TALK TO THE MECHANICS

Michael Clark catches up for a long-awaited, one-on-one lunch with Rangiora’s Brabham F1 team chief mechanic, Cary Taylor

By Michael Clark

Many years ago — in June 1995 to be more precise — I was being wowed with yet another terrific tale from Geoff Manning who had worked spanners on all types of racing cars. We were chatting at Bruce McLaren Intermediate school on the 25th anniversary of the death of the extraordinary Kiwi for whom the school was named. Geoff, who had been part of Ford’s Le Mans programme in the ’60s, and also Graham Hill’s chief mechanic — clearly realising that he had me in the palm of his hand — offered a piece of advice that I’ve never forgotten: “If you want the really good stories, talk to the mechanics.”

Without doubt the top mechanics, those involved in the highest echelons of motor racing, have stories galore — after all, they had relationships with their drivers so intimate that, to quote Geoff all those years ago, “Mechanics know what really happened.”

Rangiora’s Cary Taylor has long been on my radar for ‘Lunch with’ but distance has been the barrier. However, in December 2020 we finally got a chance to sit down. Cary has suggested Untouched World Kitchen near Christchurch Airport and it proves an excellent choice — absolutely worth a visit. I’ve got to know Cary over the years and have interviewed him in front of audiences at dinners for both Bruce McLaren and Denny Hulme, but always as part of a panel with other notables from our rich motor racing history. Consequently, never before have I had a chance for a decent one-on-one and right from the get-go I find myself discovering new and fascinating information.

Rubbing shoulders

Cary and his older brother Ian had an early indoctrination into the sport via their enthusiastic father, with the annual visit to Wigram. On leaving school Cary started an engineering apprenticeship in a repair and recovery automotive shop, where he found himself rubbing shoulders with some of Canterbury’s finest: “… Frank Shuter, Ronnie Moore, Ron Rutherford, Harold Heasley — I was sucked into it”.

In 1964 Ian and Cary left for Europe — “We’d been reading about the famous tracks for some time so decided to go and have a look. We started at Monaco then headed to Spa for the Belgian GP before going to Le Mans.”

Cary took with him a letter from the mayor of Rangiora, which stated Cary was a fine, upstanding lad, and it helped him land a job at Dove Motors in Woking, not far from the still relatively young Brabham works.

“It was always my intention to become involved with motor racing while we were there,” Cary tells me.

What staggered me was that, when Cary got the job at Brabham Conversions, it was the first time he’d had exposure to purpose-built racing cars! Less than five years had elapsed since the partnership of Jack Brabham and Ron Tauranac had been formalised. In F2 and F3 the Tauranac-designed Brabhams were already well established as soundly engineered cars, ideal for the privateer. However, F1 success was limited at a time when Lotus, BRM, and Ferrari were doing most of the winning.

Can-do reputation

In his autobiography To Finish First, Kiwi Phil Kerr, at that time Jack’s right-hand man at Brabham, wrote that the main workshop had “two highly qualified mechanics, Bob Ilich from Perth, Western Australia, and Cary Taylor from New Zealand [who] were more than keen to go racing, and were considering joining one of the other established racing teams. However, during 1965 I assured them that an opportunity to go Formula 1 racing with Brabham was imminent”.

Cary confirms that he’d made his intentions clear to Phil, and those didn’t include staying in the factory assembling production racing cars.

Cary recalls, “Tauranac always liked Kiwi mechanics because we had a can-do reputation — we had to make do and repair, which is exactly what is needed at the track.”

