While flower power took over the rest of the world and music changed forever in the ’60s, the hot ticket for many Kiwi kids was: slot car racing! In the first part of a two-part report Gerard Richards recalls his first true love

By Gerard Richards

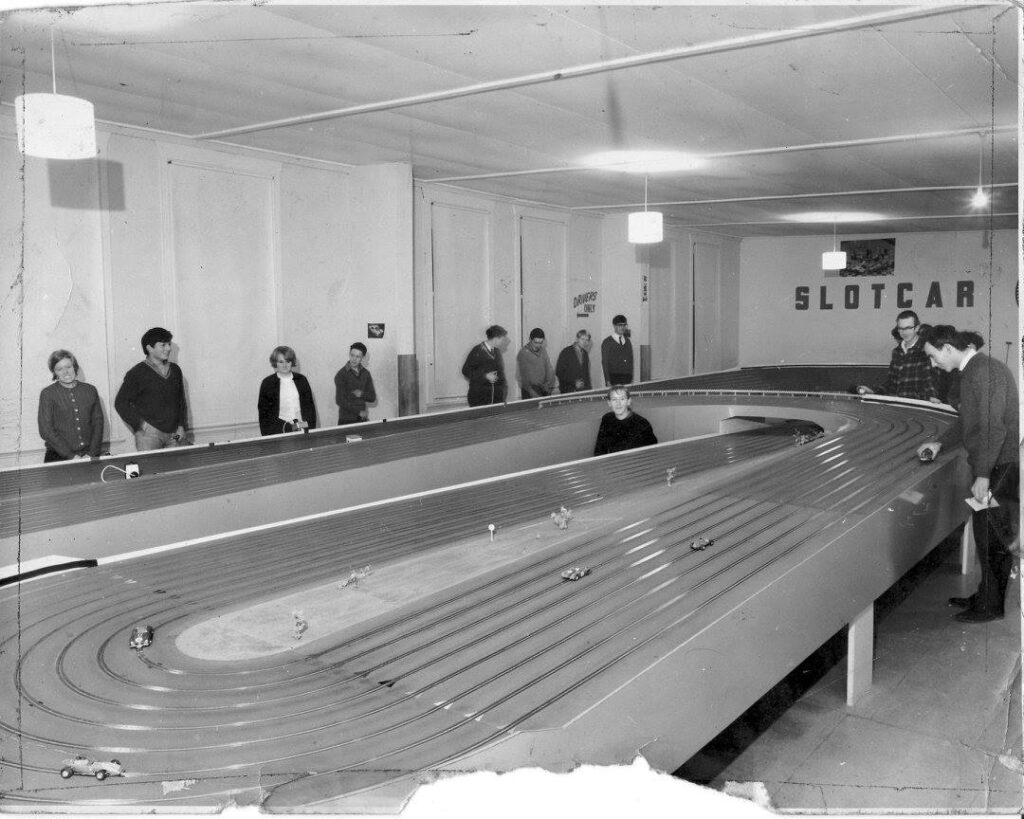

To this impressionable youth, the entrance to Aladdin’s çave was the ‘Pit Stop’, two floors above the Regent Theatre on Auckland’s Queen St. It was an oasis of multi-lane wooden slot car raceways, the walls emblazoned with motor racing art and adverts, with hypnotically attractive model race cars in brightly lit glass cases blasting out in the subdued ambient lighting.

The Pit Stop was a mecca for boys and young men in the mid to late 1960s. A twilight wonderland, it attracted us like moths to a naked bulb, glittering with state-of-the-art dayglo/metalflake sleek racers and hot on-track action.

In 1969, we were young pretenders, only just in the first year of high school. We’d heard word through the grapevine of this groovy place where you could race your own cars on big tracks. At home in ‘the bays’ on Auckland’s North Shore, our previous slot car experience was limited to our home Scalextric (from about 1963) and later Hurricane slot car sets. Our cars ran pretty well there, but we were in for a rude awakening when we ran them on the mighty wooden/copper tape tracks for the first time. They weren’t quite so flash there. Speed and traction were sadly lacking compared with the regulars’ cars. The top cars even on this commercial raceway’s public days were a quantum leap faster than ours.

