Our correspondent has worked up the courage to probe some dark places in his memory that might explain his fear of Fords

By Gerard Richards

The slogan went something like ‘There’s a Ford in your future’. ‘Bugger off!’ were always the words that sprung to my mind.

Ford and I have never really got on in the manner of many of my friends, so I’d say my relationship to the brand was distant. The accelerating blur of passing time has helpfully blanketed memories of a few Ford encounters which I probably wanted to forget but I have to admit, now I look at them, they are re-appearing through the mists of time. What comes to mind more readily, to quote some uncharitable wit, is that the letters Ford could stand for ‘fix or repair daily’. Still, I have to ’fess up, there were several Fords in my past.

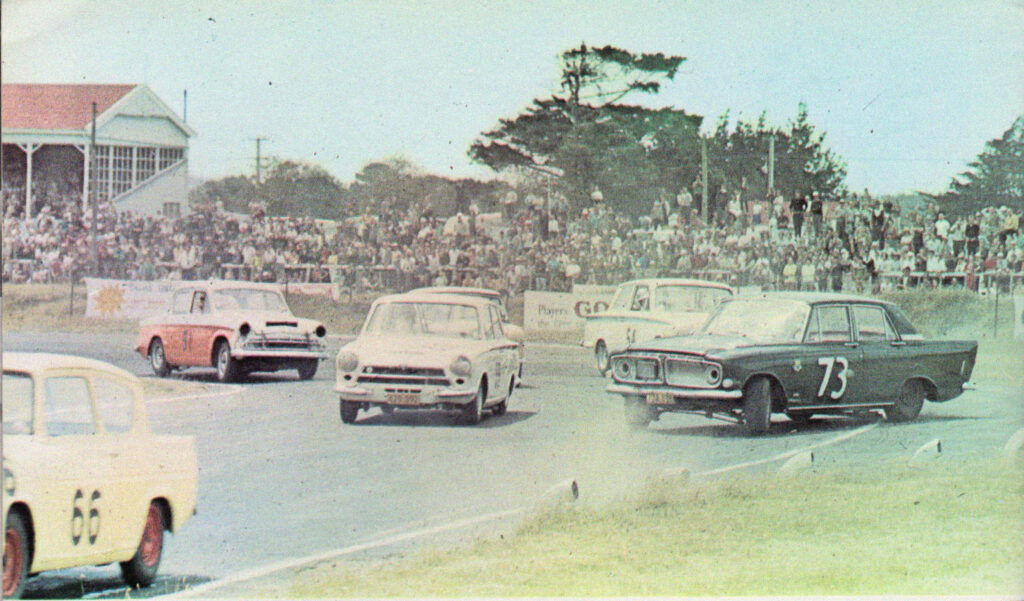

The 1960s ‘Ford Total Performance’ mantra hit motorsport in a big way even in the isolated backwater of Aotearoa. And here, as in most other places, by the end of the decade Ford’s sporty image had hit almost moonshot heights.

