BMW’s 3.0 CSi was always a class act but appreciation of its timeless beauty is accelerating as swiftly and smoothly as its sophisticated straight-six

By Ian Parkes, photography High Art Photography

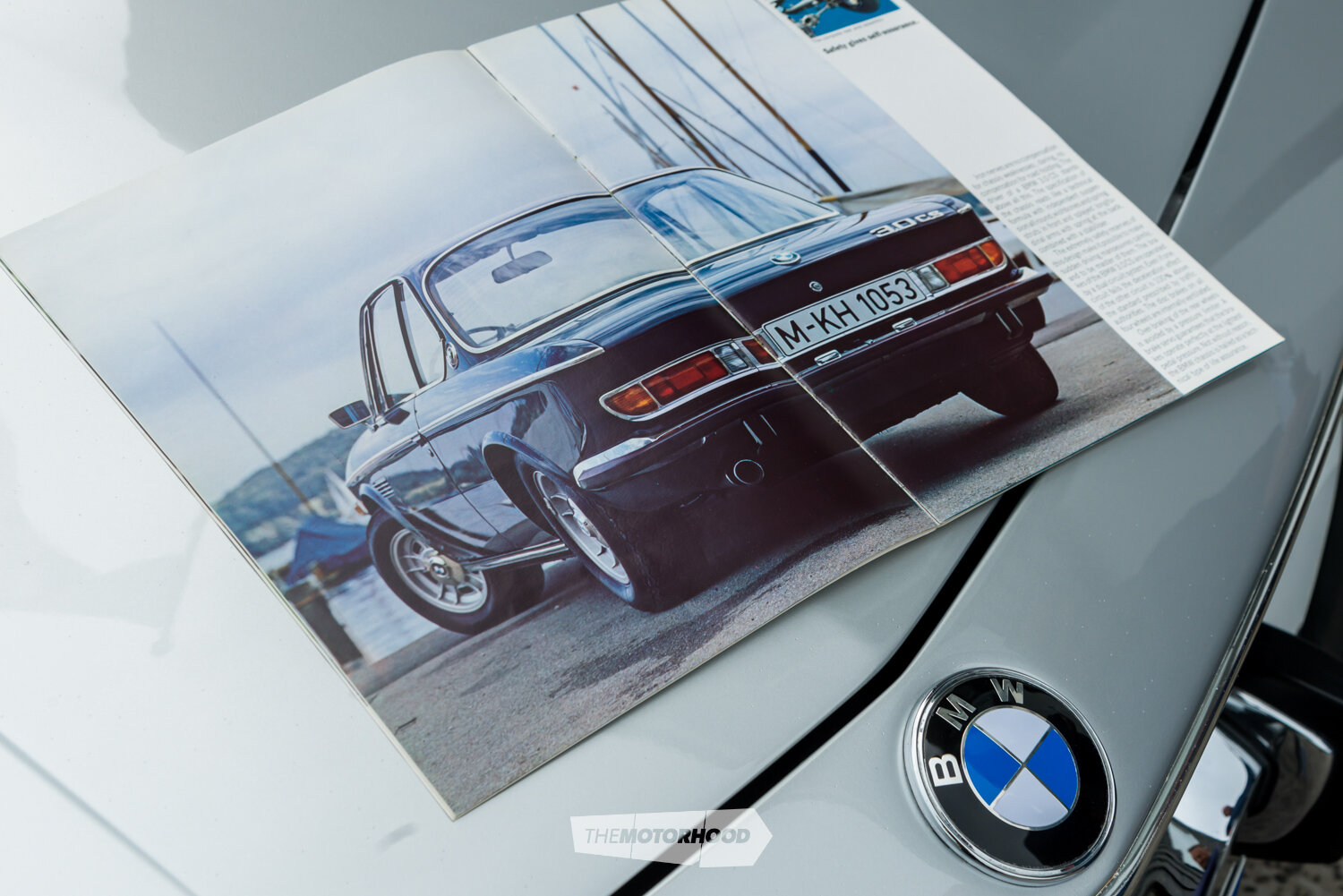

New Zealand Classic Car is not exactly going out on a limb here but we have to say this is one of the most beautiful car shapes ever created.

The lead designer was Wilhelm Hofmeister, BMW’s head of design from 1955 to 1970 — he of the ‘Hofmeister kink’. That label is applied to the distinctive curve at the base of the C-pillar that has been a signature of BMWs ever since Herr Hoff introduced BMW’s Neue Klasse cars. Loosely defined as cars produced between 1962 and 1977, they put the company on a firm financial footing and established its reputation for building sports saloons and coupés.

