Ferrari owner and enthusiast Roger Adshead got to wondering where the simply beautiful twin tail lamps that are a signature of many Ferraris came from, and what inspired them. It led him on a fruitful journey

By Roger Adshead

There are no more defining or memorable Ferrari design cues than a pair of twin circular tail lights, which find their echo in the rear valance in two pairs of circular exhaust tips.

Introduced fifty years ago by Pininfarina designer Leonardo Fioravanti, this charismatic Ferrari identifier has more than stood the test of time.

They first appeared on the Dino 206, and then on the 365 GTB/4 Daytona, two of Signor Fioravanti’s most revered designs.

Unlike Pininfarina’s trademark slim vertical tail lights of the 1960s, which subsequently found their way onto the mass-produced Austins, Morrisses, and Peugeots of the period, the twin circular tail lamps remain emblematic of Ferrari supercars and sports cars.

Some earlier Corvettes copied them, and they have been partially mimicked by Golf Mark V and Honda Civics of similar vintage, and it’s probably no coincidence they added some visual flair to Nissan’s high-performing Skylines, but they have been a recurring theme on Ferraris right through to its latest designs.

Once you have noticed them, it’s surprising how often they seem to be overlooked in photographs of Ferraris, especially when the front ends of many Ferraris have struggled to find a theme with similar longevity. Could it possibly be that they are too common, in that that is the view that most people see on the open road, like dual jet engine afterburners disappearing into the distance?

It made me wonder whether this may have been Fioravanti’s inspiration. I am also reminded of a menacing Vulcan delta-wing bomber that I once watched climb from a near-vertical stall, and with an increasingly thunderous roar, into a heavy storm-filled sky, all four circular exhausts emitting the famous Vulcan howl.

