One man’s drive to pay tribute to one of Bruce McLaren’s victorious Can-Am cars saw him emulate the driver and constructor’s ambition, innovation, and attention to detail

By Patrick Harlow, photography by Patrick Harlow and Leon Macdonald

McLaren dominated Can-Am racing for five years but the M20 that debuted at the start of the 1972 season would be McLaren’s swansong in the Can-Am series as it turned its resources and attention to Formula 1. McLaren’s toughest year in Can-Am racing was 1972. Porsche introduced the 917 and it was obvious from its $2M budget that it was there to win. The McLaren team’s budget was barely a quarter of that, making it a case of David versus Goliath.

The main feature of the M20 over the previous years’ M8 was the adjustable front aerofoil and improved cooling and ‘comfort’ for the drivers. This was achieved by removing the huge radiator mounted in the nose and replacing it with two radiators mounted on either side of the cockpit. With the nose now free of the bulky radiator, the design team was able to redesign the nose to improve aerodynamic efficiency and use the front wing to adjust the downforce, improving front-wheel grip. Adjustment of this wing proved to be critical as demonstrated when the M20, driven by Denny Hulme at Road Atlanta, became airborne while following close behind a Porsche 917. Although the M20 was destroyed Denny walked away from it with only minor injuries.

The 1972 season got off to a spectacular start, with Denny driving the M20 to first place on its debut. Porsche came in second and in third place was the M20 driven by Peter Revson. Sadly, without the budget and reliability of the Porsches, Denny only managed to bring the M20 home at the front of the pack twice. His second win at Watkins Glen in June of that year would be the McLaren team’s 39th and final Can-Am victory.

Can-Am Royalty

Only three M20s were built, including the car that was destroyed at Road Atlanta. This car was later rebuilt. All three cars were sold at the end of the 1972 season. One of the cars would score another Can-Am victory in 1974 driven by a privateer but the M20’s day was done. Can-Am racing faded away at the end of that season and was replaced by Formula 5000.

These days the cars are valued in the millions. It was unlikely that I would ever have seen one in the flesh if it hadn’t been for that one day the editor asked me if I wouldn’t mind popping over to Taranaki and having a look at a pretty McLaren M20 that somebody had built in their shed.

That is how I came to be standing by the car owned and built by truck driver Leon Macdonald. Leon started his working career doing a panel-beating apprenticeship but after a few years he decided it was not his thing and for the next four-plus decades worked in the trucking and oil industries, including many years as an owner-driver. Leon’s panel-beating history is evident in the quality of the body but there is a lot more to this car than just a pretty skirt.

So how does one start building a replica of a car that is as close to the original as possible, even down to the gaps between the rivets? To be fair Leon is not new to the world of car building, having built and raced several rally and four-wheel-drive cars in competition-level events.

His friend Dean Savage, although impressed with his rally cars, suggested it was about time he built something decent. Thinking aloud, Leon happened to say he had always liked Can-Am cars; just like that a seed was sown. The nearest he could find to a Can-Am car was a GT40 kit, but he wasn’t keen to outlay the $30K.

