A flash of silver catches my eye in the microscopic side mirror, accompanied by the distinctive ping of metal hitting bitumen…

By Stewart Allan

It’s day two of a 600km road trip across the South Island’s Lewis Pass, in my newly acquired red Series 1 Sunbeam Alpine. Co-pilot, brother James, awakes from mountain gawking and tells me with some urgency to “pull over”.

I instantly recall the words of the former owner, in his unmistakable Italian accent, prior to our departure.

“This is the moment where I worry you will end – after all, it is a very long drive for a car of this age.”

He is not wrong.

The engine purrs reassuringly, as both of us begin to wonder just what part of the car we are missing. A ute appears in the rear-view mirror; someone leaps out and picks something up from the side of the road. My stomach drops.

“The trip is cancelled, in the middle of the Southern Alps,” I think out loud.

Then the ute pulls up beside us, out bounces the occupant with a beaming face, and proudly hands over a battered but still usable petrol cap.

“Here you go, mate.”

I first spied her online while looking for a replacement for a 1968 MGB roadster that I’d had to sell to pay for the floor of our house. I wept on that last MGB drive, but at least the family wouldn’t die falling through the ceiling. I was instantly attracted to the Alpine’s sleek lines, with a dart-like shape that looked like it was moving even when stationary. I fell in love with the long curved nose that swept through to a pair of unadorned ’50s fins — a bit of Britain and a bit of America in one gorgeous little package.

Rare beauty

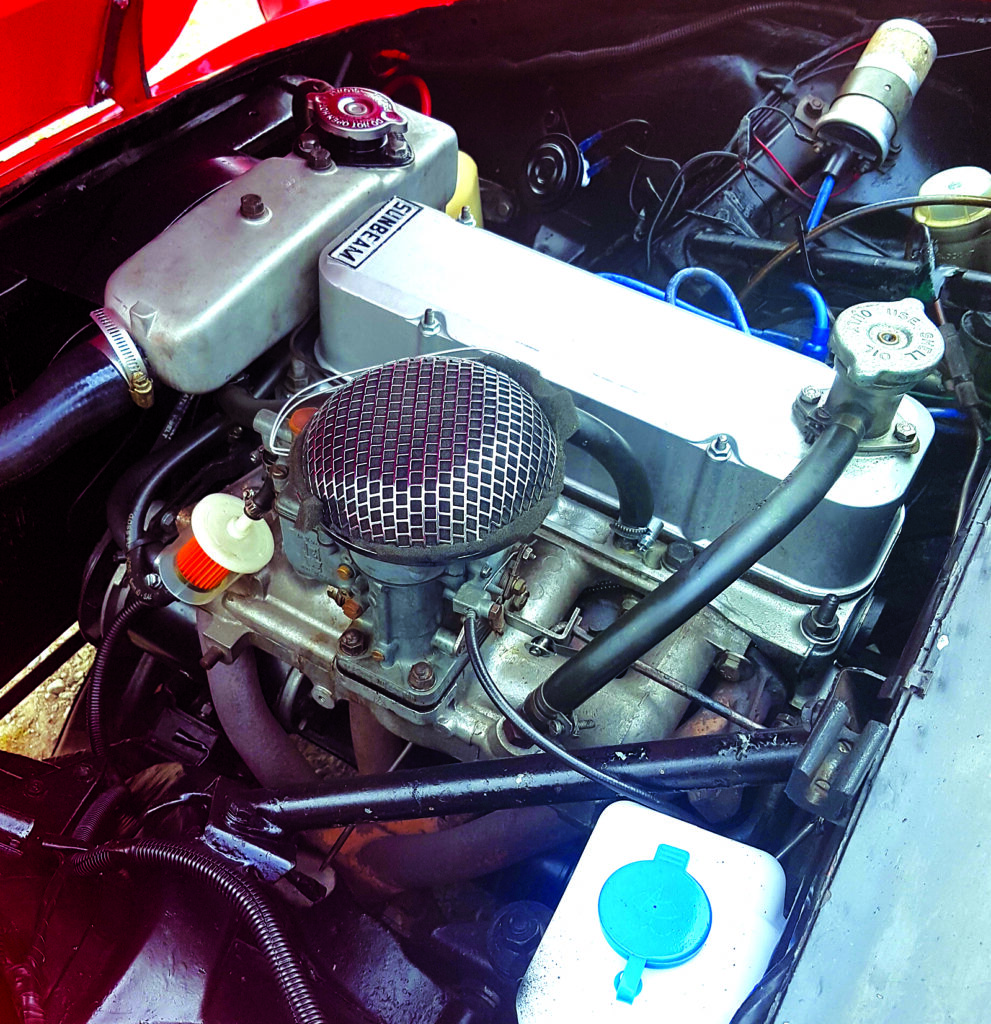

The 1959 Sunbeam Alpine was a one-off concept by British designer Kenneth Howes, who had formerly worked for Loewy studios on Studebaker and Ford. From paper to reality, the car was 100 per cent pure design — a rare thing in the motoring world.