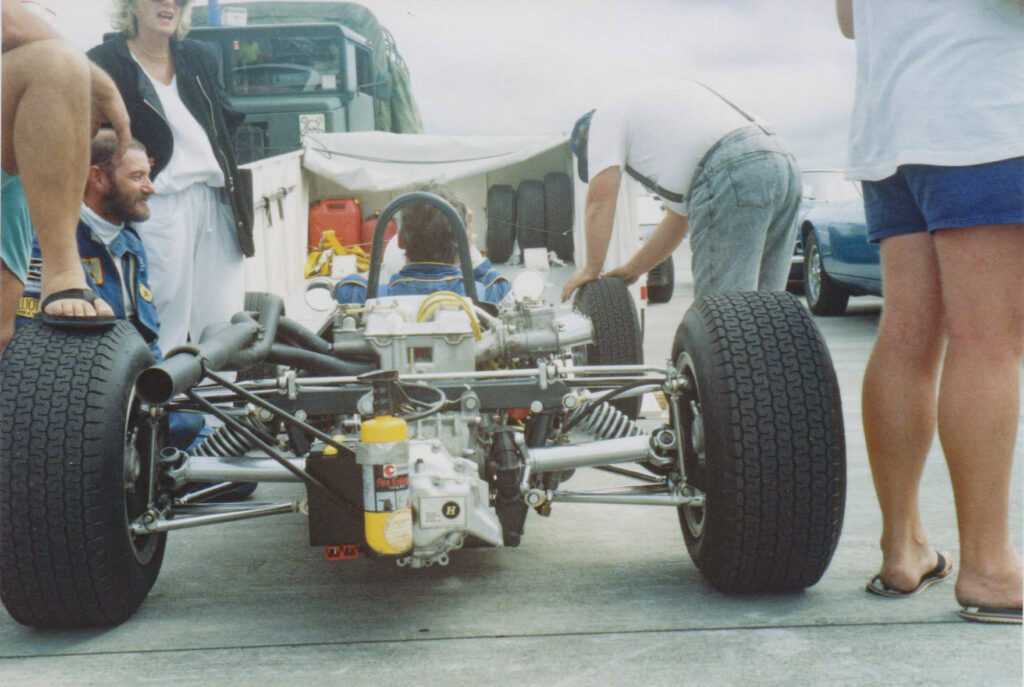

As a young motor racing addict in the Pukekohe paddock, I was hypnotised by the blaze of colour, rakish shapes, and the sound and fury of the scene. The pumping excitement had me almost hyperventilating; this was truly my happy place. Other forms of drug were apparently big back then but I already had mine.

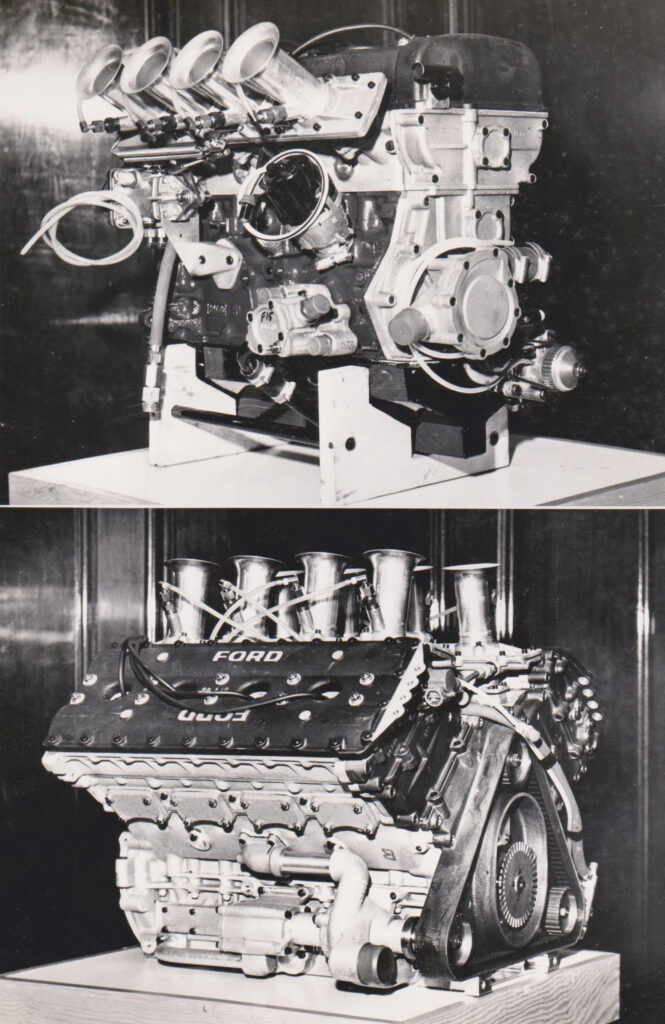

Ford engines and saloon racers were the major players on local circuits and dirt tracks. The powerplants of all these Anglias, Cortinas, and Escorts — not to mention the Brabhams and Lotuses — were all based around the iconic four-cylinder Kent crossflow head and twin cam Ford engine. What a beautifully simple but elegant and highly effective mill when built and tuned properly. With larger valves and higher compression, the engine’s breathing was greatly improved and the power shot up dramatically.

Made in Dagenham

The crossflow Kent engine was a new building block for Ford when it was introduced in 1967. It was the mainstay of Ford four-cylinder engines, until the last units were built in Dagenham in 1983. This engine was a major breakthrough for Ford across their model ranges and gave a substantial increase in power in stock specs. While the bottom end of the motor, which featured innovative oversquare cylinder dimensions, was little different to its predecessors, the big improvement came from layout of the cylinder head.