Dream Machine

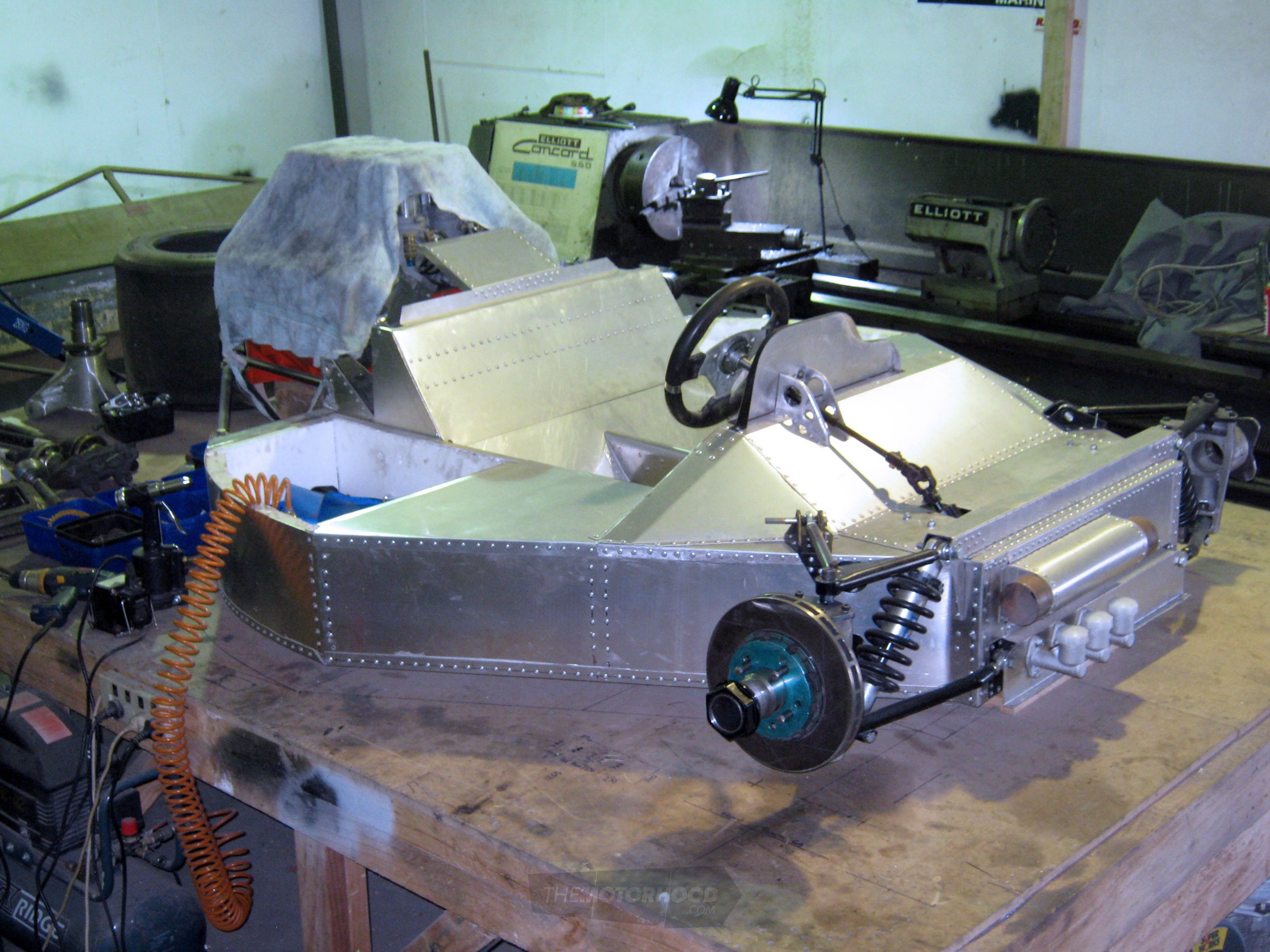

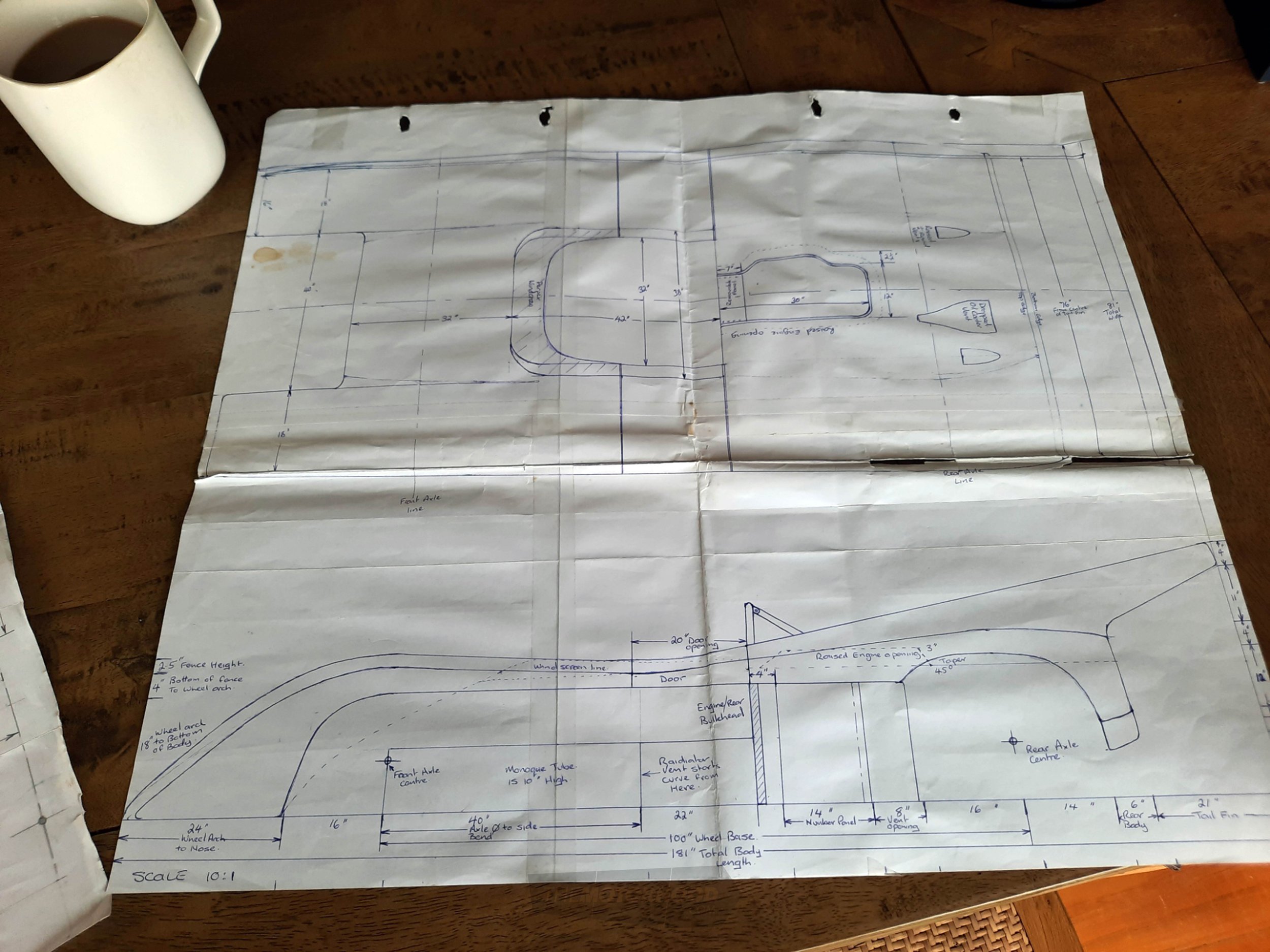

As a boy, Leon had read about the Bruce and Denny Show, an era when Can-Am racing had been dominated by these two drivers. In later years he bought To Finish First by Phil Kerr. This book became his inspiration and a picture of an M20 photocopied onto an A4 piece of paper was his starting point. Using the known wheelbase as a base measurement Leon began by writing scale measurements on the photograph. Then in 2009 he started the build with an investment in some sheets of aluminium that would be used to construct the monocoque chassis. Fortunately he had only to build about two-thirds of a chassis. The final third was the engine and transmission, which was used as a stressed member and carried the rear suspension braced to the gearbox.

