Lunch with Boost

Roger Bailey is one of the near legendary engineers who have a habit of preparing race-winning cars and he became close and lifelong friends with many of the Kiwis who dominated the golden era of top-flight motorsport

By Michael Clark

It was while in Gisborne in December 2015 that my phone went, displaying a great number of digits. A warm English voice introduced himself but there was no need — we’d met, albeit only briefly, a few years earlier when Roger Bailey and I had shaken hands. Roger had been given my number on the basis that I may be able to provide a recent health update on our mutual friend Chris Amon. Despite the brevity of our one and only meeting in January 2011 when Roger had come to New Zealand for the Chris Amon Festival, I already felt as if I knew him. Stories about him always flowed freely from Chris, Howden Ganley, Wally Willmott, Eoin Young, and others. After I told Roger what I knew he said, “Would you mind if I called occasionally to see how my old mate is getting on?”

By ‘occasionally’, Roger meant every fortnight or so and after Chris died in August 2016 he said he’d stay in touch — and for more than five years not a month has gone by without his familiar greeting, “How are things in Kiwiland?” This being Indy 500 month, it seemed the logical time for a book on Roger’s life to be launched and seeing as he’s attending his 51st race at the Brickyard, Indiana’s capital is the logical venue.

The Boost gauge

Roger’s story is a classic illustration of what hard work, honesty to the point of brutal frankness, a ‘can-do’ approach, and a racer’s brain can get you in this sport of car racing. Roger, or ‘Boost’ as he’s known up and down the pitlanes of America, was who Kenny Smith turned to when he was dragging a reluctant teenager around the different pit garages at Laguna Seca.

“Scott [Dixon] kept complaining that it was too hot and he just wanted to go back to the hotel pool. I had to tell him that I was trying to secure his future — we weren’t getting much of a look in until we saw Roger who knew everyone and set about introducing Scott as New Zealand’s next big thing.” Some people could say that and it would sound like a PR spin but, as Kenny recalled, “Roger had such respect by everyone in Indycar so when he said something, people took notice.”

Although he’s spent close to two-thirds of his life in America, Roger hails from the English Midlands and has never lost either his pleasant accent, or his powerful voice. “I started off working in a local garage while I was studying at Peterborough Technical College but by 1959, by which time I was 18, I started helping Jim Russell at his driving school at Snetterton.”

That was Roger’s first job in racing and he never stopped until he retired. “Russell offered me a position working on the school cars but that didn’t interest me, so I started building Jaguar racing engines for Don Moore, which was a great experience.” It was about this time that Formula Junior was erupting with Ford leading the way, and BMC was anxious to get involved.

“Don had good contacts with BMC, and remember, the Mini had just come out. He’d been building racing versions of the Mini’s 850 and so the FJ version was basically the same motor but 150cc bigger.”

Country life

Sir John Whitmore won the 1961 British Saloon Car Championship in a Mini and because he was a customer of Moore’s, doors were opened for Roger. “Sir John often invited me to be a house guest at Orsett Hall on weekends when we weren’t motor racing. Jim Clark and Graham Hill were regular guests too and the times I spent on the estate were great; I’ll never forget them.”

It was Whitmore who introduced Roger to John Cooper. “He offered me a job on the new works Mini-Cooper team but after only a few weeks he told me I was joining Ken Tyrrell’s outfit. I worked for Tyrrell for three years preparing Minis and the BMC powered Coopers.” The relationship culminated with Roger spannering the winning car in the new British F3 championship. “I got introduced to this little Scottish bloke and was told I’d be looking after his car. He won 12 out of 14 races and I still have the watch Jackie [Stewart] gave me engraved with ‘Thanks for 1964’.”

The first of the famous Kiwis that Roger got to know was Denny Hulme. “The Bear would sometimes drive a third car for Tyrrell when he wasn’t doing his own thing.” But Formula 1 was calling Roger with another Kiwi encounter. “I was Bruce’s mechanic for the last two races he drove for Cooper at the end of ’65 — Watkins Glen and Mexico. In those days we just had two mechanics taking care of two cars. I was assigned to Bruce but for 1966 he was off to drive his first McLaren F1 car.”

