John Hancock’s 1938 MG TA Tickford garnered the highest score of all the cars entered in the 2019 Concours D’Elegance at the Ellerslie Classic Car Show. It’s easy to see how

You can’t help thinking that this car is better than new. Drink in the flawless paint; the deep gloss on the walnut dashboard; the taut hood with ruler-straight stitching; and, above all, the tight shut lines of the bonnet and doors — you can’t imagine them being this good straight out of the factory in Abingdon or even from the Tickford coachbuilders in Newport Pagnell, where this one came from.

MGs of that era were hand built by craftsmen, but there were still production targets to meet, and there was always the next car coming down the line or, more accurately, being pushed across the garage.

John bought the car sight unseen, apart from some pictures from a dealer in the UK. He had dealt with the dealer before and trusted his judgement, but it was still a relief that the car arrived pretty much as described.

“It was a wreck,” says John. “Not physically damaged, but it had clearly sat outside for many many years, as they tend to do in the UK. The guards were not too bad, but the body had gone. We had enough of the body to make patterns, but the firewall area was very rusted out.”

Tickford bits kept safe

Crucially, almost all of the bits were there.

“Fortunately, they had taken the Tickford hardware off and stored it inside,” John says.

This was one of the 260 or so TA chassis sent from MG to Salmon and Sons Ltd, which produced the deluxe Tickford drophead model. That necessitated different and wider bodywork to accommodate substantial ironmongery and taller doors with wind-up windows. The result was a lined hood with three positions: closed, open above the seats only, and folded — for a total cost about half as much again as the standard car with a two-bow hood.

Apart from the hood’s spectacular, curved, pram-style folding stays and the taller doors, Tickford T-series cars can also be identified by their bucket seats — standard TAs through to TDs had bench seats. Another clue for the cognoscenti is that they also feature body-coloured radiator grilles; on the standard cars, the grille colour was chosen to match the interior trim.

When John brought the car into the country 20 years ago, it was the only TA Tickford here, but a couple have arrived since, he says. John finished the car just days before this year’s Ellerslie show, a much-needed deadline after he started the restoration 20 years ago, allowing time for restoration of other MGs and house renovations.

The bodywork took the longest. Some of the body’s ash frame was rescued, and John used the rest as patterns to make new frames himself, which a bodybuilder then reskinned in steel to create a new tub. He also repaired rusted sections in the lower ends of the guards.

Decaying wood and rusty shapes

Both doors were little more than decaying wood and rusty steel shapes. The window-winding mechanisms were recoverable, but the doors had to be remade from scratch. They are incredibly heavy, John says. The hinges were flogged out, so he bushed them and installed new bolts. Positioning them so the door swung freely was as much fun as you can imagine it would be.

The switches and instruments were all present. Some were revived, but others were replaced.

“It’s all standard Lucas stuff and readily available,” he says.

The walnut dash was beyond resuscitation. John had a router bit made to match the milled edge on the old one. He made the new dash and door capping himself, which he finished with many coats of varnish. The seats and door panels were missing, so John bought new, trimmed with English Connolly hide. Door seals and trim are also available new. The floor mats and carpet trim were made here, but from carpet that someone in England had had remade to the original Tickford fleck pattern.

He sourced and added some period small lights to either side of the new fuel tank to function as rear indicators. Originally, TAs wore only the round combined stoplight and number-plate lights. The semaphore-flag-type trafficators that pop out of the bodywork are present but have been disabled for compliance. The spotlight that sits on the badge bar at the front of the car is apparently one of the rarest items in MGdom.

Regrettable whimsy

John was a frequent visitor at MG swap meets on trips to the UK. He found the spotlight mounted on the driver’s side A-pillar at one such swap meet and thought that it would make a good period addition to the car. He drilled the holes in the pillar for it years ago but, when it came to installing it and making it work, he had plenty of time to regret that whimsy.

The lamps, windscreen frame, Tickford hood hardware, and other brightwork were re-chromed, while John made up a new metal frame for the glass rear window and a couple of small plates that were in bad condition on the original bodywork.