What is more remarkable, as BMW Car Club of America’s Rob Siegel has noted, was that the 3.0 CSi’s sublime shape did not crystallise fully formed from an inspired vision, but was a development of a slightly weird and relatively unknown predecessor, the 2000C/CS, a two-door coupé built from 1965 to ’69.

“Considering that the E9 was not drawn on a clean sheet of paper and instead evolved from the 2000CS, the degree to which it looks like a ‘perfect from the get-go’ design is astonishing,” says Siegel.

The eye of the beholder

As our photographer dances around it, and I move to keep out of his way, it is tempting to keep interrupting and say look at it from this angle … and from here … and here. The fact is, it looks pretty much perfect from every angle.

Owner Kevin Billing agrees. He has always been a BMW fan — in fact, on the day we visit he is flying a BMW flag above his Cockle Bay home. He says he has about 30 different flags, which he swaps out as appropriate, depending on the nationality of visitors, or the enthusiasm of the moment — of which he has plenty.

The 3.0 is parked alongside a more recent acquisition, an M635CSi. Now that is also a handsome, head-turning car that would be near the top of any coupé fancier’s list, but beside the E9 it looks just a bit ordinary. It could be the case that BMW hit the sweet spot with the E9, which gave the lines of the 2800 and the 2002 just a bit more breathing space.

Was it also a peak? After drinking in the delicacy of the E9’s wine-glass profile, subsequent models have looked either too anodyne or have an excess of creases and folds that — rather than adding distinction — have simply made them look more like many other cars. Kevin says the reaction is the same wherever the car goes.

“I just like the shape — but everybody does. They just walk all around it. They just love it,” he says.

Kevin remembers the first time he saw one in the metal: “I was at Jensen Motors one day in 1984. I saw one of these and thought Wow! I loved it but it was way too expensive at the time. I’ve always loved them.”

BMWs forever

Kevin says the first thing that caught his eye, as a child, was the blue roundel badge. He was soon devouring everything he could read on Bavarian Motor Works.

He bought his first BMW in 1977. It was a first-generation 3 Series coupé, a 1976 (E21) 320 in Inka Orange. Next he got an E28 525i, then he went for a series of 3 Series saloons, starting at the top with the iconic M325i. Kevin was a panel beater so he wasn’t put off by the frontal damage that made it a write-off. Since then, he hasn’t been without a BMW in 44 years.

While he has been a canny purchaser of BMWs, like most of us, there are a few cars he regrets having let slip through his fingers. One was a 3.0 CSL, the ‘L’ denoting the lightweight body, a homologation special made for racing. As well as having an aluminium boot, doors, and bonnet, it was made from thinner metal, had plastic windows, and various creature comforts were deleted. The dealer, who knew Kevin was looking for a 3.0 CSi, wanted $25K for the car in the mid ’90s. Kevin thought it was a bit dear at the time. A couple of years later, the dealer was back with a CSi. It was in rough condition but Kevin thought it was fixable. It was $10K, so he bought himself a project.

Karmann karma

There were two things making this more of a project than Kevin had hoped for. The car had come from England so had suffered a lot of corrosion from the salted winter roads and, like all of the 3.0 coupés, it had been built for BMW by coachbuilder Karmann, the other half of a famous classic car cliché couplet. The first is that Lucas is the prince of darkness, and the second is that Karmann invented rust then licensed the process to the Italians.