A Letter From Turin

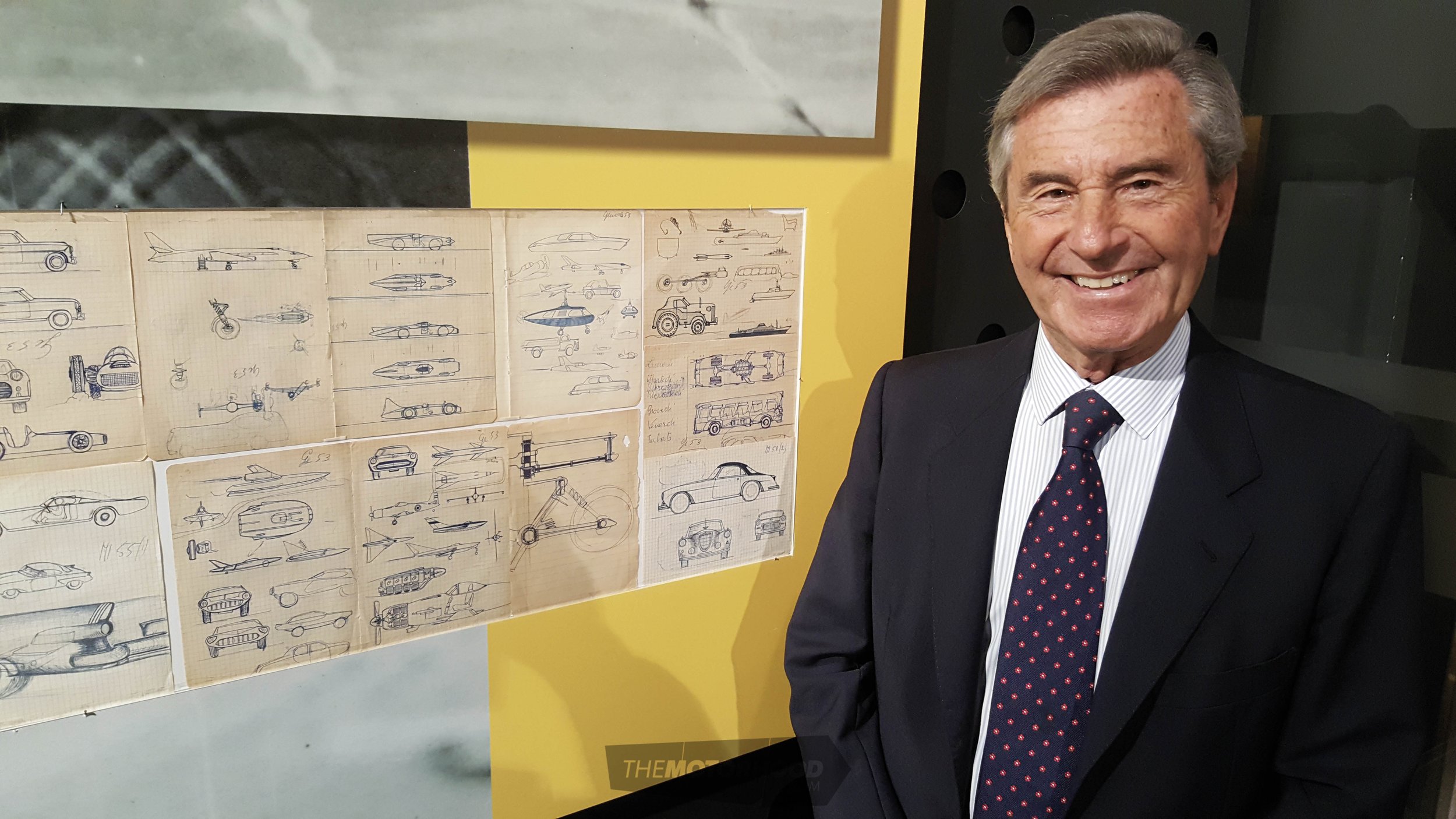

In researching this piece, I found out that the creator of this most durable design, Leonardo Fioravanti, is now in his 80s, yet still active via his design house in Turin. I decided to ask him the question. To my surprise and delight, he answered.

Dear Mr. Adshead,

Thank you for your gentle words on my design. You can find the history of my projects on a book that I wrote few years ago: “Il Cavallino nel Cuore” Giorgio Nada Editore, in English version, too. In particular, the two circular tail lights I began to define with Dino 206 GT, Turin Motor Show 1967, because this is the minimum geometrical and optical way to respect the homologation requirements. Simple and original, I like it till now.

Best Regards, Leonardo Fioravanti

Not only has this pure aesthetic shone brightly through fifty years of cutting-edge design, but even the lighting units themselves remained virtually the same from the 1970s right through to 2011 — from the first 308 and 365 designs, through the later 288 GTO, F40 (all by Fioravanti), and then the 360 and 550 models, all the way through to the 612. The 430 and Enzo then continued the theme with a new semi-exposed version.

The Return of the Twin

In 2008, Ferrari reintroduced the California name, and with it single circular rear light units. They were then replicated across the range, a pattern that persisted for a period of 11 years. Then, in 2017, the GT4C Lusso replaced the FF, and pairs of twin circular tail lights made a welcome return, and they were cemented in place for years to come by the 812 Superfast.

Pairs of single circular tail lights have also been in favour at various times for Ferrari designers, as have pairs of triple circular tail lights. Think 1960s Superamericas, and the 365 GTC4, and, of course, there were the horizontal strakes of the 1980s Testarossa and 348. The rightness of the pairs of twin circular tail lights has made them by far the most durable and defining Ferrari design element.

They have also endured beyond Pininfarina’s tenure as Ferrari’s most favoured design house, so it’s clear that Fioravanti’s creation has been adopted as Ferrari’s own, and they continue to adorn the latest in-house designs. It remains to be seen how many of these shapes will stand the test of time as well as those of that most famous and prolific Italian design house.

Ferraris’ front-end designs have varied far more, driven by the need to accommodate ever more rigorous safety regulations and aerodynamics, as well as both front and rear mid-engined layouts. There have been attempts to create a consistent front end look across the range at various points in the last fifty years, but even just considering headlights, let alone the endless permutations possible when designing a car’s face, nothing matches the simple elegance and the emotional connection inspired by matching pairs of circular lights and tailpipes. They are both instantly identifiable and remarkable.

That unmistakeable combination also binds together Ferraris from multiple generations. I once took part in a convoy of Ferraris travelling down the length of the North Island, which included a Daytona, 355, 550, and 612, spanning over 40 years of the theme. All that was missing at that time, to bring it bang up to date, was an 812 Superfast, but in convoy that dual signature was powerfully underlined.

It will be interesting to see what comes next. The current range utilises pairs of both single tail lights and twin tail lights on both V8s and V12s, which is four different combinations across a range of five basic car designs. This range of treatments is perhaps indicative of the current challenges facing Ferrari’s designers. The factory cites bringing design in-house as being necessary to be able to integrate the potentially conflicting demands of safety, aerodynamic efficiency, and performance, which now includes hybrid power, into a factory form. We can only hope they find a way forward that will recapture something of the timeless appeal of Leonardo’s genius.

Pininfarina Prodigy

Leonardo Fioravanti’s legacy is not just in lights and tail pipes. How many other car designers can lay claim to so many beautiful and iconic car designs, let alone Ferrari designs?

Leonardo’s hitlist:

– Dino 206/246

– Ferrari Daytona

– Ferrari F40

– Ferrari 348

– Ferrari P5 show car

– Ferrari P6 show car

– Ferrari Pinin

– Ferrari 512 Berlinetta Boxer

– Ferrari 365 GT4 2+2 (the forerunner of the Ferrari 400)

– Ferrari 308 GTB

– Ferrari 288 GTO

When you look at that list, it is quite staggering that his name is not as immediately recognisable as that of his illustrious employer. That prompted me to do a little desk research, which revealed some interesting facts.