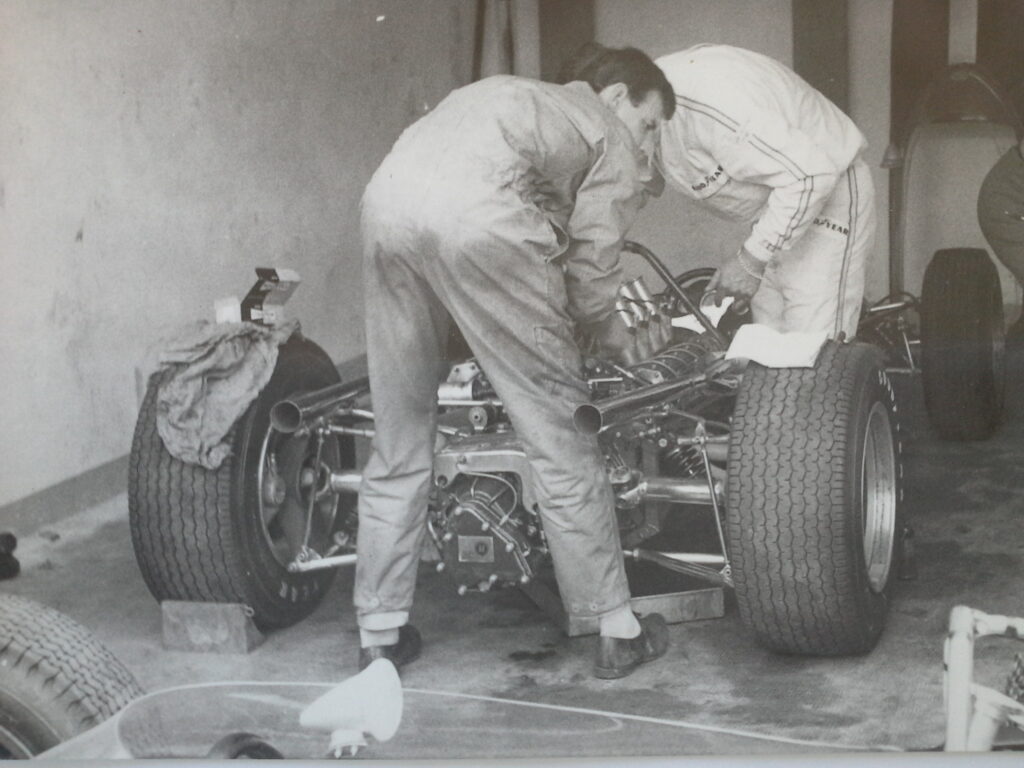

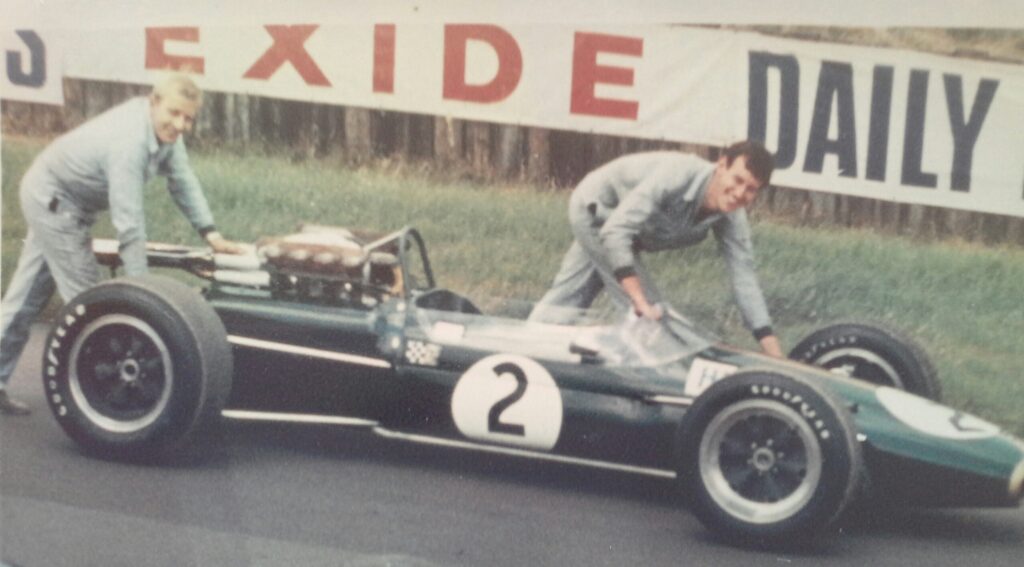

F1 was about to change, with the maximum capacity doubling to three litres from the start of 1966. As teams scrambled for engines, Brabham had entered into an arrangement with Repco in Australia for a lightweight Oldsmobile-based V8 that would be low on power but where reliability was their hoped-for ace. This environment when Cary not only entered F1 but came in as an ‘in the field’ race mechanic.