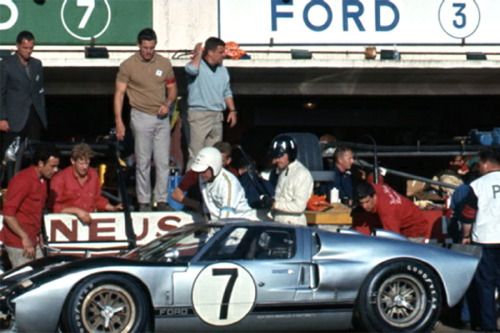

Roger’s next stop was at Alan Mann Racing, the organisation that ran factory-backed Fords in the British Touring Car Championship, but more significantly for 1966, Ford’s attack on Le Mans. “They sent me to LA in February ’66 — Shelby’s workshop on Imperial Highway. There were half a dozen or so of us from Alan Mann’s shop and a similar number from Holman-Moody. When you add the Shelby guys there were quite a few of us working in this old North American Aviation building. Collectively we built seven Mk2 GT40s — which of course you Kiwis won!”

America calling

By this time Roger had moved into a sprawling house in London’s leafy south-western suburbs. “There were some Cooper mechanics, Mike Hailwood, Peter Revson, and Christopher … I got the bedroom next to Amon and we became good friends. In the early part of 1967 Chris told me one day that he was going to drive for Penske in America. Believe it or not, our phone calls used to go to the local pub and one day we were there for Sunday lunch and there was a phone call for Amon. I answered it and this voice told me he was Roger Penske looking for Chris. I told him he wasn’t there and he said ‘Amon’s going to do the Can-Am for me. Why don’t you come and look after his car?’ I was earning good money with Ford but out of curiosity I asked him ‘What are you paying?’ and he told me a number for a week that I wasn’t earning in a month at Alan Mann. So I said I’ll think about it. The following Thursday I received a ticket by registered mail from Philadelphia with a note from Penske — ‘I hope you’ve made your mind up. See you Sunday. Roger.’ So that was that.”

Roger’s initial relocation to the States was short lived. “Chris by now was doing F1 and sports cars for Ferrari and phoned to apologise for taking that drive instead of Penske but I ended up having a great season on George Follmer’s Can-Am Lola.” But Chris hadn’t forgotten about his old flatmate.