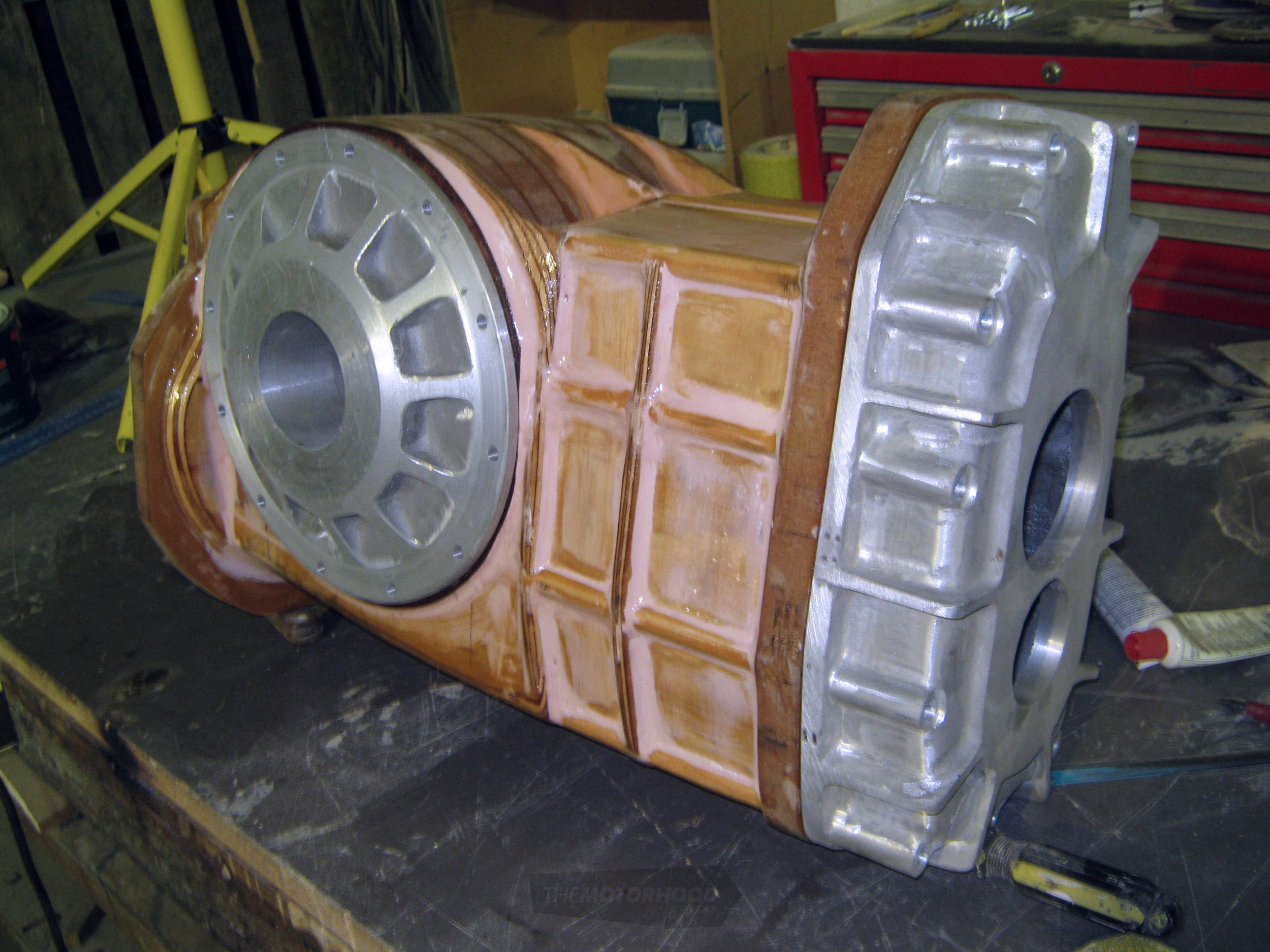

This car was going to be built to a very tight budget, with Leon’s labour being the biggest economy throughout the build. Later that year while doing a five-week stint working in Oman, Leon started work on the suspension uprights. As McLaren M20 uprights are very difficult to buy off the shelf he drew up a scale drawing and made cardboard mock-ups. He initially planned to prefabricate them out of aluminium but in keeping with the original decided to have them cast instead. The cardboard mock-ups were covered in fibreglass to give them stiffness. Next a lot of bog was applied and the mock-ups were shaped into patterns that could be cast by Morrison Enterprises, an aluminium foundry in New Plymouth. Morrison’s was quite enthusiastic about Leon’s project and brought the same expertise to his project that it was using for all the parts it was casting for Shelby American.

Having never made a complete car body or done fibreglassing before Leon once again experimented by making a one-eighth-scale body from cardboard and used this as the plug to create a fibreglass mould. This was followed by a one-eighth-scale cardboard model of the chassis held together with duct tape.

Now all Leon had to do was convert everything to full size. Compared with everything else the folding and the riveting of the aluminium chassis was one of the simpler tasks as it was just straight engineering. Despite that Leon spent a bit of time hunting for rivets that would look as close as possible to those used on the M20. Originals were no longer in production.