Kiwis make it their own

Frank Hellawell was the young, slick-haired, Monaro-driving manager of Pit Stop. He was also a hot slot car racer who, along with the elite of the Auckland Club racing fraternity, was embracing a new mode of slot car construction. The steel chassis and solid plastic bodies of the kitset cars of the era, mainly from the US and Japan, were becoming too heavy and cumbersome. By the late ’60s, the locals had decided they could do better.

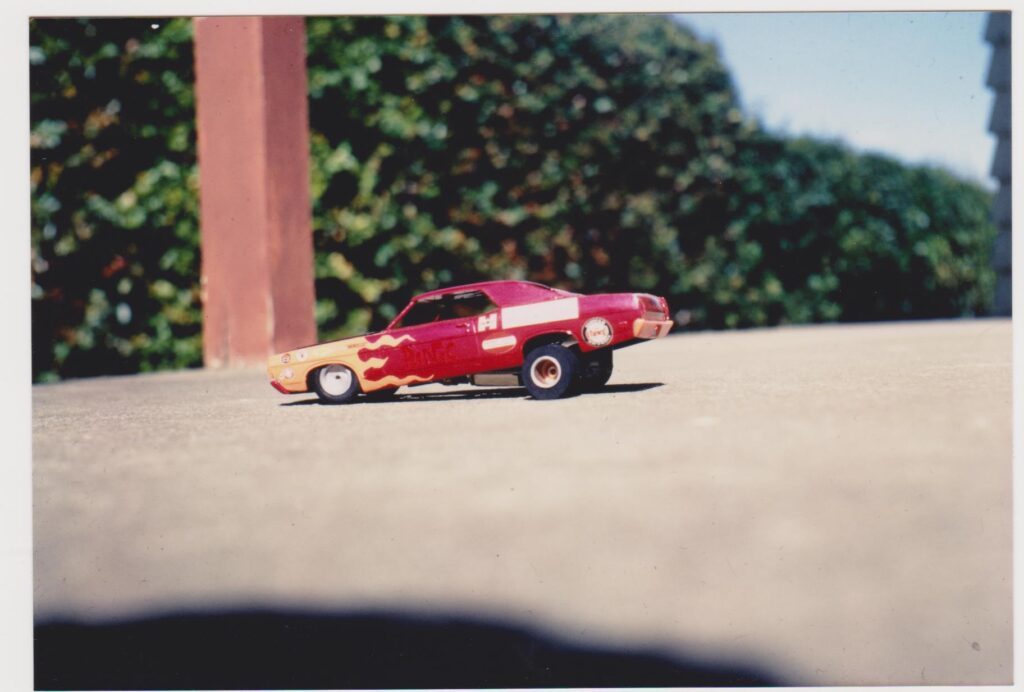

The arrival of a locally custom made U-bracket, which clipped onto the rear bell housing of the new case Mabuchi and other motors, completely changed the playing field. Soldering brass rods and plates onto the U-brackets to support lightweight, vacuum-formed, clear plastic bodies ushered in the ‘scratch built’ era.