A Ferrari first

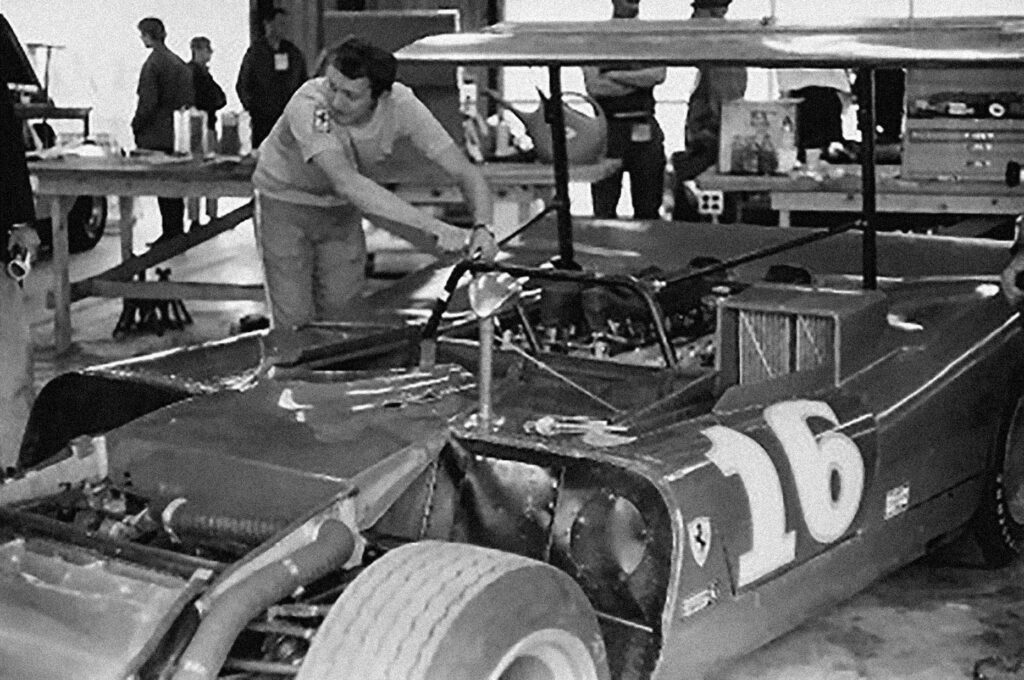

“He phoned and said Ferrari were going to send a car to New Zealand for the Tasman Series and that they wanted an English-speaking mechanic. I’d just had a great summer spannering the car Chris was supposed to drive and now I was about to become the first non-Italian mechanic on a works’ Ferrari — again thanks to Chrissy.”

Roger’s recall is astonishing. He still remembers the names of pubs in Levin, Christchurch, and Invercargill and Hunterville which is where he met ‘the guy’. “I flew to Milan in September ’67, Chris picked me up and we went straight to Ferrari. I met Mauro Forghieri and the other guys that I’d be building the car with. Chris kept telling me I’d be working with his old mechanic from when he had the Maserati 250F.”

