Donn Anderson endeavours to make a case for Triumph’s last sports car, the aerodynamic TR7. The news is not all good, and not all bad

By Donn Anderson

Whistling through the Hertfordshire countryside in England on a fine, clear winter’s afternoon 34 years ago it was hard to believe our sports car was another ‘close but no cigar’ model from a struggling British Leyland conglomerate. Was this much-maligned Triumph TR7 really the disaster painted by the pundits, or a classic in waiting?

Look past the poor build quality and annoying faults which was the default starting position for assessing BL cars of the era, and the distinctive — some would say distinctively ugly — TR7a and you will find a car that has weathered remarkably well over four decades. Indeed, look around some of the odd shapes of many current mass production cars in 2021 and you have to admit this last hurrah of the Triumph sports cars is not so outlandish.

Stuart Bladon, a long-time motoring journalist who spent 25 years at Autocar magazine in Britain, owned one. He rose to deputy editor before he left in 1981. He likes open air driving but was perturbed by high insurance costs for his modest Peugeot 205 CTi convertible. A friend suggested he swap to a classic car with a much cheaper limited use insurance premium and thus he became the owner of a 24,000 mile TR7 convertible, first registered new in August 1982, a year after production ended.

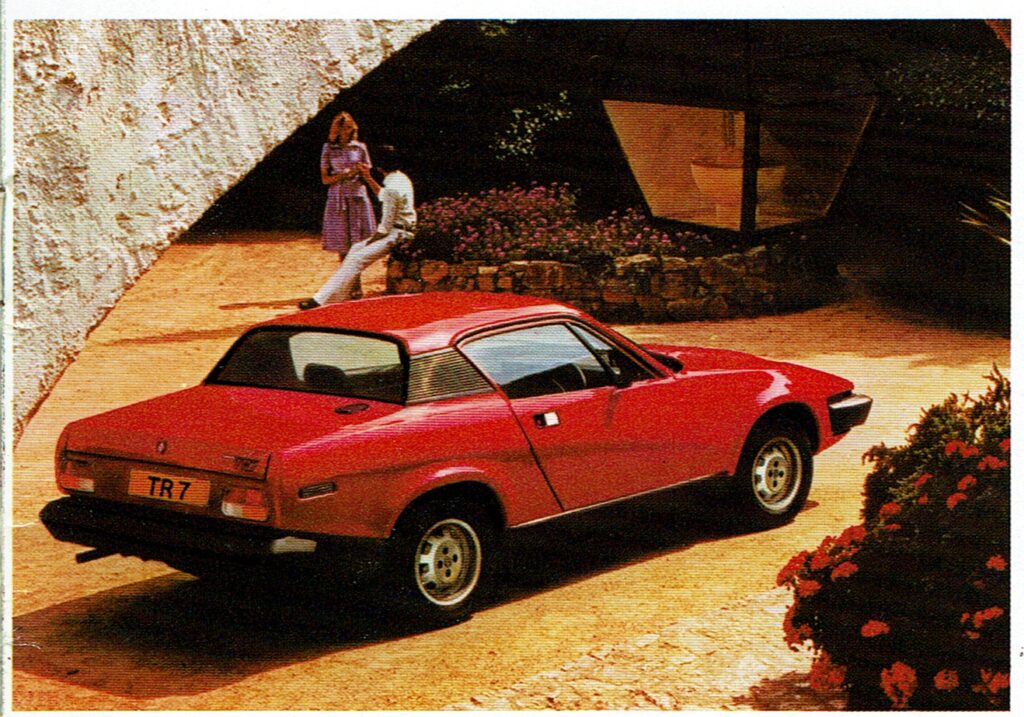

Bladon was the European correspondent for New Zealand Car magazine and Stuart and his charming wife Jenetta kindly invited my family to lunch at their home in Radlett during our time in Britain in 1987. Later that day Stuart simply had to take me out in his prized red TR7, top down, of course. The car’s civilised ride, decent handling, and low noise levels were immediately apparent.