At this point I was getting a picture of the true size of this project. It was about to get bigger.

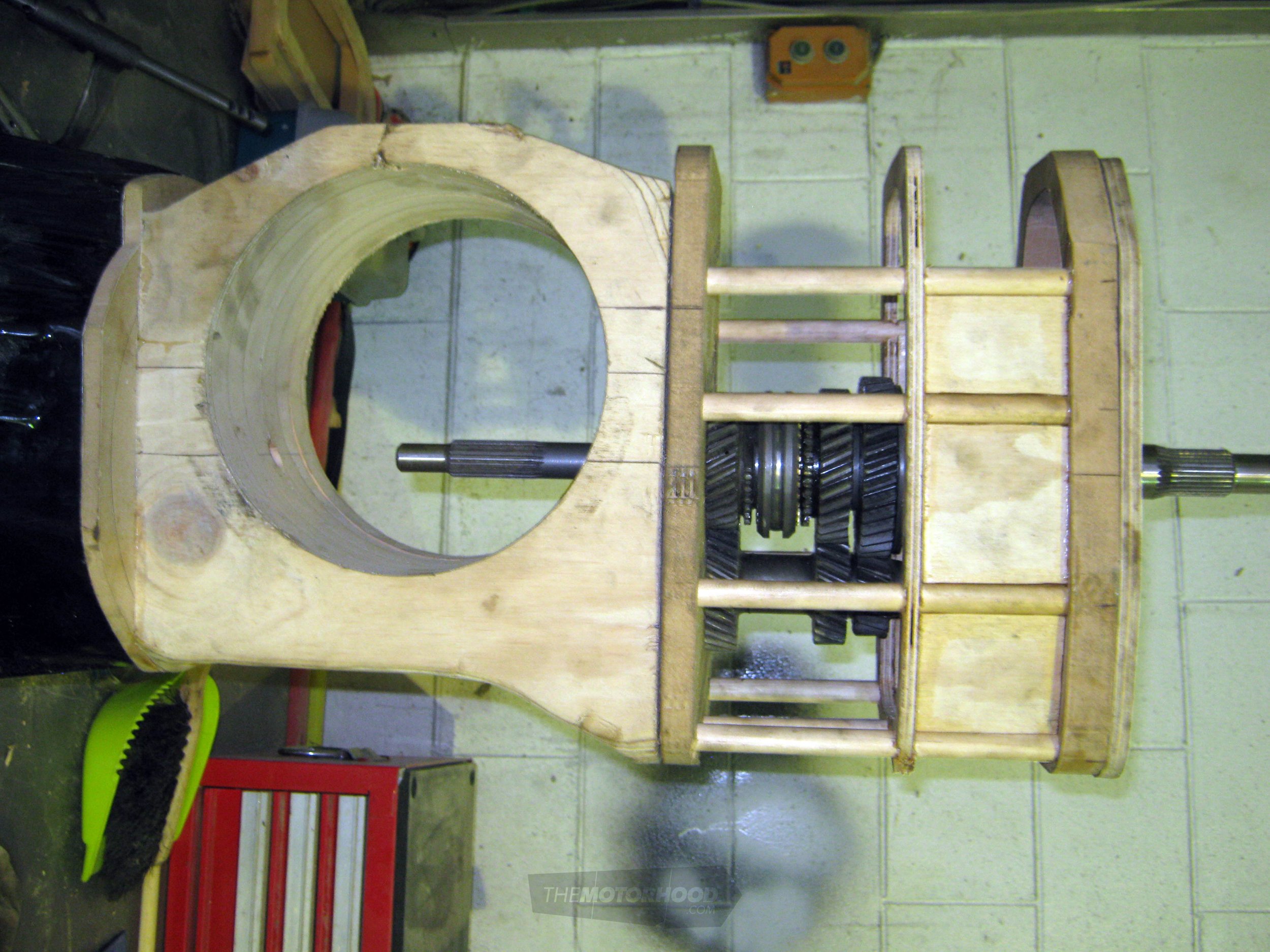

Custom Transaxle

I have mentioned that McLaren M20 parts are thin on the ground. Those that are available such as the LG500 Hewland transaxle (about $54K) were not viable on Leon’s limited budget. Leon decided the only way he would have a transaxle on the car was to build it himself along with a gearbox and a bell housing. Having competed in Nissans for most of his life Leon stripped down a Nissan Patrol gearbox that he had on the shelf and decided to use as many of the internals as possible in his handmade gearbox. As always he started with a drawing to get the sizes sorted. This was followed by the purchase of a quantity of custom wood and plywood to make the patterns that would eventually be used for the castings. What followed was hours of painstakingly careful measurements of existing gearboxes and the precise mocking up of Leon’s bespoke ‘trans’.