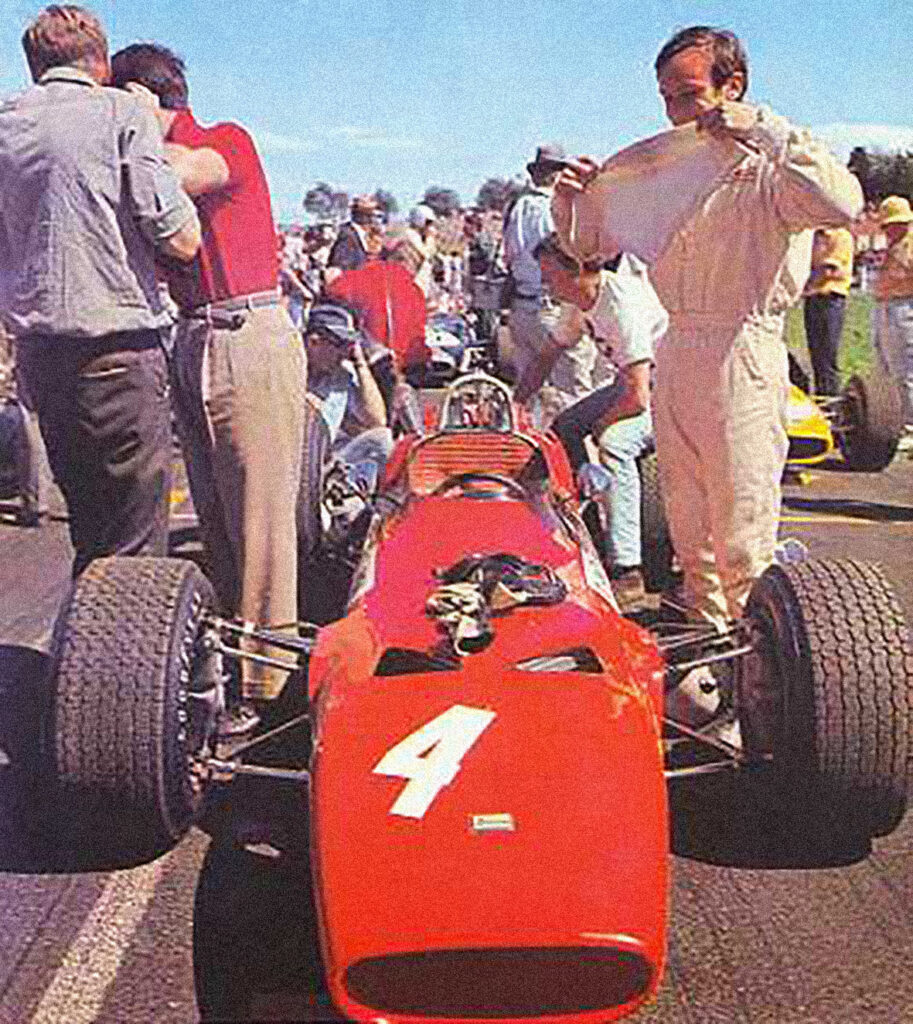

‘The guy’ Chris was talking about was Bruce Wilson, from Hunterville. The two of them proved to be a powerful combination for the young Kiwi in a championship that pitted ‘the trio at the top’ against Jim Clark and — for the Australian races — Graham Hill, Roger’s old mates from days on a country estate only a few years earlier.

Even before Roger arrived in New Zealand for the 1968 Tasman series, Chris Amon had told him about Bruce Wilson, the ace spannerman from Hunterville who’d fettled the young farmer’s Maserati 250F in the early ’60s. On the passing of the legendary mechanic, Roger penned a wonderful tribute for the service with a constant reference to ‘the guy’ — the guy Amon eulogised over and who, with Roger, went one better than their 1968 runner-up position to Jimmy Clark when the Ferrari driver was crowned champion.

The first non-Italian to become a full-time mechanic for the works team, Roger was loving life in Italy. “I can’t even begin to explain what it was like to be there in those days and work under the ‘Old Man’. You can read all the books, but, unless you were there, you can’t imagine. He was so respected, and it was an experience I’ll never forget.”

Watch and learn

After Amon won half of the eight Tasman races in ’69 en route to the title, the team were invited to lunch with ‘Il Commendatore’ back at Maranello.

“He got up and gave us a big hug and a handshake, then he put his hand in his pocket and brought out a gold watch — that he gave to me! Chris got a handshake and I got a watch with a little black prancing horse on the dial. It’s one of those things that to me is priceless.”