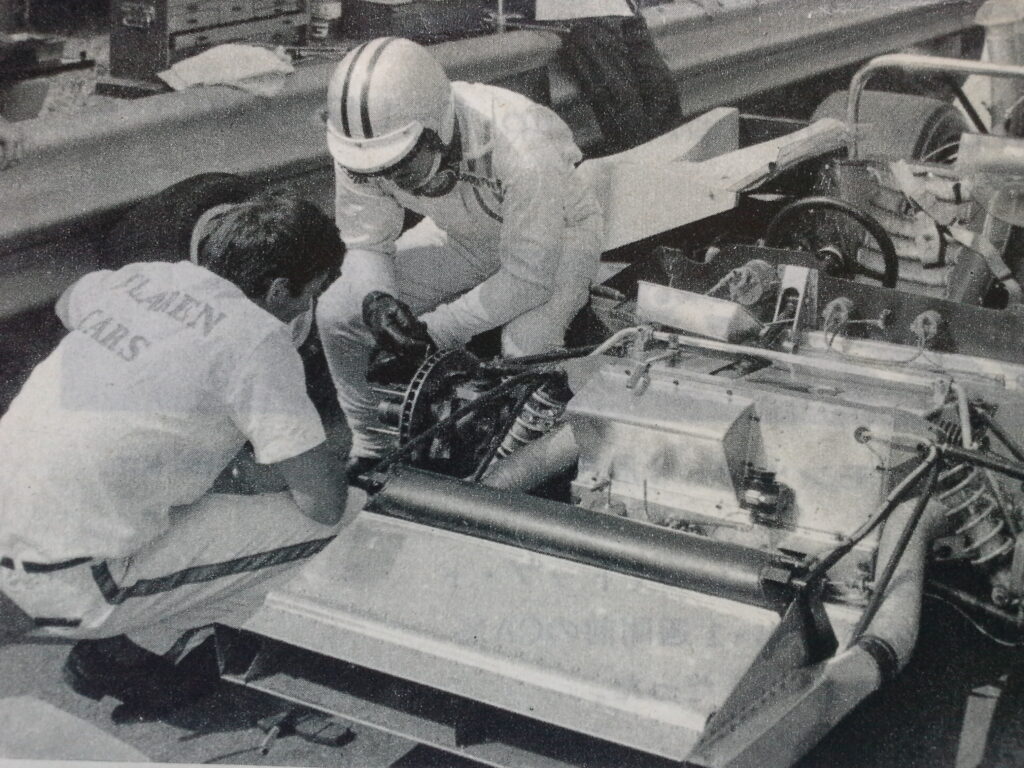

“In 1966 we had four mechanics for the two cars. [Fellow Kiwi] Roy Billington was the head man, Bob Ilich was in charge of the engines, Hughie Absalom —later replaced by John Muller, another Kiwi — and me.”

From the start, Cary was chief mechanic on his countryman’s car. For a tiny and still newish F1 team, it was an extraordinarily successful season, with Brabham winning the constructors’ championship and Jack himself taking his third world title.

As Cary recalls, “We weren’t just mechanics; we were the transporter drivers, logistics guys, we looked after engines, chassis — it was hard work.”

Quite a year

Cary then debunks the notion that the reliability of those championship-winning Repcos were the key to Brabham’s success.

“It was tough because the engines were coming from Australia — honestly, without Araldite those Repcos would never have hung together.”

Despite the multitasking and the long hours, I wondered if there was time for celebrating the successes.