Work began in 1957 and was based on the brief of creating a sports car that included more luxurious features than rivals MGA and the Triumph TR3. The 1959 launch in the French Riviera included a 100km ride up the mountains, finishing with a romantic drive into San Tropez. Enthusiasm from the motoring press was high, and the Alpine was considered an automotive pinnacle for the Rootes Group, which had produced it.

The Alpine’s list of famous drivers and owners is impressive. It was the very first Bond car, driven by Sean Connery in Dr. No; Schwarzenegger drove and crashed one in Commando; and songwriter Paul Simon first heard his song “The Sounds of Silence” on the radio while driving one around New York. It wasn’t the fastest car of its time but the Harrington Alpine, a coach-built coupé version of Sunbeam’s roadster, won the trophy for fuel efficiency at the 1961 Le Mans, beating rivals MGA, Aston Martin, and Porsche.

Heavenly cruising

On a crisp, clear South Island day in September 2019, the barn door opens to reveal my new purchase; I whoop and sigh. The car has a shiny, new, red paint job, the chrome gleams, and she starts on the fifth turn of the key – something that has never changed. This is followed by a comforting growl that lets me know we are on our way. Now, at last, top down, starts the two-day drive from Rangiora to Picton. I’m in heaven.

Nothing compares with the joy of looking across the Alpine’s arched front towards the magnificent Southern Alps up ahead. She moves through the gears smoothly, into a head-turning third gear snarl that echoes off the surrounding hills, sliding into a stately fourth as the car settles into its groove, rolling effortlessly down the sun-filled highway.

A symphony of cutlery

Like all classic car owners I quickly attune to her symphony of quirky sounds. The most unusual and worrying — a sound akin to that of tinkling cutlery — was coming from the left rear wheel. I push the car up over 100K — bang, shudder, clunk, wobble.

Just out of Amberley, the cutlery wheel sounds as if it’s detaching. We pull over, walk around, stare, wiggle things, and tentatively conclude nothing obvious is falling off, but both of us have that feeling that we won’t be soaking in the Hanmer Springs hot pool tonight.

“We’re up against physics and the largely unknown history of a 60-year-old car,” James says rather bluntly.

He’s an adman/creative, I’m a musician/teacher, so neither of us really knows what’s going on mechanically. At least I’m dressed for the occasion, in a smart new tan wool trench coat, brown corduroys, and matching red scarf.

I relaunch and keep to a steady 80kph; the cutlery carries on with its disturbing counter-melody; the open road beckons. There really is no option but to keep driving away from civilisation and any sort of roadside assistance. James convinces me it’s all going to be OK, but I know deep down his day job is selling lies.

Another 10km down the road it happens again, this time even more violently. We’re out of mobile range so I’m just hoping maybe the wheel is a bit loose and we can tighten it. Several people sidle up beside us, always effusive; one couple tells us they had one of those when they got married — we made their day.

“Do you need help?” they ask.

“Nah, we’re OK” – but I’m not entirely OK, as I’m starting to picture a wheel spinning off and bouncing down some uninhabited valley with us left behind amidst the mangled red and chrome wreckage; at least it would be a very pretty-looking crash.

“Always the journey, not the destination,” I remind myself as the engine purr resumes and I pray to the motoring gods for a safe arrival.

Film star looks

Hanmer Springs appears before us. We high five and crank up Miles Davis’s 1959 classic Kind of Blue, and I have my very first inkling that this car needs its very own road-trip soundtrack. As we roll into the hotel car park, someone yells down from the balcony that it looks like a scene from a movie.

“A bloody horror movie,” I mutter under my breath as I smile and give the impression that the car hasn’t given me the merest hint of trouble. Like the movie stars our fellow guests make us out to be, we celebrate the end of the day with red wine and cigars. This in turn inspires ramblings on vehicular mobile artworks and the importance of keeping these designs in the public eye.

Next morning arrives and I’m filled with impending doom. Some kid is down in the car park arguing with his dad about whether the tail lights are old or new. The same dad gives us a smile and says he feels so lucky as he hasn’t seen one of these for years.

“Lucky indeed,” I think, given the touch and go nature of yesterday’s journey; “maybe you’ll be the last human ever to talk to me.”

The engine starts eventually and we drive up to a lookout where a group of tourists are having a roadside cigarette.

“It’s the first Bond car,” says James.

They look wide-eyed and I realise they think this is the Bond car. Suddenly the whole smoking family is leaning against the new paintwork taking photos. This is not helping my nerves at all. I start the engine and floor it across the gravel to coos of appreciation and awe.

The romance of the road

The South Island begins to reveal its unbelievable beauty and clarity of light as we weave and bend past mountain peaks, blue flowing rivers, and bright green forests. Today, while the cutlery wheel continues to chime, there are no morbid rattles, and we are still alive. The road moves beneath us and I start to really understand what a road trip is all about: the warm analogue hum of the engine, the sensory overload of wind and sun, the dreamy pageant of shapes and colour that glides by like a movie set, not a cloud in the sky.

I begin to feel far more optimistic as I hand the wheel over to James. The pressure comes off; he can drive us to our deaths — at least I’ll be enjoying the view. We drive past an airfield just out of Murchison, a glider takes off in perfect synchronicity, bare hills become the endless grape fields of the Marlborough region, and I ponder just how much wine the world must be drinking.

