Suzuki’s magnificent failure, the rare rotary-engined RE5, makes an eye- and ear-catching alternative to the now traditional inline fours that revolutionlised motorcycling

By Ian Parkes

Mazda wasn’t the only mighty Japanese conglomerate to launch rotary-engined vehicles into the market in the mid-70s.

Suzuki had high hopes for its RE5 Wankel-engined bike launched in 1975. It had started looking at the Wankel engine in the mid-60s and bought the licence to the concept in 1970.

Apparently all of the big four Japanese makers experimented with the design, Yamaha even showing a rotary-engined bike at a motor show in 1972. But Suzuki was the only one of the big four to go into production. Like many others at the time, Suzuki believed that the light, compact, free-revving Wankel design would consign piston engines — with their complex, multiple, whirring valves and pistons, which (can you believe it?) had to reverse direction all the time — to history.

Suzuki’s RE5 wasn’t the first rotary motorbike; that honour went to the Hercules W-2000 launched in 1974. 1800 bikes were made before the tooling was sold to Norton. Norton eventually got the money together to make a handful in the late 80s. Dutch maker Van Veen debuted its OCR 1000 in 1978 but it was too expensive, was poorly reviewed, and production stopped after three years.

Build back better

Suzuki had faith it could solve the concept’s known weaknesses — rotor tip wear, excessive heat and a massive heat gradient between the hot and cold sides of the castings, and even its poor emissions — with technology. It threw everything it had, not sparing the kitchen sink, at it. It invented new tooling to machine the engine parts. It went deep into metallurgy looking for new plating compounds, resulting in 20 patents in this area alone.