Throughout this process there was an element of uncertainty as Leon would not know if it would work until the final castings had been made, then machined to the very fine tolerances that are required for a racing transaxle and gearbox, and fitted to the car. If that was not enough he kept on going back to photographs of the original transaxle to make sure he had all the ribs and gussets as close as possible to the same location as in the M20. After he had machined the basic housings the tricky bits were finished by Peter Coster at Connett Engineering.

With the chassis made and the transaxle well under way Leon started work on the body. He was now five years into the project and would be joined by Kelvin Pearce, who had wandered into Leon’s shed one too many times. Almost immediately, the workload halved — as did the stress. Kelvin became a good sounding board for some of Leon’s more crazy ideas. There were times when Leon was ready to put the project into the too-hard basket and walk away but then Kelvin would turn up and things would not seem to be as difficult as they had been previously. It is very hard to build a car from scratch by yourself; having a friend who is going to turn up every week ensures that the car will be worked on regularly. Some weeks it would be more talk than action and at other times work would continue with hardly a word being said.

With each passing week a little more progress was made. The body was shaped and then tweaked many times. Photographs gave the basic shape and a few measurements but not having an actual car in the shed with them meant that several curves were finalised with the ever-reliable ‘eyeometer’. With his panel-beating background Leon was able to finish his bodywork to a higher standard than the original. When it came time to paint the body he was able to borrow the spray booth of Miles Hicks in Ardmore and applied the sunburst yellow with the contrasting royal blue highlights himself.