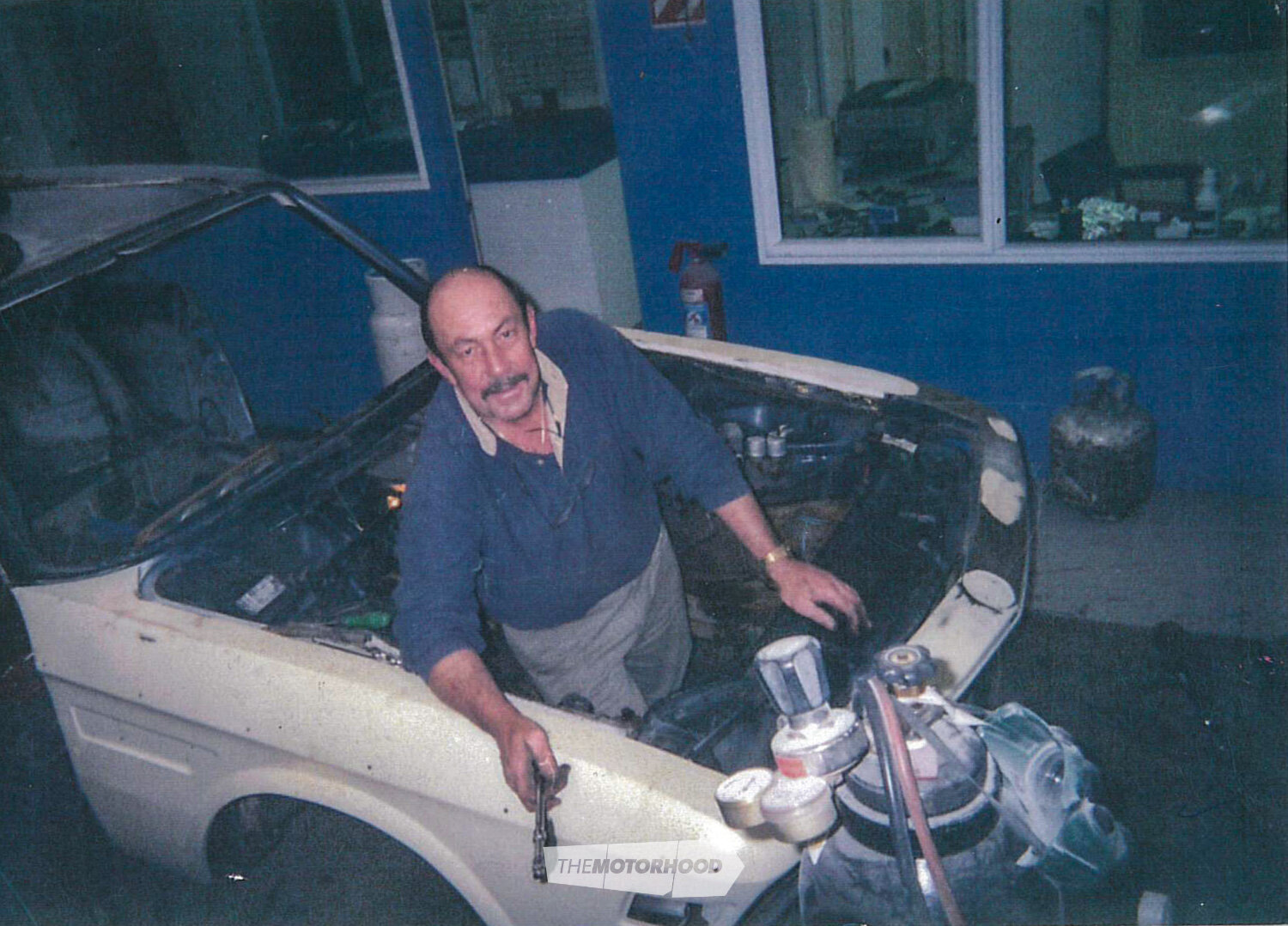

Kevin said the doors and floor had been patched with bog and there was fibreglass in the firewall. After a couple of years of part-time work on the car he decided he had been chasing his tail long enough. Eventually he found another body that was 75 per cent complete — a 1972 CS, carburettor model — at SD European wreckers, north of Hamilton. He bought it for $5K. The first owner of that car was BMW importer Ross Jensen.

Around this time Kevin sold his panel-beating business to his foreman and set up a truck-painting business. Most vehicles arrive in the country with a white cab, black chassis, and silver wheels but most companies want them in their own colours. Kevin says there was a gap in the market then.

While building that business, he went through thousands of parts to make one good car out of the best bits of both donor vehicles. He also sourced many new parts from specialist suppliers, to replace parts that were worn or plastic parts that had degraded over time. He can’t recall any parts that were hard to find. In fact, the opposite. He ordered a wiper-control system on a Friday from a supplier in the UK and it was at his workshop on the Monday.

“I can’t get anything from Wellington that fast,” he tells us.

Not heavy metal

Interestingly, for someone who ran a truck-painting business until he sold it and retired in 2016, Kevin didn’t paint the car himself. He prepared the body but got a technical specialist from the paint supplier to spray it. Kevin was intrigued by his technique. He watched him paint the boot lid from outside the booth and says he must have made more than a hundred light passes over it with the spray gun, barely misting the air each time. Three coats of base and a couple of clear. It took him over eight hours.

“Metallics are hard,” Kevin says. “That’s why you see a lot of silver resprays that don’t look right; they put it on too thick.”

It took Kevin about five years of his spare time, outside of his business and other interests, to finish the car. He stripped the car himself and did all the mechanical and bodywork except for the motor. After it was repainted, when he had all the bits to hand, it took him about two months to put the car back together again.

The car’s first event after completion was a BMW festival at Hampton Downs, where it picked up the Best in Year and Best Car of the Show titles. Kevin says people can’t resist a good CSi.