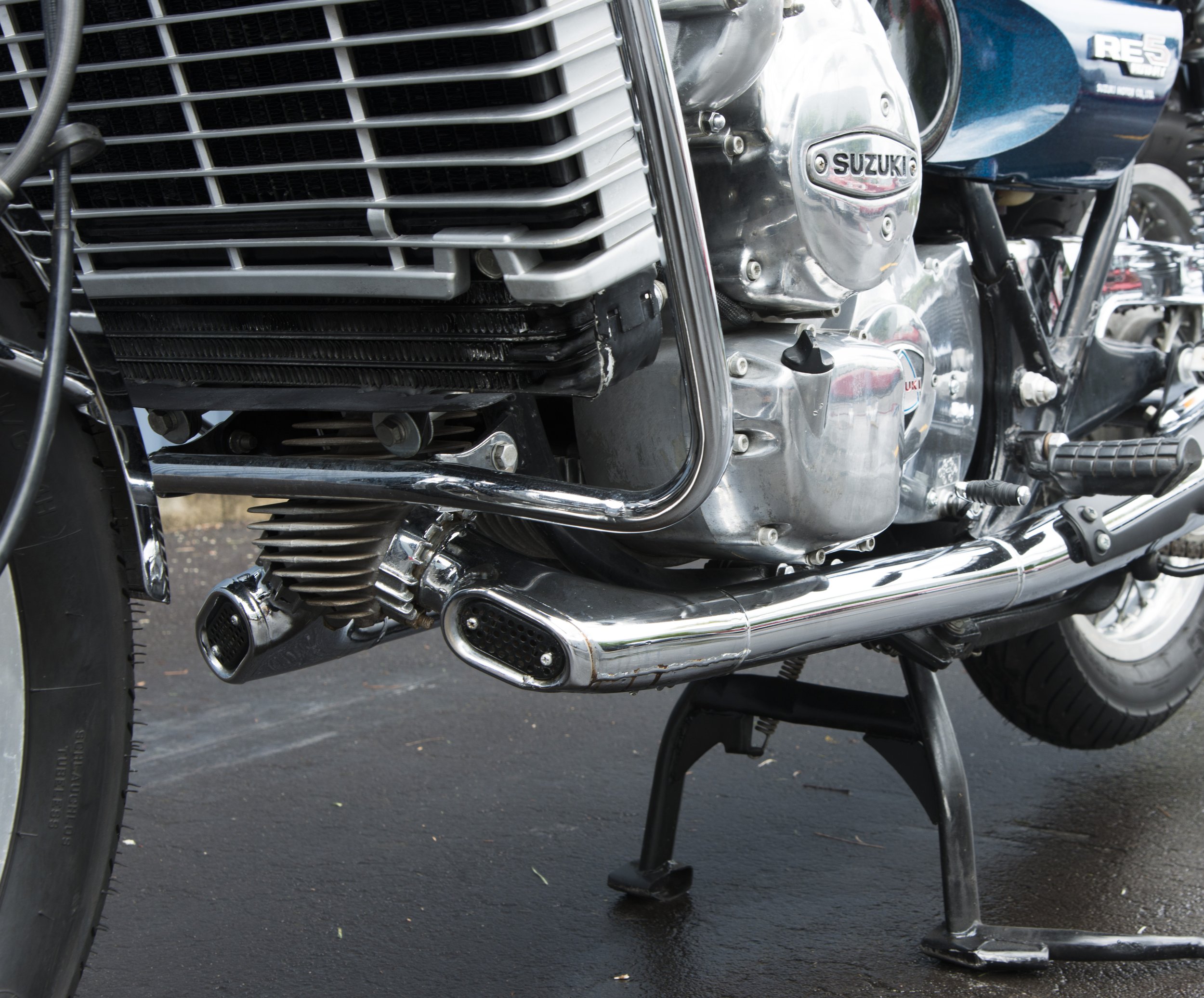

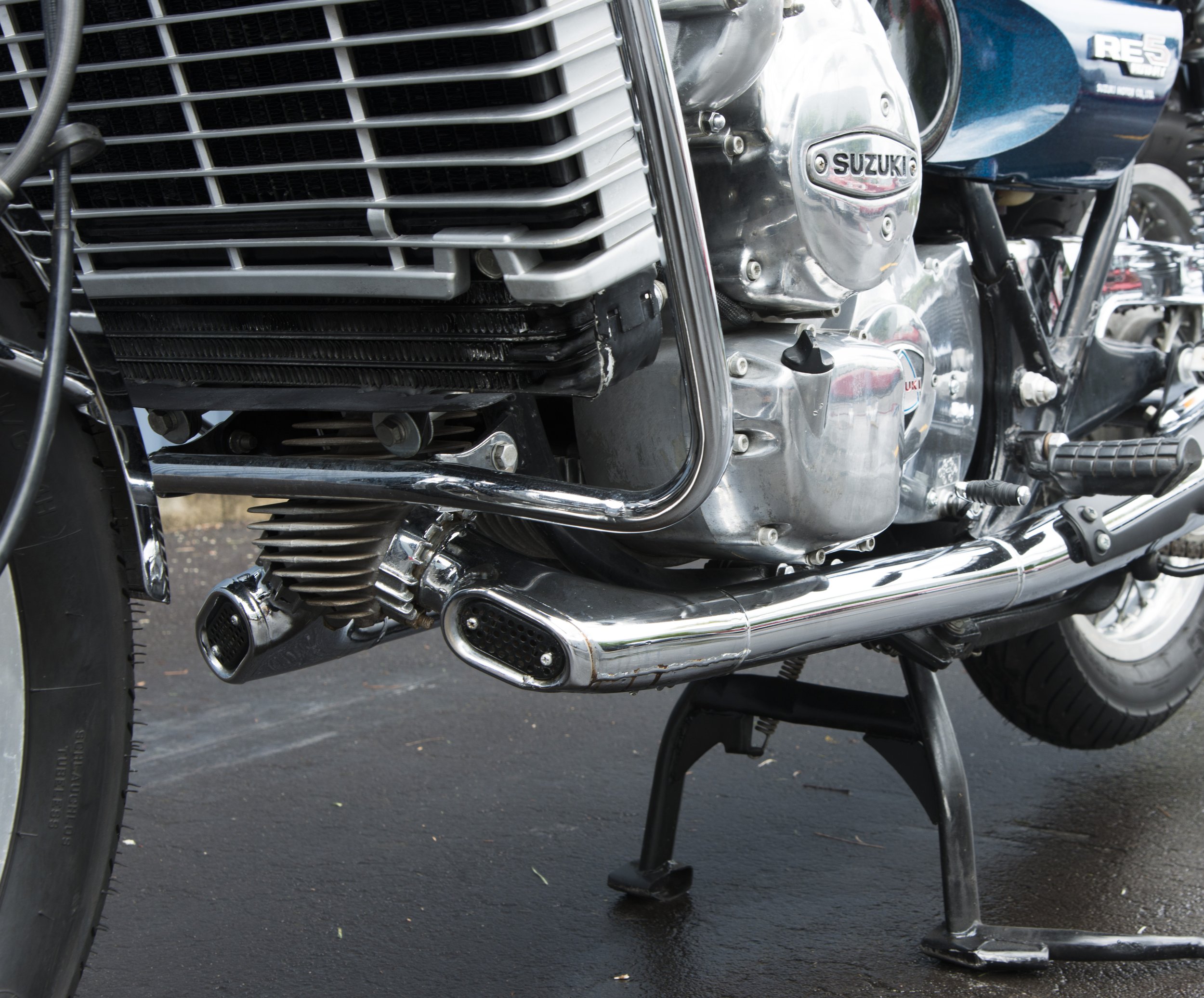

To handle the cooling, the bike has a conventional wet sump, plus an oil cooler and oil pump, and a massive radiator fronting intricate water-cooling plumbing. The bike has a single rotor engine but the exhaust splits in two through a finned flange. Each side features air inlet vents to cool the stainless exhaust pipes inside outer walls. And then they added heat shields to the outside at the usual touchpoints. Fair enough, when exhaust gas temperatures can hit around 930 degrees Celsius.

Even so, owner Chris Stephens says you quickly become aware of the hot bubble of heat surrounding the engine. Nice in winter.

Bruce Meyer, Mr Mayers

Mazda addressed the problem of incomplete combustion in the long and skinny combustion chamber with two spark plugs. Suzuki had a ‘better’ idea.