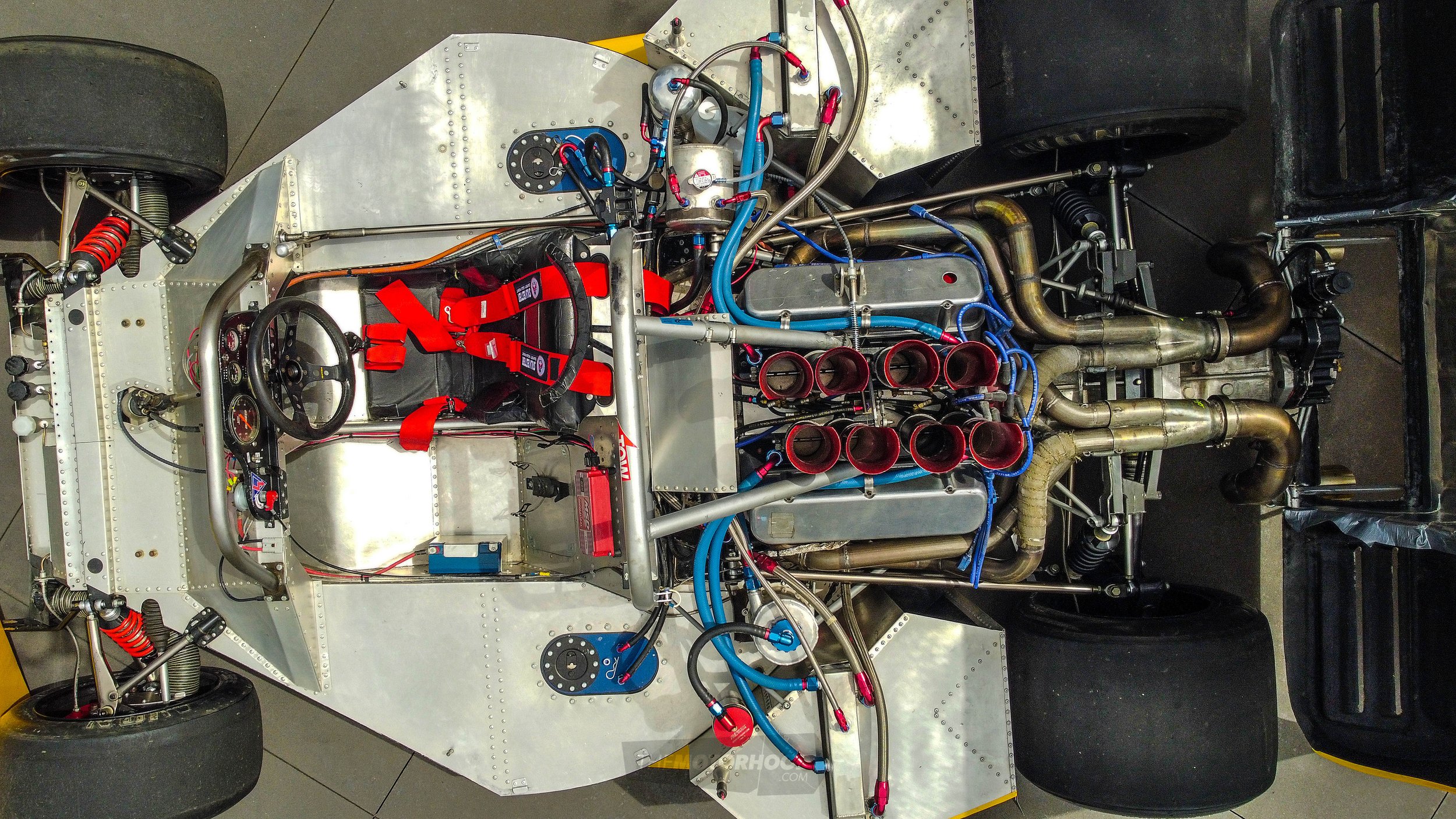

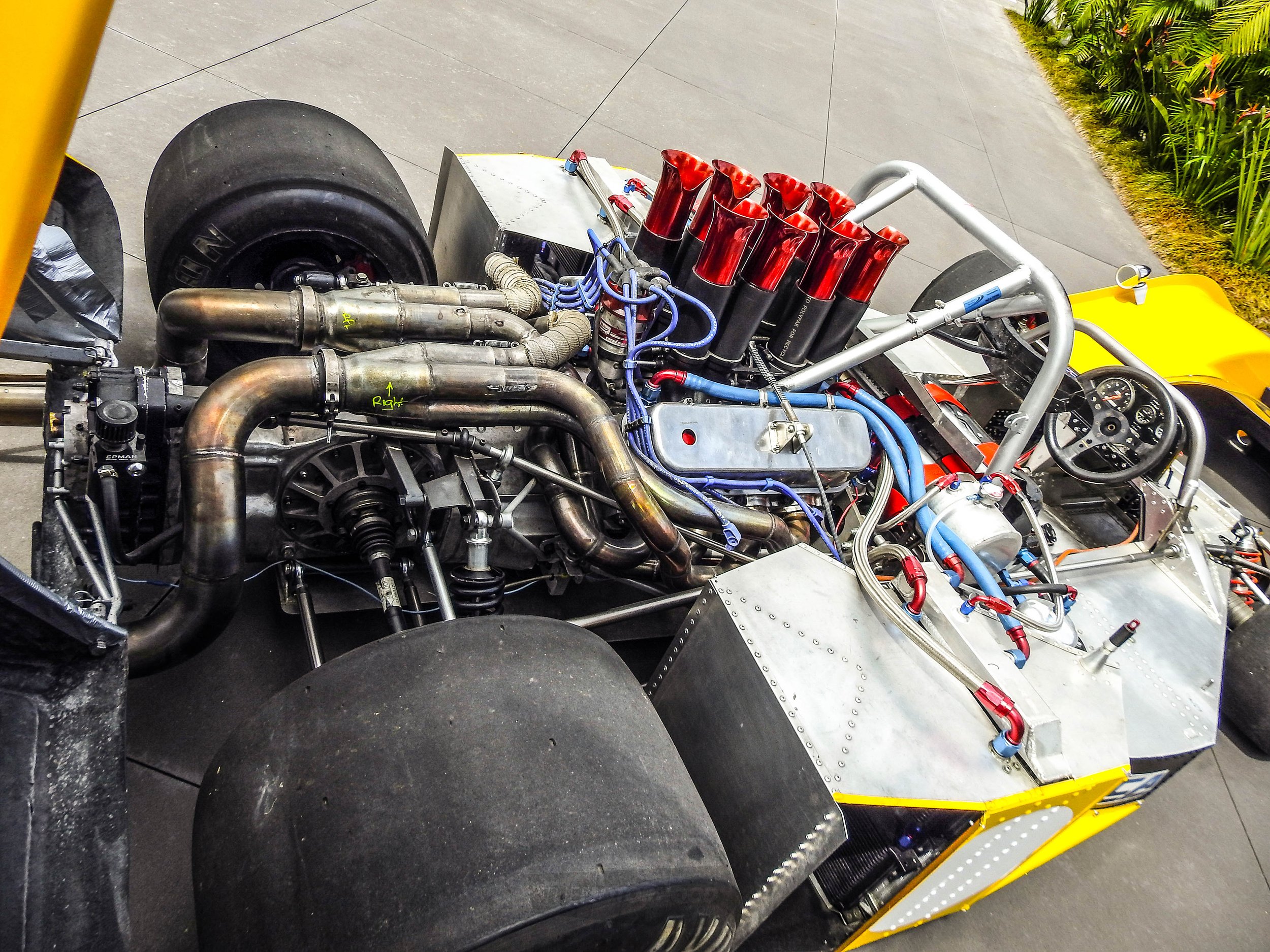

Leon’s car is not an exact nuts-and-bolts replica. It’s more of a tribute car that commemorates one of the greatest racing teams in living memory. Not everything from the McLaren M20 could be copied exactly; concessions had to be made. The McLaren had an all-alloy engine and again because of budget Leon went with a cast-iron 510-cubic-inch (8.4-litre) Chev V8 short block. The original McLaren blocks were all aluminium and built by Reynolds Aluminum not General Motors. Reynolds cast and machined the parts for the engine and then Gary Knudson put them together for McLaren. Hens’ teeth are more common than these engines. However despite it being a cast-iron block, Leon added as many go-fast / period-correct parts as he could afford, including Chev ZL1 alloy heads. To get it to run smoothly on New Zealand fuels a modern MSD ignition system was fitted.

That McLaren Feeling

The 700bhp (520kW) engine was built by Steve Hildred ready to be raced. The engine has no engine mounts as it is an integral piece of the chassis. This is a good segue to introduce the parts on this car that are genuine McLaren, such as a McLaren M8F/M20 dry-sump pan that bolts to the bell housing and the chassis plate. This and the genuine McLaren M20 steering rack were bought from Vintage Engineering in California. Once the company heard about the extent of Leon’s project it agreed to sell him the parts at a reasonable cost.