He spent a long time lining everything up perfectly when the car was wearing just its undercoat.

“Yet, when you paint it and try to put it back together, for some reason you have to fiddle everything again,” he says.

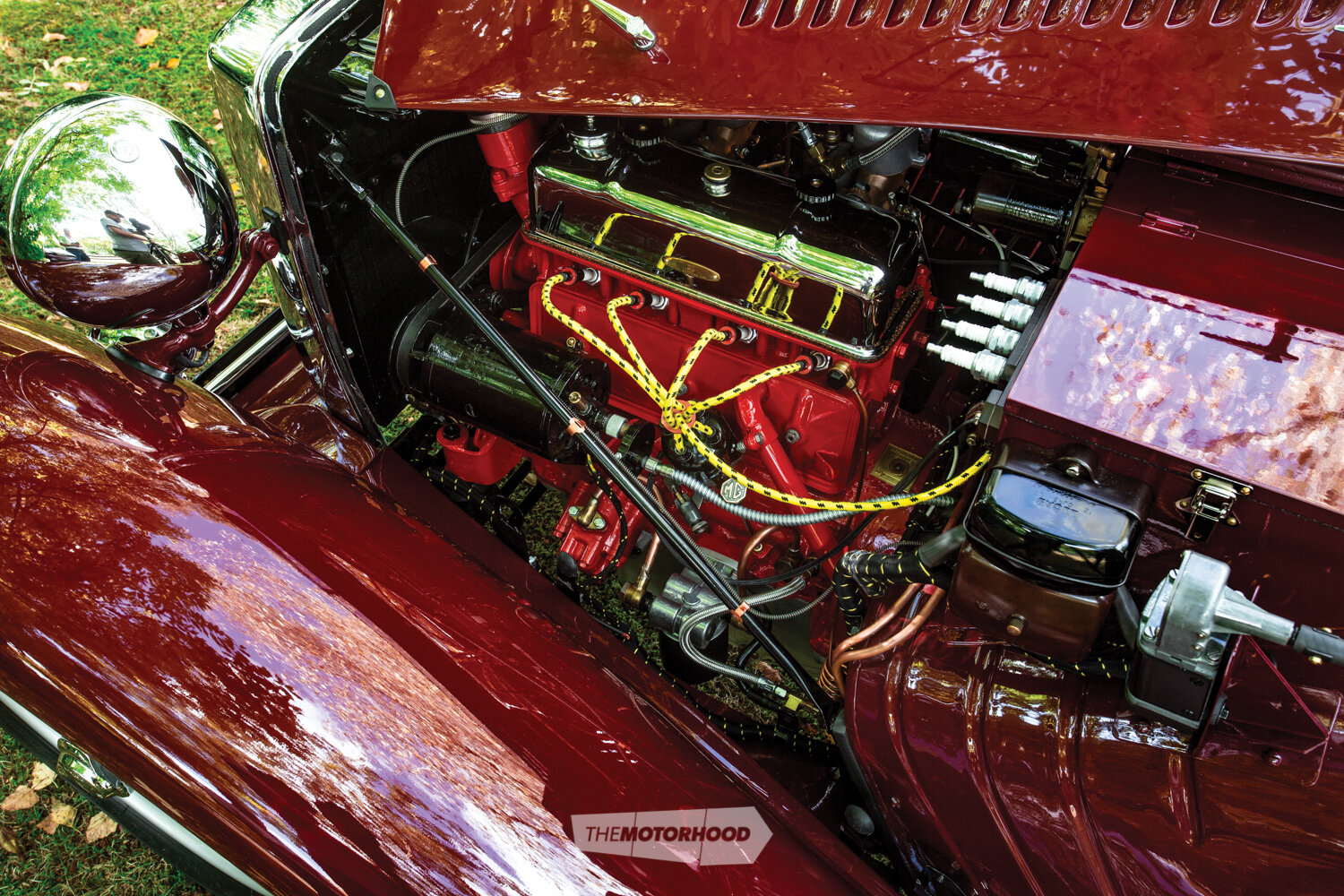

The 1292cc engine was knackered. It was missing the odd thing like a water pump, but parts are readily available through MG club sources or at swap meets. John stripped and rebuilt the engine, chassis, suspension, and running gear with the help of an engine shop, which did some machining.

