‘The door works, but you can’t leave it because somebody will take the front guard off and say what has this thing hit?’”

With all panel measurements now correct, the shell was ready for its doors — then Kerry discovered further problems.

“There was the (new) left-hand lower section of the bulkhead that we had to put in; the only remaining bits at the front of the car that were there when I bought it were the inner guards and the bonnet. New door skins were added because I couldn’t get the gaps. Then we discovered the doors were actually hanging over the sills. I measured it and Paul (Walbran) made new door skins for me, and the ones on the car were 4mm longer.”

The rear outer mudguards from the door to the tail lights were replaced, as were the two-piece inner mudguards, which were so rusted there was nothing to mount them to. The front suspension also presented some issues.

“The lower arms had been bent and had been beaten straight,” Kerry explains. “On [the left side] at the rear of the bend that goes across under the engine, there was an 8mm piece of plate taking up all the buckling! I cleaned up the bottom arms but this was too dangerous and ended up buying new ones, along with new kingpins. It also needed new front hubs, as the splines were worn out, and new discs were fitted.

“I rebuilt the calipers [of the front disc brakes] but when it came to bleeding them there was a leak in the right-hand side one. I couldn’t quite see it so I jumped on the brake pedal to see if I could squeeze a bit of fluid out and see where it was coming from and blew the bleed screw out. The caliper was cracked.”

Now completely rebuilt, the front suspension was painted and refitted. The front wire wheel splines were worn so two new wheels were bought as it was cheaper to buy new than repair them. The rear wire wheels were also replaced later; they were discovered to be bent when the new tyres were being fitted.

Underfloor gremlins

Now, with everything back in its proper place, it was time to tackle the underfloor area of the cabin.

“The whole car had been undersealed and undersealed. It was difficult to cut the panels out as it kept catching fire. I found the chassis rail was split — that was all hidden under this black underseal. When I dug more away, I found the bulkhead was pushed back in. The floor inside was undersealed as well as the bulkhead, so I cut that out and it just went from there.”

Built as a convertible to meet the crash-test requirements of the day, the MGB has a detailed inner sill construction made up of three panels and a castle rail to maintain structural integrity. At some stage, some dodgy rust repairs had been carried out and some internal strengthening panels had been omitted, as Kerry discovered.

“When I first looked at the sills they were solid and there was no evidence of filler in them. There was a little bit of rust in the bottom of the front guards and at the top. There was a bit of rust in between the door and rear guard and rear wheel arch at the bottom. I thought, ‘Structurally, yeah, it looks OK’. I thought that with a retrim and repaint it would be a new car, but once you start taking things off — well, it doesn’t stop.

“When the guys put the sills on they had the front and rear guards off. They had cut the sills behind where they cover the join and cut the centre of the sill out and put a new piece in but no inner sills! They had gone. There are normally three pieces to the sill and a castle rail underneath but the GT gets away with it because of the roof for strength. I also put a new castle rail in.”