“Socialising was very rare — but I do remember some very sore heads after Jack had won the French Grand Prix at Reims because the winner got 100 bottles of champagne. Not only was it the first win in F1 for a driver/constructor, it was also Jack’s first win in six years!”

That year, 1966, had been quite a year for Cary, having gone from having never laid spanners on a racing car outside a factory to being part of the world championship-winning team — and a tiny team at that.

Cary remembers how much “Tauranac and Brabham relied on us guys” — which, given that they were only four of them for two cars, seems like a massive understatement. When you contrast that with the number of race engineers and technicians that F1 teams would be taking to races in years to come, the role of the mechanics in such a small organisation takes on an even greater degree of significance.

Extremely challenging

In the two years — 1966 and 1967 — that Cary worked for the Brabham F1 team, it won two world drivers’ titles, two constructors’ titles, and achieved eight wins from twenty championship races.

Over that same period, Lotus won five, and Ferrari, which had started 1966 as the clear favourite, had only two wins. In addition, the Brabham team won four non-championship races at a time when no other two-car team had as few personnel. There was often no time for relaxing between races.

“The South African Grand Prix was held on 2 January 1967 at Kyalami just outside of Johannesburg,” Carl tells me, “and five days later we were at Pukekohe for the New Zealand Grand Prix. I flew to Auckland with a brown paper bag stuffed full of South African rand with my tools as hand luggage.”

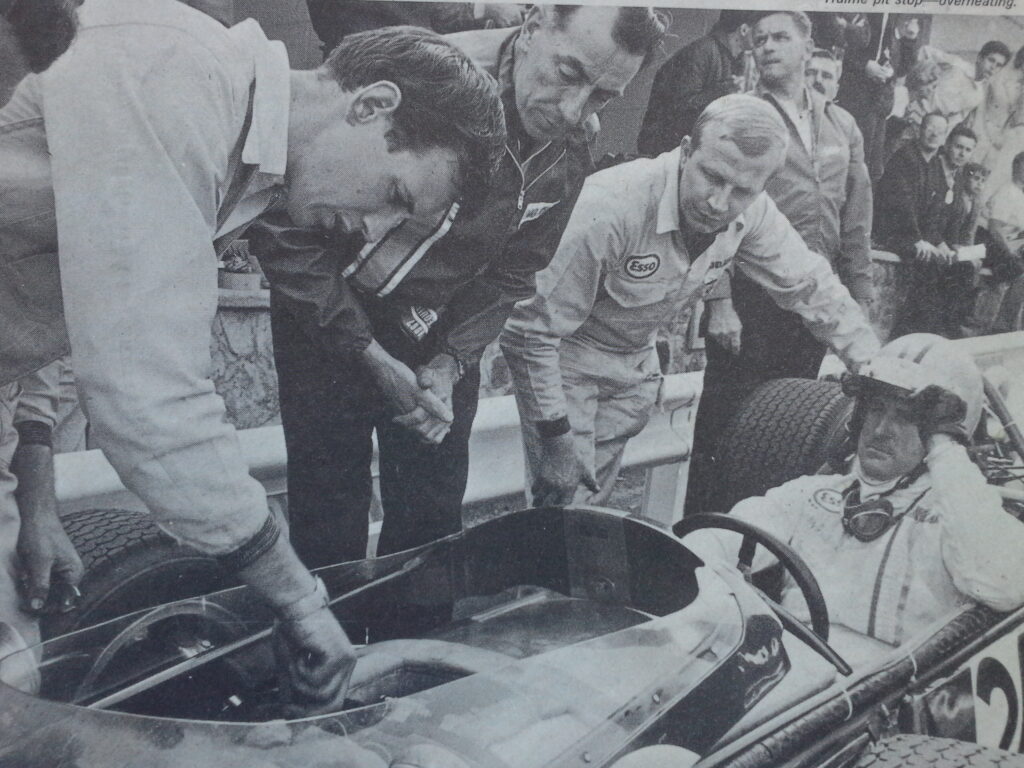

Denny Hulme’s world championship in 1967 came on the back of wins at two of the toughest events: Monaco and the German Grand Prix at the Nürburgring — ‘the Green Hell’.