The refreshed Kent engine’s masterstroke was its crossflow cylinder head with the carburettor ports and manifold on the left side, exhaust on the right, and the combustion chamber was formed almost entirely in the top of the pistons. Which explains why Ford engineers originally knew it as the BIP or ‘bowl in piston’. There was no combustion space at all in the 1.3-litre cylinder head and only a small recess in that of the 1.6-litre unit. Although the 1.6-litre version had the longest stroke of all such Kent engines at 77.62mm, its rock solid five-bearing bottom end also served as the basis for the famous race-winning Ford Cosworth BDA engines — the largest of which were pushed out to 2 litres. Not only was the Kent engine a free revving, virtually unburstable unit in standard form, it was also very tuneable, the crossflow layout making it a simple matter to add bigger carbs and a set of extractors. But that was just the start. An industry quickly sprang up offering high-lift cams, heavy duty valve springs, rocker shafts, conrods, pistons, bolts, one-piece pulleys and double row chains through to new heads with bigger valves.

The gospel according to nimble

Your reasonably skilled club racer could turn out a decently quick car with a modicum of mechanical aptitude. When these machines were bang on, they went like the proverbial scorched cat. They punched way above their weight and were often giant killers, serving out some embarrassing defeats to the heavy muscle car brigade over the years.

Times were changing. High revving, high compression small Ford engines in light cars with better brakes and handling overcame the heavier more cumbersome traditional big saloons. Light and nimble became the gospel. Ford brought about the end of the Jaguar dynasty with their pocket rocket Anglias and the Cortinas.

The list of the legendary frontline drivers who campaigned outstanding small Ford saloon racers throughout these golden summers of the ’60s and ’70s is long. Some of them include: Kerry Grant, Paul Fahey in Lotus Cortinas, Jack Nazer, Dave Simpson in Lotus Anglias, Jim Richards, Paul Fahey, Don Halliday, Bryce Platt in Ford Escorts. I also want to make special mention of my North Shore boyhood hero, Ron Kendall. His wonderfully quick and sweet handling Lotus Twin Cam 100E Anglia speedway saloon, with which he won the 1970-71 NZ saloon title, was a revelation at the time.

In single seaters, Ford twin cam or pushrod version front runners included Graham McRae, Roly Levis, Graeme Lawrence, Andy Buchanan, Ken Smith, Lawrence Brownlee, Graham Baker, and many others. Of course, the Formula Ford category could be included here as well.

All of these men stamped their mark emphatically on the circuit and speedway scene. And let’s not forget the rally fraternity either which burst onto the scene, especially with the advent of the New Zealand International Heatway Rally. In 1973, international stars Hannu Mikkola and Jim Porter of Finland, and New Zealand’s own Mike Marshall and Arthur McWatts, finished first and second respectively in RS1600s.

But in my view, especially with the introduction of the racing Escort, the leading lights that established the prowess of this potent machine were Jim Richards and Paul Fahey in the summer of 1969-70.

So now I am compelled to share with you my own deluded attempt to partake of a slice of this iconic Ford hardware. I embarked on a mission to build a Cosworth modified 1650, sidedraft Weber-inducted Mk2 Escort van. I would be living the Small Hot Ford Dream! At least that was how it looked on paper and in the fevered fantasies in my head. Me building it …? Well that sentence was the only real fabrication going on here. Back then, I was like motoring journalist Eoin Young — barely able to manage an oil change.