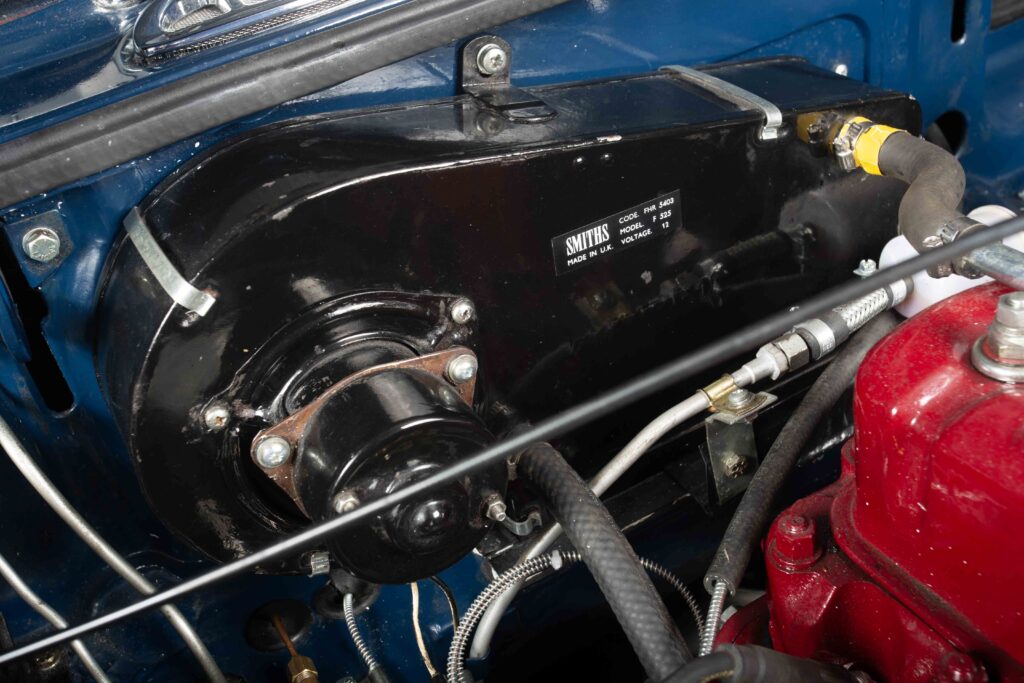

A replacement firewall was fitted, and at last, all the major work was done. However, there was still a long list of tasks to be completed. Kerry sought many of the parts from UK suppliers; most of the reproduction parts were available, and Paul Walbran provided assistance in bringing in the parts.

The slightly warped rear hatch door was repaired and coaxed back into its correct shape. The current bonnet, although carefully repaired, is not quite as Kerry would like and a new reproduction alloy item will be fitted. With its attractive new dark-blue colour scheme, the car now looks a completely different proposition from when Kerry started. He finished it off with a stone-resistant chassis paint underneath.

Back on the road

In March, the MGB was ready for its first road run, and Paul Walbran asked Kerry to display it at a recent MG Car Club outing. Despite a few teething troubles, it went well.

“I was pleasantly surprised when I took it out on the road,” he tells us. “The overdrive also worked fine on third and fourth gears.”

An amusing anecdote to the restoration was an email one day from the Transport Agency, advising Kerry he no longer owned the MGB as someone else had tried to register it. A call to the agency quoting the car’s registration sticker number soon had this sorted, but it was a lesson in how easy it is to manipulate the system.

“Someone was obviously trolling CarJam and found this MG — which had had its rego on hold for just over a year at that stage — and thought, ‘That’s never going to go on the road anytime soon’ and they were going to steal it. The system is easy to get through.”

Restoring his MGB has been a satisfying project for Kerry.

“It’s been an interesting job, and you wouldn’t have done it if you couldn’t! If somebody bought this car and gave it to a company to rebuild, [they would] probably be looking at well in excess of $100,000 to do it, because [the company would] buy the parts, put a bit of a mark-up on them, then charge labour, so it wouldn’t be cheap.”

Kerry was philosophical about the challenges of making it into a safe car to drive.

“There were a couple of times I would get out my garage stool, sit on it, put my head in my hands, and ask why I was doing this. Sometimes I just walked out of the shed and shut the doors and came back the next day. I then looked at it in a different light and said, ‘Yep, I’ve stuffed up and I’ve got to fix that’ — then you can press on!”

MGB SPECIFICATIONS: (UK Market specs)

Engine:

Designated 18GB — five-bearing motor from 1964 — water cooled in-line four-cylinder petrol engine, single side-mounted camshaft with cast-iron cylinder head and two overhead valves per cylinder, twin side-mounted SU HS4 (HIF4 from 1973) carburettors and SU electric fuel pump, 9:1 compression ratio

Bore/stroke: 3.153in (80.26mm) x 3.46in (88.90mm) for 1789cc or 109.8cu in

Power: 94bhp (63kW) @5500rpm

Torque: 105lbs·ft (143Nm) @ 2500rpm

Transmission:

Four-speed manual — all synchromesh from 1965; optional Laycock overdrive, BorgWarner 35 automatic 1967–1973

Suspension:

Front: sub-frame, wishbones, and coils springs, top arm doubling as a lever arm shock absorber, anti-roll bar rear: semi-elliptic leaf springs, lever arm shock absorbers, rear anti-roll bar added 1977

Steering:

Cam gears rack & pinion

Brakes:

Disc front, 10.75in (273mm), drum rear, 10in (254mm)

Wheels:

Steel disc or wire wheel optional: 4.5J x 14 — later cars had optional alloy wheels; tyres: 5.60 x 14, 165/80 x 14 radials standard tyre fitment

Body details:

Monocoque 2 + 2 hatchback and two doors

Wheelbase:

91in (2311mm)

Track:

Front: 49in (1245mm); rear: 49.3in (1251mm)

Weight:

2442lbs (1108kg)

Length:

158.3in (4020mm)

Height:

51in (1295mm)

Performance:

105mph (169kph); standing quarter-mile: 36.4sec @ 146kph