Winning around the streets of Monte Carlo is a top priority for most F1 drivers, what with all the ceremony that goes with it, but given the accident involving Ferrari driver Lorenzo Bandini late in the race — sadly, he died a few days later — Cary recalls that “Denny got almost no recognition because the post-race celebrations were cancelled”.

As for Denny’s victory at ‘the Ring’ — “That was extremely challenging, testimony to him and our car preparation.”

Jack Brabham summed up his team’s achievements in his autobiography: “Given the chance, I’d race with them all tomorrow.”

What next?

Cary’s parents were both killed in January 1968, and he returned to Rangiora, uncertain as to what he would do next. Returning to Brabham didn’t feature in his plans, nor in the plans of his former teammate and Formula One world champion, Denny Hulme. “Denny had already been driving for McLaren’s in Can-Am during ’67, and when Bruce expanded his F1 team for 1968, Denny left Brabham and joined Bruce.” Cary went to Wigram to catch up with Denny. “I found him sitting in a tent chatting to Bruce. Denny introduced me to him, and after telling him I’d been his mechanic at Brabham’s, he was then very keen to find out what my plans were.

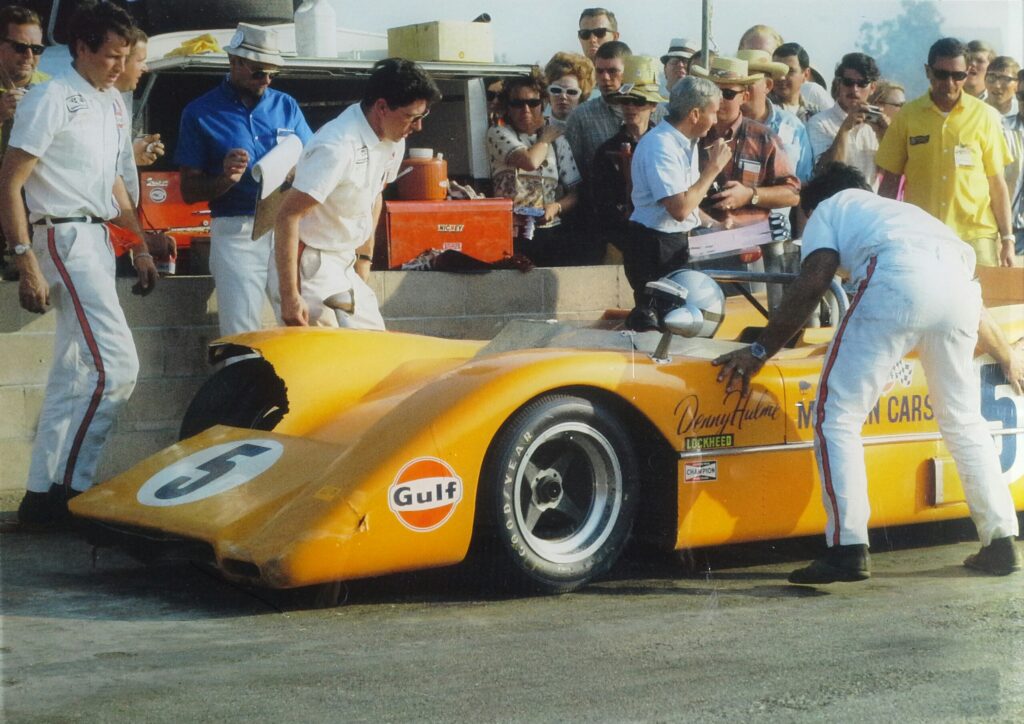