Unlike most people, Stuart liked the wedge shape of the hardtop version and, having owned a Triumph Dolomite 1850 with its similar engine, he felt the basic engineering was good. Later, even after more than 20 years of ownership, he still enthused about the car.

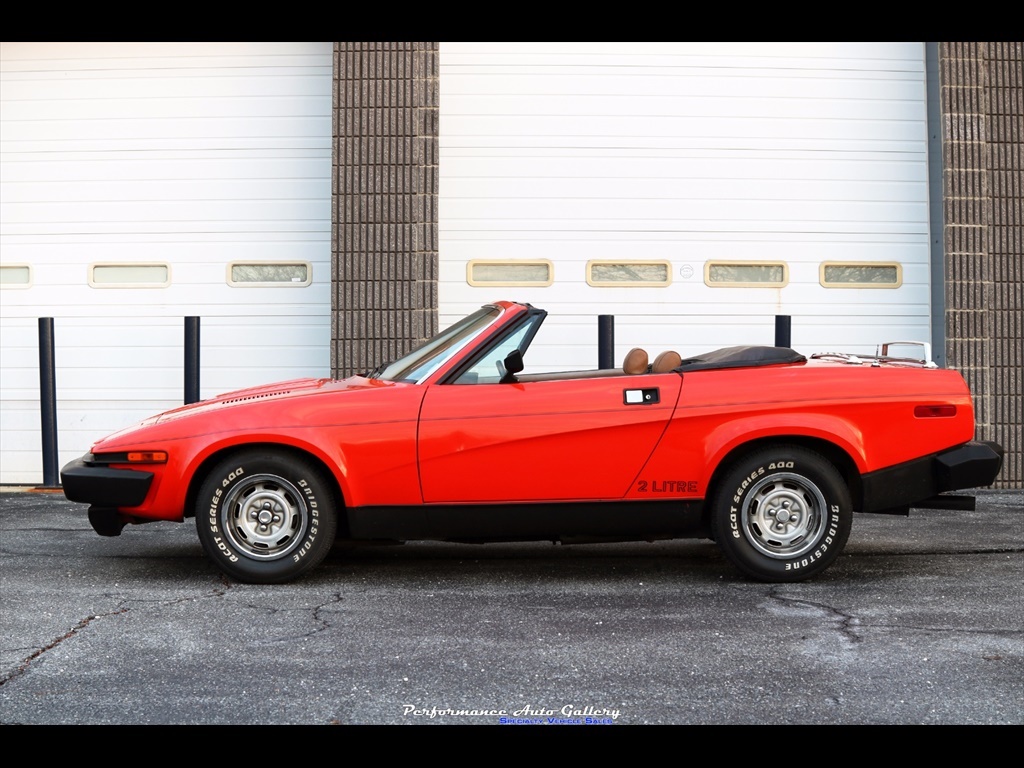

Soft-top saves style

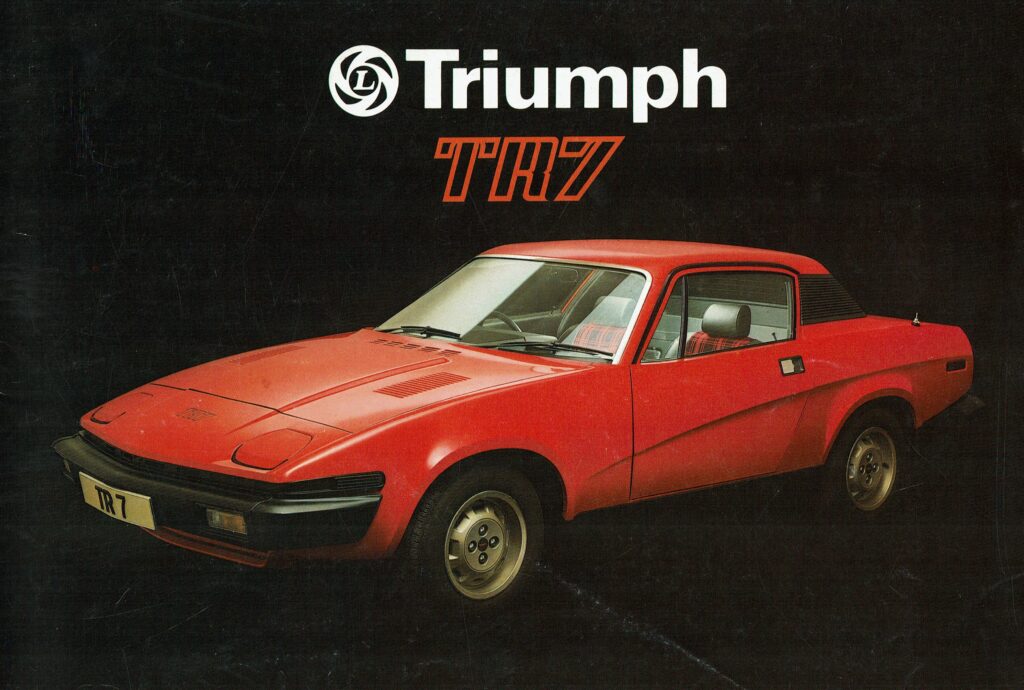

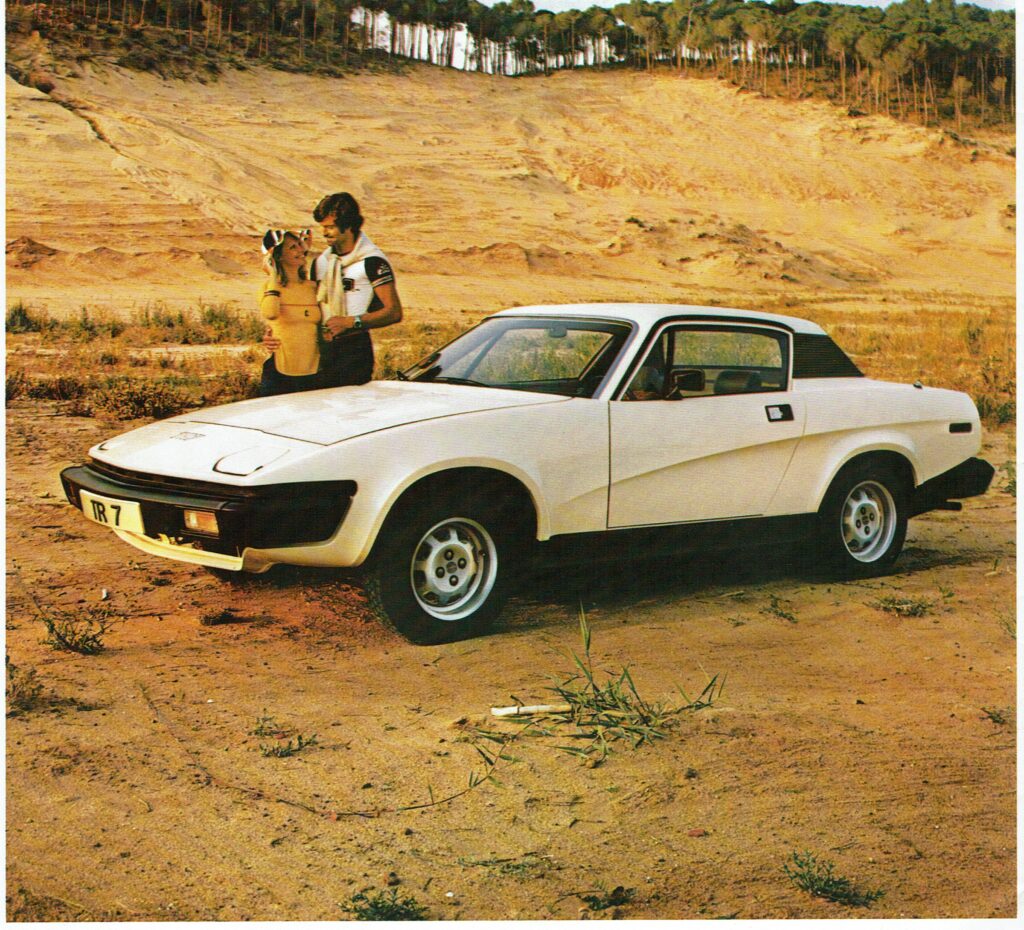

Traditionalists scoffed at the looks of the swoopy albeit aerodynamic TR7 coupe when it launched in September 1974, especially as the replacement for the four-square and meaty 6-cylinder TR6. The arrival of the drophead/convertible version in 1979 placated the moaners somewhat and its looks attracted more approval. It’s generally accepted that the styling works better in open form although Harris Mann, the one-time controversial chief designer at British Leyland who penned this extravert Triumph, might disagree.