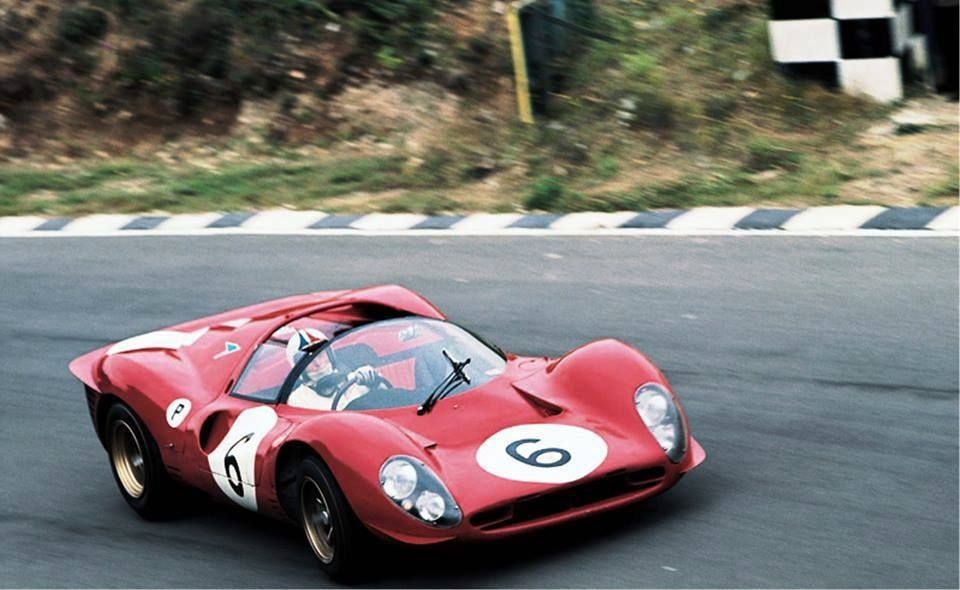

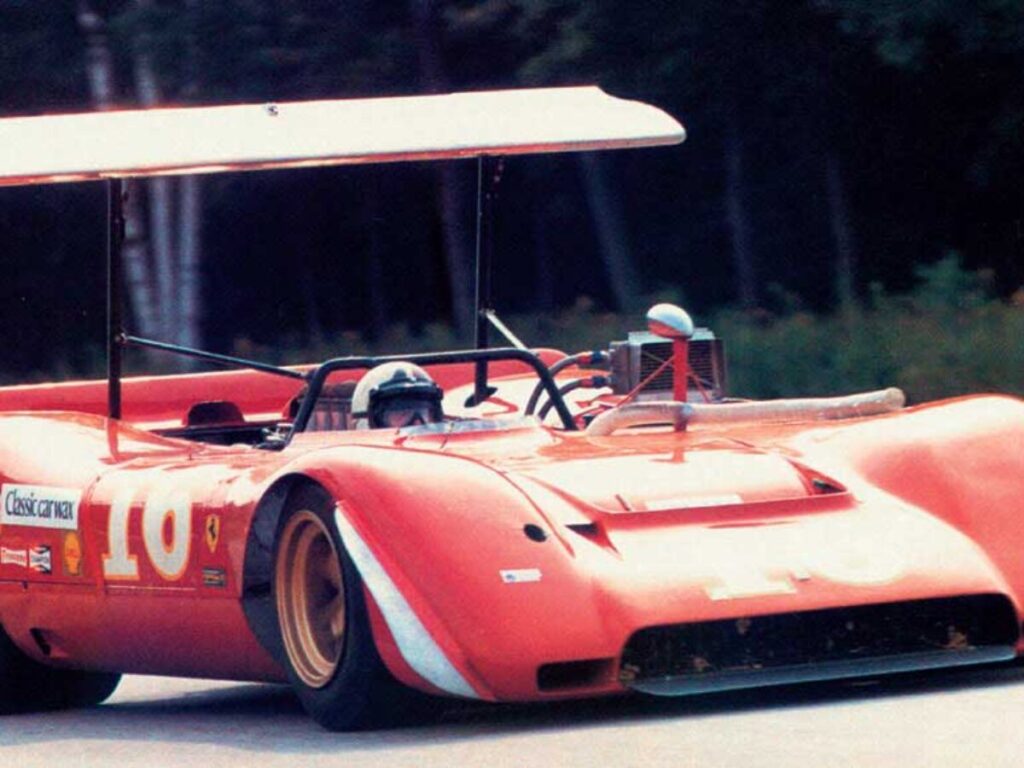

Roger was then sent to America to run the massive Ferrari Can-Am car.

“It started out as a 6.3 V12 but grew to 6.9 litres — the biggest engine they’ve ever built. It was a beast.”

After driving the McLaren, Chris declared that the Italians had built the superior chassis: “I’d love to have had one of their Chevs in the back on the Ferrari.”

Despite Kiwi team manager Bill Gavin confirming that 1969 was the most stressful year of his life, Roger recalls it as “probably the most enjoyable time of my 50-plus years in racing. In fact, those two and half years with Ferrari, and Chrissie, were the best of my racing life.

“Chris won Daytona with [Lorenzo] Bandini before I was there. In F1 Chris led a lot of races that we should have won. I’m sure your readers are smart enough to know — but just in case anyone was wondering — Chris was not a car breaker. All those GP wins that were snatched away in ’68 — Spain, Spa, Canada — none of those retirements was down to Amon. Ferrari failed him — he should have been world champion that year. Who knows where his career would have gone from there, but I doubt it would have been the only world title.”

Forsaking Ferrari

Roger had greater insight than anyone as to the frustrations his mate was having with the unreliability of Ferrari’s venerable V12 in F1.

“Chris was getting despondent; I think seven of the new flat-12s blew up on the dyno. We were sharing a flat in Modena and one day he told me he was going to join the new March team for 1970. That started well but, just about the time the March ran out of development, the Ferraris came right — it was just bad timing on Chris’s part.”