The Cosworth van debacle

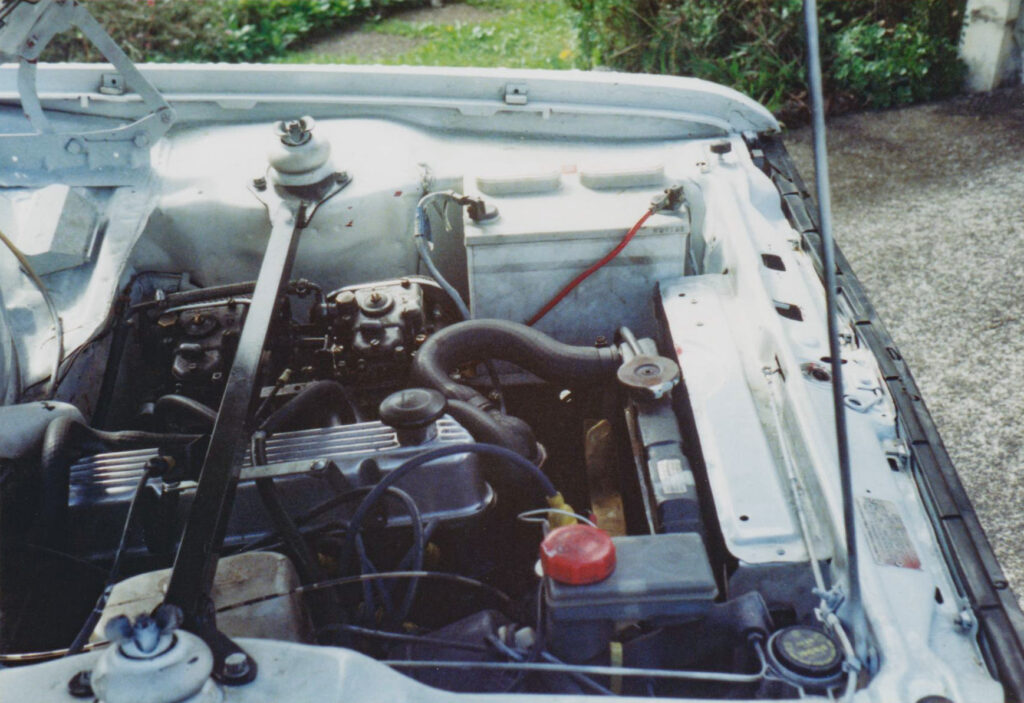

The year was 1987 and I was working at a public library in South Auckland that was frequented by a character who turned out to be a hardcore Lotus nut. As our conversation pressed on into the hot car realm, he detected my weakness for a race bred road machine. Turned out, he just happened to have a 1500 Cortina block, an A3 Cosworth Cam, Cosworth crank, big valve Cosworth head, and a pair of Weber side drafts lying around from a previous (ominously unsuccessful) project. He offered to build me an engine and install it in a 1980 Escort van. Warning bells failed to ring. By this time I was already drooling at the prospect of lining up at the lights and doling out a crushing lesson to any adjacent motorist foolish enough to assume this was just a van. My delusions of zero-to-hero road warriorship were the fatal culprit here — but I’m getting ahead of myself. The crushing of my illusions was safely down the road at this point.

‘What’s not to like?’ summed up my initial excitement, but I was to reflect on my rash enthusiasm in the days ahead. The day finally came when after much expense and many delays, the new machine was delivered to my door. It certainly looked the part. The original, red Escort van was now white with subtle blue stripes, tasteful alloy wheels, little touches like vents in the bonnet, and — sealing the deal — a Momo wheel. Under the hood, in the engine bay where the 1300 had previously looked like a startled stowaway, there was the now classic beefy, bored-out to 1650 Cortina block, a nice finned rocker cover, Weber side drafts, lumpy Cosworth cam and crank, and high pressure oil pump/cooling system and other performance accoutrements.

It really looked the part and I can’t stress the word ‘looked’ enough here … because the sad and tragic lesson for me downstream was the cardinal sin of modifying production cars and not beefing up all the components in the drivetrain. When you elevate the horsepower from a stock 1300 to approximately 160hp with a lumpy race cam, the standard cheap and cheerful transmission hardware — it should be obvious — is not up to the task. Something had to give — and it did, but not before a hideous engine problem emerged. Apparently the piston rings fitted were cast at too low a heat tolerance and started to melt, resulting somehow in copious amounts of oil fanning out into the engine bay.

Somehow despite all this and before the inevitable curtain came down on this ill-judged episode, there were a couple of memorable sorties.

Thirsty Webers

A belt through the rural roads of Franklin out to Manukau Heads went, unbelievably, without a hitch. It was fun but that was the only positive memory I have of it. The day lost some gloss, when we — and I blame my brother who assured me we didn’t need to stop for gas on the way out — miscalculated how much juice those thirsty Webers sucked. We ran perilously low on fuel on the night-time return trip, creeping past country petrol stations which were now, hopes dashed, shut.

The other trip was to Bay Park raceway, towing my brother’s race bike. It got there and back, plus a few side trips, but by then the dark clouds of various terminal factors were starting to gather.

I have only myself to blame for what transpired, as it was all about my delusions of running the classic Ford racing motor in an incognito car. I paid the full price for not thinking it through. As indicated, both the clutch and the gearbox succumbed to the punishment meted out, and the diff wasn’t sounding too flash either. The 1300 went back in, but the damage to the drivetrain was done and I flicked it at the Ellerslie Car Fair for very low bucks. A salutary lesson and the sting in the tale is that somehow, after the transplant I never managed to get the Cosworth components and Webers back either. My friend from the library had swiftly moved them on. That still gives me cause to wince. A total disaster. That was my last Ford, and to be sure that has probably and unfairly tainted my view of Ford’s wares.

But there were other Ford encounters before that and as the mists continue to clear I’ll probe them for more signs of life in the part two of this article.