The finished car was started for the first time in 2019. The biggest unknown was the gearbox and transaxle. As expected, this required a bit of tweaking and fettling to get it as good as possible but it represents a fantastic achievement, especially as it was built without the millions of dollars a car manufacturer would spend on the process.

It was a big day when, on 17 March 2020, Leon’s M20 was rolled off its trailer at the Manfeild racetrack and driven in anger for the first time at a track day hosted by the Manawatu Car Club. It was a very successful day apart from a small engine fire caused by fibreglass bodywork being too close to the exhaust. Naturally Leon takes full responsibility for this as he made the exhaust system. Apart from that little heart-stopping moment his day at Manfeild probably ranks as one of the best days of his life.

As a result of the interest in this project from around the world Leon has found a market to which he can export some of his M20 parts. Besides wheels another transaxle was sold to Australia. So far two bodies have been pulled out of the moulds. A second M20 has been started in Wellington using one of Leon’s bodies as well as his uprights and wheels. He is watching its progress with interest.

Some of the highlights for Leon were putting the body on the chassis for the first time, starting the engine up on the dyno for the first time, and feeling the car move for the first time as he eased the newly installed clutch out. Oh, he also said, “Driving a McLaren M20 on a racetrack for the first time was pretty cool too” — something most of the world will never experience.

This article originally appeared in NZCC issue No. 378