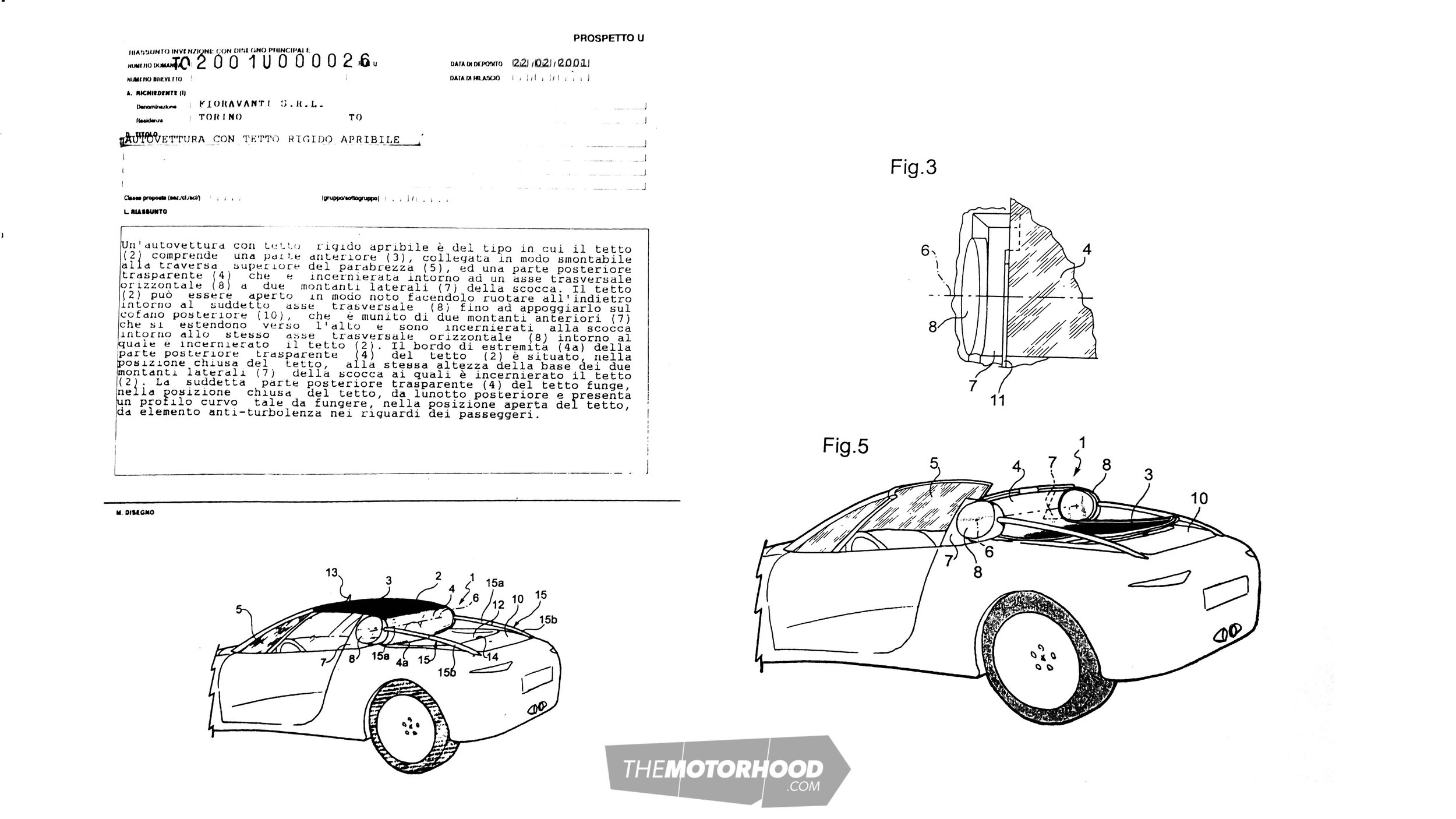

Fioravanti joined Pininfarina from the Politecnico di Milano in 1964, at age 26, as a stylist. He remained with Pininfarina for 24 years in various positions before becoming design director at Alfa Romeo Centro Stile and deputy General Manager of Ferrari. He then set up his own design house, Fioravanti Srl, in 1991. That company developed the Ferrari fan favourite, the pivoting carbon-fibre and photochromic-glass roof, the ‘Revochromico’, fitted to the 575M Superamerica. It rotated around a spindle on the rear roof pillars to lie upside down on the engine cover.

Probably the story that best encapsulates his design genius and the introduction of his lighting legacy is his single-handed conception and design of the Daytona.

The story goes that he saw a couple of undressed 275 GTB chassis in the factory with V12 engines. He was inspired to produce a 1:1 model to sit on such a chassis to demonstrate his latest ideas. The 275 GTB had only just been launched in 1965, but his model was shown to Enzo Ferrari. Il Commandatore liked what he saw so much that, after suggesting Fioravanti add a little to the track at each end, he gave it the seal of approval, and the Daytona was born.

Roger Adshead didn’t give up there. He got to meet the great man in person, and his delightful and insightful interview with one of the greatest car designers of our age – who really deserves to be better known in the English speaking world – Leonardo Fioravanti, will be available to read back on The Motorhood next Friday.

This article originally appeared in New Zealand Classic Car issue No. 370