At the unveiling of the hardtop rival designer Giorgetto Giugiaro walked around the car and said, “My God. They’ve done the same on this side.” Other kinder souls conceded it was the shape of things to come.

London-born Mann felt the cutting-edge design was simply a bit too advanced for many at the time. Years later he pointed out that many observers were surprised the TR7 still looked so modern. Certainly Harris came with impressive credentials, having worked on the shape of the first generation Ford Escort and Capri before moving to the British Motor Corporation — and a frosty reception. Mini creator Sir Alex Issigonis was aloof with newcomers. He wouldn’t talk to Harris Mann because he didn’t have an engineering degree.

The first BMC assignment for Mann was involvement in the Morris Marina and then the Austin Allegro before being given a freer hand in shaping the Austin Princess — another controversial wedge design that hinted at the later TR7 with its heavily raked windscreen and high tail. That wedge wasn’t the sole complaint of the critics though. They also slammed the sculptured inserts along the body flanks and near-vertical rear window of the TR7 hardtop.

During development Mann ran into some of the engineering problems associated with a chaotic and failing British Leyland. The Princess was intended to be a hatchback — the shape makes much more sense with that arrangement — but the chiefs decided otherwise. The final BLMC project for Mann was the Metro. After going freelance he was a design consultant for BMW in the mid-’80s and worked with MG Rover on the MGZ.

On the mechanical front, oil pressure and low coolant level warning lights became a familiarity for many TR7 owners, as did poor assembly quality, but Mann should not be blamed for any of these induced maladies. Nor was he responsible for the plastic and flimsy facia, garish interior colours and checkered seats made from Rupert Bear’s trousers, or the sluggishness of the pop-up headlamps that increase with lack of attention.

Submarine safety

Slightly longer than the TR6 and with a shorter wheelbase, the TR7 was always aimed at the North American market where open cars were expected to be banned. An enclosed two-door was the plan until the drophead/soft-top emerged five years later. Original plans for the TR7 to have a Targa roof were also shelved because of engineering obstacles, although the car would be offered with an optional sunroof.

Other advanced features did make it past the BL cost-cutters. The slant four, single overhead cam motor enabled a low bonnet line. In a head-on impact, it was designed to submarine underneath occupants, making it one of the safest sports cars of the era. Apparently it was also the first production car to have side-impact beams.

The bonnet is hinged at the front and opens from the rear, and an interlock device prevents it slicing through the windscreen in a frontal crash. Prominent steel-reinforced polyurethane bumpers were clearly designed to comply with US safety rules. Contrasting with the separate, heavy gauge, box-section perimeter chassis of the TR6, the TR7 structure is based on a platform chassis integral with the bodywork, using strong sill and floor members.

One problem with the sharply sloping bonnet, in common with many later cars, is that it is difficult to see the front of the car from the driver’s seat. The three-quarters rear vision, constrained by the heavy ‘B’ pillars, is poor. On the positive side, the spacious interior is well equipped, the seats are good, and there are well-placed controls, clear instruments, and a reasonably large boot.

A total of 112,368 TR7 hardtops/coupes were built and roadster production amounted to 28,864, plus around 2500 TR8 models. The first right-hand drive examples for the UK and other markets commenced in May 1976 and the initial examples arrived in New Zealand later that year, retailing for $14,750. Few were sold in our market and by the time the last of the new examples arrived here in 1981 the local asking price had risen to $19,500. Production ended in October 1981. In June 1984 the Triumph marque, which had given us many fondly-remembered cars and plenty of sports cars, was finally farewelled.