The mechanical maestro reflects on the only wins he had during his time with the Scuderia.

“We were second in the ’67 BOAC 500 with a P4 when he had my old F3 charge Jackie [Stewart] as his co-driver, second in the British GP in ’68, a second at Edmonton in the Can-Am, and he and Mario [Andretti] had a second at Sebring. The only wins we got were with the Tasman cars out there in ’68 and ’69.”

On leaving Ferrari Roger was also offered a role at March but wasn’t interested, so he built a couple of BRM Can-Am cars that were later driven by Howden Ganley — “Everywhere I went I seemed to make friends with Kiwis.” They’re still close today, and, when Roger makes his monthly phone call, he invariably asks, “Have you heard from Mr Ganley lately? Where is he these days — I can never keep up with him.”

That connection continued into Roger’s next post: building Can-Am (Chev big-blocks) and Indy (Offenhausers) for McLaren.

“I was with McLaren for 10 years in Detroit; we had some fun times. I built for Offys for [Peter] Revson, the Bear [Denny Hulme], and Lone Star JR [Johnny Rutherford]. I built his qualifying engine for the ’73 500 — it made almost 1300 horsepower (circa 960kW) when he set that thing on pole. It sounded like a turbine coming down the front straightaway and Rutherford was as brave as Dick Tracy — very few people could hustle those things like dear old JR. Think about it: a flat-bottom car with big wings, no ground effect, and pretty average tyres.”

Technical director

The respect Roger gained while working for McLaren ultimately paid off with him being named the International Motor Sports Association’s (IMSA) technical director in 1981 — the once-wonderful North American sports car championship.

“Carolyn and I got married in England and then we moved to Bridgeport, Connecticut. I was IMSA technical director for five years. Then, at the end of 1985 came the next change of direction.”

The days of IndyCar drivers coming up through the ranks of bullring-like speedways, racing a Midget one night on dirt and then a sprint car the next on tarmac, were fading and a Formula 2–type category was created and called the American Racing Series. This was eventually changed to Indy Lights. Scott Dixon won the title in 2000 on his way to superstardom.

“I was asked if I could put up a little bit of money and was told that $5000 bought me five percent. So I did it.”

Over the next decade most of the team owners sold their shares and when the Indy Lights programme was sold to CART — the group that ran the IndyCar series — Roger recalls, “I was left with quite a nice chunk of change that I stuck in the bank to retire on.”

Roger bemoans all IndyCars being identical these days, and was especially unimpressed with the direction taken with the engine choice.

“I think we did a disservice by going with the 2.2-litre turbo. In order to get horsepower, there’s no substitute for cubic inches. If you reduce engine size, you’ve got to increase either the rpm or the manifold pressure to get the horsepower you’re looking for. The smaller the engine, the harder it works and the more expensive it becomes to run the thing.”

Undying enthusiasm

After close to 60 years of close contact, Roger’s passion is undiminished. He is flown to Florida each winter to officiate at the 24 Hours of Daytona, watches everything on TV, and is always superbly well informed on the goings on in F1 — plus, of course, there’s his annual trip to the 500 every May. It’s there that his biography is being launched this month.

“Gordon Kirby said he wanted to write a book about my life. I couldn’t understand why. Kirby’s the best motor racing writer in America — surely there were more important people for someone of his standing to be writing about.”

This is all being delivered in Roger’s no-nonsense English accent, which he’s never lost despite having spent half a century in the States. The ‘Boost’ nickname makes sense.

Over the past six and a bit years that he’s been phoning, he’s lost his beloved Carolyn, become a grandfather, and turned 80 — in that order. He keeps talking about making another trip to New Zealand.

“There are some pubs I remember from the Tasman days; I want to see if they’re still there.”

Hardly a phone call goes by that Roger doesn’t say, “You know, Michael, I’ve had a wonderful life — and everything good that’s happened to me can be linked directly back to Christopher.”

I read Roger’s tribute to his great mate at Chris’s memorial service — I only just made it through; I seemed to have something in my eye.