We arrive in Picton at dusk. The car is dropped off at the Bluebridge terminal. We say our goodbyes and head for the Airbnb, which overlooks the Marlborough Sounds, to plan our next epic journey.

Later on that week, back at home in Auckland, I receive the call no one wants to get.

“Ah, we had a bit of a problem getting the car off the transporter; the handbrake failed and we’ve broken the door off – um, it could be worse; it’s really not that bad.”

It is bad, fixable but heartbreaking considering the journey we had gone on to get it here only to have some numbskull back it into a metal strut. There it was, in the middle of a warehouse, looking pummelled and alone. I gave her a silent hug and left it to the insurance company to sort out.

As a musician, I couldn’t stay idle in the four months I waited for the door to be fixed, so I revisited my idea of creating a road-trip soundtrack worthy of the sleek and sexy lines that only a classic car can carry off. Since then, brother James and I have been on countless road trips in the Sunbeam, which we subsequently named ‘Lady P’ after our favourite Thunderbird from the iconic TV show of the ’70s, because of her style and control.

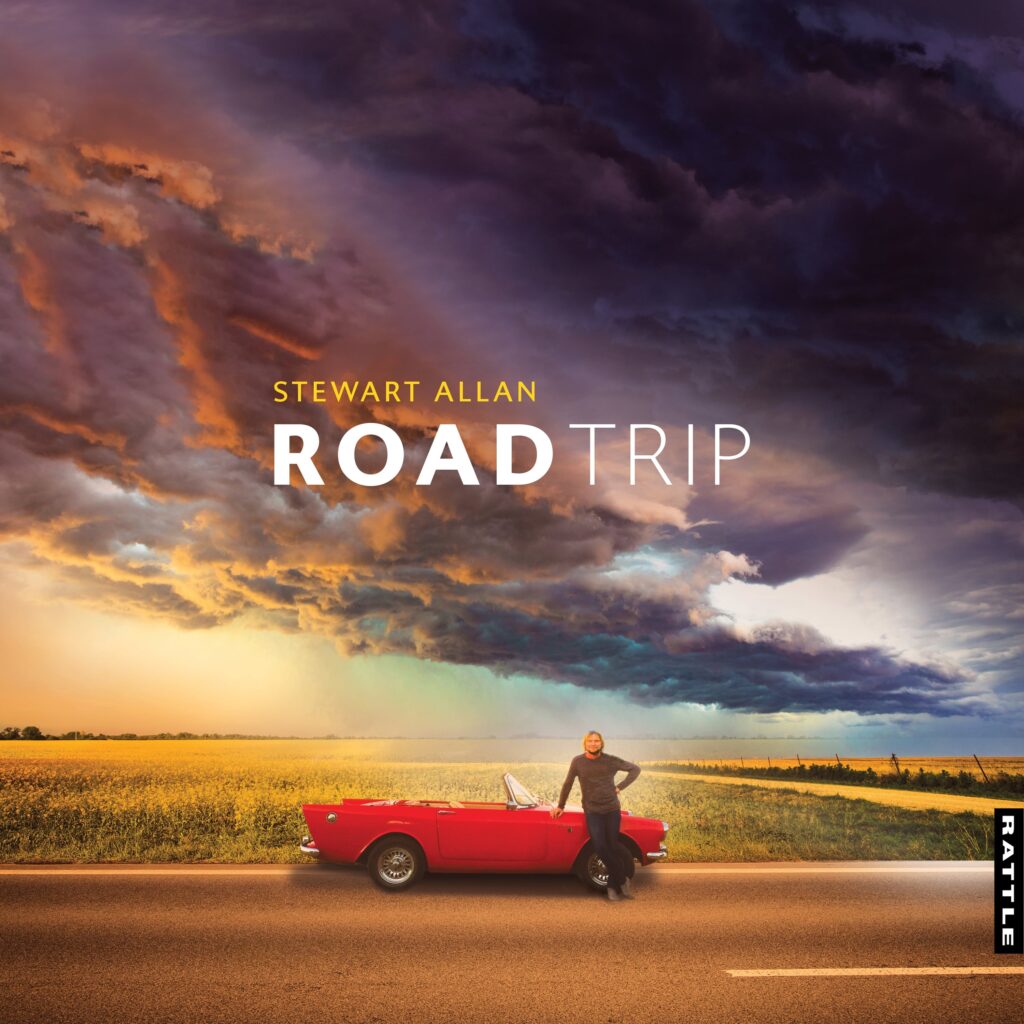

It seems something completely different but never disastrous, always happens on these journeys. On each of these trips a new song emerged, inspired by the car, our friendship, the women and the cars we’ve loved, and the landscape we journeyed through, until a whole album of chill-beat tracks was born. It is, of course, called the only thing it could be: Road Trip.

In the same spirit of brotherhood that our journeys take us on, James and I collaborated over the art and music that Lady P inspired, James gracing the front album art with the 1959 Sunbeam Alpine and the music perfectly evoking that dreamy state she puts me in when I’m behind the wheel, driving through our magnificent country.