Live axle lives on

TR7s and the V8 variant, the TR8s, are thin on the ground here but international prices, which have long been low, have shown an upward trend in the past three years. Tidy or restored British TR7s range from the equivalent of $9000 to $25,000, while a rare TR8 convertible recently appeared with an asking price of $40,000. Since so few new examples were sold in New Zealand, little wonder it is now difficult to find one for sale on our shores.

Measuring just over four metres, the TR7 sits on a short wheelbase and has a conventional suspension with MacPherson struts and coil springs up front, and a coil sprung four-link live rear axle with a rear anti-roll bar. Spencer (Spen) King, the engineering man behind the Range Rover, reasoned the live axle did not sacrifice anything in handling. He claimed Triumph developed the TR7 to a standard equal to that of any competitive car with independent rear suspension, mainly by ensuring there was enough wheel travel and by careful work on damping. Rack and pinion steering is unassisted and front disc/rear drum brakes have never been known for their enduring strength. Alloy wheels became optional towards the end of production but most TR7s came with 13-inch diameter steel rims.

Initially the car was built at the strike-paralysed Speke plant in Liverpool before production moved to the Coventry factory of Canley in October 1978, signalled by distinctive Triumph motifs on the bonnet and tail. Assembly quality was much better on later models, especially when production was transferred to the Rover plant at Solihull in 1980. All TR7s use the 1998cm3 4-cylinder Dolomite Sprint cylinder block with the alloy 8-valve cylinder head, and twin SU carburettors. The 16-valve, 95kW (127bhp) Sprint engine would have endowed the car with much better performance since the standard motor in the TR7 produces a modest 78kW (105bhp), and those bound for the USA developed even less. Another missed opportunity.

The English Corvette

Top speed is around 180 km/h and the car runs from a standstill to 100 km/h in just under 10 seconds. Performance is reasonable rather than startling, although the engine pulls well from 2000rpm through to around 5000 revs and flexibility is good. Triumph strengthened the roadster and overall weight is more than the hardtop.

When the call came to fit the 3.5-litre Rover V8 engine into the TR8, output rose to 99kW (133bhp) for the earlier production with twin Zenith-Stromberg carburettors and 102kW (137bhp) with

Bosch fuel injection on the last examples. Most TR8 production went to the USA where some owners described the car as the “English Corvette”. In Australia several cars have been restored with the 4.4 litre P76 V8 powertrain, giving a further lift in performance.

Early TR7s came with a 4-speed Dolomite gearbox that buyers should avoid due to a notchy action and a habit of losing its synchromesh on second gear. From 1976 the much more sturdy 5-speed Rover SD1 transmission became optional, a smoother gearbox that also copes with the higher output of the V8 engines. The third transmission alternative is the less favoured 3-speed Borg Warner Type 65 automatic.

Porsche beater

The car matured in V8 guise and was formidable in international rallying. Britain’s Tony Pond became famous for developing the awesome Metro 6R4 and also for his achievements in taking a TR8 to four outright rally victories in 1978 and 1980. He reckons the TR8 was his favourite rally car even though he once had an enormous accident in one while testing.

“The TR is very sophisticated for what it was and you could certainly live with it as a road car without any problems at all,” said Pond, who felt at the time it would benefit from power steering and that was later fitted to the TR8. He applauded the fact it was fun to drive with limited grip, even though it was able to “beat the Porsches near enough anywhere, especially on the loose” in forest special stages. In rally trim the TR8 looked impressive as well as being competitive. It was another disappointment when Leyland canned its competition department and any further motorsport for the car.

Clearly the TR7 history is far from happy, especially given its extremely poor early reliability. Like several other Leyland products, the car lacked development and could have been so much better. Given conventional mechanicals in an unconventional shape, this final Triumph sports car was never as illustrious as its predecessors. A legend or a lemon? Without driving one most punters will likely pick the latter.

Yet while the rakish TR7 might be regarded as the black sheep of the Triumph TR clan it nevertheless became the best-selling TR of all time. And as it matured into the TR8, the car had the destiny of a rising classic, underpriced in relation to its uniqueness, performance, and rarity.