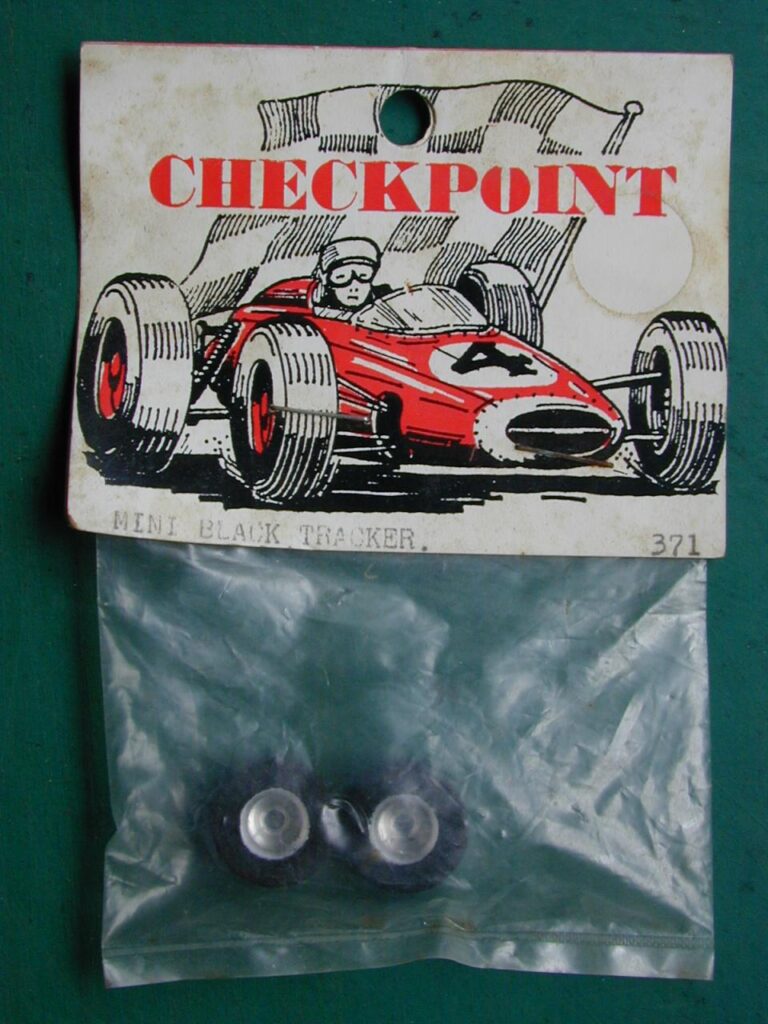

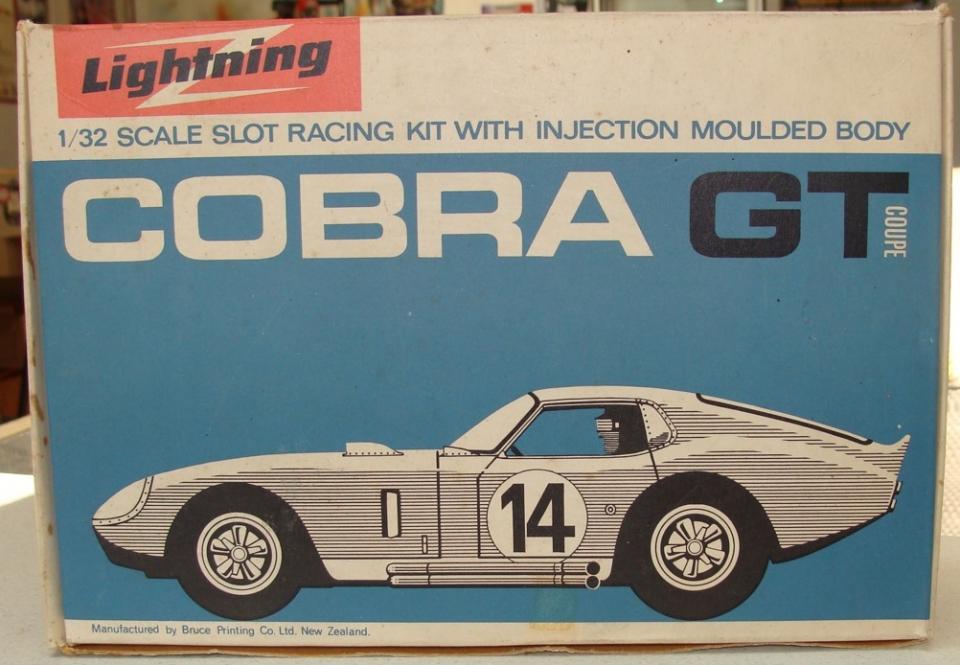

That spawned a vibrant New Zealand slot car parts industry. The leading players were Checkpoint and Royan in Auckland, Royal and Gold Cup in Christchurch, and Lightning in Ashburton. They all made aftermarket parts, chassis, and clear plastic bodies; some made full kits. Until it moved to Newmarket, Checkpoint’s main office was along the corridor the Pit Stop, a handy spot for promoting and selling its gear.