“Apart from the Tickford body, it’s just very standard MG,” he tells us. “They are just very simple cars and well known. There’s a large network of people out there and all around the world.”

“A wonderful club”

He says the MG club is “a wonderful club to belong to”, especially when it comes to restoring cars. At various times, people have remanufactured many of the rarer parts.

“If you get stuck, there’s always something out there in various stages of disrepair and anything can be fixed,” he says.

The chromed rocker cover looks like a later addition, but John explains that it was standard on the TA. MG reverted to paint for later models. The yellow spark-plug leads also look a bit bright, but the fabric covering is absolutely period correct. A complete factory toolkit is also present and correct.

The wheels, tyres, and brakes also look brand new. That’s because they are. John has expended a fair bit of effort trying to resurrect old wheels, before concluding that it is a waste of time. There’s not a lot you can do with worn-out splined hubs, so now he always gets new hubs and wire wheels for his project cars. That also puts any issues with spoke tension into the distant future. The brake drums are also new.

The car has just a couple of non-period pieces “that you are not going to hear about”, says John. We spotted one: a battery isolation switch on the panel behind the driver’s seat, but no blame can be attached for that.

A regular in the winner’s circle

This isn’t the first MG that John has put in the concours winner’s circle; including this one, three MGs of his have comprised one-half of an MG team entry. His other winning cars were an MG TD and an MG K1 fitted with a supercharger. He raced that car in classic events here and in France.

“I had done what I wanted to with it,” he says about his decision to sell it, although you can sense a touch of remorse. “It was a car that could do it all.”

There’s no doubt the TA, in its glorious dark red paint, is a looker. Tickford cars were available in any colour, so he gave himself a free hand. The T-series Midget has an appeal all its own. Its post-war successor, the TC, which had a 100mm wider body, narrower running boards, and a better engine, is credited with sparking the US interest in sports cars. This car’s square lines are complemented by the flowing guards and the taut padded hood.

John is mightily impressed with the work of the car trimmer in Manukau who made the hood. He had spotted some of his work on an American car’s interior at another car meet. This was the trimmer’s first Tickford hood, but John’s confidence in him was well placed.

“He’s probably the only person I know who is as fussy as me,” says John.

Dismantling the hood is a two-person job. John had never done it before, as fitting the hood was one of the last jobs completed prior to the show. We reach inside to the top of the windscreen and undo two butterfly nuts. That releases the front fold. Then we work two levers that release the hood from the frames on top of the doors, that we rotate inwards until they are facing across the cabin, behind the driver’s head. We fold the levers forward to align with the arms again, then place a sock over each.

A three-position hood

The hood is then rolled back, and two straps on the underside of the hood come up and out and hold the roll and the rotated door frames in place. We should have rotated the roll onto the top of the hood to give more headroom, but this is stage-one complete. You can drive the car like this, or you can drop the hood completely. Release two more catches, push the knee joint in the pram brace, and the whole thing folds neatly backwards.

Lowering the hood transforms the look of the car. John is often asked if he is going to pinstripe the raised body moulding along the side of the car. It would make the look longer and lower, but a good deal of this car’s cheeky charm lies in its upright stance and solid colour. John isn’t tempted to pinstripe.

As we bounce over the potholes back to John’s house, I ask if it feels like a sports car to drive. John is emphatic.

“No, it feels its age. Any modern car is so much more capable, but this is so different — it’s fun in its own way.”

As a driver’s car, John prefers his 1962 MGA, in which he and his wife Brenda toured the South Island this summer. A couple of simple upgrades have given it the same 100hp (75kW) as an MGB, so it cruises easily and keeps up with modern traffic. John says that he and Brenda will take the TA to the Napier Art Deco Festival next year, but he’s far from certain that they will drive it there.

In the meantime, there’s an MG TF in bits in the garage, awaiting John’s expert attention.