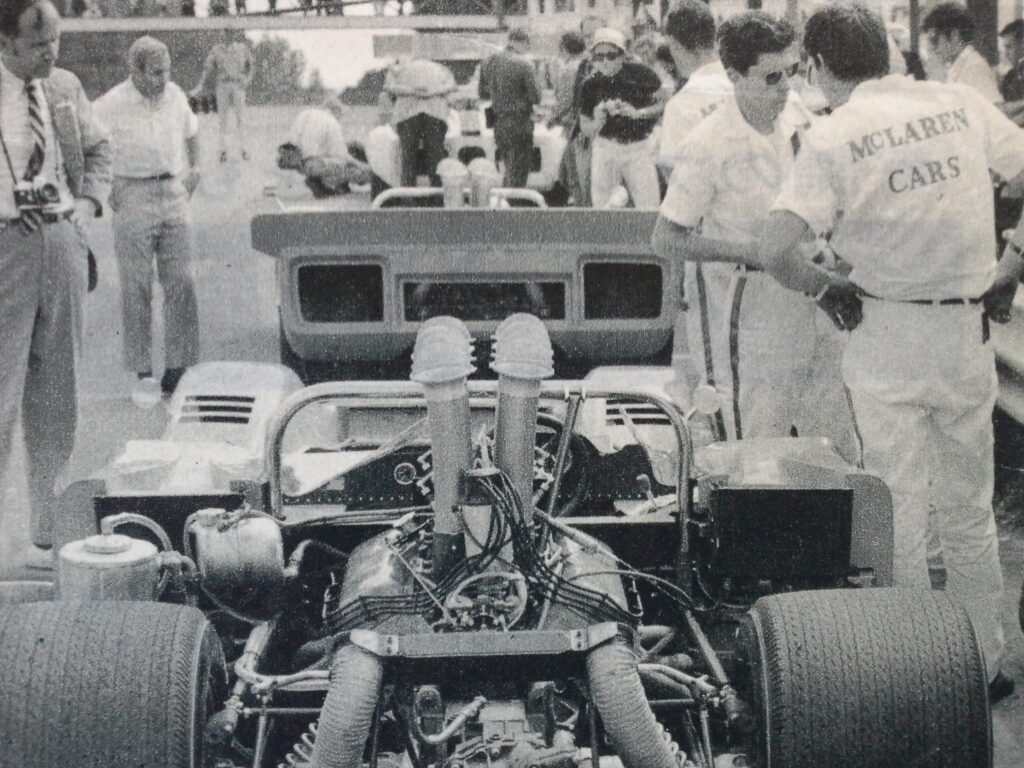

I told him my intention was to return to the UK later in the year to continue in motor racing. The outcome of this discussion was the invitation to join McLaren’s Can-Am team as chief engineer on Denny’s car.” That gave Cary a little more time in New Zealand before heading to Boston to start his new life with McLaren. The rich six-race Can-Am championship kicked off at Road America in Wisconsin on the first of September and concluded in Las Vegas ten weeks later. A trip to Edmonton in between was the only round that season north of the border.

Two for two

Cary well recalls Denny’s approach. “When everything was going well, it was his car. When it wasn’t, it was my problem to fix.” Cary kept the problems to a minimum ,which meant Denny became 1968 Can-Am champion, winning half of the six rounds. The legendary historian Doug Nye wrote in his McLaren book, “Six mechanics would travel with the team: three from the engine division in California and three from Colnbrook, including Tyler (Alexander) and Cary Taylor, who had been Denny’s chief mechanic with Brabham the previous year.’ For the second time running, a Denny-driven car expertly prepared by Cary had prevailed in a major championship.