Jandals to the rescue

Rewinding motors for more power was a skilled practice that a number of racers developed. Favourite early motors for this treatment were the Mabuchi 13UO and 16D. This was all part of the desire to gain an edge on the competition.

Frank remembers that, in an import-starved climate, the traction problem was solved with typical Kiwi ingenuity.

“The hard rubber tyres which had been the mainstay were replaced with sponge tyres when someone had the brainwave to create tyres out of jandals.”

A number of complete New Zealand slot car kits were produced between the mid ’60s and the ’80s by the RSL, Classic, and Lightning companies. These small companies adapted American kits for the local market. RSL sourced Marusan bodies and Atlas-based chassis for its Porsche 904GT and Ford GT offerings. Lightning’s Corvette Stingray, Ford Daytona Cobra, and Ford GT/McKee Special cars all used Revell manufactured bodies and ladder-style chassis. Both companies used the underwhelming Hit 1000 case motors supposedly made by Hitachi — although there is some doubt about that.

Drug of choice

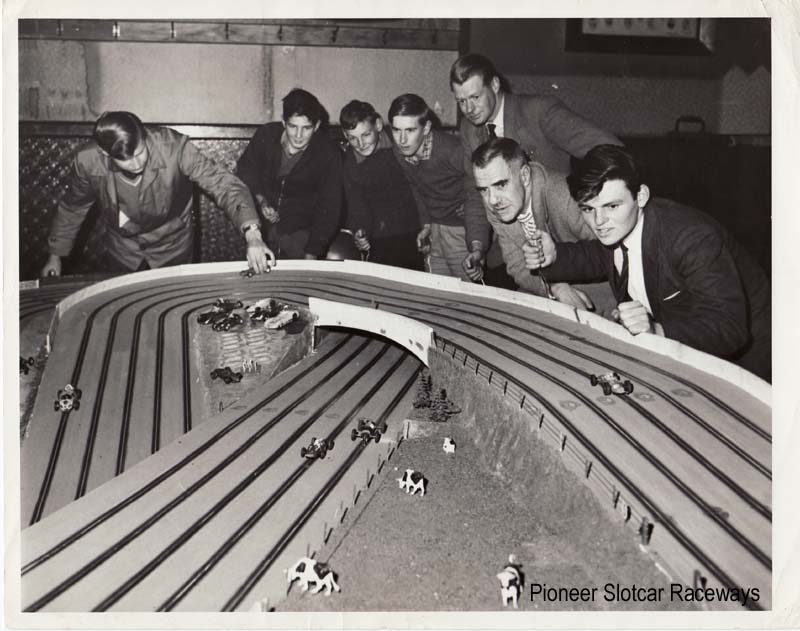

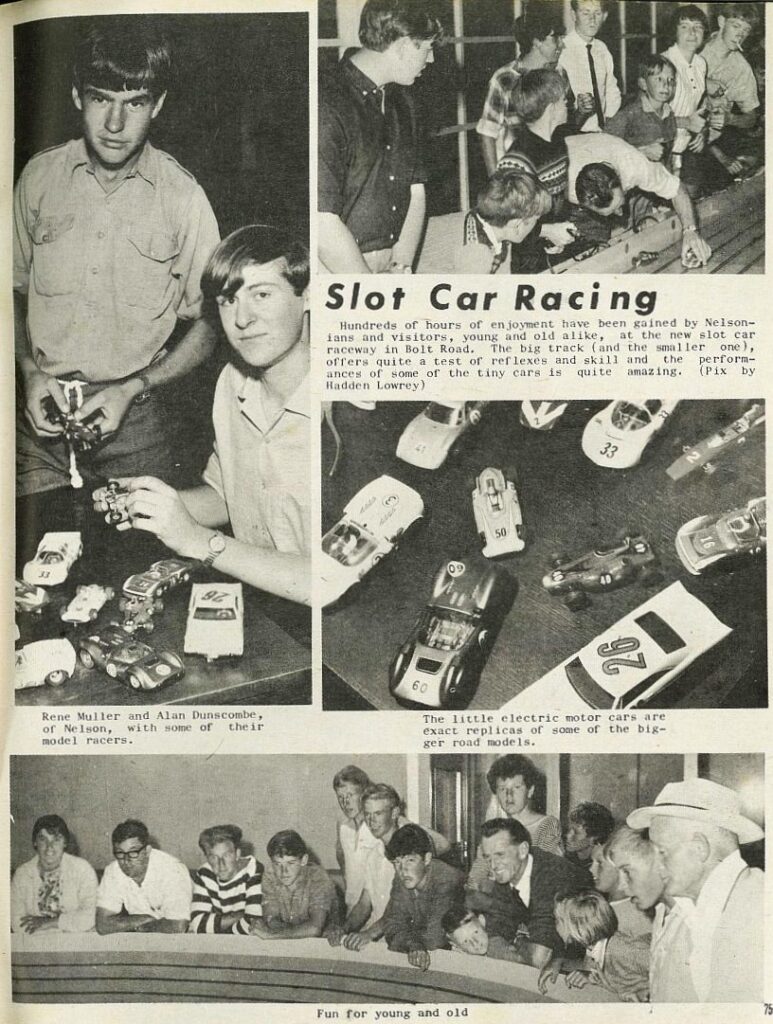

What has been a revelation to me in recent times was the extent to which the slot car craze of the ’60s spread around New Zealand. Club tracks and commercial raceways mushroomed in every centre of any size throughout the length and breadth of the country.

By the mid ’60s slot car action was happening everywhere, and for the mainly young men it was the drug of choice [that’s debatable — Ed.] during the golden era of the scene. They and a few women packed out the racing dens, armed with their latest state-of-the-art hardware, ready for the pumping race action at night-time raceway retreats around the country.

The supreme attraction of this happening scene was of course racing your car against the opposition. Unlike real motor racing, it didn’t cost an arm and a leg — figuratively or literally — to get your thrills.