“I think it’s the whole shape in general,” he explains. “You put the windows down and it’s pillarless. It’s got a look all its own. For a 1972 car, it was way ahead of its time.”

Seventh heaven

On the strength of the CSi’s popularity with BMW fans, Kevin agreed to be part of a BMW two-car team entry, with a yellow CSL from the Bay of Plenty, in the Ellerslie Car Show’s Intermarque Concours d’Elegance. It was his first concours and he didn’t really know what to expect. Someone said he just had to clear his stuff out of the boot, that sort of thing.

“We got crucified,” says Kevin. “I got pinged because the spare-tyre pressure was too low, a bit of the wiring loom had paint on it, and the underneath was dirty. We got seventh out of seven. It was quite funny.”

Kevin is not a slave to originality. The interior of this car has also had a makeover. He replaced the hood lining with black material — BMW spec, but it wasn’t an option in 1972. It works well in this car, where the interior is brightened with plenty of chrome and woodwork.

The blue velour seats were worn so they were recovered in a new black BMW fabric by Stitches Upholstery in Clevedon. There was a fair bit of wood trim in the fascia and on the doors that also needed restoring. The upholsterers put Kevin in touch with an Englishman who used to restore pianos. It now has a lovely lustre that is rich but not too bright.

The Alpina wheels also look just right, although they were not original fittings. They came from a 5 Series Alpina saloon — Alpina is a specialist BMW tuning company — that had been damaged and left to rot under a tree. It was in a terrible state. Kevin and a friend bought the wreck for $2K — $1K each. When Kevin opened the door, it fell off. His friend wanted the gearbox for a race car and Kevin wanted the wheels. Kevin got five for $1K and had them stripped and repainted. Then they sold the rest to a wrecker for $1500. It felt like good business at the time but now Kevin thinks another rescue mission, with another body, would have been a better move. But that would have required space he didn’t have. Hindsight is a wonderful thing.