At the end of the Can-Am campaign, Cary flew back to New Zealand, having made a commitment to be back in England by Easter to oversee the assembly once the tub was finished. “The amount of testing was quite phenomenal.” It paid off. The number of rounds had nearly doubled to eleven for the 1969 version of the Canadian-American Challenge Cup, but all that preparation meant the papaya-coloured McLarens won every race. Bruce was crowned champion ahead of Denny but that season had opened Cary’s eyes to the other end of motorsport. “Bruce let me do some testing of the M8B — I’d never been on a track before, and now I had a big-block Chev with over 650 horsepower behind me. It shows what sort of a guy he was … ”

In the driving seat

An odd series of circumstances led to him buying his own racing car. “Bruce had crashed at Riverside, and there was one race to go. I trailered it from Los Angeles to Boston in four or five days and then put it on a plane to the factory.” It was while back in England that Cary encountered fellow Cantabrian Bert Hawthorne, a racing mechanic who was evolving into a pretty handy racing driver, who had been running his own Brabham in New Zealand. “We met up in a pub, and I ended up buying a racing car — that Can-Am experience had wet my whistle!” The Brabham BT21 was powered by a twin-cam Ford, and initially Cary did local races back in New Zealand over the summer of 1969–70. “It was something I could manage, and I was happy with the car — if I was going to have a go, then I wanted it to be in a good car.”

Cary was back at McLaren HQ by the spring of 1970 for the next assault on the lucrative Can-Am championship. Denny had burnt his hands at Indy, which meant that on 2 June it was Bruce who was testing his teammate’s car at Goodwood. Cary wasn’t just there as a mechanic; he was doing installation laps in the M8D Can-Am car while “Bruce was buzzing around in the M14,” McLaren’s new F1 challenger. “I was supposed to be just trundling around but managed to spin it coming out of the chicane … ” The tragic events of later that day are still raw half a century on.

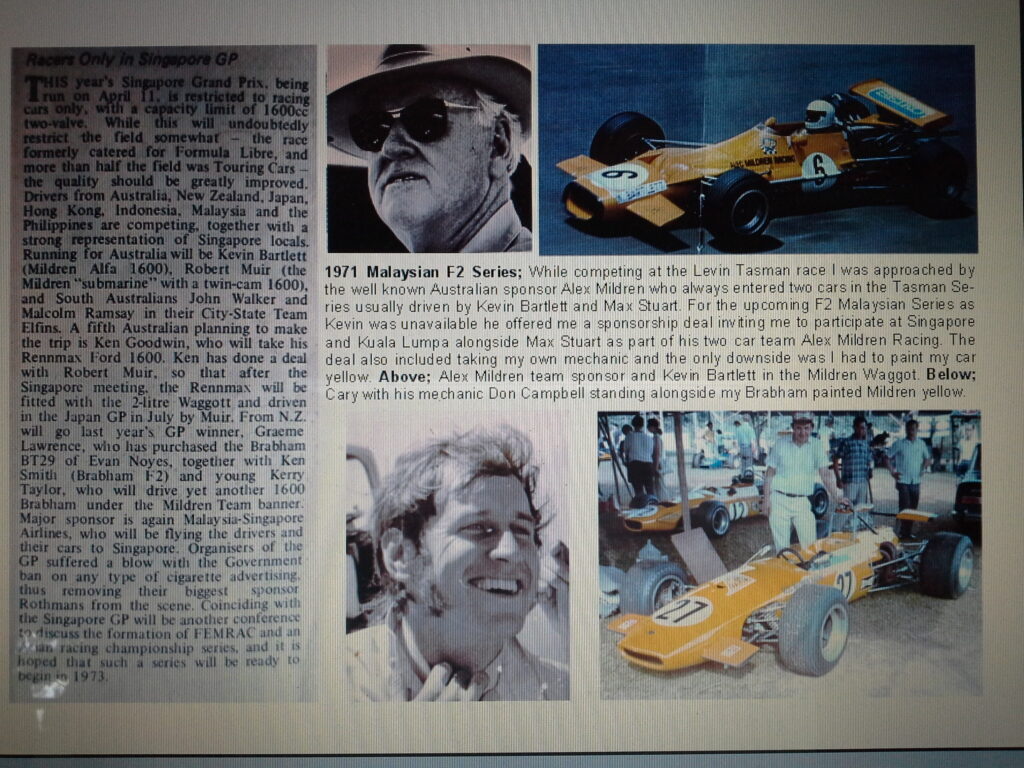

We move back to ‘Cary the racing driver’ when he planned to do the New Zealand rounds of the 1971 Tasman Series. “I vividly recall the driver’s briefing ahead of round one at Levin where (Graham) McRae made it very clear to those of us with slower cars what he’d do if we got in his way while he was lapping us.”