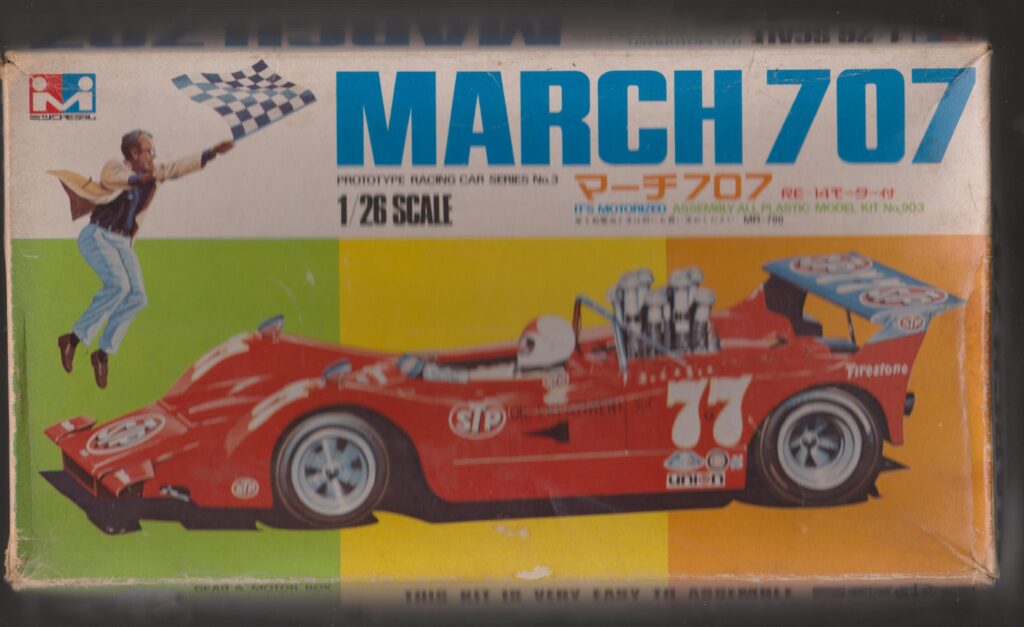

To further whet the appetite for local punters, from the mid ’60s hobby shops carried a range of American and Japanese slot car kit sets, usually featuring wildly alluring racing cover art. The legendary brands included US heavyweights Cox, Revell, Monogram, Atlas, KB, Russkit, and others. The Japanese brands included Tamiya, KSN Midori, Tokyo Plamo, and Mitsuwa. Unfortunately, the dreaded import licensing of the era made it hard to get some American kits. The Japanese offerings were more easily obtained due to the poor exchange rate of the Japanese currency. Sadly, the Japanese slot car industry was fairly short-lived, operating from about 1964 to 1968. A pity, as some of the products were good quality.

Christchurch mainlines US gear

The Christchurch scene stole a march on the rest of the country thanks to an early entrepreneur and a direct US connection.

Operation Deep Freeze, the American Antarctic base in Christchurch, brought a constant stream of US service personnel through the city. This cosmopolitan injection was beneficial in many ways, introducing the Garden City to many of the delights of the wider world. If you were into slot cars, the music business, or cool American cars, Christchurch was the place to be.

The young Americans brought in lots of hot stuff, which the locals were keen to acquire at what seemed like bargain prices. In a product-starved and duty and sales tax protected local market, buying directly from source was an absolute bounty for Cantabrians. The service personnel were not subject to customs charges, of course.

The Americans were keen to race their slot cars — and track equipment — on local tracks while in town. Then they’d sell them off before departing to the ice, knowing they could bring more down on their next visit. So locals scored the up-to-the-minute hardware ahead of the rest of the country. This direct injection also worked for local bands such as Max Merritt and the Meteors and Ray Columbus and the Invaders, who acquired Fender guitars and sound gear at a fraction of what it cost elsewhere — not to mention the many cool LP records not available in New Zealand, which were also quickly snapped up!

MoNZa

Christchurch and much of the South Island also benefited from an entrepreneur who, in very timely fashion, built a whole sequence of commercial raceways throughout the South. Bill Forsyth, a canny wool buyer from Oamaru, formed a company called Slot Car Raceways, which operated tracks at all the sizeable centres in the South Island and had major facilities in Christchurch and Dunedin. Tracks were also built in Nelson, Timaru, Oamaru, and Invercargill, all with big eight-lane circuits called ‘MoNZa’. The scene also featured many club tracks in small places such as Twizel and Otematata. Both Christchurch and Dunedin had eight-lane MoNZa tracks plus a smaller eight-lane track called Riverside. The slot scene was particularly hot in both those cities, the epicentre being the Manchester St raceway in Christchurch.

Frontline racer of the era John Taylor confirms that the Garden City slot car scene was at the cutting edge, thanks largely to the latest equipment courtesy of the Yanks.

He says, “In 1969 everyone had the Mura [or] Champion motors and scratch-built cars with Lexan bodies. Adding to the competitive nature of racing in Christchurch, another commercial complex called Christchurch Miniature Raceways set up in opposition offering a 230-foot eight-laner.”

This was the grassroots of slot car racing during the golden ’60s and early ’70s. Its hardcore members would continue long after the commercial bubble burst in the early ’70s, when for-profit raceways disappeared almost overnight. Characters such as Graeme Saxton (Dunedin), John Crothers (Auckland), Allan Tucker (Wellington), Gill Andrews (Palmerston North), Tony Cook (Nelson), John Taylor (Christchurch), Ivan Bailey (Auckland), and many others are all stalwarts from the classic slot car era who never stopped racing, except for family-related breaks, and are still doing the business at their respective clubs today.

Search for Part Two of this article on this website from July 31, 2023