The carburettor is a beast. No fewer than five cables and 12 jets are operated by the twist-grip throttle. There’s an 18mm barrel feeding two induction tracts for low speed running and another feeding a 32mm port into the chamber, which has a separate butterfly valve at the engine side to stop the inlet pipe filling with exhaust gas when the larger barrel is not in use. Another throttle cable controls the oil feed from a separate tank into the carb to aid apex seal lubrication and, through another pipe, to a built-in drive chain oiler.

Part two of their very complicated solution is that the bike also has two sets of ignition points driving the CDI ignition, responding to signals from a vacuum pump and rpm sensors, both firing the single plug. The second set fired the plug on a shut throttle to avoid lumpiness or backfiring on overrun. Apparently it would also avoid a build up of deposits, and provide engine braking. As Chris says, lack of engine braking wasn’t an issue on millions of two-stroke motorbikes so Suzuki was chasing shadows here too. In fact, sources say this second set of points was disconnected on the later A model.

CDI and points? Perhaps it was too hard or it would take too long to develop a custom CDI to do away with the points back then. Chris reckons it would be quite easy now for someone with the right expertise and inclination to map an ideal CDI system that would take the bike’s performance, economy, and emissions to a whole new level.

To infinity and beyond

The 497cc bike produced around 60bhp, a bit less than its own GT750 ‘water bottle’, a water-cooled three-cylinder two-stroke — Suzuki didn’t make four-strokes at the time. Testers at the time noted all those ancillary systems made the bike heavy but they praised its handling and ground clearance.

The bike also featured what Chris calls ‘Buck Rogers’ styling. As this was their flagship and Suzuki had gone all in on its manufacture, it called in Giorgetto Giugiaro to design the bike. The most notable features are the ‘tin can’ instrument pod, the perfectly circular indicators, and other circles scattered around the bike.

The new tech was a big gamble but, to head off one potential problem, Suzuki said any engine problem would be fixed with an exchange engine. It didn’t want inexperienced mechanics fumbling about with it.

And yet it didn’t sell. Only 6500 of them were sold around the world in its entire production run. In its second year in the huge West German market, Suzuki sold just one RE5.

Something (inexpensive) had to be done. Perhaps it was a bit too Star Wars for the notoriously traditional bike-riding community? The A model was launched, deleting some features like the chain oiler and the secondary ignition system, but most obviously the pod was ditched and the bike reverted to a conventional instrument cluster and tail light from the GT750 parts bin. The bold stripes and metal flake colours were toned down to a much more traditional black with gold pinstriping as shown here, and Suzuki crossed its fingers.

Punters weren’t so easily fooled and continued to stay away in droves. After just three years of production, the new production line was closed down. It nearly sank Suzuki, so a lot was riding on its next bike. Not surprisingly 1977’s GS750 was based heavily on Kawasaki’s massively successful Z900, to the extent it featured the same valve angles, valve size, and valve timing. Until then, if you remember, Suzuki’s expertise was in two-strokes.

Since then, many have piled in on the RE5’s failure over the years. In 1985, Cycle World was particularly unkind, casting it as one of the 10 worst motorcycles. It had: “the mechanical simplicity of a 747, the sound of an out-of-tune B-29, the performance of a fair-to-middling 350 and the aesthetic appeal of a high-speed train wreck, all in a highly unsalable motorcycle”.

Chris, having three of them, is obviously more of a fan and he doesn’t agree with the ‘fair to middling’ assessment. “It’s quite strong and because of the flat torque curve it is surprising how fast you get along,” he says.

“The long wheelbase, higher footpegs, and good ground clearance made it both a good tourer and good in corners and handling.”

Brand new

So the RE5, surely one of the finest expressions of engineering for its own sake, deserves veneration. He has two of the 1975 models, one in each colour, and one of the 1976 A models. This black bike is in immaculate condition. “It’s brand new,” says Chris.

A dealer in the States had kept it in its original crate. Then it went into a private rotary collection in Ohio and Chris bought it from there. It had a rat’s nest in the swing arm, so Chris was pleased to get it out of the crate where it can be protected against further decomposition and predation.

Chris says the weight isn’t apparent until you go to put one on a sidestand, as it sits at quite an angle. The high and pulled-back bars are ‘different’ but very comfortable and the extra windage isn’t a problem at New Zealand speeds. He says the engine is super smooth.

“You hear but you don’t feel it. It’s vibration free from tickover to 7000 revs.” Chris says there’s a bit of harmonic vibration that creeps in around 3700 revs. “You think, oh, what’s that? It feels mechanical but it’s just other stuff joining in.”

We didn’t go for a ride with old fuel in the tanks but Chris started one up. The single-cylinder engine settled into a distinctive beat that sounds more like a multi-cylinder than anything, but with a distinctive “barp barp barp” on the overrun.

Buyers in the ’70s stayed away but I bet there are more than a few of them who would want one now.

This article originally appeared in NZCC issue No. 375