Nice to see you, too

Not only did he avoid annoying McRae, his drive at Levin attracted the attention of the evergreen Australian entrant Alec Mildren, who approached Cary with an offer he couldn’t refuse. “He’d pay to fly me, my car, and mechanic Don Campbell, who designed and built my fuel-injection head, up to South-East Asia for the two races — one at Singapore and the other at Kuala Lumpur. I had to get the car to Sydney where Alec would provide a mechanic. The only negative was that the car had to be spray painted ‘Mildren yellow’. It’s clear from Cary’s facial expression that my favourite colour for a racing car is not his.

“Singapore was unbelievably dangerous, with monsoon drains at the edge of the circuit.” Dropping the flag to start the race was none other than his old boss, Jack Brabham. He greeted his former mechanic turned racing driver with, “What the hell are you doing here?” Cary did a good job to finish fifth, as two of the cars in front, including that of winner Graeme Lawrence, had considerably more powerful engines. That opened his eyes to the possibilities, especially after finishing sixth the following weekend in the Selangor GP. “Overall, I was thrilled to have finished ahead of most of the hotshot Australian drivers. I felt I hadn’t let the Mildren team down.” The plan was to sell the car and buy another one with a four-valve motor, “but it never happened because the market for twin-cam cars had evaporated.”

Although not planning to return to the Northern Hemisphere in 1971, something there still called him: his toolbox. By then he’d met his future wife, Laraine. He built some flats, and his priorities changed — or so he thought. “I decided to take Laraine on an OE to Europe to see what the McLaren boys were up to — and to pick up my tool box.”

Back on the tools

Unsurprisingly, Phil Kerr wasn’t about to let someone with Cary’s skills float away so easily, and he was quickly put in charge of the Yardley-sponsored McLaren that would be piloted by Mike Hailwood, winner of multiple motorcycle championships. Cary has fond memories. “What a wonderful, non-serious guy — always open to suggestions and a very competent driver. He was generally a contender around fourth or fifth. The Nürburgring crash was a sad end to Mike’s F1 aspirations. I’ve still got the Heuer watch he gave me.” Legendary Kiwi Formula Ford wizard Graeme Cook was part of the Yardley team that 1974 season and recalls Laraine’s pivotal importance to the team. “She was in the catering division. She fitted in so well in what was a pretty tough season, especially after Hailwood’s crash. Between her and Cary, they pretty much kept the team together.” The world of F1 had changed since Cary had left F1 at the end of 1967, and he found sponsorship “ … a little off-putting. I remember at Monaco we were trying to get the car ready only to be told it was required for a dolly-bird shoot.”

At the end of 1974, McLaren was downsizing. Without the Yardley sponsorship, fewer people would be needed, so Laraine and Cary decided to come home for good. “Britain was not a good place to be what with the fuel shock, the IRA, and the prospect of a winter under those conditions. I didn’t want to stay on in front of guys who had families to support, so we came home.”

Today the Taylors are on a lifestyle block in Rangiora, and Cary is as lean today as he was when racing a yellow Brabham in Malaysia. When they returned, he initially worked as a tool room engineer in nearby Kaiapoi but “I didn’t want to be in overalls forever and a day, so I answered an advertisement for a sales rep.” He never looked back.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about chatting about Cary’s life is how unremarkable the man himself sees it all. But there was clearly something that Brabham and Tauranac saw in him when he was elevated from shop-floor to the F1 Brabham team. And you can’t imagine Bruce invited too many mechanics to head out strapped on top of a monstrous Can-Am car. Clearly there was something special.

Perhaps most remarkable of all is the fact that from 1966 to 1970, every team Cary worked on won major championships. Now that’s special.