If it ain’t broke

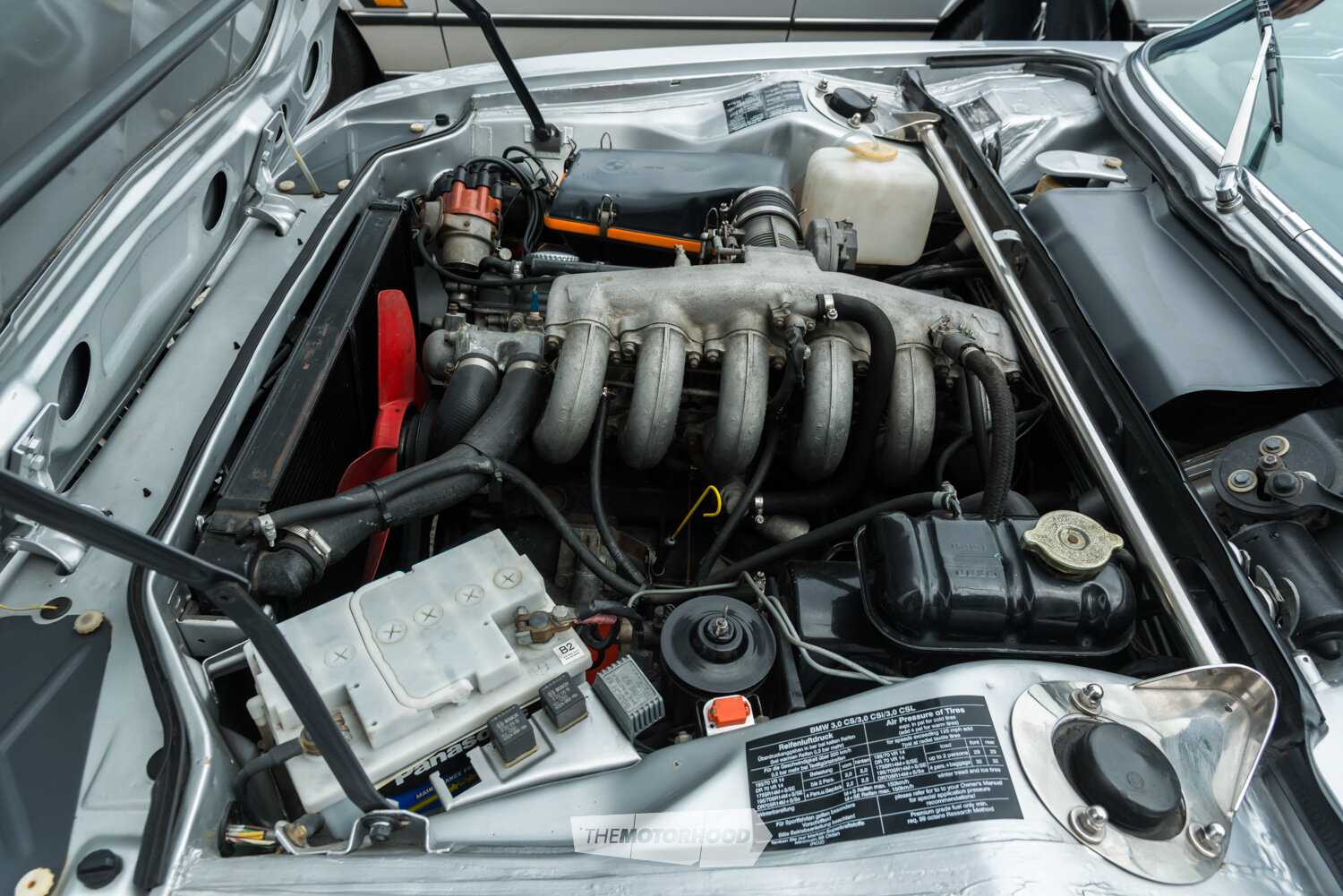

Under the bonnet the car wears all the correct labels and stickers. It also sports a stainless-steel brace between the shock towers. It’s an aftermarket piece that Kevin now feels inclined to take off. It was just a bit of bling and he can’t tell it makes any difference even when pushing hard.

BMWs were always partial to a bit of automotive electronics and, while this 1972 car came from early on that curve, I ask Kevin if any of the electronics had given trouble or were difficult to replace. He can’t think of any. He says the car had the first commercially available electronic fuel injection, Bosch D-Jetronic, which also found its way onto some Volkswagens, Mercedes, and Volvos. He says the control unit for that is under the rear seat and looks like an old transistor radio, but it still works perfectly.

Kevin did replace the injectors on the car, a pricey exercise in the mid 2000s when they cost $380 each. He also had the starter motor, alternator, and suspension bushings rebuilt.

“If something needed doing, I’d just send it off and get it done,” he explains.

Nothing has been done to the block and the motor has now done more than 400,000 miles (nearly 650,000km). That is not unheard of but is quite impressive. And apparently the motor doesn’t burn any oil.

We go for a quick drive around the neighbourhood and Kevin isn’t averse to showing off the car’s sporting credentials. The engine response and handling is surprisingly sprightly.

I comment on the filled-out but refined engine note, courtesy of the evenly spaced firing intervals of the straight-six. Kevin immediately agrees.

“Oh, it’s great.”

V8s are all very well — if you like that kind of thing.

Serenity

It’s also pretty quiet. The exhaust system, full stainless, came from the second donor car. It was in near-new condition and is still playing a lovely tune 10 years on. What’s also noticeable is how quiet the rest of the car is; how little noise the body makes, especially for a pillarless design. Inside, it’s an airy and roomy car. The lack of windows, electrically lowered on one side, accentuate that but any support from glass pressed firmly into the surrounding rubbers is gone yet nothing gets floppy.

I fully expected little squeaks and rattles from a car of this vintage but, as Kevin swings it around traffic islands and boots it uphill, you notice how tight and together it is. Drawing on his experience with the car, Kevin has chased down some stray noises but the well-set-up suspension means there are also no clonks and thumps.

Kevin is clearly relishing sharing his pride and joy, and says that he enjoys driving it more than its more modern stablemate, the M635CSi: “The 3.0 cruises along just nicely. That thing [the M6] is just go, go, go. It just wants to be driven. It’s a seriously fast car and you want to drive it like a race car.”

It shares the same engine block as the 3.0 CSi but benefits from a few more years of development. Kevin has driven both cars down to the beach house at Pauanui and says that the M6 is better on the open road, on a trip, but the E9 is a much nicer car to drive around town.

Nice to have the choice. Kevin has only recently bought the M6. He had taken the E9 to a regular classic car meet on the North Shore and had often seen the M6 there. He finally met the owner. They both were glad of the opportunity as they both wanted to buy the other person’s car. Both said their own car wasn’t for sale. But still they talked. Eventually, the other owner flinched. He also owned Jaguars and wanted to buy an early XK that was in need of restoration, so he decided to let the M6 go.

The M6 is a hell of a car, but you could probably get two of them for the price of a good 3.0 CSi. Such is the price now commanded by the E9’s beauty — cars that could once be had fairly readily for $10K a pop — that you won’t get a good one now for under $100K.

This article originally appeared in New Zealand Classic Car issue No. 363